Introduction: When Survival Is Used Against You

Survivors of workplace sexual harassment often face a cruel paradox: the very behaviors they adopt to survive abuse—composure, professionalism, even gratitude—are later used to discredit them. Legal systems and institutional investigators too often expect survivors to act like “perfect victims”—angry, immediate, and emotionally raw. But in reality, trauma usually looks like silence, overachievement, or even friendliness toward an abuser. This blog explores the psychological phenomenon of toxic resilience—how survivors normalize abuse to endure hostile environments—and how employers weaponize those survival strategies to undermine credibility, delay accountability, and minimize liability. It makes the case for a trauma-informed legal and policy response by drawing on trauma research, federal and state legal frameworks, and real-world institutional patterns. Survivors don’t fail to resist. They succeed in surviving systems stacked against them. It’s time the law caught up.

I. The Myth of the “Perfect Victim”

Despite decades of civil rights enforcement, internal policies, and public discourse, one myth remains deeply embedded in how sexual harassment cases are judged—legally, administratively, and culturally: the myth of the “perfect victim.” This myth tells us that real victims speak up immediately, react emotionally, and distance themselves entirely from their harassers. But in reality, many survivors respond in ways that appear contradictory—remaining polite, productive, and even friendly toward those who harmed them. The legal system often punishes these coping mechanisms, interpreting them not as survival strategies but as signs of consent or fabrication.

This expectation of idealized victim behavior is deeply flawed. It fails to account for how trauma manifests in professional settings, particularly where job security, immigration status, career advancement, or personal safety are at stake. Survivors may not object in the moment, not because they consented, but because they fear retaliation. They may continue engaging with their harasser because they feel trapped by institutional power structures or fear being ostracized. They may laugh off comments or send conciliatory messages to de-escalate tension—not to invite more abuse.

Courts, administrative bodies, and internal investigators frequently misinterpret these behaviors. In doing so, they reinforce the dangerous assumption that victims must behave a certain way to be credible. That assumption is not only outdated—it is incompatible with both trauma psychology and workplace realities. The harm is compounded when institutions leverage this myth to discredit survivors, frame their behavior as inconsistent, and ultimately avoid accountability.

Understanding the myth of the perfect victim is the first step toward dismantling the structural and legal barriers that continue to retraumatize those who endure workplace sexual harassment. Survivors don’t need to be perfect. They need to be protected. And the law must evolve to meet them where they are—in the full complexity of their lived reality.

II. Understanding Toxic Resilience: A Psychological Primer

Toxic resilience is a survival strategy born of necessity. It refers to how individuals adapt to abusive or coercive environments by minimizing their trauma responses to function, endure, or stay employed. In the context of workplace sexual harassment, this adaptation often presents as composure, compliance, or even gratitude toward a perpetrator. Far from indicating consent or comfort, these behaviors are frequently symptoms of a more profound psychological calculation: if I act normal, maybe I’ll be safe.

Survivors may overachieve to protect their reputation, suppress emotional reactions to avoid being labeled “unprofessional,” or continue cordial communication with their harasser to maintain access to funding, recommendations, or professional networks. They may rationalize the abuse, dissociate from it, or minimize it entirely to survive within institutions that have historically failed to protect them. These behaviors are not indicators of falsehood—they are evidence of trauma-informed adaptation.

Trauma expert Dr. Judith Herman, in Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence—from Domestic Abuse to Political Terror (1992), explains how prolonged abuse can fundamentally alter a person’s sense of agency, producing “a changed relationship to the body, to the self, and others” (p. 93). In coercive environments, victims often preserve stability by appearing cooperative or compliant, even when the behavior is unwanted or harmful. Resistance may feel dangerous, while outward adaptation offers the only available control.

Similarly, Dr. Bessel van der Kolk, in The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma (2014), outlines how trauma rewires the brain. He explains that trauma activates the amygdala—the brain’s fear center—while impairing the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, which govern reasoning and memory. As van der Kolk writes, “The imprint of trauma doesn’t ‘sit’ in the verbal, understanding, part of the brain, but in much deeper regions—amygdala, hippocampus, hypothalamus, brain stem—which are only marginally affected by thinking and cognition” (p. 43). As a result, survivors may appear flat, disengaged, or even inappropriately composed—not because they were unaffected, but because their bodies and minds were working to survive.

