Section 1: A Crisis Hidden in Plain Sight

Every year, law enforcement agencies across the United States quietly spend hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars to settle lawsuits alleging sexual harassment, gender discrimination, retaliation, and other civil rights violations. These settlements often resolve serious claims brought by officers, detectives, administrative staff, and civilians who suffered abuse at the hands of their colleagues or supervisors—many of whom remain on the job. And yet, there is no national reporting requirement, no statewide publication mandate, no central database where the public can track who is being paid off, how much, and why.

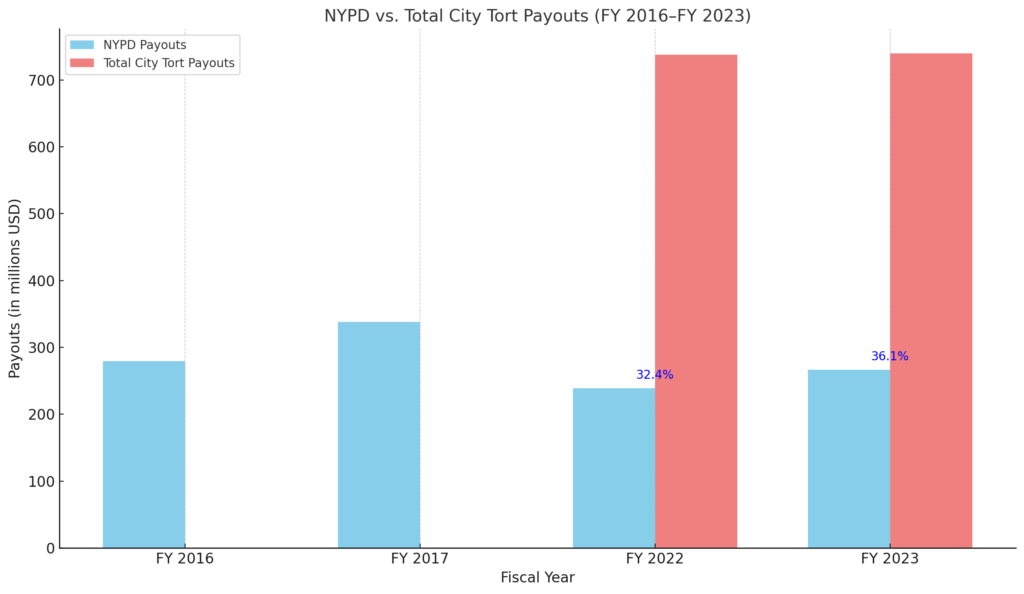

This is especially true in New York City, where the NYPD operates under a veil of secrecy despite being one of the most frequently sued police departments in the country. Between FY 2016 and FY 2023, New York City likely paid out well over $1.9 billion in tort settlements, based on annual Comptroller reports, with the NYPD consistently accounting for approximately one-third of those payouts.

Notes:

FY 2016: The NYPD’s settlement payouts totaled $279.7 million. NYC Comptroller’s Office

FY 2017: The NYPD’s settlement payouts reached a high of $338.2 million. NYC Comptroller’s Office

FY 2022: The NYPD’s settlement payouts were $239.1 million, accounting for approximately 32.4% of the City’s total tort payouts of $737.8 million. NYC Comptroller’s Office

FY 2023: The NYPD’s settlement payouts increased to $266.7 million, representing about 36.1% of the City’s total tort payouts of $739.6 million.

Please note that comprehensive data for the total City tort payouts and the NYPD’s share for FY 2016 and FY 2017 are not readily available in the provided sources. For a complete analysis, consulting the full Comptroller’s Annual Claims Reports for those specific years would be beneficial.

While the raw numbers are staggering, the real problem is this: we don’t know how much of that money went to resolve cases of discrimination, harassment, or retaliation. The data is not broken down. The identities and ranks of repeat offenders are not disclosed. The circumstances of the abuse remain shielded from public scrutiny.

When allegations emerge—like those made by Captain Gabrielle Walls against NYPD Chief of Department Jeffrey Maddrey or Shemalisca Vasquez, Ann Cardenas, and Captain Sharon Balli—the public only hears fragments, what these stories reveal, however, is a pattern: women, men and LGBTQ+ employees come forward with credible claims, face internal retaliation or ostracization, and then the City quietly settles, without acknowledging wrongdoing or disciplining the perpetrators. Often, these payouts include non-disparagement clauses or are routed through legal strategies that insulate the institution from meaningful change.

