I. Introduction

In the New York City Police Department, retaliation isn’t a deviation from the rules—it’s embedded in them. Codified under New York City Administrative Code § 14-115, the Police Commissioner possesses sweeping authority to initiate disciplinary action against any member of the force for “conduct prejudicial to the good order, efficiency or discipline of the department.” On its face, the statute purports to promote integrity and accountability. In practice, it serves as a legal cudgel, wielded not to punish misconduct but to silence dissent.

For over 175 years—since its founding in 1845—the NYPD has maintained a culture that rewards silence and punishes resistance. From labor organizers in the early 20th century to modern-day whistleblowers who expose racism, corruption, or sexual abuse, the department has consistently responded to internal critique with discipline, demotion, or dismissal. What has changed is not the instinct to retaliate, but the legal mechanisms used to accomplish it.

Today, § 14-115 functions as a structural weapon—a catch-all disciplinary provision invoked when the department wants to remove someone without explaining why. No external review is required, no judicial finding is necessary, and no independent oversight body is consulted before a referral is made. This law turns the NYPD’s disciplinary system into an inescapable trap for officers who speak out: speak and be punished, or stay silent and survive.

This article will expose the proper function of § 14-115 by situating it within the NYPD’s long-standing pattern of internal retaliation. It will unpack the statute’s language and legislative history, dissect the structural imbalance it creates, and illustrate its modern misuse through real case examples. It will argue that § 14-115 is not just a disciplinary statute but an institutional suppression tool, immune from oversight and cloaked in legitimacy. It will also call on lawmakers, judges, and civil rights advocates to confront this abuse of legal authority before it silences another voice.

II. Statutory Overview

At the heart of the NYPD’s disciplinary regime lies New York City Administrative Code § 14-115, a provision deceptively brief in language but vast in reach. The full operative text reads:

“The commissioner shall have power, in his or her discretion, on conviction by the commissioner, of a member of the force of any criminal offense or neglect of duty, violation of rules, or neglect or disobedience of orders, or conduct injurious to the public peace or welfare, or immoral conduct or conduct unbecoming an officer, or any breach of discipline, or the rules and regulations of the department, to punish the offending party by reprimand, forfeiting and withholding pay for a specified time, suspension, or dismissal from the force.”

A. Legislative Intent: Broad Disciplinary Discretion

The legislative purpose of § 14-115 was to centralize control in the hands of the Police Commissioner, enabling swift internal discipline to maintain order and efficiency. The statute grants the Commissioner authority akin to a judge, jury, and executioner. It envisions a paramilitary hierarchy where discipline is absolute, and internal correction can occur without external interference.

But the law is silent on procedural safeguards. There is no requirement that an independent investigation precede discipline, no mandate that evidence meet judicial standards of admissibility, and no guarantee that protected conduct, such as whistleblowing or filing a United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) charge, will be insulated from retaliatory interpretation as “conduct unbecoming.”

Notably, § 14-115 traces its origins back to the early 20th century, with its current form dating to a 1977 recodification under the New York City Administrative Code. The statutory language has changed little since, despite the passage of significant state and federal whistleblower protections such as the Civil Service Law § 75-b, Title VII amendments, and the New York Labor Law §740. This timeline reveals a deeper problem: § 14-115 is a pre-modern disciplinary statute governing a post–civil rights era workplace. Its structural design predates contemporary notions of due process, workplace rights, and constitutional protections for dissent.

B. The Elasticity of “Conduct Unbecoming”

The statute’s vague phrasing—terms like “neglect of duty,” “immoral conduct,” and “conduct unbecoming of an officer”—creates a blank check for disciplinary retaliation. These are not defined terms. They are open-ended character judgments subject to departmental whim and political expediency. The NYPD has used these categories to discipline whistleblowers, union activists, and officers who challenge internal corruption or discriminatory practices.

For example, officers who report wrongdoing may suddenly be accused of insubordination, inefficiency, or disloyalty—charges that neatly fit the “conduct prejudicial” clause without requiring a clear factual predicate. And because § 14-115 does not distinguish between actual misconduct and protected speech, it becomes the perfect tool to recast protected activity as a punishable offense.

C. Judicial Deference and the Absence of Oversight

Compounding the problem is the extreme judicial deference courts have shown to § 14-115 disciplinary decisions. Under New York administrative law, courts rarely disturb the Commissioner’s findings unless they are “arbitrary and capricious” or lack any rational basis. This deferential standard, rooted in Matter of Pell v. Board of Education, 34 N.Y.2d 222 (1974), creates a near-insurmountable barrier to challenging internal NYPD discipline, even when retaliatory. So long as the department can articulate a minimally plausible justification, courts will typically uphold the action, no matter how pretextual or selective the enforcement may be.

