Introduction: A Culture Older Than the Badge

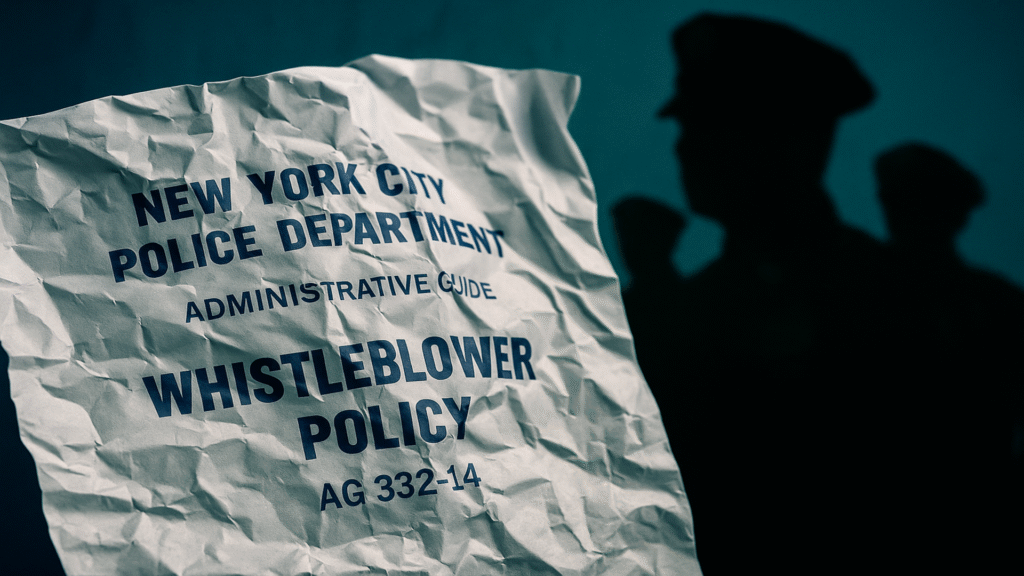

The NYPD’s whistleblower policy—codified in Administrative Guide Procedure AG 332-14—appears to reflect modern ideals of accountability, transparency, and institutional self-correction. The rule affirms that members who report corruption, misconduct, or policy violations are entitled to protection from retaliation. But this policy, like so many procedural reforms before it, functions not as a shield but as a screen—one that obscures a more profound, more insidious institutional truth: the NYPD’s culture is not designed to protect dissent. It is designed to erase it.

To understand why whistleblowers continue to face retaliation despite formal protections, we must go beyond contemporary policy language and confront the historical structure of American policing—and New York’s in particular. The NYPD, officially established in 1845, did not emerge in a vacuum. It inherited the DNA of colonial social control systems that were never designed to accommodate internal dissent. From the Dutch rattlewatch of the 1600s to the English-appointed constables and night watchmen of the 1700s, early policing in New York was rooted in protecting mercantile interests, surveilling the laboring classes, and suppressing unrest, not ensuring equity or transparency.

These proto-police forces were not neutral agents of public safety. They were politically appointed, often corrupt, and intimately tied to local power brokers. Their operations prioritized loyalty over legality, silence over scrutiny, and obedience over conscience. Officers who defied political masters or challenged abusive practices were removed, not rewarded. There was no infrastructure for principled objection—only systems of control that served the dominant order. In this context, retaliation was not an aberration. It was enforcement.

That foundational logic carried directly into the professionalization of the NYPD. When New York City adopted the London policing model in 1845, it imported the trappings of reform—uniforms, discipline, hierarchy—but left intact the control mechanisms. The department remained politically entangled, internally opaque, and ideologically hostile to dissent. And while modern labor laws, civil rights statutes, and whistleblower protections have since emerged, they have been layered atop, not woven into, the department’s organizational core.

What results is a two-tiered system: a public-facing framework of rules and rights, and a subterranean culture of suppression that undermines them. Whistleblowers today find themselves in the same position as truth-tellers centuries ago—accused of disloyalty, subjected to isolation, and disciplined not for falsehoods but for speaking truths the institution cannot tolerate. AG 332-14 offers procedural cover for a department that has, since its inception, valued silence as a condition of service. The policy is not a remedy for retaliation—it is evidence of its normalization.

