I. Introduction: Recycled Strategies from a Corrupt Blueprint

Every time the NYPD rolls out a new public safety campaign, the political class pretends it’s progress. “Park, Walk and Talk.” “Neighborhood Safety Teams.” “Community Policing.” “Precision Deployment.” Different names. Same result. The same institution, drawing from the exact foundational blueprint, insists that this time will be different, while everything from the arrest data to the civil rights lawsuits proves otherwise.

The hard truth they won’t say at the press conference: no amount of rebranding can rehabilitate an institution that was never built for justice in the first place.

Policing in America didn’t evolve out of some neutral need to protect the public. As a matter of design, it was created to enforce social control on behalf of the powerful. Whether through slave patrols in the South, strike-breaking in the North, or curfews in Dutch colonial outposts, early American policing was never about reducing harm or building community. It was about safeguarding capital, enforcing racial and economic hierarchies, and suppressing dissent. That original mandate never disappeared. It was bureaucratized, professionalized, and rebranded but never dismantled.

So when politicians and police executives promise to “restore public trust” with a new rollout of enforcement teams or community liaison officers, they’re reviving a failed strategy from a corrupt playbook. It’s a cycle of self-preservation, not public protection.

And while the talking points may change, the tactics remain hauntingly familiar: saturation patrols in Black and Brown neighborhoods, arbitrary stop-and-frisk encounters. Discretion was revoked from officers in favor of quota-driven enforcement—data manipulated to show impact while communities bear the brunt of arrests, court dates, and trauma.

Let’s be even more specific. When NYPD brass push officers to meet “performance goals” by flooding specific neighborhoods with bike summonses or conducting stop-after-stop in high-poverty ZIP codes, they’re not fighting crime—they’re manufacturing stats to justify their existence. It’s the illusion of safety masquerading as strategy. And when it backfires—as it always does—the rank-and-file officers are left holding the bag, while the top brass and their political patrons deny responsibility and redirect the spotlight.

We’ve seen this before. During the height of Stop, Question, and Frisk, NYPD officers were given unofficial quotas, rewarded for volume, and punished for discretion. Tens of thousands of Black and Latino men were stopped, searched, and humiliated—not because they posed any threat, but because the system demanded bodies, not outcomes. And when the litigation came—Floyd v. City of New York—the department’s leadership insisted the officers had “discretion” the whole time.

That’s the pattern: manufacture the crisis, misapply the cure, and scapegoat the lowest-ranking actor in the chain when the consequences come.

The result is predictable: communities lose faith, officers lose morale, and the public is left asking why nothing changes except the slogans.

Here’s the reason: you can’t reform an institution out of its original purpose without first confronting that purpose. And the purpose of American policing, from its inception, was not to nurture safety—it was to enforce order on terms defined by property owners, politicians, and elites.

So, when we talk about “crime” and “safety” today, we start from a false frame. The more urgent question isn’t how to improve policing. The real question is: Why are we still expecting policing to do what it was never built to accomplish?

Crime is not just a symptom of lawlessness—it’s often a product of disinvestment. Of generational poverty. Of systemic neglect. Of broken schools, inaccessible healthcare, evictions, untreated trauma, and entire neighborhoods that have been economically redlined and politically discarded.

Policing doesn’t solve that. Policing punishes that.

And that’s the story we must tell—because the institutions won’t. This long-form essay will trace the architecture of American policing from the Dutch rattle watch to slave patrols, from political patronage to racial surveillance, from war-on-drugs militarization to performance-driven enforcement, not as a disconnected series of failures but as a continuous design.

If we’re serious about public safety, we must stop presenting old forms of control as new solutions. We must stop asking an institution born of corruption to solve the conditions it was built to manage, not fix.

We start by telling the truth.

II. Colonial Foundations: The Rattle Watch and the Architecture of Control

To understand why policing in New York City functions as a mechanism of control rather than protection, you must start where the city began—not with Sir Robert Peel’s “principles of policing,” not with the Constitution, but with the Dutch West India Company. This profit-hungry multinational trading corporation founded New Amsterdam on stolen Lenape land.

In the 1600s, the purpose of the settlement wasn’t democracy. It was commerce. The city wasn’t built for the people who lived in it—it was constructed to serve the commercial ambitions of a private corporation that trafficked in furs, sugar, enslaved Africans, and imperial competition. Law enforcement, such as it was, existed to stabilize markets, suppress dissent, and regulate labor. These weren’t abstractions. These were policies. And the enforcers of those policies were the rattle watch—a primitive patrol unit made up of appointed men who roamed the streets at night, sounding wooden rattles to announce their presence or summon backup.

That was the city’s first formal policing body, and its mission wasn’t justice—it was discipline.

The rattle watch enforced curfews, monitored suspicious gatherings, controlled the movement of laborers, and surveilled any behavior deemed inconsistent with the colony’s economic goals. They patrolled the margins of a society organized around inequality. They weren’t protecting the community—they were protecting the company from the community.

This distinction is foundational. From the start, the logic of policing in what would become New York City was top-down. The ruling elite’s interests—first a commercial corporation, then colonial governors, and later property-owning white men—were imposed on the population through the visible presence of a body empowered to enforce order by any means necessary.

It is a grave mistake to describe this as the “infancy” of modern policing, as though it were a clumsy but well-intentioned precursor to something more principled. The rattle watch did not evolve into community-based law enforcement. It was a prototypical model of economic surveillance, and its institutional DNA—monitor, control, deter—still governs police operations today.

Just as telling is the structure of their authority: The Rattle Watch was not democratically accountable. Colonial officials made their appointments, and their function was not to mediate disputes between citizens but to enforce preemptive order. The poor, the indentured, the disorderly were the threats to be managed, not necessarily because they posed a danger, but a risk to the city’s commercial viability.

That’s the quiet truth buried beneath the mythology of policing: from its earliest days, it has always been as much about what must be prevented as what must be punished. The mere existence of marginalized populations—untethered from wealth, unregulated by institutions, unrooted from property—has always been framed as a latent danger to the status quo. The role of the enforcer is to render that danger visible, manageable, and suppressible.

The rattle watch was designed to do exactly that.

Fast-forward nearly four centuries, and the logic hasn’t changed. Whether broken windows, stop-and-frisk, or so-called “precision policing,” the same principles endure: saturate “problem areas,” demonstrate presence, disrupt potential disorder, and signal command authority. The tools are new—guns, radios, patrol cars, data dashboards—but the goals are not. The target is still behavioral noncompliance. The purpose is still to stabilize the city for those who control its resources.