Pete Walker, in his 2013 book Complex PTSD: From Surviving to Thriving, identifies the “fawn response” as a fourth trauma adaptation, alongside fight, flight, and freeze. The fawn response involves appeasing perceived threats by accommodating them—submerging one’s own needs and boundaries to maintain safety. As Walker describes, “Fawn types seek safety by merging with the wishes, needs, and demands of others. They act as if they believe the price of admission to any relationship is the forfeiture of all their needs, rights, preferences, and boundaries” (p. 13). In workplace settings, this may look like over-cooperation, emotional caretaking, or expressions of loyalty toward an abuser—not because the survivor welcomes the behavior, but because they are attempting to reduce harm by appearing agreeable.

This pattern doesn’t occur in a vacuum. It develops within institutions that subtly or overtly signal that reporting misconduct will result in retaliation, disbelief, or career derailment. Dr. Jennifer Freyd, in her work on institutional betrayal, explains that when trusted institutions fail to respond adequately to misconduct, they not only compound the trauma but also train survivors to remain silent. In her words, “Institutional betrayal is an added layer of harm that can exacerbate the impact of the original trauma and make recovery more difficult” (Freyd, 2013, Journal of Trauma & Dissociation). In such settings, silence becomes a learned behavior—not because there is no harm, but because the survivor knows that naming it might lead to more significant damage.

Consider a junior analyst at a private financial firm. She receives inappropriate comments daily from a senior partner who controls her project assignments. Rather than risk her future, she works harder, avoids conflict, and even compliments him in emails. When she later reported the misconduct, HR pointed to her “positive relationship” with the harasser as proof nothing was wrong. What they fail to see—or willfully ignore—is that her professionalism was a shield, not consent. Her resilience was how she survived, not proof she wasn’t harmed.

These trauma responses, while psychologically sound, are legally misunderstood. Under Title VII, the NYSHRL, and the NYCHRL, the legal standard is whether the conduct was unwelcome and altered the terms, conditions, or privileges of employment. Yet, courts and employers often substitute this legal test with informal tone, timing, or demeanor judgments. As a result, survivors who demonstrate high-functioning coping mechanisms are excluded from protection, while only those who break down visibly or immediately are deemed “credible.” This is not trauma-informed justice—it is legal formalism, masking systemic failure.

Understanding toxic resilience is critical for anyone investigating, adjudicating, or litigating workplace sexual harassment. It challenges the legal system’s obsession with demeanor and exposes the deep gap between survivors’ reality and institutional response. These behaviors are not evidence of fabrication. They prove what it takes to stay employed in systems that continue to reward silence and punish resistance.

🔷 SIDEBAR: These Protections Apply to You—No Matter Where You Work

Sexual harassment laws apply to nearly all workplaces, not just corporate offices or government agencies. Under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, the New York State Human Rights Law (NYSHRL), and the New York City Human Rights Law (NYCHRL), legal protections extend to:

Employees, contractors, interns, temps, and volunteers. Workers in public, private, nonprofit, and gig economy sectors. Institutions large and small—including those with only one employee under NYS law.

If you’ve been harassed or retaliated against at work, you may have legal remedies regardless of your job title, employer type, or industry. Do not let anyone—whether in Human Resources, management, or legal—tell you otherwise.

III. Legal Disconnect: When the System Punishes Survival

Despite advances in civil rights jurisprudence, the legal system continues to reward a narrow and outdated understanding of how victims are “supposed” to behave. It remains more comfortable with narratives that feature immediate outrage, emotional breakdowns, or documented resistance than with the far more common reality: victims who say nothing, smile politely, and continue to function in high-performance roles long after the abuse begins. These expectations create a dangerous legal disconnect—one that punishes survivors not for their harm but for how well they adapted to it.

Courts, arbitrators, and internal investigators often dismiss harassment complaints based on perceived inconsistencies in the survivor’s behavior. Judges may point to a lack of contemporaneous reporting. Employers may argue that “she never objected” or that “he continued to engage with his supervisor without issue.” However, these standards ignore the well-documented neurobiological effects of trauma on behavior, memory, and communication.