This article traces the normalization from the 17th century to the present. It situates modern whistleblower policy in a centuries-long pattern of institutional resistance to internal scrutiny. It also argues that no policy—even one as well-meaning as AG 332-14—can succeed without dismantling the retaliatory culture it seeks to regulate. Until that culture is confronted at its structural roots, whistleblowing will remain an occupational hazard—and silence, once again, will be the safest sound inside One Police Plaza.

I. From Rattlewatch to Retaliation: The Historical Logic of Institutional Silence

Long before the NYPD’s modern oath, administrative guide, or blue wall, there were the rattlewatchers. In 1658, when New Amsterdam was still under Dutch control, these night watchmen patrolled the streets carrying wooden rattles to summon help or signal danger. However, their purpose was not to protect individual liberty or ensure public transparency. Like their successors, their role was to enforce order for those in power—namely, the colonial merchants, property owners, and political elite.

That function did not change with the British conquest in 1664. Colonial constables and watchmen continued to serve at the discretion of local authorities, their accountability not to the public, but to governors, magistrates, and municipal power structures. Early New York law enforcement was explicitly designed to suppress “unlawful assemblies,” monitor dissent, and enforce moral discipline, not to investigate internal corruption or promote public integrity. There were no protections for officers who challenged political favoritism or reported misconduct. To speak out was to invite removal, banishment, or worse.

Even after American independence, New York’s approach to policing retained these control mechanisms. Law enforcement’s professionalization did not dismantle political patronage or internal coercion systems—it refined them. By the 1820s, the city’s watch system was rife with corruption and favoritism. Patrolmen purchased appointments or owed allegiance to local ward leaders, prioritizing political loyalty over competence or ethics. A whistleblower in such a system had no avenue for redress—only risk.

The NYPD’s formal creation in 1845 did little to change this reality. While modeled after Sir Robert Peel’s London Metropolitan Police, the NYPD immediately became an arm of Tammany Hall politics, where promotions, assignments, and even arrests could hinge on political allegiances. Officers were punished not for corruption, but for disobedience of power. The department’s historical submission to the U.S. Department of Justice openly acknowledges this: early disciplinary actions disproportionately targeted those who defied internal hierarchies, not those who violated law or ethics.

Internal criticism was never welcomed. Those who raised alarms about bribery, extortion, or brutality were ignored or removed. As the NYPD expanded and modernized in the 20th century—introducing training academies, civil service exams, and internal review boards—the underlying cultural logic persisted: internal loyalty outweighed public accountability. Whether under Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt or during the post-WWII expansion, officers who challenged the system remained suspect. The 1970s Knapp Commission hearings confirmed what many already knew—that whistleblowers like Frank Serpico were more endangered by their departments than by the criminals they pursued.

The department’s DOJ-submitted history confirms that efforts to reform internal practices have repeatedly faltered because they failed to address this cultural root. Technological innovations (like CompStat), managerial reorganizations, and community engagement models did little to dismantle the internal message passed down for generations: speak out, and you’re out.

In this context, Administrative Guide Procedure AG 332-14 reads less like a safeguard and more like a disclaimer. It exists in a department whose earliest origins taught silence as a virtue and retaliation as routine. Unless the culture from those origins is confronted, policies like AG 332-14 will remain what they have always been—text on paper in an institution built on erasure.

II. AG 332-14: Policy in Print, Retaliation in Practice

At first glance, Administrative Guide Procedure AG 332-14 suggests a department committed to integrity and internal accountability. The procedure prohibits retaliation against members reporting misconduct, fraud, corruption, or other wrongdoing. It even outlines protections for those cooperating with investigations and protocols for handling complaints through confidential channels. But in reality, the document operates less as a shield and more as institutional theater—crafted for compliance optics, not internal empowerment.