Even the language echoes across time. What the Dutch called “order,” modern mayors call “quality of life.” What the rattle watch suppressed through curfews and nighttime surveillance, today’s NYPD polices through sidewalk summonses, subway checks, and the daily harassment of Black and Brown youth under the guise of community safety.

And let’s not forget: in 1658, less than 30 years after the founding of the city, Black people—enslaved and free—comprised over 20% of New Amsterdam’s population. The rattle watch didn’t just emerge to control labor—it emerged in a racialized context of forced servitude, surveillance, and state-sanctioned economic extraction. That too is part of the story: policing was forged in a colonial setting where racial caste, corporate dominance, and violent order were normalized, and that formation has never been fully dislodged.

What’s more dangerous than a corrupt system is one whose corruption is mistaken for neutrality. And the rattle watch, for all its archaic imagery, is not a relic—it’s a blueprint. It shows us that from the start, policing in New York was designed not to serve communities, but to discipline them into obedience under a model of governance that privileged commerce, whiteness, and hierarchy.

The modern NYPD was not built from scratch. It was built from this. Layer by layer, brick by brick, the department inherited the logic of its colonial forebears: treat disorder as a threat, define the marginalized as potential enemies, and deploy uniformed bodies to keep them in check.

If you want to understand the failure of policing to deliver public safety today, look at what it was created to deliver in 1650: silence, not justice—obedience, not safety.

This was not a misfire. This was a mission.

III. Slave Patrols: Policing as Racial Domination, Legal Infrastructure, and Economic Enforcement

If New York’s rattle watch was the prototype for commercial surveillance in urban colonies, the slave patrol was the blueprint for racialized, militarized policing in the American South. It didn’t emerge in response to lawlessness. It wasn’t formed to protect communities. It was crafted from the ground up to enforce a racial economic order, to preserve wealth through violence, and to render Black autonomy a criminal threat to be neutralized by force.

This is not a metaphor. This is institutional history.

Slave patrols were codified in law. By 1704, South Carolina had passed formal statutes requiring white men to serve on patrols that operated under the direct authority of local governments. They were empowered—obligated—to search Black homes, question any Black person they encountered, administer corporal punishment without trial, and detain or kill those they deemed “runaways” or “rebellious.”

Patrol laws mandated routes, armed supervision, nighttime surveillance, and even reward systems for “recovering property”—language that referred to human beings. There were fines for non-participation. Incentives for capture. Immunity for violence. And no pretense of impartiality. These patrols were the state’s answer to a central problem in a slaveholding economy: how do you contain the people whose labor your wealth depends on, when those same people have every reason to escape, resist, and rebel?

The answer: legalize terror.

Slave patrols didn’t just exist to retrieve those who fled. They were designed to make escape, resistance, and dignity impossible. Their function was psychological as much as physical—to make surveillance constant, punishment arbitrary, and freedom unthinkable. They reinforced the idea that Black people were not citizens, not persons under the law, but property to be surveilled, corrected, and subordinated.

And when slavery was abolished, that logic didn’t vanish. It adapted.

In the years after the Civil War, Southern legislatures scrambled to restore the plantation economy under a different name. The solution: the Black Codes—a patchwork of local and state laws that made it a crime for Black people to be idle, unemployed, homeless, loud, defiant, or disobedient. “Vagrancy” became a catchall charge to round up freed people en masse. “Loitering” and “insubordination” became legal fictions to justify arrests. And who enforced these laws? The same men who had run the slave patrols—now repurposed as sheriffs, constables, and the first uniformed police in Southern towns.

These officers didn’t patrol to serve communities—they patrolled to harvest bodies for forced labor, feeding the exploding convict leasing system that turned jails and prisons into supply lines for white landowners, coal mines, railroads, and textile mills. It wasn’t abolition. It was a rebranding.

Under convict leasing, state and county governments profited by renting out Black prisoners to private companies under brutal, lethal conditions. Arrests became an economic strategy. Enforcement became production. In Alabama, between 1875 and 1900, over 90% of leased convicts were Black. In some counties, leasing revenues exceeded the total cost of law enforcement, turning police into brokers for human labor and brutality.

This is not incidental to the history of policing—it is the history.

The patrol didn’t die with the Civil War. It put on a badge.

It trained its weapon not just on those who defied slavery, but on those who defied the economic silence slavery demanded. And the badge didn’t make policing more lawful—it made it more permanent. More bureaucratic. More sanitized. It institutionalized a racial regime under the mask of crime control.

And if this sounds familiar, it should—because those foundations still shape how modern policing functions.

The presumption that Black presence equals danger.

The belief that control must be immediate and overwhelming.

The legal infrastructure that criminalizes movement, tone, language, noncompliance, and survival.

The disproportionate use of force in “routine” encounters is because the routine is always rooted in domination.

The use of arrest quotas, summons goals, and predictive policing tools to justify patrol saturation in Black and Brown communities mirrors the “sweep and extract” methods of old.

The logic hasn’t changed. Only the language has.

What was once called vagrancy is now called trespassing. What was once loitering is now obstructing pedestrian traffic. What was once plantation enforcement is now “community stabilization.” The system still rewards suspicion, criminalizes presence, and treats the neighborhood, not the act, as the threat.

This is why reform always fails. What needs to be reformed isn’t a policy or a precinct—it’s a purpose. And no one in power wants to acknowledge that the purpose of policing was never to create justice—it was to ensure that justice never interfered with racial order and economic exploitation.

Today, when a Black man is stopped for walking too slowly. When a teenager is slammed to the ground for “resisting.” When a mother is jailed because she couldn’t pay a traffic fine, when a community is blanketed in surveillance drones, license plate readers, and automated suspicion algorithms, we are not witnessing the failure of a sound system—we are seeing the continuation of a very effective one, built to manage those whose freedom was never fully recognized.

Slave patrols didn’t disappear. They were institutionalized, professionalized, and normalized. The names changed, but the mission did not.

That’s why crime persists. Not because we don’t police enough, but because we police instead of confronting the structural violence that policing was invented to protect.

And that is the throughline we must follow into the North—into the factories, the railroads, and the immigrant tenements—where another version of the same control was forged.

That’s where we go next.

IV. Northern Industrial Policing: Strikebreaking, Immigrant Control, and Class Discipline

While the South gave America its blueprint for racialized policing, the North refined a parallel doctrine: class control through industrial enforcement. Contrary to the prevailing myth that police departments were established in the North to protect public order or respond to rising urban crime, the historical record shows a different truth: policing in cities like Boston, Philadelphia, and New York was born from the demands of industrial capitalism to control workers, suppress strikes, and preserve the sanctity of private property.