In The Neurobiology of Sexual Assault, trauma researcher Dr. Rebecca Campbell explains that the brain’s response to fear and violation is not limited to fight or flight—it often includes involuntary responses like freezing, collapsing, or dissociating. According to her findings, trauma suppresses activity in the prefrontal cortex—the brain area responsible for reasoning, speech, and planning—while activating the amygdala and brain stem, which control instinctual survival responses. As a result, survivors may appear calm, numb, disoriented, or emotionally flat—not because the incident wasn’t traumatic, but because their brain has gone into survival mode. These reactions are neurobiological—not behavioral choices—and reflect how trauma impairs verbal expression and executive function in the moment.

Dr. Steven M. Southwick and colleagues have documented how trauma disrupts memory encoding and retrieval, particularly in survivors of chronic interpersonal abuse. In their work on resilience and post-traumatic stress, they explain that trauma memories are often stored as fragmented, sensory, or emotional impressions—rather than as structured, chronological narratives. This neurobiological reality makes immediate and consistent disclosure difficult, especially when a survivor must also navigate the fear of retaliation, institutional disbelief, or professional ruin. As Southwick and Charney note in Resilience: The Science of Mastering Life’s Greatest Challenges, trauma can impair the ability to “organize thoughts, communicate clearly, and accurately recall what happened”—effects frequently misunderstood in legal and investigative settings.

The law, however, still asks the wrong questions. It wants to know why the survivor didn’t report sooner. Why did they send a friendly email? Why didn’t they file a complaint until their performance began to suffer? Under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the legal standard is whether the conduct was unwelcome and altered the terms, conditions, or privileges of employment. But in practice, that standard is often replaced with subjective assumptions about credibility based on demeanor, delay, or emotionality.

This is especially dangerous in cases involving toxic resilience, where survivors have learned to survive by appearing unaffected. In such cases, silence is treated as acquiescence, politeness is cast as proof of consent, and composure is mistaken for fabrication. Employers and courts often rely on this logic to deny claims, minimize liability, or discipline complainants who finally speak out after months or years of coping internally.

The result is a double injustice. Survivors are not only harmed by the original misconduct—they are later disbelieved because they responded in a way that prioritized survival over disclosure. And the institutions that benefit from their silence continue to weaponize it, shielding themselves from accountability with the false logic that trauma leaves no room for professionalism.

The Legal Catch-22

If you speak up, you’re unstable. If you stay silent, you’re complicit. If you thank your boss, it was consensual. If you act composed, you’re lying. If you show fear, you’re hysterical. The law says survivors must act “reasonably,” but trauma suspends reason. And courts too often punish survivors for surviving in the only way the system allows.

This legal disconnect fails to capture the survivor experience—it entrenches the very systems that force victims to choose between safety and credibility. To close the gap, our legal standards must evolve—not only to reflect what trauma experts have long known but also to stop rewarding the very silence that institutions have taught survivors to perform.