Moreover, the Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB) and the Department of Investigation (DOI)—theoretically empowered to provide independent oversight—have no formal role in reviewing or approving § 14-115 referrals. The decision to discipline remains almost entirely internal, shielded by legal presumptions of good faith and reinforced by administrative silence. The result is a system where retaliation can be easily disguised as legitimate discipline, with no meaningful check from the outside.

III. Structural Power: Why § 14-115 Is Ripe for Abuse

The danger of § 14-115 is not simply in its language but in the power structure it authorizes. It grants the Police Commissioner unilateral authority to initiate, adjudicate, and impose discipline within a closed, unreviewable system. There is no independent gatekeeper, no meaningful evidentiary threshold, and no requirement that the accused officer be afforded constitutional due process beyond what the department itself decides is sufficient. In this vacuum, retaliation masquerades as regulation.

A. One-Way Power: The Commissioner as Prosecutor and Judge

Unlike other employment contexts where discipline is subject to independent arbitration or neutral oversight, the NYPD’s internal disciplinary process under § 14-115 concentrates nearly all authority within the department’s command hierarchy. The Police Commissioner possesses unilateral power to initiate charges, convene internal trials, and impose or modify discipline—all without external review.

Departmental trials are generally conducted before the Deputy Commissioner of Trials, with cases typically heard by Assistant Trial Commissioners—all of whom are appointed by, and ultimately answerable to, the Police Commissioner. These officials issue recommended findings and penalties, but the Commissioner retains absolute discretion to adopt, modify, or outright reject those recommendations, regardless of the trial’s evidentiary record. The result is a closed disciplinary loop where those adjudicating the matter operate within the same institutional chain of command as those prosecuting it.

This structural design compromises the neutrality of the process. When the same authority controls the initiation of charges, the oversight of the trial mechanism, and the final disciplinary decision, there is no meaningful separation of powers. The process is not designed to ensure fairness but to enforce obedience. If the Commissioner or senior leadership seeks to punish a whistleblower, they need not prove actual misconduct; they need only frame the officer’s protected conduct as “prejudicial to good order” or “conduct unbecoming,” and the internal system will do the rest.

B. No External Review Required

Section 14-115 does not require review by any external body before disciplinary action. There is no obligation to consult the CCRB, the DOI, or any labor tribunal before imposing penalties. This lack of procedural checkpoints means that disciplinary referrals can be made pretextually—in retaliation for protected activity like filing a complaint, reporting misconduct, or testifying in a legal proceeding.

Even the New York City Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings (OATH) plays no role unless explicitly delegated, which is rarely true in internal police discipline. This makes § 14-115 functionally autonomous from the rest of the city’s civil service oversight apparatus.

C. The “Closed Loop” of Institutional Retaliation

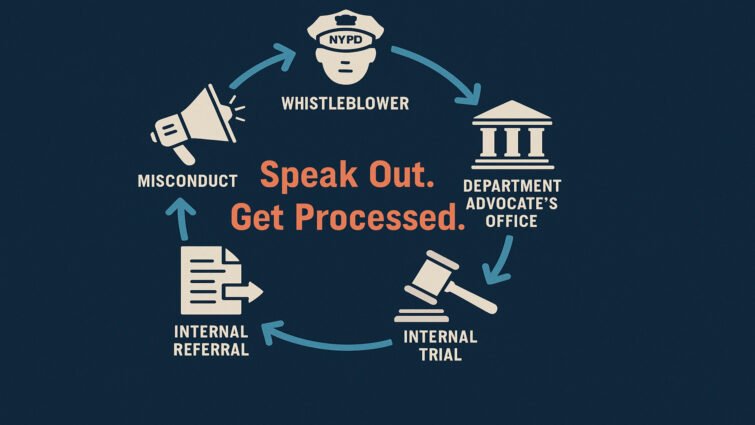

What emerges is a closed loop:

An officer reports misconduct or exercises a protected right.

That officer is then targeted with a § 14-115 referral for allegedly “disruptive” or “insubordinate” behavior.

The NYPD’s internal legal apparatus frames the conduct as a threat to discipline.

Departmental trials or psychological evaluations are initiated, not to discover the truth, but to validate a predetermined outcome.

The officer is disciplined, transferred, suspended, or pressured into resignation, with no outside review.