The gap between policy and practice is not a matter of oversight. It is a deliberate function of the NYPD’s operational structure. The chain of command within the department is not merely a reporting structure—it is a culture of unquestioned obedience. This has profound implications for whistleblower protections. AG 332-14 requires that complaints be routed through department-approved channels—Internal Affairs, legal bureau staff, or superior officers. Yet these very entities often have ties to the same leadership implicated in the misconduct, creating an ecosystem where loyalty is rewarded and dissent is punished under the guise of “performance,” “fitness,” or “conduct unbecoming.”

Even more problematic is the total lack of independence in investigating retaliation claims. The same command structures that oversee an officer’s performance, assignment, and disciplinary record often control the internal complaint pathways. The result is a chilling procedural paradox: a whistleblower must report retaliation to those who may have authorized or participated in it.

Numerous high-profile cases illustrate this institutional absurdity. Officers who reported sexual harassment, racial discrimination, or command misconduct were subjected to retaliatory transfers, psychological referrals, Internal Affairs scrutiny, and time-and-leave audits. On paper, these adverse actions were rarely linked to the original complaint. Instead, the machinery of retaliation operated through bureaucratic proxies: unannounced audits, denied overtime, negative performance notations, or suspensions cloaked in administrative language. When the employee connected the dots, the department had papered over the retaliation as routine supervision.

The predecessor to AG 332-14 was in effect during a period when then-Lieutenant Quathisha Epps made repeated internal disclosures about sexual assault, quid pro quo harassment, and widespread executive misconduct within the NYPD. Yet, rather than shield her from retaliation, the Department’s policies enabled it. On December 18, 2024—just days before she filed her EEOC complaint and publicly disclosed being sexually assaulted by then–Chief of Department Jeffrey B. Maddrey inside NYPD Headquarters—Ms. Epps was abruptly suspended from duty. That suspension was orchestrated not by an independent body, but by Maddrey’s close ally, retired Chief of Internal Affairs Miguel Iglesias, who used his internal influence to neutralize Epps as a threat. Commissioner Jessica Tisch, legally empowered under the New York City Charter and New York City Administrative Code § 14-115 to intervene, allowed the machinery of retaliation to proceed unchecked. Whether through direct coordination or deliberate inaction, Tisch enabled a departmental response that punished the victim while shielding the abuser.

Following her forced retirement in early 2025, the Department escalated its retaliation by demanding that Epps repay $231,896.75 in alleged overtime “overpayments.” Issued by Director Viktoria Denysenko on April 22, 2025, this collection demand came without legal justification, audit documentation, or proof of misconduct. It stood in stark contrast to the Department’s long history of tolerating administrative irregularities among high overtime earners. The NYPD failed to meet its obligations under New York Labor Law § 195(4) and 12 NYCRR § 142-2.6, which require employers, not employees, to maintain accurate payroll records. Under that legal framework, any uncertainty caused by deficient documentation must be resolved in the employee’s favor. Instead, the Department reversed the burden and accused a whistleblower of fraud without evidence, an audit, or due process. The collection demand—unprecedented in scope and timing—functioned not as a legitimate recovery action but as a retaliatory measure designed to discredit Epps and deter future disclosures. It rendered the NYPD’s internal whistleblower protections hollow, exposing them for what they are: policy shields that collapse when power is threatened.

This structural failure is an implementation problem and an existential indictment of the policy’s validity. A proper whistleblower protection framework requires independence, transparency, and credible enforcement. AG 332-14 provides none. It fails to insulate complainants from their command, offers no recourse beyond internal channels, and does not publicly disclose retaliation statistics or outcomes. Worse, it allows retaliatory actors to participate in the investigative process, thereby legitimizing retribution under the veneer of process.

As submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice, the NYPD’s published history acknowledges that cultural and systemic resistance to internal accountability has plagued the department since its inception. From the political purges of the 19th century to the blue wall of silence that shielded corruption in the 20th, the department has always treated internal critics as destabilizing forces. AG 332-14 has done little to disrupt that legacy.

The policy functions more as an institutional firewall, invoked when necessary to defend the department in litigation, but rarely activated to protect the individual who risks everything by coming forward. The department can point to the policy and say, “We have protections.” But ask a whistleblower whether those protections function, and you will hear a different story: a procedural maze designed to exhaust, isolate, and ultimately erase.