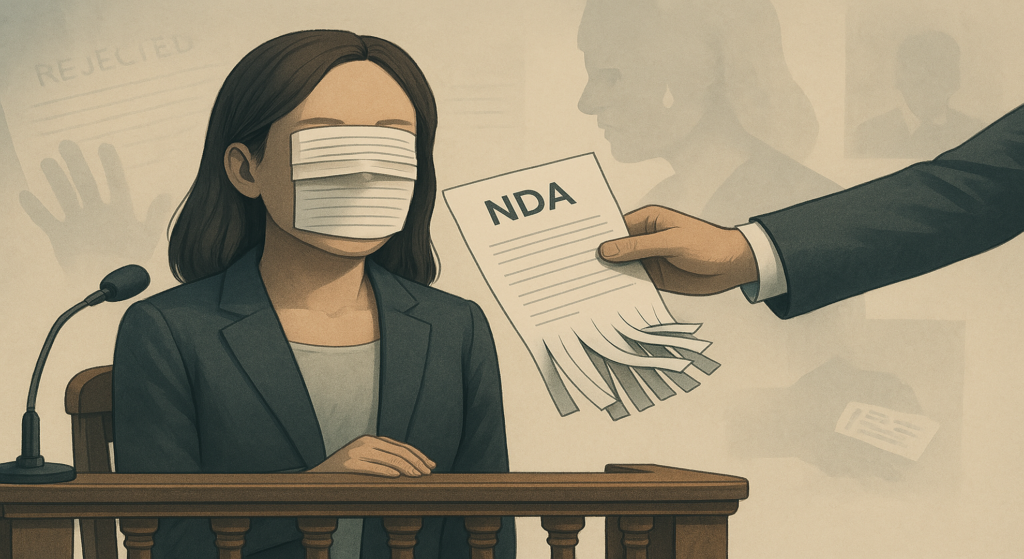

IV. Institutional Weaponization: How Employers Use Resilience Against Survivors

In workplaces across sectors, employers increasingly exploit trauma-adapted behaviors—such as composure, professionalism, or even gratitude—as a legal and reputational shield. The same survival strategies that help victims navigate hostile environments are later repackaged as evidence that misconduct never occurred. Politeness becomes consent. Silence becomes fabrication. Delayed reporting becomes proof of unreliability. These distortions are not incidental—they are part of a deliberate institutional playbook designed to contain liability and discredit survivors without ever addressing the harm.

When a survivor sends a polite email to a harasser, that message is submitted as an exhibit. When they continue to work under the same supervisor, their endurance is cited as evidence that the relationship was benign. If a promotion follows months of abuse, employers point to that advancement as proof that no retaliation or discrimination could have occurred. However, these arguments ignore the fundamental realities of power and fear in the workplace. Many survivors remain productive because they are economically dependent on the job, or because they believe—even correctly—that reporting will result in retaliation, blacklisting, or being driven out. Their performance is not proof of safety. It is proof of strategy.

This institutional misreading aligns with what trauma experts describe as the fawn response—an appeasement instinct in which survivors accommodate perceived threats to avoid triggering further harm. Pete Walker, in Complex PTSD: From Surviving to Thriving, explains that individuals in this state “seek safety by merging with the wishes, needs, and demands of others” and may believe “that the price of admission to any relationship is the forfeiture of all their needs, rights, preferences, and boundaries” (p. 13). In employment, this might mean thanking an abusive supervisor, laughing off inappropriate comments, or continuing to show up daily—not because the conduct was welcome, but because appearing unfazed is often the only protection available.

Rather than understand these responses as protective, employers and their internal investigators often treat them as inconsistencies. Institutions turn survivor resilience into ammunition: she smiled, so she must have been fine; he didn’t file a complaint, so it must not have mattered. These narratives erase the coercive context. They rely on the absence of visible suffering to avoid accountability while ignoring the profound psychological and economic calculus that drives survivors to adapt.

As Dr. Jennifer Freyd explains in her work on institutional betrayal, when institutions fail to prevent or adequately respond to misconduct, they don’t just fail—they become part of the harm. In her 2013 study published in the Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, Freyd found that betrayal by trusted systems intensifies trauma and reinforces the very silence that predators and institutions rely on. That silence then becomes institutional cover: “She never said anything.” “He smiled in the meeting.” “She didn’t object.”

These justifications are surface-level denials of a more profound truth—that many survivors remain quiet not because they were unharmed but because they understand precisely what would happen if they speak up. And too often, they were right. Speaking out leads to disbelief, retaliation, stalled careers, or forced exits. Remaining silent, adaptable, and composed is not weakness but survival. But when that survival is later used against them, survivors are forced to pay for their professionalism with their credibility.

This is not a training gap. It is a feature of institutional risk management. When trauma-adapted behavior is reinterpreted as fabrication, institutions avoid investigations, minimize legal exposure, and protect reputational interests. Doing so creates a workplace culture where silence is incentivized, trust is corroded, and misconduct is quietly recast as misunderstanding or consent. It is not the original misconduct alone that drives survivors out—it is the second betrayal, when the institution turns their coping into a cover story.

V. The Culture of Survival: Why Normalization Happens

Normalization is not a failure of courage—it is a survival strategy shaped by threat, power imbalance, and institutional silence. Survivors of workplace harassment and abuse often make calculated decisions to remain quiet, cooperative, or high-performing in environments that have signaled, either directly or indirectly, that reporting misconduct will result in professional or personal harm.