This loop does not just punish dissent—it deters it. Officers learn quickly that challenging corruption, racism, or abuse will not be met with support or investigation, but with retaliation rebranded as “discipline.” In this way, § 14-115 operates as both sword and shield: enabling retaliation while cloaking it in institutional legitimacy.

IV. Historical Context: Retaliation Is Not a Bug—It’s a Feature

To understand how § 14-115 became a suppression tool, one must examine the NYPD’s institutional DNA. Retaliation against internal dissenters is not an aberration but a defining feature of the department’s history. Since its founding in 1845, the NYPD has operated less as a public accountability institution and more as a vertically controlled paramilitary agency where loyalty to the chain of command supersedes legal or ethical obligations to the public.

The disciplinary mechanisms that would later be codified in § 14-115 were born in an era that predated modern concepts of workplace rights, due process, and statutory whistleblower protections. The statute in its present form was recodified in 1977, before the Supreme Court expanded public employee First Amendment rights and long before the rise of state and federal whistleblower laws. As a result, the system reflects the values of a bygone era: obedience over oversight, control over accountability.

A. From the Rattle Watch to the Rubber Stamp

The NYPD’s roots trace back to the “rattle watch” constables of Dutch New Amsterdam. However, when the modern force was formalized in 1845, it was modeled after the hierarchical and often brutal London Metropolitan Police. Almost immediately, rank-and-file officers who challenged misconduct, political interference, or discriminatory practices were disciplined, demoted, or dismissed.

The department’s earliest disciplinary systems were rudimentary and opaque—commanders had unchecked authority to suspend officers for anything deemed disloyal. This legacy hardened into formal policy as administrative codes like § 14-115 were codified, not to protect public integrity, but to consolidate internal obedience.

B. Suppressing Dissent Across Eras

The NYPD’s history of silencing whistleblowers is well-documented. During the Progressive Era, officers who exposed political patronage or racketeering within the force were punished as “disruptors.” In the 1960s and 1970s, whistleblowers like Frank Serpico and David Durk faced life-threatening retaliation for exposing systemic corruption—a retaliation culture publicly condemned by the Knapp Commission, yet never structurally resolved.

In the post-9/11 era, dissent took new forms: officers criticizing racial profiling, mass surveillance, or the abuse of stop-and-frisk found themselves targeted. Rather than address the claims, the department responded with psychological referrals, negative evaluations, or § 14-115 charges and specifications designed to paint the whistleblower as unstable, disloyal, or insubordinate.

C. DOJ Findings: A Persistent Pattern of Retaliation

The U.S. Department of Justice, in its various investigations of municipal police departments across the country, has identified a common thread: retaliation against whistleblowers and internal critics is deeply embedded in police culture. Though the NYPD has largely avoided formal DOJ consent decrees, internal documents and historical inquiries reveal the same pattern, particularly when complaints involve racism, sexism, or abuse by senior command.

A 2020 review by the New York City Equal Employment Practices Commission of the NYPD’s Sexual Harassment Prevention and Response practices for the Audit Period January 1, 2019, through December 31, 2020, revealed that officers who reported discrimination were more likely to face adverse employment action than those accused of perpetrating it. Yet this damning fact was buried in procedural reform language and never acted upon. § 14-115 remains fully intact.

D. Retaliation Is Institutional, Not Incidental

The through-line across decades is clear: the NYPD does not tolerate internal dissent—it punishes it, often through internal policies that predate modern civil rights protections. It is not an isolated misuse when § 14-115 is invoked against a whistleblower. It is the latest chapter in a department-wide practice of using structurally outdated legal tools to suppress lawful speech and punish moral courage.

V. Case Studies: When Whistleblowing Becomes a Crime

In a healthy law enforcement agency, whistleblowers are protected, not punished. But under the NYPD’s disciplinary regime, particularly through Administrative Code § 14-115, internal dissent is often treated as a betrayal that must be neutralized. Officers who speak out against corruption, discrimination, or abuse are rarely met with fair hearings or good-faith dialogue. Instead, they face retaliation disguised as discipline: internal charges, mental health referrals, drug tests, integrity stings, and performance sabotage.

These aren’t theoretical risks. They are recurring patterns that are well-documented in litigation and internal records. Below are four illustrative categories—each connected to § 14-115 and routinely weaponized to punish officers who dare to break ranks.

A. Psychological Referrals as Career Sabotage

One of the most chilling tools of retaliation is the psychological referral, framed as a concern for officer wellness, but often deployed as a credibility strike. Officers who report sexual harassment, racial discrimination, or command corruption are frequently sent for psychological evaluation within weeks of speaking out.