In this light, AG 332-14 is not a failure of drafting—it is a failure of institutional will—a fig leaf policy in a fortress department. And until the structure that punishes truth-telling is dismantled, no number of procedures will protect those who speak out. They will continue to face the same fate their predecessors did—marginalized, retaliated against, and remembered only in lawsuits and headlines.

III. New Tools, Old Tactics: How CRAFT, Psychological Referrals, Drug Testing, and Integrity Tests Silence Dissent

While the NYPD continues to modernize its infrastructure—rolling out tools like CRAFT, upgrading performance reviews, and expanding digital oversight—these advancements have done little to alter the department’s entrenched culture of silencing dissent. On paper, systems like the Cop Rapid Assessment Feedback Tool (CRAFT), psychological referrals, and random drug testing are touted as professionalization efforts. In practice, they frequently function as retaliatory levers—deployed disproportionately against officers who speak out, challenge misconduct, or disrupt the internal chain of command.

CRAFT, for instance, was introduced as a performance optimization tool—allowing officers to self-report daily activities, and enabling supervisors across commands to input feedback in real time. Supervisors now conduct monthly assessments and quarterly evaluations using CRAFT’s data streams. However, rather than promote transparency, CRAFT has, in numerous instances, become a tool for targeted surveillance. Officers engaged in protected activity—filing complaints, raising ethical concerns, or being viewed as disruptive—find themselves flagged repeatedly, their performance downgraded through vague or selectively applied metrics that can later justify discipline, denial of promotion, or reassignment.

Psychological referrals are another longstanding tactic repackaged in bureaucratic legitimacy. Ostensibly framed as tools for officer wellness and public safety, these referrals have frequently been weaponized to marginalize whistleblowers and officers deemed politically inconvenient. Rather than responding to psychological distress or misconduct, referrals are often initiated after an officer raises internal complaints, challenges senior leadership, or disrupts the unspoken norms of loyalty within the chain of command. The process can sideline the employee from active duty, cast doubt on their credibility, and pave the way for forced retirement, often without any prior disciplinary record, formal evaluation concerns, or due process protections. In this way, psychological referrals serve less as a safeguard for the department and more as a bureaucratic mechanism to eliminate dissenters under the guise of mental health screening.

So-called “random” drug testing likewise fails to live up to its name. Officers known to be under internal scrutiny or politically inconvenient often find themselves selected “at random” or “for cause” shortly after making protected disclosures or clashing with leadership. While nominally routine, these tests have been used to suspend officers without due process, particularly where the testing procedures are opaque, rely on flawed methodologies (such as hair testing with disputed reliability), or target only certain demographic groups.

Integrity tests are another longstanding tactic repackaged in bureaucratic legitimacy. Officially described as tools to promote ethical conduct and root out misconduct, they are frequently weaponized against employees viewed as internal threats. Under the pretext of oversight, investigative units stage deceptive scenarios—planted cash, fake bribes, or contrived violations—intended to provoke a response from unsuspecting officers. These tests are rarely random. They are selectively deployed, often following protected activity, dissent, or whistleblowing, and serve more as a trap than a tool. Regardless of outcome, the test becomes part of the officer’s shadow record—used to justify suspicion, initiate surveillance, or rationalize adverse employment actions. The message is clear: challenge the institution, and the institution will challenge your integrity.

These tools—CRAFT, psychological evaluations, drug and integrity testing—are not inherently problematic. But when wielded within a structure that has historically punished whistleblowers, they become instruments of institutional suppression. Their modern veneer should not obscure their continuity with older, more overt forms of control.

The Department’s internal justification may cite performance, integrity, or accountability. However, if viewed in a historical context—and through the lived experiences of officers like Epps—the pattern is clear: the NYPD has refined its methods of reprisal. The silencing continues, just with better software.