From the 1830s through the early 1900s, America’s urban centers became the staging grounds for massive labor exploitation. Immigrants—Irish, Italian, Jewish, German, and later Eastern European—were crammed into tenements and conscripted into unsafe, low-wage work in factories, railroads, docks, and mills. These workers endured brutal conditions: child labor, 14-hour days, no health protections, wage theft, and no right to organize.

However, the working class did not remain passive. They organized, struck, and resisted. With each wave of labor rebellion, the political class responded similarly: they sent in the police.

This wasn’t incidental. It was strategic. Municipal police departments were professionalized and funded during growing unrest, not to protect workers, but to control them. Cities like Boston (1838), New York (1845), and Chicago (1855) created centralized police forces whose primary role was to enforce “public order” in ways that consistently favored employers, industrialists, and property owners.

Here’s what that looked like in practice:

Police broke up strikes with clubs and gunfire.

They infiltrated labor meetings and arrested organizers.

They escorted strikebreakers and scabs into factories under armed protection.

They beat, jailed, or blacklisted union leaders.

They refused to intervene when employers deployed private militias, such as the Pinkertons, to attack their workers.

The legal justification was always the same: protection of “peace,” “commerce,” or “critical infrastructure.” But behind the language was a clear directive: defend capital at all costs.

In 1877, during the Great Railroad Strike—the first nationwide strike in U.S. history—state militias and local police killed more than 100 workers and injured countless more in violent confrontations. Not a single employer was held accountable. The message was unmistakable: labor resistance would be treated as lawlessness, and the badge would be wielded as a weapon of economic suppression.

And these weren’t temporary flare-ups. By the late 19th century, urban police forces had become permanent arms of the employer class, outfitted with riot gear, horse-mounted patrols, and jurisdictional authority to criminalize protest under vague statutes like “disturbing the peace,” “obstruction,” or “unlawful assembly.”

Even when workers weren’t striking, they were policed. Immigrant neighborhoods were heavily surveilled, with beat cops walking the same blocks daily, not to build trust, but to enforce curfews, ticket vendors, and “dissuade disorder.” Italian fruit sellers, Irish laborers, Jewish peddlers—all were subject to selective enforcement of petty laws intended to keep them in their place.

The power dynamic was not hidden. It was structured.

In New York City, the police commissioner was a political appointment—a function of Tammany Hall’s machine politics. Officers were expected to toe the line between protecting elites and generating revenue. This is why vice raids were selectively enforced: brothels and gambling halls that paid off the local precinct captain were left alone, while poorer, immigrant-run establishments were raided. Corruption was not a defect of early policing—it was its business model.

This period introduced another critical innovation: the police as a shield against collective accountability. When unsafe working conditions led to industrial disasters, hunger riots erupted over bread prices, and coal strikes halted production in Pennsylvania, the political class didn’t examine the systemic causes—they deployed the police to contain the unrest.

Sound familiar?

This legacy is still with us. When housing activists protest slumlords, teachers strike for livable wages, and fast-food workers organize walkouts, the police are still called not to mediate but to “maintain order.” And “order,” in this context, means protecting commercial interests from the consequences of their exploitation.

Let’s not romanticize the North as more enlightened. The difference between Southern and Northern policing was not moral but economic. The South used the police to preserve slave labor. The North used the police to enforce wage slavery. Both systems depended on the criminalization of resistance, and both relied on the idea that poor people, impoverished immigrants, required supervision, not justice.

By the turn of the 20th century, the link between policing and capital enforcement had hardened into doctrine. Police departments were budgeted, structured, and deployed based on the geography of unrest. “Dangerous” neighborhoods were mapped, monitored, and punished in ways that institutionalized inequality and ensured that enforcement resources flowed not to where harm occurred, but to where power felt threatened.

And to this day, those geographic enforcement maps remain intact. The same neighborhoods that were patrolled for pickpockets and bootleggers in 1890 are patrolled for loiterers and marijuana in 2025. The same communities that were redlined in the 1930s are over-policed today.

These aren’t accidents. They are the residue of policing’s economic design.

So when we hear that policing is about “public safety,” we must ask: whose safety? And from what?

In industrial America, safety never meant protection from poverty, disease, workplace injury, or landlord abuse. Safety meant protecting wealth from those most harmed by its accumulation.

And police were the frontline enforcers of that equation.

This legacy undercuts every modern reform effort. You can retrain officers, upgrade body cameras, and publish transparency dashboards. But as long as the mission of policing is defined by preserving “order” rather than dismantling injustice, we will remain trapped in a cycle of enforcement that punishes poverty and silences dissent.

The next chapter in this story? The formalization of political policing through patronage, machine politics, and organized corruption. That’s where we go next.

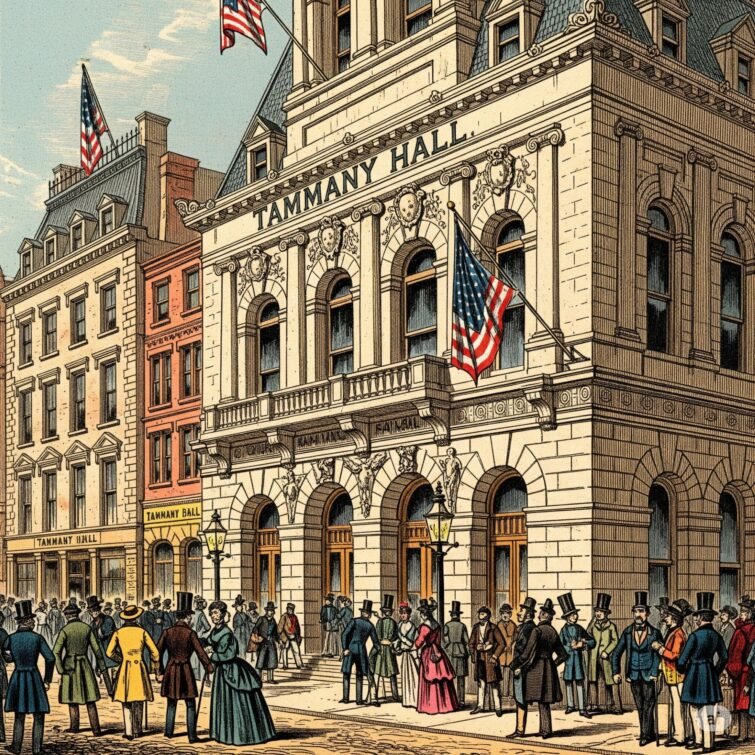

V. Political Patronage: The Tammany Machine and Institutionalized Corruption in the NYPD

By the late 19th century, New York City’s police force was no longer a fledgling institution finding its footing. It had become something else entirely: a central cog in one of American history’s most powerful political machines. And if earlier iterations of policing enforced the racial and economic hierarchies of slavery and labor, the Gilded Age NYPD was the blunt instrument of organized political patronage, serving not law, but the interests of those who controlled City Hall.