In one case, an officer with over a decade of decorated service filed an internal report regarding sexual favoritism in overtime assignments. Two weeks later, her precinct commander claimed she appeared “agitated” during a meeting and referred her to Psychological Services for “fitness for duty” testing. No incident report was filed. No colleagues corroborated the claim. Still, she was stripped of her firearm, reassigned to desk duty, and flagged as “potentially unstable.” The NYPD initiated § 14-115 charges for “conduct unbecoming,” citing her “hostile tone” and “failure to accept supervisory feedback.”

In practice, these referrals function as administrative exiles. They damage promotional prospects, justify suspension or modified duty, and shift the narrative from whistleblower to unstable employee without a single evidentiary hearing.

B. Drug Testing as a Pretext for Termination

Random drug testing is a legitimate safety tool—until it’s selectively used against internal critics. Officers who challenge department misconduct are increasingly subject to sudden, “random” hair drug tests. The results, particularly when processed by third-party contractors like Psychemedics, have led to disciplinary charges under § 14-115, even without corroborating evidence.

In one case, a Black officer who filed a formal complaint about discriminatory shift assignments was called in for drug testing the day after refusing to falsify an arrest report. Though he tested negative on multiple independent screenings, the NYPD proceeded with § 14-115 charges based solely on the original test, allegedly positive for marijuana. He was suspended without pay, accused of “immoral conduct,” and placed in a prolonged disciplinary process. Despite the lack of criminal charges, the department moved to terminate.

Hair drug testing, particularly in departments with opaque selection algorithms and limited appeal rights, has become an expedient tool to force out inconvenient employees under the pretense of neutral enforcement.

C. Integrity Tests as Entrapment for Dissenters

Another covert tactic increasingly used to punish whistleblowers is the so-called “integrity test.” These staged operations—where Internal Affairs plants bait such as money, contraband, or conduct triggers—are ostensibly used to weed out corruption. But in reality, they are often deployed against officers who have filed complaints, testified against superiors, or refused to participate in unlawful acts.

In one incident, a Latino officer who raised concerns about falsified overtime slips and ghost tours in his command was the subject of an integrity test involving a planted wallet with marked bills during a civilian encounter. Despite immediately turning the item in, he was subjected to a full misconduct investigation, with Internal Affairs claiming he failed to notify a supervisor “in a timely manner.” § 14-115 charges were initiated for “neglect of duty” and “conduct prejudicial to good order.”

These tests are not random. They are calculated traps—targeted at internal critics, designed to manufacture infractions that justify termination without exposing the real reason: protected activity.

D. Weaponizing Performance Metrics and CRAFT

The NYPD’s internal performance system, including the Cop Rapid Assessment Feedback Tool (CRAFT), has long been criticized for incentivizing arrests and penalizing discretion. But it also serves another purpose: retaliation. When an officer files a complaint or cooperates with an investigation into departmental misconduct, their performance metrics often mysteriously decline.

In one case, a female sergeant who testified in support of a colleague’s racial discrimination complaint saw her CRAFT scores plummet. She was accused of lacking “command presence” and failing to “motivate subordinates,” despite a track record of above-average evaluations. Months later, she was brought up on § 14-115 charges for “failure to meet performance expectations.” She was denied promotion, reassigned to a less desirable shift, and her professional record was permanently tainted—all for engaging in conduct protected under law.

Because performance metrics are internally controlled and often subjective, they provide ideal retaliation coverage, allowing leadership to penalize whistleblowers without admitting the real motive.

E. The § 14-115 Playbook: Legitimizing Retaliation

In all of these examples, a clear pattern emerges:

Protected activity triggers retaliation.

Neutral-sounding enforcement tools are deployed selectively.

§ 14-115 is invoked to create a legal basis for discipline.

Internal actors frame the retaliation as “maintenance of order.”

There is rarely documentation tying the retaliation directly to the protected activity—that’s the point. § 14-115’s broad language enables the NYPD to build a parallel justification that courts and oversight bodies often accept at face value.

This is not accountability. This is institutional self-preservation, executed through bureaucratic sabotage and codified in law.

VI. Legal Analysis: Misuse of Authority vs. Due Process

The invocation of Administrative Code § 14-115 to punish whistleblowers implicates core constitutional protections. Though framed as internal discipline, the NYPD’s misuse of this statute often masks retaliatory state action. When § 14-115 is weaponized against officers who speak out on matters of public concern, such as unlawful quotas, discrimination, or abuse of power, it raises serious questions under the First and Fourteenth Amendments.