Many survivors remain silent to preserve their jobs, access to benefits, or future advancement. Others fear retaliation, blacklisting, or professional isolation—especially when the perpetrator holds sway over references, funding, or promotion. For immigrant workers, the stakes can include visa sponsorship or deportation. In academia, research settings, and civil service roles, entire careers can hinge on a single influential figure. Silence becomes strategic. Resilience becomes the currency of survival.

These choices are neither passive nor irrational. They are shaped by environments that punish disclosure and reward endurance. Dr. Jennifer Freyd’s Institutional Betrayal Theory explains how trust in leadership, HR, EEO, or compliance offices is eroded by repeated failures to intervene or investigate appropriately. When survivors observe that prior complaints were ignored, covered up, or met with retaliation, they conclude—rationally—that coming forward is more dangerous than staying quiet. The institution’s betrayal is not just a failure of protection. It is a message: protect yourself because no one else will.

The result is a workplace culture where trauma is internalized, misconduct is normalized, and silence is rewarded. Over time, this dynamic forces survivors to choose between career and dignity—between professional safety and personal justice. Many lose both.

To understand toxic resilience, the law must examine what survivors did and what systems taught them to do. Normalization is not a sign that harm didn’t occur—evidence that it was too costly to name.

VI. Legal Reforms and Advocacy Solutions

Institutional betrayal is the enabling condition if toxic resilience is the survival response. Together, they reveal a legal and cultural framework that punishes silence and performance more than it punishes abuse. That framework must be dismantled not only through individual lawsuits but also through systemic policy reform. Survivors deserve more than procedural boxes to check or hostile internal investigations—they need structural protections designed around the realities of trauma, coercion, and power.

Too many current legal and institutional standards rely on outdated assumptions about how victims should behave. They penalize delays, reward composure with disbelief, and treat deference as consent. Worse, internal processes are often controlled by actors whose primary loyalty is to the institution, not the truth. Human Resources, legal departments, and compliance offices are tasked with minimizing liability, not validating trauma. Without independent oversight, trauma-informed protocols, and enforceable transparency, survivors remain trapped in a system built to silence them.

What follows is not a wish list. It is a framework for survivor-centered institutional accountability—a checklist designed to shift credibility determinations away from trauma stereotypes and toward structural fairness.

Survivor-Centered Policy Checklist:

✅ Prohibit dismissal of complaints based on delayed reporting, neutral demeanor, or perceived “inconsistencies” in survivor behavior. Require decision-makers to be trained on trauma adaptation, including dissociation, appeasement, and strategic compliance.

✅ Mandate trauma-informed training for all internal investigators, arbitrators, and adjudicators involved in harassment claims. Training must include the neurobiology of trauma, institutional betrayal theory, and bias recognition.

✅ Require survivors to receive outcome disclosures—including whether the allegations were substantiated and what remedial action was taken—rather than being left in the dark under vague confidentiality claims.

✅ Ban using emails, smiles, “thank you” messages, or professional achievements as automatic evidence of consent or fabrication. Institutions must consider context, power dynamics, and behavior patterns, not isolated communications.

✅ Establish independent ombuds programs or public-interest monitors in high-risk institutions—particularly law enforcement, higher education, and public agencies—with authority to audit complaints, flag retaliation, and recommend discipline.

✅ Expand anti-retaliation protections under state and local law to cover all reporting methods—verbal, informal, anonymous—and impose penalties for overt and subtle retaliation, including isolation, micromanagement, or manufactured performance issues.

This checklist is not exhaustive, but it is foundational. The goal is to improve internal compliance and shift power toward truth, safety, and equity. Institutions must no longer be allowed to control both the narrative and the process. Survivors must be able to come forward without being retraumatized by the very systems that claim to protect them.

Real accountability begins with structural reform. If institutions cannot be trusted to investigate themselves, the law must ensure they are investigated from the outside.