At the center of that machine was Tammany Hall—the Democratic Party’s urban power base, notorious for its iron grip on New York politics. What Tammany understood, and what modern observers often forget, is that police power is political power. If you control the beat, you control the street. And if you control the street, you control elections, patronage, graft, and access to the city’s economic bloodstream.

In the Tammany system, becoming a police officer wasn’t about qualifications or public service. It was about connections. A man who wanted to join the NYPD paid a bribe—often several hundred dollars, equivalent to over $10,000 today—to secure an appointment. Promotions were similarly purchased. Assignment to a “good post”—like a busy commercial district where bribes flowed from saloons, gambling houses, or brothels—required political loyalty and cash.

This was not corruption in the abstract. This was organized extortion, and it was institutionally sanctioned.

Beat cops were expected to extract “rent” from local businesses. Captains reported earnings up the chain. Politicians shielded officers from discipline in exchange for loyalty. And if an honest officer refused to play along, he was reassigned, demoted, or quietly pushed out. The department wasn’t broken—it was functioning exactly as designed: a protection racket masquerading as law enforcement.

This structure came to a head in 1894, when a series of scandals forced the creation of the Lexow Committee—a state legislative investigation that exposed the NYPD as a pay-to-play cartel. Witness after witness detailed how officers solicited bribes, falsified arrests, ran side hustles, and participated in the very crimes they were sworn to prevent. Prostitutes paid weekly fees. Illegal casinos made monthly contributions. Barkeeps kept ledgers of who got what. Captains kept lists of debts owed by their precincts to the Tammany bosses above them.

The Committee’s findings were devastating: the department was “rotten to the core,” its leadership indistinguishable from organized crime. And yet, even after the report, very few officers were removed. The machine survived. The model endured. Reform commissions came and went, but the fundamental logic of NYPD power remained: enforce selectively, profit consistently, and protect politically connected interests above all else.

The era also produced another lasting feature of modern policing: selective enforcement as political currency.

In the Tammany years, enforcement was never evenly applied. Prohibition laws, public morality statutes, and vice codes were used not to curb behavior, but to control constituencies. If a district needed to be “cleaned up,” police would raid businesses that didn’t pay. If an opposition candidate gained traction, his supporters’ social clubs might be shuttered. Arrests became tools of retaliation. Police reports became weapons. Surveillance was political, not preventive.

And if any officer dared challenge this structure by whistleblowing, resisting a payoff, or attempting to police “by the book,” they were often exiled to the department’s equivalent of Siberia: distant posts, dead-end shifts, or desk assignments far from their former power base. Retaliation for integrity was baked into the system, a theme that would repeat throughout the 20th and 21st centuries.

Meanwhile, the department’s racial composition remained overwhelmingly white, even as the city’s population diversified. Black New Yorkers, Irish immigrants, Eastern European Jews, and Southern Italians faced vastly different policing experiences—not just because of racism or xenophobia, but because of where they fit within the hierarchy of usefulness to the political machine. The closer a group was to white ethnic power, the more leverage it had to shape or shield its experience with police. The further away it became, the more vulnerable it became to unchecked enforcement.

This wasn’t just corruption—it was governance by coercion, and it cemented several enduring features of modern law enforcement:

The use of police as political enforcers rather than neutral arbiters.

The criminalization of behavior based on utility, not harm.

The normalization of retaliation against officers who challenge the institution’s internal economy.

The extraction of profit from communities under the guise of legal enforcement.

Even today, these dynamics persist. Every time a precinct uses its discretion to ignore one offense but pursue another, every time political influence shields one official while targeting another, and every time a whistleblower officer faces suspension or mental health referral, it echoes the Tammany model. The costumes have changed. The theater has not.

This is why attempts at “depoliticizing” the police are so often doomed. The institution was never apolitical. Its power depends on its entanglement with political machines—whether 19th-century Democratic bosses or 21st-century mayors and police unions.

And this is not confined to New York. The institutional corruption model birthed in the NYPD served as a template replicated in Chicago, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and beyond. The idea that policing should serve capital, suppress dissent, reward loyalty, and punish defiance became national doctrine.

This is why public trust in law enforcement is often lowest in the communities most heavily policed. For generations, those communities have been treated as income streams, not constituencies.

And it’s why even now, the promise of “police reform” rings hollow. You cannot reform an institution whose internal logic was shaped by kickbacks, coercion, and clientelism. You can’t professionalize a machine never designed to serve the public—it was intended to serve those who owned the city.

The next phase in that design? The evolution of policing as a tool not just of local control, but of national order, militarization, and carceral expansion.

We’re going there next.

VI. Jim Crow and Criminalizing Black Existence: Policing as the Engine of Segregation and Carceral Labor

The Civil War ended slavery. It did not end the infrastructure of racial control—it simply forced the state to reengineer it. The result was Jim Crow: an apartheid system enforced not just by law, but by police departments whose job was to translate white supremacy into daily practice. This wasn’t limited to the South. It was national. And it wasn’t informal. It was codified, institutionalized, and enforced with badges, nightsticks, and jail cells.

Policing in the Jim Crow era didn’t merely reflect the values of segregation. It operationalized them.

From the 1870s through the mid-20th century, local and state governments passed hundreds of laws criminalizing virtually every aspect of Black life. These statutes didn’t just restrict civil rights—they created entire categories of race-based crimes, many with no white equivalent: drinking from the wrong fountain, standing too close to a white woman, refusing to leave a train car, asserting a right to vote, failing to call a white man “sir.”

And it was the police who enforced these racial codes, not as a deviation from their duty, but as the centerpiece of their mission.

The modern mythology tells us that the police protect civil society. But in the Jim Crow era, civil society was defined by segregation, and protection meant policing that segregation at every intersection of life—schools, buses, sidewalks, courthouses, diners, neighborhoods, churches, parks, polling places, and prisons.

The officer’s job wasn’t simply to respond to crimes. His job was to preserve the racial boundary, and to do so with impunity.

Black communities understood this intuitively. Encounters with police were rarely about the law. They were about compliance, deference, and humiliation. The risk of arrest—or worse—was omnipresent. Any gesture that could be perceived as “uppity” or “insubordinate” could result in beating, jail, or death. Police didn’t need probable cause—they needed discretion, which was often indistinguishable from racial bias.

This was not a system that tolerated abuse—it required it.

And beyond the physical violence, there was the structural violence of mass criminalization and forced labor. The post–Civil War South gave us the Black Codes and the convict leasing system. Jim Crow perfected it.