The problem is not just the misconduct—it’s the concealment. And that concealment is facilitated by the absence of a legal mandate to disclose settlement data tied to discrimination and harassment within public institutions. There are more transparency requirements for a slip-and-fall lawsuit on city property than for a sexual assault settlement involving a uniformed NYPD officer.

This lack of accountability has consequences far beyond individual cases. It erodes trust in the department, burdens taxpayers with the costs of systemic failure, allows patterns of abuse to fester unchecked, and creates a chilling effect within the workforce, where potential whistleblowers—especially those from marginalized backgrounds—know they are likely to face retaliation, not reform.

And that makes even less sense when considering that mandatory civil rights reporting infrastructure already exists. Under Section 709(c) of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) already collects standardized, mandatory workforce demographic data through its EEO Data Collections:

EEO-1: Private employers with 100+ employees and federal contractors with 50+ must report data by job category, sex, and race/ethnicity.

EEO-3: Local referral unions submit member and applicant data by race and sex.

EEO-4: State and local government employers report by job classification, salary band, and demographic group.

EEO-5: Public K–12 school systems report by role, race, and sex.

These reports allow the federal government to detect workforce inequities, monitor compliance, and respond to systemic patterns of exclusion. But they are only half the picture. They tell us who is being hired—but not how employees are treated once inside or how often their rights are violated and then quietly settled.

It’s time to fix that. Congress should expand the EEO reporting system to include a new “Component 2: Civil Rights Liability Disclosure”—a mandatory biennial report, filed alongside EEO-4, requiring state and local public employers (including police departments) to report:

All settlements and judgments arising from claims under Title VII, Section 1983, the ADA, ADEA, or equivalent local laws;

The type of claim (e.g., sexual harassment, gender discrimination, retaliation), protected class categories involved, and amount paid;

A summary of the allegations, identifying the rank and role of the individuals involved (e.g., “female officer v. precinct commanding officer”), without compromising victim confidentiality;

Whether the alleged perpetrator was disciplined, retained, or promoted following the incident;

Aggregated, publicly accessible data, reviewed by the EEOC and the United States Department of Justice Civil Rights Division.

This expanded reporting would be a game-changer. It would allow the public, insurers, investors, federal oversight agencies, and municipal leaders to assess who is hired and how public institutions handle internal violations of civil rights law.

Its value would be far-reaching:

Investors could more accurately assess risk in municipal bonds and public contracts;

Insurers would have accurate data to underwrite municipal liability policies;

Workforce applicants—especially those from marginalized groups—could better evaluate where they can work safely;

Taxpayers would finally see how often their money is used to pay for misconduct rather than prevent it.

This is not about punishing institutions—it’s about incentivizing reform and protecting the public from repeat failures. Agencies with no history of discrimination payouts would benefit from proof of compliance. Agencies with chronic liabilities would be forced to confront the culture of impunity that perpetuates abuse. Either way, transparency is the first step.

If we can mandate EEO-1 reports from private companies and require public school districts to file EEO-5, we must also require law enforcement agencies to disclose when and why they use public funds to settle civil rights claims.

If we cannot see the problem, we cannot fix it. And right now, the problem is being paid to go away—again and again—with no accountability and no change.

Section 2: The Scale of the Problem – Billions in Payouts, Zero Accountability

One must look no further than the numbers to understand the full scope of institutional failure within law enforcement. From Fiscal Year 2016 through Fiscal Year 2023, the New York Police Department (NYPD) has cost taxpayers more than $1.3 billion in settlement payouts and judgments—often involving civil rights violations, excessive force, false arrests, and yes, sexual harassment, gender discrimination, and retaliation. Over this same period, the City of New York has paid well over $1.9 billion in total tort settlements. The NYPD consistently accounts for over one-third of that total, and in some years, significantly more.

In the Fiscal Year 2017, NYPD-related payouts spiked to $338.2 million, the highest in recent memory. By FY 2023, that number remained alarmingly high at $266.7 million, or 36.1% of all tort payouts citywide. These numbers do not include defense costs or internal disciplinary proceedings. They reflect direct financial liability—checks written, judgments paid—using public dollars.