VII. Federal Legislative Tie-In: From Trauma to Transparency

Toxic resilience is not only a psychological adaptation—it is a systemic symptom of legal opacity. Survivors remain silent not because the harm is unclear but because the path to accountability is blocked by nondisclosure agreements, buried investigations, and the institutional pretense that misconduct ends with an apology or a resignation. As it currently functions, the legal system incentivizes silence and protects reputational risk over human safety. Trauma-informed policy must be paired with enforceable federal and state transparency mandates to break that cycle.

The truth is that most institutional harassment and retaliation never become public. Even when cases settle, the underlying allegations are rarely disclosed. Confidential agreements protect not only individual perpetrators but also the institutional failures that enabled them. Patterns of abuse—particularly in large employers, public agencies, and law enforcement—remain invisible until the damage is irreversible. That invisibility is by design.

This is why survivor justice cannot rely solely on internal reform. We need legislation that forces public disclosure of civil rights violations, harassment settlements, and repeat-offender patterns. We need federal enforcement frameworks that treat sexual harassment and retaliation not as isolated personnel issues but as systemic civil rights violations with profound public interest implications.

Component 2: The Civil Rights Liability Disclosure framework we have proposed is modeled on the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s EEO-1 demographic reporting tool—but with one critical addition: mandated disclosure of the scope, scale, and financial cost of discrimination and harassment settlements. This reporting mechanism would apply to all public employers and private employers over a defined size threshold and would:

Require annual reporting of all settlements involving discrimination, harassment, or retaliation, disaggregated by protected class.

Include settlement amounts, type of conduct alleged, and institutional role of the accused (e.g., supervisor, department head, executive)

Identify repeat offenders or high-risk agencies, departments, or units

Be publicly accessible, with privacy safeguards for survivors

Allow the EEOC and state agencies to initiate pattern-and-practice investigations based on reporting anomalies

These reforms are not aspirational—they are essential. Without visibility, there is no accountability. Without accountability, there is no deterrence. Without deterrence, institutions have no reason to stop weaponizing survivor behavior to protect their own.

Alongside this federal framework, we also support:

A ban on non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) in cases involving sexual harassment, discrimination, or retaliation, unless requested by the survivor

Funding for independent monitors in public institutions with a history of credible claims

Public audit requirements for law enforcement agencies, schools, and health systems receiving federal funds

Civil penalties for repeat employer noncompliance with EEOC or state agency remedial orders

The legislative goal is simple: shift the risk from survivors to systems. Stop treating disclosure as a liability and start treating it as an instrument of public safety, workforce equity, and legal enforcement.

Until institutional secrecy is eliminated, survivors will continue to adapt in silence. Until settlement data is made public, no one—not regulators, lawmakers, or the courts—will fully grasp the extent of institutional complicity. And until employers are forced to account for the harm they pay to hide, they will keep doing what they’ve always done: deny, delay, and deflect.

The law can either protect institutions from survivors or protect survivors from institutions. It cannot do both.

VIII. The Crimes Behind the Policies: When Institutions Misclassify Felony Conduct

Too often, what institutions classify as “misconduct” is, in fact, a felony. Rape. Sexual abuse. Forcible touching. These are not HR violations but criminal acts under New York law. Yet time and again, employers treat these offenses as mere breaches of policy. They substitute internal reviews for criminal referrals, euphemize assault as “inappropriate behavior,” and quietly negotiate settlements while perpetrators remain in positions of power. This is not a procedural failure. It is a legal misclassification with real consequences—for survivors, for public safety, and institutional legitimacy.

Under New York Penal Law, sexual offenses are clearly defined. Rape in the Third Degree (PL § 130.25) includes sexual intercourse without consent due to coercion or abuse of authority. Criminal Sexual Act (PL § 130.40) criminalizes coerced oral or anal sexual conduct. Sexual Abuse in the Second and Third Degrees (PL §§ 130.55, 130.60) covers non-consensual sexual contact. Forcible Touching (PL § 130.52) criminalizes intentional, unwanted physical contact for sexual gratification. These offenses do not cease to be crimes because they happen in a professional setting. They do not become “private matters” because the perpetrator is a colleague or supervisor. And they do not stop being prosecutable simply because an employer chooses to resolve them internally.