By the early 20th century, thousands of Black men, women, and children were being arrested under fabricated or minor charges—vagrancy, gambling, “moral turpitude,” resisting arrest—and funneled into chain gangs and prison farms that generated profit for local governments and private contractors. Entire economies were built on this traffic in Black bodies. And the police were the gatekeepers.

In many Southern counties, the sheriff was the most powerful person, not because he enforced justice, but because he controlled the labor flow to jails, road crews, farms, and corporations. A sheriff who arrested more Black residents brought in more income. A sheriff who enforced “order” too gently risked losing political power.

There was no pretense of neutrality. Crime statistics were tools of extraction, and enforcement was racialized from the moment of contact.

The parallels to today are chilling. When you examine modern systems like stop-and-frisk, broken windows policing, or NYPD summons quotas, the same pattern emerges: low-level offenses used to justify mass enforcement, often divorced from actual harm or threat. The racial disparities in those enforcement patterns are not coincidental. They are echoes—structural remnants of the Jim Crow logic that embedded Black criminality into law enforcement culture.

We can go further: Jim Crow taught modern policing that Blackness itself could be the trigger for enforcement. That lesson remains encoded in contemporary tactics, policies, and attitudes—whether in disproportionate traffic stops, use of force statistics, or prosecutorial charging decisions.

And it’s not just about race. The same tools used to maintain the racial caste system in the South were exported nationally to manage “undesirable” populations—poor whites, Indigenous people, immigrants, and political radicals. Policing became the front end of mass incarceration, and it built its legitimacy on the same racialized, class-based assumptions that underpinned Jim Crow.

The consequences are still with us:

The over-policing of Black neighborhoods.

The use of nuisance laws to drive displacement and gentrification.

The routine use of “disorderly conduct” to justify arrests with no underlying criminal behavior.

The continued denial of bail, due process, and post-arrest protections in communities where courts function more like collection agencies than dispensers of justice.

And what remains most dangerous isn’t just the policies—the ideology. The idea that Black existence, when unregulated, is a public threat. That poverty is criminal. That resistance is aggression. That submission is safe.

That’s the core lie at the heart of the American policing system: its violence is necessary to preserve peace. But in the Jim Crow era, violence wasn’t a response to lawbreaking—it was the law. And policing didn’t counteract that system. It executed it.

The argument that policing can be “reformed” always collapses. History isn’t of a system that lost its way—it’s the history of a system that was perfectly on course, fulfilling the role it was always intended to play: preserving racial and economic caste through legal coercion.

The badge didn’t shield Black people from racial terror. It made that terror official.

And that legacy, like the patrol codes and chain gangs that birthed it, didn’t die with the Civil Rights Act. It evolved into SWAT teams, militarized raids, zero-tolerance mandates, civil forfeiture, mass surveillance, and the statistical sleight of hand that hides disparate impact behind “colorblind” data models.

What began as patrols on horseback became predictive policing software—but the zip codes stayed the same.

And whenever we refuse to confront that legacy, we cover its continuance.

What form did it take next? The War on Drugs—a nationalized, federally funded escalation of the same logic under new branding. That’s where we go next.

VII. War on Drugs and Militarized Enforcement: Policing as Carceral Expansion

By the 1970s, the American public was told a new lie—one wrapped in bipartisan support, media spectacle, and carefully racialized dog whistles: that drugs, not disinvestment, were destroying our communities. That the enemy wasn’t structural poverty, housing segregation, or the collapse of urban labor markets—it was the dealer, the user, the criminal addict.

But the real purpose of the so-called War on Drugs wasn’t to end addiction or dismantle cartels. It was to institutionalize a new national enforcement regime—one that recycled the logic of slavery, the tactics of Jim Crow, and the coercive power of political policing, now wrapped in the language of “public health” and “crime control.”

And at the center of it all were the police, equipped, funded, and unleashed like never before.

In 1971, President Richard Nixon officially declared drug abuse “public enemy number one.” But behind the rhetoric was a far more cynical strategy. As Nixon’s domestic policy advisor would later admit, the War on Drugs was deliberately designed to criminalize Black people and antiwar activists. The tactic was simple: associate marijuana with leftists, heroin with Black communities, and then deploy police power to disrupt, surveil, and arrest.

“We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or Black,” said Nixon aide John Ehrlichman in a 1994 interview. “But by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and Blacks with heroin… we could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings… Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

That confession alone should discredit the entire enforcement regime. But instead, it was turbocharged. The 1980s and 1990s saw an unprecedented escalation in police militarization, fueled by federal funding, political fearmongering, and bipartisan cowardice. The result was a system that rewarded arrest numbers over safety, punished addiction with incarceration, and turned Black and Brown neighborhoods into permanent battle zones.

Under Reagan and Bush, Congress passed sweeping sentencing laws, like the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act, which imposed 100:1 sentencing disparities between crack and powder cocaine, despite being pharmacologically identical. Crack was cheaper, more prevalent in poor Black communities, and heavily policed. Powder was associated with wealthier, whiter users and was barely touched.

The impact was catastrophic and intentional.

Police departments received grants based on drug-related arrests.

SWAT teams—once reserved for hostage crises—became routine tools for serving drug warrants.

No-knock raids escalated, often targeting the wrong homes.

Asset forfeiture laws allowed police to seize property without convictions, creating perverse financial incentives to raid first, justify later.

Community policing was replaced by “Zero Tolerance” mandates, the “broken windows” theory, and CompStat—a data-driven regime that rewarded volume and visibility, not justice.

This was not public safety. It was carceral warfare, fought with police tanks, battering rams, and congressional approval.

And the numbers tell the story:

From 1980 to 2000, the number of people incarcerated for drug offenses increased from 41,000 to over 500,000.

Nearly 80% of those incarcerated for federal drug offenses were Black or Latino.

By 2001, there were more Black men under criminal supervision (incarceration, probation, or parole) than were enslaved in 1850.

These numbers weren’t a failure of policy—they were the intended outcome.

The War on Drugs expanded the footprint of policing far beyond its traditional boundaries. It put cops in schools. It embedded them in public housing. It deputized them as mental health first responders, crisis interventionists, and family court enforcers. It blurred the line between soldier and officer. And all of it was justified under the same banner: crime control.

But what it controlled was mobility, resistance, and access to rights.

Whole generations of Black and Brown youth were marked as criminal before they reached adulthood. Entire neighborhoods became over-surveilled, over-policed, and stripped of due process. Police officers were no longer community members—they were enforcers deployed against the community.

And when the body count rose—from botched raids, from in-custody deaths, from the long trauma of family separation—the system’s architects claimed it was a price worth paying. Or worse, that the very communities being destroyed were to blame.