And yet, for all this spending, we still cannot answer fundamental questions:

How many of these settlements involved sexual harassment or gender-based misconduct?

How many involved repeat offenders in supervisory or leadership roles?

How often were internal complaints filed before litigation, and how were they handled?

Were the officers or commanders responsible ever disciplined, transferred, or promoted?

How many non-disclosure agreements were included in these settlements, preventing survivors from speaking publicly?

These questions remain unanswered because no law requires law enforcement agencies to publicly track or report this data. While invaluable, the City Comptroller’s Annual Claims Report does not disaggregate the types of claims that fall under “NYPD tort payouts.” A $2 million settlement for wrongful death and a $500,000 settlement for sexual harassment are presented side by side without context or category. That lack of specificity is not an oversight; it is a design flaw in understanding and regulating institutional misconduct.

In the private sector, public companies must disclose material litigation and risks in their financial statements under SEC regulations. If a pattern of sexual harassment emerges, shareholders have a right to know because it implicates corporate governance, brand reputation, and financial exposure. When police departments pay millions to settle discrimination and harassment claims, no such transparency exists—even though the public is both shareholder and insurer.

The City’s litigation strategy also plays a significant role in concealing the true extent of sexual harassment and discrimination within public agencies. Many cases are settled quietly before discovery begins and typically without admitting wrongdoing. While this may serve the institution’s short-term interest in limiting reputational harm, it frequently undermines structural accountability. In New York, non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) in sexual harassment settlements are now restricted under Section 5-336 of the New York General Obligations Law, which prohibits confidentiality clauses unless the complainant specifically requests such terms. Even then, the law requires a 21-day review and 7-day revocation period, ensuring any NDA is truly voluntary. But in practice, institutional pressure, informal retaliation, and fears of professional blacklisting can lead survivors to accept confidentiality as a necessary trade-off for closure or safety.

These settlements are often treated internally as routine—the “cost of doing business”—written off in city budgets as litigation expenses, with no further review of the underlying conduct or the officials involved. However, what the public rarely sees is that some cases don’t settle at all. When survivors or their attorneys insist on exposure, accountability, or structural reform, the City often litigates aggressively. These cases drag on for years, consuming enormous public resources—only to result in more significant jury verdicts than the original settlement demand would have cost.

The final verdict often includes compensatory and punitive damages and statutory attorneys’ fees under federal and state civil rights laws. And beyond those hard costs, there’s a less visible but equally important budget line: billable hours spent defending the case. Outside counsel retained by the City—or in-house Law Department staff—spend hundreds of hours drafting motions, conducting depositions, and preparing for trial. These professional fees, whether billed externally or absorbed internally, represent taxpayer expenditures seldom publicly disclosed in annual claims reports.

If the public could see what a city paid to resolve a case and what it spent fighting it, we could have a far more honest conversation about litigation strategy, institutional values, and fiscal stewardship. Why spend five years defending an indefensible culture only to pay three times more than the original demand? Why fight transparency tooth and nail if the result is reputational damage, financial exposure, and retraumatization of survivors?

The answer lies in opacity—and that’s precisely what must change. A comprehensive civil rights liability disclosure framework must include settlement amounts, jury verdicts, defense costs, and legal hours expended. Only then can we understand the true financial burden of systemic discrimination and begin to demand better outcomes for both survivors and the public.

This lack of accountability is not just inefficient—it is dangerous. It fosters a culture of impunity, especially in environments like the NYPD, where rank, patronage, and silence can insulate powerful offenders. It undermines internal reporting mechanisms because potential whistleblowers know that internal investigations often lead to retaliation, not resolution. And it wastes taxpayer money—year after year—without structural change.

The bottom line: We are paying to protect the problem, not solve it. Until lawmakers require disaggregated reporting on settlements involving discrimination and harassment—especially in public safety institutions—these costs will continue to climb while trust in our institutions continues to fall.