A. First Amendment Retaliation: When Internal Speech Is Protected Citizen Speech

The First Amendment protects public employees from retaliation when they speak as citizens on matters of public concern, even if the speech occurs inside the workplace. The legal test, as refined by Garcetti v. Ceballos, 547 U.S. 410 (2006), and applied by the Second Circuit in Matthews v. City of New York, 779 F.3d 167 (2d Cir. 2015), turns on two factors:

Whether the speech was made consistent with the employee’s official duties, and

Whether the speech had a civilian analogue—whether a private citizen could have raised the concern through the same channel.

In Matthews, an NYPD officer internally reported an unlawful arrest quota system, arguing that it distorted officer discretion and damaged community trust. The department retaliated with punitive assignments, denial of overtime, and adverse performance evaluations. The district court dismissed his First Amendment claim, holding he spoke as an employee. But the Second Circuit reversed, holding that Matthews spoke as a citizen because his complaints fell outside his formal duties and were made through a channel also available to civilians—his commanding officers, who routinely engaged with the public through Community Council meetings and civic outreach.

This decision matters profoundly in the § 14-115 context. It establishes that internal NYPD speech can be constitutionally protected, especially when it critiques department-wide policies like quotas, racial profiling, or abuse of force protocols. Notably, the court rejected the notion that general NYPD rules requiring members to report misconduct could convert all such speech into “employee speech” and thereby strip it of First Amendment protection. If that logic were accepted, the court warned that agencies could immunize all retaliatory discipline simply by expanding job descriptions to cover every potential disclosure.

In practice, officers who blow the whistle on systemic misconduct—and are later charged under § 14-115 for “conduct unbecoming” or “disruptive behavior”—may have a viable constitutional retaliation claim, even if the speech occurred internally. Matthews confirms that what matters is not proximity to command but whether the speech involved policy critique, not task performance.

B. Fourteenth Amendment: Due Process and Arbitrary Power

Beyond speech rights, § 14-115’s design and use raise procedural due process concerns under the Fourteenth Amendment. Public employees with civil service protections are entitled to notice, a meaningful response opportunity, and a fair adjudicatory process. But these rights are often illusory under the NYPD’s application of § 14-115.

Charges are initiated unilaterally, often based on vague allegations like “neglect of duty” or “disrespectful conduct.”

Trials are conducted by subordinate officers beholden to the same leadership that initiated the charges.

Final authority lies with the Police Commissioner, who can adopt, modify, or reject trial recommendations without external oversight.

When § 14-115 punishes whistleblowers, this internal structure ensures that retaliation is procedurally authorized and insulated from review. There is no meaningful distinction between accuser, adjudicator, and executioner. This violates the letter and spirit of due process, which requires adjudication by a neutral arbiter and decisions based on facts, not internal politics or reprisal.

Moreover, vague statutory standards—like “conduct prejudicial to the good order of the department”—invite arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement, which courts have long viewed with suspicion in the constitutional context. See Grayned v. City of Rockford, 408 U.S. 104, 108–09 (1972) (due process violated by vague standards that encourage discriminatory application).

C. The Pretext Barrier: How Legal Doctrine Shields Retaliation

Despite these constitutional protections, officers disciplined under § 14-115 face a high hurdle: judicial deference to internal discipline. Courts routinely uphold adverse actions if the department offers a rational justification, even if the officer alleges retaliation for protected conduct.

This Pell legacy allows disciplinary findings to stand unless they are “shocking to one’s sense of fairness.” In the federal context, this deference often intersects with the Pickering balancing test, which weighs the government’s interest in efficiency against the employee’s right to speak.

In practice, this means departments like the NYPD can offer a superficial performance rationale—e.g., “conduct unbecoming” or “insubordination”—to mask the real motive: retaliation for protected speech. Without documentary smoking guns or witness corroboration, plaintiffs are often left fighting pretext with little more than temporal proximity and patterns of disparate treatment.

This is why Matthews is so important: it clarifies that speech addressing systemic misconduct, even when made internally, can trigger constitutional protection. Courts must not allow § 14-115’s procedural veneer to obscure its substantive misuse.

D. Structural Retaliation Is a Constitutional Harm

When a statute like § 14-115 is used not to uphold discipline, but to eliminate dissent, the harm is not just individual—it is institutional. It signals that internal speech is unsafe, that policy critique is insubordination, and that silence is the only path to survival.