The War on Drugs didn’t just criminalize substances. It criminalized people. It converted public health into penal control. It swapped treatment for jail, and prevention for pretextual stops.

It also entrenched a surveillance economy that would later metastasize into predictive policing, facial recognition, and algorithmic targeting. Police began collecting data on crimes and people—where they lived, who they talked to, and what corners they stood on. “High crime area” became a justification for everything from stop-and-frisk to warrantless searches.

Once again, the metrics—arrests, citations, “proactive stops”—became the goal, not safety, recovery, or dignity.

That’s how the carceral state grows: not by solving social problems, but by reframing them as criminal ones, then pouring more enforcement into the void created by political abandonment.

The War on Drugs didn’t fail. It succeeded at what it was designed to do: increase the power of police, expand the prison economy, and maintain racial hierarchy through modernized legal means.

It reanimated the logic of slave patrols, Black Codes, and Jim Crow—then dressed it in federal funding and riot gear.

And today, even as politicians claim to be “ending” the War on Drugs, the architecture it built remains intact:

Police departments still use drug enforcement to justify surveillance and raids.

Civil asset forfeiture continues.

Thousands remain incarcerated for nonviolent drug offenses.

Cities still deploy police into crises caused by addiction, trauma, and poverty, then call it justice.

This is not safe. It is policy violence masquerading as order.

And its next evolution came with data policing and the rise of so-called “broken windows” theory, which took the logic of preemptive enforcement and fused it with real-time surveillance, citation quotas, and racialized metrics of “suspicion.”

We’re going there next.

VIII. Broken Windows, Stop-and-Frisk, and “Dots on the Map”: Policing as Statistical Theater

A new mantra gripped American law enforcement by the late 1990s and early 2000s: “data-driven policing.” It promised efficiency, accountability, and precision. But behind the dashboards and PowerPoints was a familiar logic—that the presence of poverty, not harm, signals criminality; that specific neighborhoods, bodies, and behaviors demand constant policing regardless of whether a crime has occurred.

At the heart of this shift was a widely adopted theory that is now embedded in everyday policy: Broken Windows.

First introduced in a 1982 article, Broken Windows claimed that disorder—graffiti, public drinking, loitering, and fare evasion invite more serious crime. According to the theory, if a single window is left broken and unrepaired, it signals that no one cares, and lawlessness will spread. The solution? Enforce every minor violation. Restore “order” through hyper-vigilance. Show presence. Make arrests. Issue summonses. Create deterrence through saturation.

But what this theory ignored—and what police executives embraced—was that its application was never neutral. It was overwhelmingly racialized, class-based, and spatial. Broken Windows became the pretext for zero-tolerance sweeps in Black and Brown communities across New York City. In reality, it didn’t prevent crime—it redefined it.

Under Broken Windows:

Standing outside your building became loitering.

Jumping a turnstile became a potential felony.

Sleeping on a park bench became trespassing.

Selling a cigarette became a death sentence.

These weren’t hypotheticals. They were NYPD policy. By the early 2000s, neighborhoods like the South Bronx, East New York, Brownsville, and Harlem were subjected to daily, algorithmically backed incursions, where the objective was less about stopping violence and more about producing activity.

Because in this new era, policing wasn’t just reactive—it was performative.

With the rise of CompStat—a software platform adopted under Commissioner William Bratton—NYPD precinct commanders were required to show weekly “productivity”: arrests made, stops conducted, tickets issued, and overtime logged. Commanding officers were grilled in closed-door sessions, maps projected on screens, neighborhoods turned into dots on the map, each symbolizing a stop, citation, or detention.

Not a conviction. Not a solved case. Just an event—to show “engagement.”

This is how data became weaponized.

Rather than measuring success by whether people felt safer, policing success became defined by how many people were policed. Officers were pressured to “show numbers.” When some refused, they were transferred, punished, or labeled as underperformers. Others, desperate to comply, stopped innocent people, padded reports, or made low-level arrests with no prosecutorial basis because in the CompStat economy, metrics became currency, and people became targets.

This was the logic behind Stop-and-Frisk—one of the most notorious modern examples of racialized mass enforcement in the country. At its height, the NYPD was stopping over 685,000 people per year, nearly 90% of them Black or Latino, the vast majority of whom had done nothing wrong. Officers stopped men for “furtive movements,” “bulges” that turned out to be wallets, or “matching descriptions” so vague they could apply to entire neighborhoods.

Every stop was entered into the database, and every interaction was used to justify more patrols. Every unjustified stop became a statistical foundation for future overpolicing.

It was enforcement not based on conduct, but on category.

Again, the rationale was prevention. But what was really being prevented? Not crime—but freedom—freedom of movement, freedom to exist without suspicion, freedom from constant surveillance by an armed force trained to see disorder as danger and poverty as pathology.

And again, the outcome wasn’t safety—it was trauma. Whole generations of young people learned early that being stopped, questioned, or thrown against a wall was a rite of passage. That cops could touch you, threaten you, detain you, and lie about why. That “furtive movement” could get you killed.

When litigation came—Floyd v. City of New York—the defense was predictable: officers have discretion. The department isn’t targeting race. The stops are data-driven.

But discretion under pressure is not discretion at all. It’s institutional coercion in tactical clothing.

CompStat didn’t eliminate bias. It legitimized it and cloaked it in charts and KPIs. Broken Windows didn’t stop serious crime. It saturated poor communities with police, generating a flood of minor prosecutions that clogged the courts and devastated lives.

And none of it worked.

A 2014 study found no measurable correlation between Broken Windows enforcement and violent crime reduction. A 2013 federal court ruled that Stop-and-Frisk violated the Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments. And years after CompStat’s peak, the city remains plagued by housing inequality, mental health crises, and economic disinvestment—none of which a citation can fix.

But here’s what these policies did accomplish:

They drove up police budgets.

They justified expanding surveillance infrastructure.

They allowed mayors and police commissioners to claim they were being “tough on crime.”

They created arrest records for hundreds of thousands of Black and Brown residents.

They deflected attention from the deeper failures of social governance by substituting enforcement for investment.

And they normalized a system in which policing performance became more important than its purpose.

That’s the tragedy of modern law enforcement. It’s not that it fails to prevent harm; it was never designed to.

It was designed to:

Occupy neighborhoods are coded as dangerous.

Produce numbers to appease political leadership.

Channel federal and city funding into enforcement infrastructure.

Keep communities in a perpetual state of monitored compliance.

That’s not community protection. That’s a feedback loop of coercion, where police must police more to justify the resources they’ve been given to police.

The next frontiers of this logic are predictive policing, algorithmic bias, and the continued use of enforcement as a substitute for governance.