Section 3: Case Studies – What the Public Wouldn’t Know Without Litigation or Leaks

Numbers alone don’t capture the human cost of institutional secrecy. Behind every settlement figure lies a person—often a woman, a person of color, or an LGBTQ+ employee—who stepped forward to report discrimination or harassment, only to be met with retaliation, silence, or both. The only reason the public has come to know about many of these cases is not because the City chose transparency but because litigation forced the truth into the open. Absent lawsuits or investigative journalism, these stories would remain hidden, their costs buried deep within city budgets.

Case Study 1: Captain Gabrielle Walls v. NYPD – A Culture of Protectionism at the Top

Captain Gabrielle Walls accused NYPD Chief of Department Jeffrey Maddrey—the highest-ranking uniformed officer in the department—of sexual harassment and retaliation dating back to 2015. According to court filings, Maddrey made repeated unwanted advances and retaliated against Walls after she rejected him. Despite the severity of the allegations, Maddrey ascended to the department’s top uniformed post. The City responded not with discipline or transparency but with litigation tactics designed to delay and deny. Walls’s federal lawsuit, filed in 2023 and amended in late 2024, is the only reason the public knows about these claims. Without her legal action, the entire matter—and the City’s exposure—would remain hidden.

Case Study 2: Police Officer Shemalisca Vasquez – Retaliated for Reporting Misconduct

Officer Shemalisca Vasquez alleged that she endured repeated sexual harassment, including unwanted explicit pictures, staged nudity, and lewd comments. When she filed internal complaints, she claimed she was targeted with retaliatory discipline, denied overtime, and marginalized professionally. Her lawsuit revealed a culture of denial and reprisal, particularly for women of color who step forward. While her case was eventually resolved, the settlement terms were not disclosed publicly, and no public discipline was issued to those responsible—once again, concealing institutional accountability from taxpayers.

Case Study 3: Lieutenant Angelique Olaechea – Retaliation for Testifying on Behalf of Another Officer

Lieutenant Angelique Olaechea was not the original complainant—she became a target because she supported another officer’s EEO complaint. After testifying in support of Officer Javier Velazquez, who had filed discrimination claims against supervisors in Manhattan’s 9th Precinct, Olaechea alleged she became the target of retaliatory conduct. NYPD leadership allegedly spread false rumors about a romantic relationship between the two officers and reassigned her to Brooklyn’s 79th Precinct under the pretext of a “pattern of unacceptable behavior.” She was issued five retroactive disciplinary charges, and although four were upheld, the timing and context pointed to retaliation. A departmental judge eventually recommended her termination, prompting her resignation.

Olaechea sued under federal civil rights law. In August 2021, a Manhattan jury awarded her $872,892.60 in damages for unlawful retaliation. The City attempted to challenge the verdict, and while the court later dismissed individual claims against Captain Vincent Greany, the jury’s finding of institutional retaliation stood. Had she not pursued litigation—and had a jury not intervened—her case would have been yet another unrecorded casualty of the NYPD’s internal politics.

Case Study 4: Captain Sharon Balli – Career Retaliation for Challenging Gender Discrimination

Captain Sharon Balli’s case is emblematic of how retaliation in the NYPD doesn’t spare even the most senior-ranking women. A highly decorated officer with a distinguished record, Balli alleged that after she raised concerns about discriminatory practices within the department, she was subjected to retaliatory reassignment, professional marginalization, and eventual removal from command. Her complaints were not isolated grievances—they were grounded in broader concerns about gender-based bias in promotional opportunities and command assignments.

Despite her tenure, leadership experience, and exemplary service record, Balli became expendable once she challenged the internal power structure. Like other high-ranking women in the department who have voiced concerns, Balli was met not with internal reform but with silent retaliation—an institutional pattern designed to send a message to others: speak out, and you will be sidelined.

Her case reinforces a troubling reality: that the NYPD’s leadership culture still treats dissent, especially from women in power, as a threat to be neutralized rather than an opportunity for reform. As with other cases, her allegations would likely have remained hidden if not for litigation and persistent advocacy.

Case Study 5: Officer Ann Cardenas – A Precinct Culture Described as a “Sordid Frat House”

Officer Ann Cardenas brought a sexual harassment lawsuit against the City of New York, her former supervisor Sergeant David John, and fellow officer Angel Colon, exposing pervasive and explicit misconduct at the 83rd Precinct in Bushwick, Brooklyn. According to her federal complaint, Sgt. John routinely referred to Cardenas as his “work p—y,” made repeated sexually explicit remarks, kissed her without consent, and physically harassed her on multiple occasions. In one particularly egregious incident, he allegedly admitted to masturbating to a photo of her on Facebook.