This is precisely what the First and Fourteenth Amendments were designed to prevent. A state actor that retaliates against protected speech or denies fair process to suppress criticism undermines the rights of the individual officer and the integrity of the public institution itself. In the NYPD, § 14-115 has become a legal instrument that converts protected expression into a punishable offense, without meaningful checks from courts, oversight bodies, or civilian review.

The Constitution demands more. Matthews and its predecessors make clear that internal discipline cannot be a safe harbor for unconstitutional conduct, even under the banner of “order” or “efficiency.” When § 14-115 punishes truth-telling, it becomes not a management tool, but a vehicle of repression, making it the law’s concern.

VII. Pattern and Practice: How Internal Policies Protect Abusers

Misusing Administrative Code § 14-115 does not happen in a vacuum. It is sustained by a broader internal infrastructure that insulates retaliatory decisions from scrutiny, cloaks reprisal in procedure, and ensures that accountability mechanisms serve the institution, not its members. Nowhere is this dynamic more visible than in the NYPD’s internal policy framework, including the widely publicized Administrative Guide 332-14, which purports to protect whistleblowers but in practice provides little meaningful shield.

A. AG 332-14: The Paper Shield

Adopted in the wake of rising public concern over retaliation and whistleblower suppression, Administrative Guide 332-14 establishes the NYPD’s internal policy against retaliation. It claims to protect employees from adverse action for making good faith reports of misconduct. But the guide has no enforcement teeth. It contains no independent investigatory mechanism, no oversight by an external authority, and no meaningful remedies for retaliation. The individuals accused of retaliation often remain in authority over the complainant.

Instead of serving as a deterrent, AG 332-14 functions as institutional theater—a gesture toward reform without actual structural change. Officers who invoke the policy in good faith often find themselves accused of “disrupting operations,” “undermining supervisory authority,” or “insubordination.” These characterizations then serve as predicates for § 14-115 disciplinary referrals, neutralizing the protections the policy claims to offer.

B. Internal Trials: Loyalty Over Legality

Departmental trials, overseen by the Deputy Commissioner of Trials and heard by Assistant Trial Commissioners, appear to offer procedural formality. But the underlying structure betrays the appearance of neutrality. These trial officers are appointed by, report to, and serve at the discretion of the Police Commissioner, who ultimately reviews and decides the disciplinary outcome.

Because there is no independent arbiter, retaliatory discipline can proceed unchallenged, so long as it is dressed in the language of order and efficiency. The trial process is not an adversarial proceeding in the constitutional sense but a validation mechanism. As long as some testimonial or documentary support exists—even if biased or pretextual—courts will almost always defer under Pell and similar administrative law standards. In practical terms, the trial system serves to sanitize retaliation, not to detect or deter it.

C. Deputy Commissioner of Legal Matters (DCLM): Legalizing Retaliation

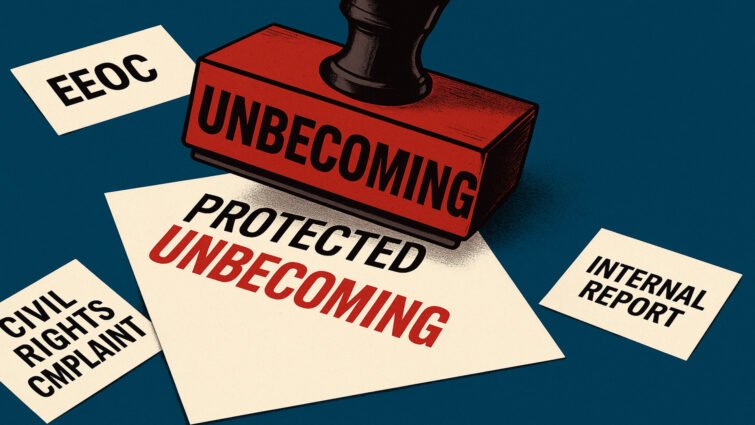

The Deputy Commissioner of Legal Matters (DCLM) is pivotal in legitimizing retaliatory discipline within the NYPD. Although the office presents itself as an internal check, tasked with reviewing disciplinary referrals for legal sufficiency, its function is often procedural, not protective. In practice, DCLM attorneys rarely challenge the substantive basis of § 14-115 charges, even when the underlying record is ambiguous, pretextual, or retaliatory.

DCLM’s review process routinely aligns with command-level priorities. Whistleblowers—particularly those who report racial discrimination, sexual harassment, payroll fraud, or constitutional violations—often find their protected activity reframed by DCLM as “poor judgment,” “insubordination,” or “disruption of command.” This linguistic laundering converts retaliation into legitimate-sounding infractions, ready for trial. The department then proceeds with confidence, knowing that its decisions are insulated behind a façade of legal vetting.