And that’s where we go next.

IX. Why Policing Can’t Solve Crime: Social Failure, Institutional Misdirection, and the Criminalization of Structural Neglect

Every few years, a new mayor or police commissioner claims they’ve found the formula to “fix crime.” A new strategy. A new task force. A new rebranding of the same tactics. But they never explain why the crime problem keeps returning, no matter how many arrests are made, how many precincts are “saturated,” or how much money gets pumped into enforcement.

They never ask whether policing is even the right tool for the job.

Here’s the truth: policing can’t solve crime because it was never designed to address its root causes. Crime is not simply a breakdown of law—it is a breakdown of social infrastructure. And America has spent the last five decades disinvesting in every institution that might actually reduce it.

Families are destabilized by poverty, eviction, and incarceration.

Schools turned into testing factories and police zones instead of centers of learning and safety.

Healthcare systems that leave trauma untreated and addiction criminalized.

Housing policies that displace rather than protect.

Labor markets that lock out entire generations or trap them in sub-minimum wage employment.

Food deserts, transit inequities, and racialized environmental neglect that pile daily stress on already fractured lives.

These are the engines of crime, not because poverty “causes” criminality, but because chronic deprivation corrodes the relational fabric that prevents harm. When society abandons people, some will turn to survival strategies that the law treats as threats. Instead of addressing that abandonment, the state sends in police to punish the visible symptoms.

It is the policy equivalent of setting fire to a house and blaming the family for escaping through a broken window.

And the statistics confirm this. Violent crime correlates not with a city’s police budget, but with its housing instability, joblessness, childhood trauma exposure, and access to care. The presence of officers may alter reporting patterns or visibility, but it does not address why violence occurs in the first place.

Yet at every policy crossroads, we double down on enforcement. Why?

Policing provides a politically useful illusion of control. It allows elected officials to claim they’re “doing something” without addressing the messy, expensive, long-term work of investing in people. It shifts the narrative from social failure to individual behavior. It converts systemic neglect into a public safety talking point.

It also externalizes blame. When a child brings a weapon to school, we blame their choices, not the school’s funding, the family’s eviction, or the trauma that led them there. When someone is arrested for theft, we ask why they stole, not why basic needs weren’t being met. And when a neighborhood experiences a surge in violence, the call is always for more police, not more mental health clinicians, not more youth programs, not more housing stability.

This isn’t an accident. It’s a design.

Policing, by its very structure, is a reactive, post-harm institution. It arrives after something goes wrong. Its tools are surveillance, detention, and force. It cannot house, educate, feed, or heal you. It can only punish. And yet we’ve asked it to substitute for every institution that no longer functions.

We have built a society where the police are expected to:

Intervene in domestic disputes caused by untreated trauma.

Respond to overdose calls caused by a broken healthcare system.

Evict tenants because housing courts are underfunded, and gentrification is unchecked.

Monitor school children because we’ve replaced counselors with officers.

Manage mentally ill people on the street because inpatient care has been gutted.

And then we act surprised when this fails—when officers, not trained for these roles, escalate, injure, or kill, when people cycle through jail instead of getting help, when families are torn apart for what amounts to state-manufactured crises.

Instead of changing course, we should throw more money at the same institution that couldn’t solve the problem in the first place.

The NYPD’s budget exceeds $11 billion in New York City when all hidden costs are counted, including settlements, overtime, pensions, and outside contract enforcement. That’s more than the city spends on the Departments of Health and Mental Hygiene, Youth and Community Development, and Homeless Services combined.

Imagine what would happen if even a fraction of that money were redirected—not to enforcement, but to prevention:

Safe, affordable housing.

Living-wage employment programs.

Restorative education models.

Community-based violence interruption programs.

Access to trauma-informed therapy and peer support.

We already know these interventions reduce harm. But they’re long-term. They require trust. They shift power away from centralized institutions. This is why they’re rarely prioritized—they can’t be measured in “arrests” or “summonses.” They don’t produce “dots on the map.” They don’t deliver the optics of “action.”

Policing, by contrast, produces results you can see: handcuffs, flashbangs, yellow tape, crime scene vans, press conferences. It looks like something is happening. But what’s happening is containment, not transformation. And that distinction matters—because the more we rely on police to manage the fallout of social collapse, the more we entrench both the collapse and the coercion.

Policing doesn’t fix crime. It manages the symptoms of policy failure.

When it fails—when officers retaliate, abuse power, or violate rights—the institution closes ranks because it must. Its legitimacy depends on the public believing it is both necessary and practical. To admit that policing can’t solve crime is to recognize the entire architecture of public safety is built on sand.

But we need to say it anyway.

Because until we tell the truth—that crime is a social outcome, not a moral defect; that policing is a tactical response, not a strategic solution—we will continue to pour resources into enforcement while starving the systems that could make it obsolete.

Policing is not safety. Investment is. Connection is. Justice is. And we cannot build those through handcuffs.

The final step in this argument? Looking at what happens when policing fails its internal legitimacy test—when political leaders scapegoat officers, when discretion is revoked, when retaliation becomes the institution’s primary language.

That’s where we go next.

X. Retaliation, Scapegoating, and Political Cowardice: How the System Sacrifices Its Own to Protect the Myth

Policing in America isn’t just a failed institution. It’s a self-preserving one. It doesn’t reform—it absorbs critique, redirects blame, and shields the powerful. But the system doesn’t take responsibility when scrutiny becomes unavoidable—when a policy backfires, a lawsuit hits, or a scandal explodes. It doesn’t examine the structure. It finds a scapegoat.

More often than not, it sacrifices one of its own.

It’s a well-worn script: a department mandates zero-tolerance enforcement in a high-profile neighborhood. Officers are given strict instructions—meet your numbers, write the summons, make the stop. There’s no room for discretion. There are quotas in everything but name. The moment one of those encounters becomes newsworthy—when someone is injured, arrested unjustly, or worse—the same political leadership that gave the order steps forward and says:

“The officer acted outside department policy.”

That officer is suspended, reassigned, or placed on modified duty. Press statements are issued. Internal Affairs is mobilized. Politicians demand “accountability.”

But behind the scenes, nothing changes. The command structure, the enforcement plan, and the incentives remain. The officers didn’t go rogue—they followed a playbook written by people who now pretend they’ve never seen it.

And when officers push back—when they try to exercise absolute discretion, raise concerns about unlawful orders, retaliatory practices, or use data to manipulate enforcement—they don’t get support. They get punished.

They’re labeled insubordinate.

Passed over for promotion.

Reassigned to humiliating posts.