After Sgt. John retired in 2014, but the harassment continued. Officer Colon allegedly escalated the abuse by making violent sexual threats and initiating unwanted physical contact, including saying he would “rape her in a good way.” Despite internal complaints, the workplace culture enabled, not restrained, such conduct.

In a damning opinion, U.S. District Judge Ann Donnelly described the precinct as a “sordid frat house” and ruled that both officers could be held personally liable, rejecting arguments that their behavior fell outside the scope of employment. In April 2018, the case was settled for $535,000—with the City paying $500,000 and John and Colon paying $20,000 and $15,000, respectively, out of pocket. Notably, the City declined to defend the individual officers, an unusual but telling break from standard practice.

This case illustrates that the public can see institutional failures vividly when lawsuits proceed far enough and survivors withstand the pressure to settle early. But that level of transparency is the exception, not the norm. Absent federal court litigation, the facts of Cardenas’s experience would likely have remained buried, and her harassers might never have faced personal consequences.

Patterns Across Cases: The Blueprint of Institutional Betrayal

What these cases reveal is not isolated misconduct but a systemic strategy:

Allegations of harassment or discrimination are minimized internally or ignored;

Those who speak out—whether victims or allies—are often transferred, disciplined, or discredited;

The City’s legal strategy prioritizes reputation over reform;

Some cases are quietly settled with NDAs or sealed stipulations, while others are litigated at significant cost, only to result in even more substantial jury awards;

The public is unaware of the circumstances, personnel, and departments involved—even as it funds the payouts.

Even when verdicts like Olaechea’s occur, they are treated as anomalies, not indicators of broader cultural dysfunction. There is no central repository tracking how many NYPD employees have prevailed in retaliation lawsuits, how many millions in public funds have been spent defending or settling these cases, or whether any individuals involved were disciplined.

Until we change the law and require comprehensive, disaggregated reporting of civil rights liability—including settlements, verdicts, legal costs, and internal disciplinary outcomes—we will continue to rely on lawsuits and whistleblowers to reveal the truth. And by then, it’s almost always too late—for careers, justice, and public trust.

Section 4: Legal Infrastructure Failure – Why Misconduct Data Stays Hidden

The public pays for civil rights violations, but the law doesn’t guarantee that the public gets to see them.

No federal or New York State law requires police departments—or any public agency—to publicly report how often they settle discrimination, harassment, or retaliation claims, how much they pay, or whether the same individuals or units are involved in repeated offenses. The Comptroller’s Annual Claims Report aggregates payout data by agency but not by claim type, protected class, or repeat offender. It’s possible to know the NYPD paid $266.7 million in settlements last year—but impossible to know how much of that involved sexual harassment, racial discrimination, or retaliation.

Attempts to uncover that information through FOIL (Freedom of Information Law) are often delayed or denied. Agencies cite exemptions for litigation, internal disciplinary processes, or personnel privacy to withhold basic accountability data. Even when lawsuits are filed, most settle without admitting wrongdoing and with confidentiality provisions that keep misconduct hidden from the press, policymakers, and the public.

The EEOC’s current reporting system also falls short. While EEO-1 and EEO-4 reports track workforce demographics, there is no corresponding system for reporting when those rights are violated and settlements are paid. This is a structural failure—not just of policy but of oversight.

Until Congress or the states require public employers to disclose this data—just as we need public companies to report litigation risk—civil rights liability will remain the most expensive secret in government.

Nowhere is this more financially consequential than in law enforcement.

Section 5: Why Transparency Is Not Just Ethical—It’s Financially Essential

Transparency in civil rights settlements is not just a moral imperative—it’s a financial necessity. When cities like New York spend hundreds of millions of dollars settling sexual harassment, retaliation, and discrimination lawsuits without disclosing the specifics, they are failing not just survivors but also taxpayers, bondholders, insurers, and future employees. Every secret payout hides the true cost of institutional misconduct, distorts risk, and undermines long-term fiscal accountability.