In a recent deposition, a former Deputy Commissioner of Legal Matters asserted that the office takes no part in the NYPD’s disciplinary process. According to this testimony, DCLM neither initiates nor manages disciplinary referrals and plays no substantive role in deciding whether charges should proceed under § 14-115. To date, there is no direct evidence to contradict that claim. However, when those same disciplinary actions are later challenged—whether through Article 78 petitions, EEOC charges, or civil rights lawsuits under Title VII, the NYSHRL, or NYCHRL—DCLM attorneys consistently vigorously defend the legitimacy of the underlying process, this pattern raises a critical question: if the office plays no role in discipline, why does it routinely shield those decisions in court? The answer lies in the structural role DCLM has come to occupy—not as an impartial observer, but as the legal defender of institutional retaliation, lending post hoc credibility to actions it claims not to control. In doing so, DCLM reinforces a system where retaliation is protected from scrutiny and publicly rationalized under the color of law.

This bureaucratic deflection creates a dangerous structural reality: no one is accountable. Investigative command initiates charges, the Department Advocate’s Office prosecutes them, and internal tribunals rubber-stamp them—all while courts defer and oversight bodies lack jurisdiction. The result is a closed loop where retaliation is framed, approved, and executed without ever triggering real scrutiny. DCLM becomes not a safeguard against abuse, but a critical link in its institutionalization.

D. Institutionalized Obstruction: No Path to Redress

Internal obstruction persists even when an officer attempts to fight back by filing with the EEOC, New York State Division of Human Rights (NYSDHR), or New York City Commission on Human Rights (NYCCHR). Departmental counsel may delay discovery responses, retaliate further through scheduling manipulation or reassignments, and resist conciliation despite substantial evidence.

Moreover, retaliated officers are often stripped of their reputation before their case can be heard. A negative psychological label, a publicized suspension, or inclusion on internal “monitoring” lists ensures that by the time a claim reaches an adjudicatory body, the officer’s credibility has already been eroded. This reputational damage is deliberate. It is part of a pattern and practice of organizational silencing.

E. The Culture Behind the Policy

These mechanisms—AG 332-14, internal trials, legal screening, and delay tactics—serve a common function: they protect abusers by punishing those who report them. When retaliation becomes bureaucratically enshrined and procedurally disguised, the institution no longer needs overt silencing tactics. It simply codes retaliation into its workflow.

This is why many NYPD officers choose silence over disclosure. They do not trust the internal system. They have seen what happens to colleagues who come forward. And they know that the currently structured law is unlikely to save them. In this way, the misuse of § 14-115 is not a legal flaw—it is a cultural feature, deeply embedded in an agency that has resisted meaningful external accountability for nearly two centuries.

VIII. Legislative and Judicial Remedies

If New York City Administrative Code § 14-115 is to serve its original purpose—maintaining good order and discipline—rather than functioning as a pretext for silencing dissent, legislative reform and judicial recalibration are urgently needed. The current legal structure enables abuse by design: concentrated disciplinary power, vague standards, internal adjudication, and broad judicial deference. These individually problematic features become constitutionally corrosive when deployed to punish protected activity.

A. Legislative Reform: Oversight, Definition, and Disclosure

1. Independent Oversight Before Referral

At a minimum, the City Council should amend § 14-115 to require review by an independent oversight body—such as the Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB) or Department of Investigation (DOI)—before any referral for “conduct unbecoming,” “neglect of duty,” or other catch-all categories can proceed. No NYPD executive should be allowed to initiate internal prosecution without external scrutiny, especially where protected activity is implicated.

2. Statutory Clarity and Safeguards for Protected Activity

The statute should be amended to define key terms—such as “immoral conduct” and “conduct prejudicial to good order”—and explicitly carve out exceptions for protected speech, association, and whistleblowing. These exclusions would codify constitutional protections into the disciplinary process and limit opportunistic reinterpretation of protected conduct.

3. Transparency and Public Reporting

The City should require mandatory public reporting on all § 14-115 referrals, disaggregated by type of charge, demographics, and outcome. This would allow independent researchers, journalists, and civil rights advocates to monitor for patterns of abuse and disparate impact. Like police stops or use of force data, internal disciplinary referrals can—and should—be tracked as a form of public accountability.