Or, in many cases, subjected to psychological review, an increasingly common tactic used to sideline whistleblowers, critics, and internal dissenters. The message is clear: you can either comply with dysfunction or be pathologized.

And for officers of color, women, and LGBTQ+ officers—especially those who speak out—the retaliation is often compounded. They are punished for challenging the institution, and their identities become additional weapons used to discredit them. They’re painted as unstable, disloyal, or “unfit for service”—the same labels once used to justify disparate discipline and selective enforcement.

These are not isolated incidents. They’re patterns.

We’ve seen officers demoted for refusing illegal search orders, others blacklisted for cooperating with federal monitors, and still more subjected to anonymous smears, targeted investigations, or public defamation campaigns. This is not about maintaining integrity. It’s about controlling the narrative and protecting the hierarchy.

If the department admits a policy is flawed, then the brass who designed it are vulnerable. If it admits retaliation is real, then its entire image of internal cohesion collapses. So, instead, it hides behind the illusion of discretion.

“Officers are trained to use their judgment,” they say.

But ask any officer under pressure from CompStat or a no-tolerance initiative how much “judgment” they’re allowed. Ask how their evaluations are affected if their numbers drop. Ask how they’re treated when they prioritize de-escalation over summons production.

The reality is simple: the system incentivizes enforcement, punishes dissent, and weaponizes discretion selectively, only when it’s convenient for the chain of command.

And when the public outcry gets loud, a community rises, or litigation threatens to expose the truth, the same brass who demanded compliance suddenly champion “reform,” usually at the expense of someone lower on the organizational chart.

It’s performative accountability—justice as theater.

Meanwhile, the underlying culture—the secrecy, the retaliation, the political interference—remains untouched.

And political leaders are complicit. City Hall and state legislatures have long used police departments as shields and swords. They rely on law enforcement to carry out austerity-era governance: responding to social crises without funding social institutions. Then, when those crises explode, they blame the officers tasked with managing the fallout.

It’s a cycle of cowardice masked as leadership:

Mandate aggressive enforcement behind closed doors.

Distance yourself when the public reacts.

Offer up a scapegoat.

Promise a new policy that replicates the same logic.

Repeat.

The toll is enormous.

Communities lose trust, officers lose morale, whistleblowers are silenced, lawsuits mount, public money bleeds into settlements, and nothing fundamental changes.

This is why real reform never sticks: The institution has evolved to outsource blame while protecting its architecture. It claims to want change but retaliates against those who suggest it. It trains officers to follow orders, then punishes them when those orders generate harm. It centralizes power, then denies responsibility.

It’s the same strategy used in every top-down coercive system: enforce rigid obedience until obedience becomes a liability, then isolate, expel, or discredit the obedient.

And this isn’t just harmful. It’s dangerous. Because it reinforces the belief—among officers, community members, and policymakers—that accountability is a trap, that truth-telling is a career killer, and that the safest move is silence.

This silence protects the institution. But it kills everything else.

It kills morale.

It kills innovation.

It kills justice.

And in some cases, it kills people—when the wrong order is followed, the wrong home is raided, the wrong suspicion escalates into force.

The system doesn’t just fail to protect the public. It fails to protect the people who carry out its policies. And the more it scapegoats, the more it retaliates, the more transparent the truth becomes:

Policing is not a system of safety. It is a system of compliance.

And when compliance fails to serve the institution’s image, the institution turns inward and devours its own.

This is why real change won’t come from internal investigations or new oversight offices. It must come from rethinking the structure, from challenging the assumption that policing should be the central response to every social problem. That loyalty to a broken system is more important than allegiance to the public.

Because if the institution continues to cannibalize those who speak the truth, eventually, no one will be left to say it.

In the final section, we bring the argument full circle—and ask what it will take to build public safety from the ground up, outside the institution that has claimed it for too long.

XI. Conclusion: Stop Asking the Wrong Institution to Do the Right Thing

You cannot fix what was never designed to heal. And yet for over 400 years, we’ve asked an institution built on extraction, control, and violence to deliver what it was never meant to provide: justice, safety, trust, and peace.

From the Dutch rattle watch to slave patrols, from strikebreaking battalions to Jim Crow enforcers, from the War on Drugs to Broken Windows to CompStat dashboards and predictive policing—American law enforcement has evolved in name, in gear, in mission statements. But its core function has not changed.

Policing has always been the tool of the powerful to manage the people they deem expendable. It was never designed to nurture communities or prevent harm. It was created to enforce hierarchy, secure property, suppress dissent, and preserve order as defined by those with the means to describe it.

Every attempt to reform it—every commission, retraining, policy tweak, or public apology—has one goal: to preserve the institution while pacifying the outrage. Keep the architecture intact. Keep the funding intact. Keep the logic intact.

But you cannot retrain history, you cannot oversee your way out of a foundational purpose, and you cannot install justice into an institution built to disappear it.

This is why the crime problem never disappears. A lack of enforcement doesn’t cause crime—it’s caused by the deliberate starvation of every other institution that creates the conditions for people to live with dignity.

We’ve defunded schools while militarizing precincts.

We’ve closed public hospitals while expanding jail beds.

We’ve shuttered libraries and stocked up on body cameras.

We’ve replaced counselors with cops, caseworkers with court summonses, treatment with handcuffs.

And we’ve convinced ourselves that this is normal—that public safety must always come from a gun, a badge, a blue line, and a billion-dollar budget.

But safety does not come from enforcement. Safety comes from connection, care, trust, and institutions that are resourced, respected, and rooted in the community, not surveillance.

A safe neighborhood is not one with the most officers. It’s one of the few reasons to call them.

That means stable housing, quality education, universal healthcare, meaningful work, restorative schools, green space, accessible food, and collective accountability. These are not “alternatives to policing.” They are what safety looks like.

And until we stop outsourcing harm reduction to a punitive institution, until we stop expecting policing to do what family, education, housing, and health should be doing, we will keep getting the same result:

Communities saturated in force but starved of care.

Officers scapegoated for carrying out orders they didn’t create.

Politicians are hiding behind press conferences and promises.

Billions spent on control and crisis, while the root causes fester untouched.

It’s time to stop asking the wrong institution to do the right thing.

It’s time to start investing—seriously, systematically, unapologetically—in the things that make policing unnecessary in the first place.

Because what we need is not reform.

What we need is a replacement.

Not of individual officers, but of the idea that safety must be imposed from above through force, rather than cultivated from below through care.

That replacement won’t come from inside the system. It will come from outside—through legislation, organizing, resource redistribution, public truth-telling, and sustained pressure from communities that refuse to be policed into submission any longer.

It will come when we reject the myth that policing equals peace.

It will come when we finally say, without apology, that justice has never worn a badge—and never will.