Consider this: a city that quietly settles dozens of sexual harassment claims against the same department or leadership team year after year creates reputational, legal, and financial risk—but none of that is captured in public-facing audits or budget documents. There is no mechanism for insurers to adjust liability premiums based on settlement history. There is no pathway for investors in municipal bonds to understand how systemic misconduct may affect long-term operational risk. There is no way for legislators or the public to evaluate which agencies are most exposed—or why.

This lack of visibility also distorts litigation strategy. As discussed earlier, the City often defends indefensible cases at great expense. When litigation drags on, legal costs skyrocket—whether paid to outside counsel or borne by salaried City Law Department staff. In cases like Lieutenant Angelique Olaechea’s, where a jury ultimately awarded nearly $900,000 for retaliation, the City likely spent hundreds of additional hours on internal defense efforts before paying the judgment. These hours—along with outside expert fees, deposition costs, and court expenses—are rarely tracked publicly as part of the total cost of misconduct.

Worse still, settlement costs are often siloed—treated as separate from agency operating budgets. When the NYPD racks up $250 million in annual settlements, that figure isn’t counted against its command structure or leadership performance. There is no accountability loop between financial loss and operational reform. Settlements are absorbed by the City as general litigation costs, disconnected from the command decisions that led to them.

A comprehensive, mandatory reporting system would change that. It would align financial exposure with internal management and risk controls. Just as public companies must disclose “material litigation” to shareholders, public agencies should be required to report settlements and verdicts involving civil rights violations—especially when taxpayer funds are used to resolve them.

Transparency is prevention. It allows insurers to price risk accurately. It empowers legislators to target reform efforts. It warns job applicants about unsafe workplace cultures. It also gives the public an accurate accounting of how much they spend—not just on police but also on protecting the institution from accountability.

Without mandatory disclosure, cities can continue to treat civil rights violations as a cost of doing business. With it, they must treat them as what they are: evidence of more resounding institutional failure, demanding systemic correction.