B. Judicial Reform: Challenging Deference and Opening the Record

1. Reassessing Judicial Deference Under Pell

The Matter of Pell framework, which permits courts to uphold agency discipline unless it is “shocking to one’s sense of fairness,” grants excessive leeway to agencies with documented patterns of abuse. Courts reviewing § 14-115 referrals should tighten the standard where retaliation is plausibly alleged, particularly when vague charges are brought after protected activity.

2. Younger and Rooker-Feldman Doctrines: Carve-Out for Retaliation Claims

Federal courts often abstain from hearing constitutional claims involving internal discipline under doctrines like Younger v. Harris and Rooker-Feldman. But these abstention doctrines should yield when § 14-115 is used to retaliate against whistleblowers. Courts must recognize that retaliation cloaked in procedural legitimacy is still unconstitutional, and refusal to intervene effectively denies plaintiffs a forum.

3. Presumptive Discovery and Preliminary Injunctions

Litigants challenging § 14-115 discipline as retaliatory should be afforded presumptive access to discovery, including communications among command staff, investigators, prosecutors, and the DCT. Where credible retaliation is alleged, courts should be empowered to grant preliminary injunctions to halt pending disciplinary actions until judicial review is complete. Otherwise, retaliated officers suffer irreversible harm—reputational, emotional, and financial—before their case is even heard.

C. Whistleblower Protection Integration

City and state whistleblower laws must be amended to create explicit immunity from § 14-115 discipline for officers who engage in protected activity, including filing complaints, testifying in legal proceedings, or opposing unlawful practices. These protections should include:

Right to independent investigation of any § 14-115 charges within one year of protected activity;

Rebuttable presumption of retaliation for charges filed within a defined proximity to whistleblowing;

Civil penalties and personal liability for investigating officers and other personnel who misuse the statute to suppress dissent.

These reforms must be codified, not policy-based, to prevent circumvention by new leadership or administrative reinterpretation.

D. City Charter and Civil Service Reform

Ultimately, the authority granted to the Police Commissioner under § 14-115 must be rebalanced. One solution is to limit final disciplinary authority in whistleblower-related cases through Charter reform, vesting final review in an independent public safety board. This board should include civil rights experts, retired judges, and community representatives, not just former law enforcement executives.

Civil service rules should also be revised to prohibit “dual-track retaliation,” in which officers face simultaneous psychological referrals, internal trials, and performance scrutiny after reporting misconduct. When multiple adverse mechanisms converge, courts and arbitrators must view them not in isolation, but as a pattern of retaliatory intent.

The legal system cannot afford to treat retaliation by public institutions as a private employment dispute. When § 14-115 is used to suppress constitutionally protected speech, it ceases to be a disciplinary tool and becomes a vehicle of state-sponsored coercion. It is time for lawmakers and judges alike to confront that reality—and legislate, interpret, and rule accordingly.

IX. Conclusion: The Duty to Dissent

In a democratic society, the line between order and oppression is drawn not by the presence of rules, but by how power is exercised in their name. Administrative Code § 14-115 was never meant to be a silencing statute, yet in the NYPD, it has become just that—a blunt disciplinary instrument used not to promote integrity, but to eliminate dissent.

When an officer challenges a quota system, reports racial discrimination, exposes sexual misconduct, or testifies truthfully in a civil rights lawsuit, they are not breaking the chain of command. They are fulfilling a higher oath—to the Constitution, not the Commissioner. And yet, time and again, the department responds not with introspection, but with reprisal. Behind a curtain of internal procedures and legal abstractions, § 14-115 has been twisted into a mechanism of control, ensuring that the voices most needed in reform are the first to be punished.

This is not just a policy failure—it is a failure of law. Courts defer. Oversight bodies remain sidelined. The public is left in the dark. And inside One Police Plaza, retaliation remains the safest bet for preserving power. The structural abuse of § 14-115 reveals a painful truth: retaliation is not an aberration within the NYPD. It is operational doctrine.

But it doesn’t have to be. The tools to dismantle this system already exist: legislative reform, judicial intervention, and collective civic pressure. What’s missing is the will to use them. Protecting whistleblowers—especially those inside law enforcement—is not merely a policy preference. It is a constitutional necessity. If we want a police force that serves the public rather than protects itself, we must build legal frameworks that protect those who speak the truth from within.

The duty to dissent is the foundation of all civil rights progress. When the law is used to crush that dissent, it is not just the whistleblower who suffers—the public trust, the rule of law, and the legitimacy of our institutions. Section 14-115 may remain on the books, but how we interpret, amend, and enforce it will determine whether we live in a city governed by principles—or by power alone.