IV. Policy Without Power: Why Whistleblower Protections Fail in Practice

On its face, Administrative Guide Procedure AG 332-14 promises meaningful protection: a formal declaration that members of the service may report corruption, misconduct, and unlawful behavior without fear of retaliation. But in practice, this policy offers little more than procedural theater—reciting principles it has no intention of enforcing. The protections are limited, discretionary, and structurally subordinated to the chain of command to which a whistleblower must often report. The designated intake mechanism, the Internal Affairs Bureau (IAB), is not independent. It is a unit within the NYPD, governed by the same promotional hierarchies, cultural pressures, and political dynamics that whistleblower complaints often implicate. This renders the process circular at best, retaliatory at worst.

AG 332-14 also lacks binding enforcement provisions. There is no guaranteed anonymity, no timeline for resolution, no public reporting requirement, and no consequence for officers who retaliate against violating its provisions. Worse, the policy explicitly allows the Department to “reassign” or “monitor” complainants—language that, in practice, has been used to justify involuntary transfers, changes in assignment, psychological referrals, or prolonged sidelining without cause. These tactical forms of retaliation are rarely documented, giving leadership plausible deniability while sending a clear institutional message: you are no longer trusted.

This structural failure is compounded by the Department’s internal legal culture, which treats whistleblower allegations not as opportunities for reform but as threats to operational control. Legal counsel, risk management personnel, and executive command often act in concert, not to evaluate the merits of the report, but to assess the risk exposure of leadership. The result is predictable: retaliation becomes a risk management tool, used to contain the spread of legal liability by discrediting the source.

The Department’s refusal to apply AG 332-14 to cases involving senior officials is even more troubling. In such cases, the command structure is so tightly intertwined with the subject of the complaint that whistleblower protections all but collapse. The process becomes inverted: the Department scrutinizes the accuser instead of investigating the accused. Time records are audited. Disciplinary history is reexamined. Prior evaluations are revisited for negative performance markers that can be retrofitted into a justification for punishment.

This systemic reversal, where the whistleblower becomes the target, is not a flaw in the policy. It is a feature of the institution that created it. AG 332-14 is not designed to protect truth-tellers but to shield the Department from legal exposure while projecting an image of accountability. It allows the NYPD to claim reform while preserving the coercive suppression tools.

In short, the realities of organizational culture, command loyalty, and legal risk aversion undermine the whistleblower protections on paper. Until the power to investigate misconduct is transferred to an entity truly independent of NYPD command, no policy—however well worded—can serve its intended purpose. The protections are illusory because the system is designed to protect itself.

V. Patterns, Not Outliers: How Selective Enforcement Reflects Systemic Intent

What emerges from the NYPD’s disciplinary practices is not a series of isolated abuses but a coherent pattern in which institutional tools are repurposed to protect the powerful and punish the disobedient. By the time an officer is targeted with a drug test, flagged in CRAFT, referred for psychological evaluation, or baited in an integrity test, the outcome has already been shaped not by due process, but by departmental politics.

Despite the internal pretense of fairness, the NYPD has long operated on a principle of discretionary control: the chain of command determines what rules are broken and who will be held accountable. In that context, enforcement becomes a form of messaging—used less to address misconduct than to communicate internal boundaries of power and allegiance.

Supervisors understand this calculus. So do rank-and-file officers. Everyone learns quickly that the rulebook is not the rule. Loyalty is the rule. Silence is the rule. Deviate from that unwritten code—especially to report misconduct, expose harassment, or challenge senior leadership—and the formal policies meant to protect you become irrelevant.

That’s why AG 332-14, like its predecessors, rings hollow. It may look like whistleblower protection. It may cite compliance language. However, in the ecosystem of NYPD discipline, where data can be manipulated and accusations selectively deployed, protections are only as strong as the institution’s willingness to enforce them impartially.

And that willingness has never truly existed.

This is why cases like Epps matter—not only for their legal implications but also for what they reveal about the department’s structural DNA. When whistleblowers are met with sudden audits, false fraud claims, and public smears—when long-tolerated practices are reframed as criminal only after protected disclosures—the message is unmistakable: truth-telling is treason.

That message reverberates through the ranks. It discourages not only formal complaints but also informal checks on power. It creates a culture where retaliation is anticipated, protections are distrusted, and accountability is seen not as a right, but as a liability.