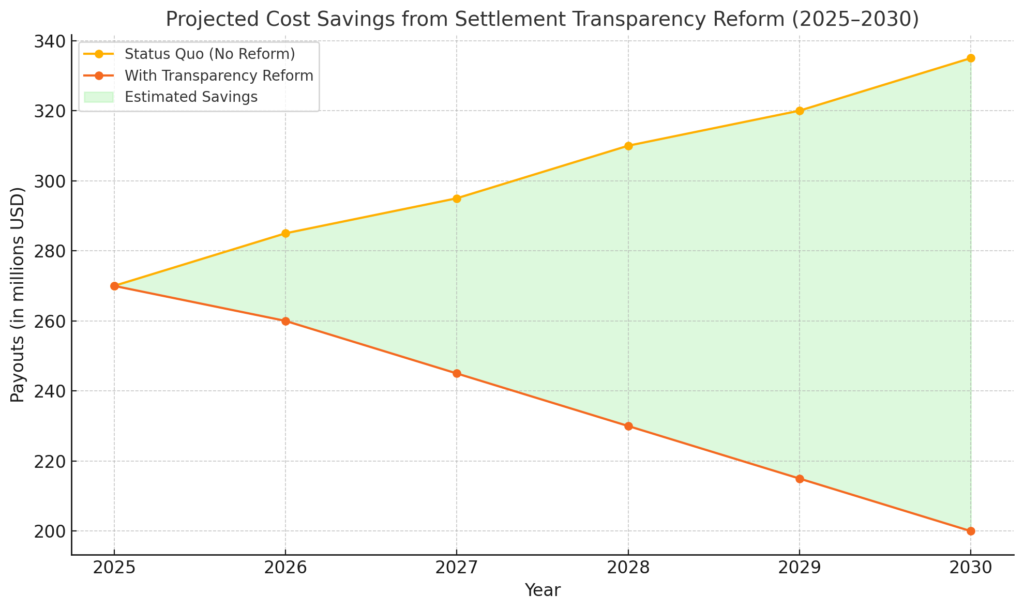

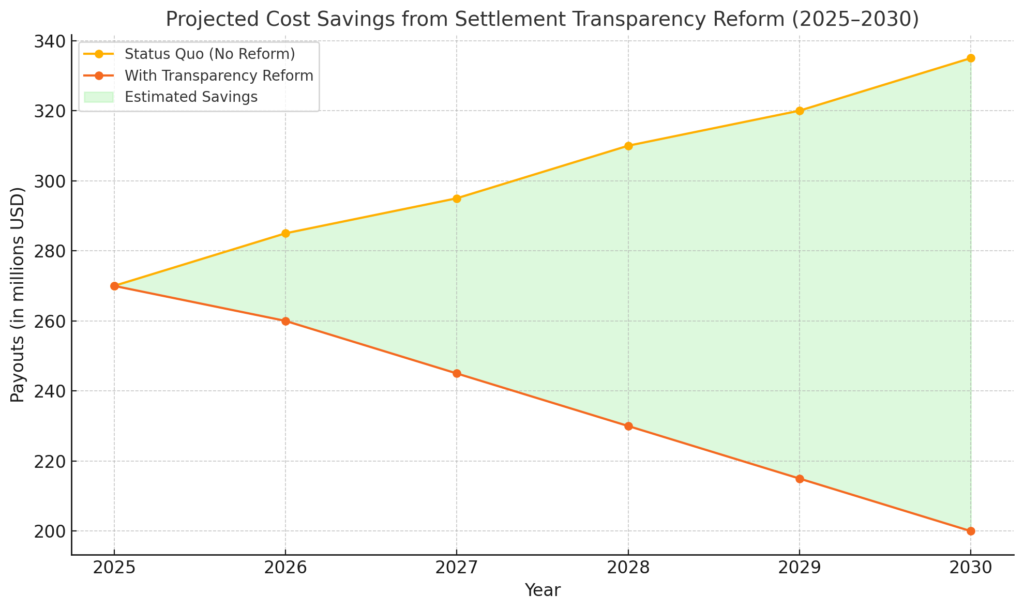

Projected Savings from Transparency Reform

A financial model comparing the City’s current litigation trajectory with a transparency-based reform scenario shows concrete fiscal benefits. Under the status quo, settlement payouts related to civil rights violations are projected to rise from $270 million in 2025 to $335 million by 2030, totaling $1.815 billion over six years.

By contrast, a transparency reform model—with mandated public reporting of claim type, protected class, and agency response—could significantly reduce these costs through earlier intervention, deterrence of repeat offenses, and informed oversight. In that model, projected payouts decline steadily, from $270 million in 2025 to $200 million by 2030, for a six-year total of $1.42 billion.

Estimated six-year savings: $395 million.

These savings don’t even account for:

Legal defense and administrative costs saved through earlier resolution;

Lower insurance exposure for self-insured municipalities;

Productivity gains from avoiding years-long litigation;

Risk-adjusted municipal bond pricing improvements.

This isn’t speculation—it’s innovative governance. When agencies must account for the full cost of civil rights violations, they are incentivized to prevent them. Transparency is prevention, and prevention is savings.

Section 6: A Path Forward – What New Legislation Should Require

If we are serious about addressing systemic discrimination, sexual harassment, and retaliation within public institutions—particularly law enforcement—we must move beyond isolated lawsuits and toward structural accountability. That begins with legislation.

Federal and state lawmakers should mandate annual disclosure of civil rights settlements and judgments involving public employers, including but not limited to police departments, school districts, transit authorities, and state agencies. This disclosure must go beyond aggregate numbers to provide the specificity for prevention, oversight, and reform.

The following is a legislative framework to achieve those goals.

1. Federal Legislation: A New EEO Component 2

Congress should direct the EEOC and DOJ Civil Rights Division to create a new mandatory reporting requirement—Component 2: Civil Rights Liability Disclosure—to be filed biennially alongside existing EEO-4 reports. This report would apply to all public employers with 100 or more employees, including state and local governments, law enforcement agencies, school districts, and public universities.

The Component 2 report should include:

All settlements and judgments related to:

Title VII (discrimination, harassment, retaliation);

Section 1983 (constitutional violations under color of law);

ADA, ADEA, Equal Pay Act, and equivalent state/local laws.

Disaggregated data, including:

Nature of the claim (e.g., gender-based harassment, race discrimination, retaliation);

Protected class category (e.g., sex, race, disability);

Dollar amount paid;

Role and rank of alleged offender (e.g., “sergeant,” “civilian supervisor”);

Whether the alleged offender was subject to discipline, transfer, promotion, or resignation.