What makes this institutional minimization even more egregious is the legal framework that allows for both civil and criminal accountability. New York courts have repeatedly held that off-site, after-hours, or off-duty conduct can still result in employer liability when it arises “in connection with employment.” Supervisors who assault subordinates at conferences, company parties, or on business trips are not acting outside the bounds of law—they are committing workplace-related crimes. Yet, employers continue to act as if location determines legality. They treat jurisdiction as discretion. And in doing so, they not only fail survivors—they enable repeat offenses.

The most severe cases involve coercion through power. Under Penal Law § 130.00(8), “forcible compulsion” includes physical force and express or implied threats that place a person in fear of immediate harm. In employment, that harm may be economic—job loss, funding, immigration sponsorship, or professional reputation. When a supervisor uses their position to extract sex through threat or manipulation, the act may constitute First-Degree Rape (§ 130.35), Criminal Sexual Act (§ 130.50), or Aggravated Sexual Abuse (§ 130.66–70). These are Class B felonies. Yet most institutions treat them as poor judgment, boundary violations, or inappropriate relationships.

This legal misclassification has devastating ripple effects. It shields perpetrators from prosecution. It silences survivors who are told to trust internal grievance processes. It deprives prosecutors and civil rights agencies of access to key evidence. And it tells every employee watching that abuse may be tolerated, rebranded, or quietly paid off—as long as it serves the institution’s bottom line.

In law enforcement agencies, this dynamic is particularly corrosive. Internal Affairs units frequently investigate criminal acts like sexual assault without ever notifying outside prosecutors. In academia, Title IX offices routinely process felony-level abuse through administrative panels. In corporate America, legal departments negotiate NDAs to contain reputational fallout while making no criminal referral. In each case, the institution claims compliance. But what it achieves is concealment.

No amount of internal training or cultural change will correct this if institutions are not legally compelled to treat criminal conduct as such. It is time for mandatory external referral requirements, independent investigatory mandates, and civil penalties for employers knowingly misclassifying or concealing felony conduct. Prosecutorial discretion cannot be circumvented by private policy.

Justice does not end at the HR department. Nor does the law. When rape is treated as a personnel issue and coercion is rebranded as a misunderstanding, institutions not only violate their duty of care—they may be complicit in obstruction. It is time to call these acts what they are and to treat the institutions that conceal them accordingly.

IX. Conclusion: Resilience Isn’t Proof of Consent—It’s Proof of Survival

Toxic resilience is not a contradiction but the most apparent evidence of institutional failure. When survivors appear calm, composed, or even grateful toward the people who harmed them, they are not validating abuse—they are surviving it. They navigate systems that punish disruption, discredit emotion, and reward silence. And when those same systems later point to professionalism as proof that no harm occurred, they are not seeking truth—they are seeking cover.

Resilience in the face of workplace harassment is often mistaken for consent. Silence is framed as complicity. Composure is read as fabrication. But the reality is more straightforward and far more damning: survivors are adapting to an environment where speaking out often leads to retaliation, unemployment, or erasure. They are calculating the odds and making the only rational decision the system leaves them—to stay quiet, perform well, and hope the abuse stops before it ruins them.

Legal frameworks, internal investigations, and cultural expectations have failed to recognize this dynamic. They continue to rely on assumptions about how “real” victims behave while ignoring decades of trauma research and thousands of lived experiences that prove otherwise. They ask the wrong questions, apply the wrong standards, and punish the wrong people. And when institutions mistake survival for submission, they perpetuate harm and legitimize it.

It is not enough to reform policies or train investigators. We must overhaul the legal logic that treats composure as evidence against survivors. We must demand transparency from institutions that profit from silence. We must recognize that survival under coercion is not compliance—it is resistance in its most professional form.

Justice must begin with believing that trauma does not always look like harm. Sometimes, it looks like showing up early, meeting deadlines, sending thank-you emails, getting promoted, staying quiet, and looking stable. These are not signs that nothing happened. They are signs that something did—and that the system made honesty too dangerous to risk.

Resilience is not weakness, consent, or the absence of trauma. It is what happens when people learn to endure what should never have been allowed to occur. The legal system must stop punishing survivors for doing what it trained them to do: survive.

Silence isn’t consent. Strength isn’t submission. And professionalism should never be a weapon.