The problem is not bad actors. The problem is a system designed to protect bad actors and punish their challengers. Until that design is confronted head-on—through transparent enforcement, independent oversight, and statutory mandates that strip discretion from the chain of command—no amount of procedural reform will make whistleblowing safe.

In the NYPD, retaliation is not the exception. It’s the enforcement model. And until that model is broken, policies like AG 332-14 will remain what they’ve always been: paper shields in an armored institution.

VI. Conclusion: Retaliation Is Policy Until Oversight Has Power

Administrative Guide Procedure AG 332-14 is not a failure of intent. It is a failure of power. As long as whistleblower complaints remain embedded within the same NYPD command structure they often implicate, retaliation will not just persist—it will thrive under procedural camouflage.

The NYPD’s internal system is incapable of policing itself. That much has been clear since its inception. What is needed is not another internal review mechanism or aspirational language about integrity. What is required is civilian oversight with real teeth, structural independence, and the legal authority to confront retaliation head-on.

New York City already possesses the institutional infrastructure to fulfill this role: the Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB). However, its current jurisdiction and authority are insufficient to meet the scope and complexity of whistleblower retaliation within the NYPD. To make AG 332-14 more than a paper shield, the City must expand and reform the CCRB’s mandate, turning it into a meaningful engine of police accountability that includes protection for whistleblowers and internal dissenters.

This means:

Expanding the CCRB’s jurisdiction to include complaints of retaliation and whistleblower suppression, particularly where the complainant has alleged sexual harassment, discrimination, or executive misconduct.

Strengthening investigative authority by reducing dependency on the NYPD for documentation access and replacing the current MOU with a binding, enforceable agreement that mandates timely disclosure of records, disciplinary files, and command-level communications.

Revising City legislation to authorize the CCRB to conduct full-scale retaliation investigations, independent of Internal Affairs, with the ability to subpoena witnesses, compel production of evidence, and issue findings directly to the Police Commissioner and the public.

Enhancing prosecutorial authority by allowing CCRB’s Administrative Prosecution Unit to bring charges in all substantiated cases of whistleblower retaliation—even when they implicate high-ranking officials—and limiting the Police Commissioner’s discretion to override disciplinary recommendations without written, public justification.

Mandating public reporting of retaliation complaints and outcomes, including statistical breakdowns by command, rank, and protected activity involved, as part of the City’s broader civil rights data transparency initiative.

With over 140 civilian investigators and a dedicated administrative, legal, and mediation infrastructure, the CCRB is uniquely positioned to absorb this role if given legislative support. By transforming the CCRB into a centralized whistleblower protection and accountability body, New York City can demonstrate that oversight is a symbolic gesture and a structural commitment.

Retaliation in the NYPD is not an aberration. It is the legacy of a department whose roots were planted in political loyalty and organizational silence. Every policy reform that ignores that truth is destined to fail.

Until the power to investigate, prosecute, and expose retaliation is removed from the NYPD’s internal command and placed in the hands of a strengthened CCRB, whistleblowing will remain the most dangerous act an officer can commit. And AG 332-14 will remain what it has always been: a fragile promise inside an armored institution.

Proper accountability requires more than procedure. It requires power, and it is time the City gave it to those willing to use it.

Call to Action

The time for symbolic oversight has passed. If New York City is serious about protecting those who risk their careers and safety to expose corruption and abuse, it must act decisively. The Civilian Complaint Review Board must be more than a civilian buffer; it must become a fully empowered investigative and prosecutorial body, capable of intervening when the chain of command becomes a weapon of suppression.

City Council must legislate expanded jurisdiction, binding disclosure authority, and independent prosecutorial discretion for the CCRB in all cases involving whistleblower retaliation, particularly where allegations implicate high-ranking officials or expose systemic misconduct. The Memorandum of Understanding that governs the CCRB’s authority must be replaced with enforceable mandates, and the agency’s findings must be made public—no more buried reports, no more confidential sidesteps, no more impunity.

Silence inside the NYPD has never been accidental. It is historical. It is structural. And unless the City equips oversight agencies with the power to break that silence, every promise of reform will ring hollow. The badge may be old, but the excuse of helplessness is older.

The question now is not whether the City can act. It’s whether it will.