Legal defense costs, including estimated billable hours or outside counsel fees where available.

Redacted narrative summaries of each case, with survivor anonymity preserved but essential facts disclosed.

Data submission to a federal portal, to be maintained by the EEOC or DOJ and made accessible in aggregated format to Congress, state attorneys general, auditors, and the public.

2. State-Level Legislation: Public Integrity Through Transparency

States like New York can—and should—act now, independent of federal action. A statewide Public Civil Rights Settlement Disclosure Act should:

Require all municipalities, counties, and public agencies to report annually:

Every settlement or judgment involving discrimination, harassment, or retaliation;

Name of the agency and department involved;

Type of claim and protected class;

Amount paid and source of funds;

Whether any post-claim personnel action occurred (discipline, resignation, promotion).

Direct state comptrollers or attorneys general to maintain a public database, updated annually, and cross-referenced with:

Budget allocations for legal defense;

Insurance policy premium changes;

Repeat offenders or units.

Require the publication of a statewide annual report, identifying high-risk agencies, trends by category, and policy recommendations for intervention.

Include whistleblower protections and anti-retaliation provisions for public employees who report misconduct or disclose concealed settlements.

3. Tie Disclosure to Public Funding and Insurance

Make disclosure a condition of eligibility for:

Federal or state grants (e.g., DOJ COPS grants, state infrastructure aid);

Law enforcement accreditation programs;

Municipal bond credit enhancements.

Encourage private insurers and municipal reinsurance pools to incentivize disclosure with premium reductions or risk-rating adjustments based on:

Transparency practices;

Frequency and severity of claims;

Demonstrated commitment to corrective action.

No More Business As Usual

For too long, public agencies—especially police departments—have been allowed to treat civil rights settlements as confidential transactions, shielded from oversight and unaccounted for in agency performance reviews. That must end. Transparency is not punishment. It is a policy tool that aligns fiscal responsibility with public integrity.

Cities, states, and Congress must act to pull these patterns into the light. As this blog has shown, the legal frameworks exist. The data already exists. What’s missing is the mandate to disclose it.

Let the law require what ethics and evidence demand: a public record of public wrongdoing—and a system that learns from its failures.

Section 7: Conclusion – You Can’t Fix What You Don’t Track

Every year, public agencies settle discrimination, harassment, and retaliation claims behind closed doors. Victims are silenced. Offenders remain employed. The public foots the bill. The institutions responsible face no meaningful consequences because no law requires them to disclose what happened, why, or what they did in response.

This is not just a crisis of misconduct—it is a crisis of accountability. We have allowed law enforcement and other public employers to operate in a legal blind spot, where systemic civil rights violations are addressed in courtrooms, not legislatures, in settlements, not reforms.

We know better now. The data exists. The financial toll is precise. The damage to careers, credibility, and public trust is ongoing. And yet, the most dangerous aspect of this problem is its invisibility. As long as civil rights liability remains untracked and unreported, institutional betrayal will continue to be funded, normalized, and repeated.

We don’t allow private corporations to hide material litigation risks from their shareholders. We don’t allow federal contractors to conceal their workforce demographics from compliance agencies. Why, then, do we allow law enforcement agencies to hide repeated civil rights violations from the people they are sworn to serve?

We cannot continue relying on lawsuits, whistleblowers, and journalists to do the work our laws should mandate. It is time to legislate transparency. It is time to require public agencies to disclose their civil rights exposure just as they disclose their budgets, audits, and public contracts.

Because the truth is simple: You can’t fix what you don’t track.

If you’re a legislator, advocate, journalist, or concerned citizen, this is the moment to demand transparency. Public money should not be used to fund silence.

About the Author

Eric Sanders, Esq. is a New York-based civil rights attorney and president of The Sanders Firm, P.C. With over two decades of experience litigating cases involving sexual harassment, discrimination, police misconduct, and retaliation, Mr. Sanders has represented hundreds of clients against some of the most powerful institutions in New York City. His work has exposed systemic failures within the NYPD and other public agencies, and he continues to advocate for transparency, accountability, and institutional reform at every level of government.