Executive Summary

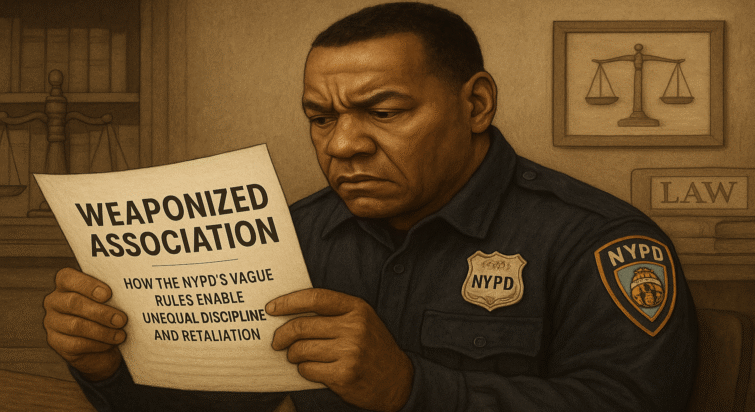

The New York City Police Department (NYPD) operates under a disciplinary regime that purports to uphold integrity, but in practice enables arbitrary punishment, political favoritism, and systemic inequity. At the center of this system is Administrative Guide Procedure No. 304-06(8)(c)—a vaguely worded “criminal association” policy that prohibits officers from “knowingly associating” with individuals “reasonably believed” to be engaged in criminal activity. While framed as a safeguard against corruption, this rule lacks any operational definition, internal guidance, or due process protections. Its ambiguity creates a discretionary tool that is disproportionately deployed against politically disfavored officers, socially marginalized, or merely perceived to fall outside departmental orthodoxy.

This report documents how AG 304-06(8)(c) has evolved into an ideological and identity-based enforcement mechanism. Officers have been investigated or disciplined based on:

A sealed arrest in their family or social network,

Public expressions of dissent or political belief,

Proximity to individuals flagged by metadata, but with no allegation of actual misconduct.

Compounding this ambiguity is the NYPD’s unlawful use of sealed arrest records, in direct violation of New York Criminal Procedure Law §§ 160.50 and 160.55, a 2021 Bronx Supreme Court order, and federal EEOC guidance. These records are used to construct disciplinary narratives even when the arrests are decades old, sealed, or unrelated to any job function. Sealed data becomes a gateway for institutional suspicion and retaliatory discipline.

These problems are enabled by the unchecked disciplinary authority of the Police Commissioner under Administrative Code § 14-115 and the investigatory subpoena powers granted under § 14-137. Together, they create a self-reinforcing system of internal retaliation:

Disciplinary outcomes are routinely overridden without explanation.

Subpoenas are issued without judicial review or an evidentiary basis.

Psychological referrals and Risk Management flags are used to marginalize officers, especially whistleblowers, women, and officers of color.

The report also outlines this system’s chilling effect on the department’s rank and file. Officers disengage, censor their social lives, avoid reporting misconduct, and withdraw from community work—not because they are unfit, but because they fear reprisal for deviating from internal expectations. Over time, the disciplinary system becomes not a guardian of ethics, but a vehicle for institutional control that undermines constitutional rights and corrodes internal trust.

Key Legal and Structural Findings:

Vagueness in policy violates the Due Process Clause (Loudermill, Papachristou).

The use of sealed records contravenes CPL §§ 160.50, 160.55, and federal civil rights law (EEOC 2012 Guidance).

Discretionary discipline without independent review breaches fairness and invites viewpoint discrimination (Pickering, Rankin, Vitarelli).

Unequal application of rules creates disparate impact under Title VII, NYSHRL, and NYCHRL.

Reform Recommendations:

Codify AG 304-06(8)(c) with specific definitions, training, and written standards for enforcement.

Ban internal use of sealed records, with criminal penalties for violations and independent oversight.

Amend NYC Admin. Code §§ 14-115 and 14-137 to require hearings, written cause, and independent review.

Protect whistleblowers from retaliatory psychological or performance referrals.

Amend Admin. Code § 14-186 to require public reporting on:

Disciplinary overrides,

Sealed record usage,

Risk Management referrals.

Create a civil rights settlement disclosure registry to identify patterns of discrimination and retaliation.

Establish an external oversight board with full authority to review internal NYPD disciplinary decisions.

Conclusion:

The NYPD’s current disciplinary architecture does not merely tolerate bias and retaliation—it institutionalizes them. A system that disciplines based on perception, association, or belief, rather than conduct, cannot credibly claim to protect public safety or constitutional rights. Structural reform is no longer an option. It is a civil rights necessity.

I. Introduction: When Internal Policy Becomes Political Weaponry

The disciplinary machinery of the New York City Police Department does not simply punish misconduct—it determines who holds power, who remains silent, and who is discarded. At the center of this machinery lies a deceptively simple policy: a prohibition against “criminal association,” now codified as Administrative Guide Procedure No. 304-06(8)(c). It forbids officers from knowingly associating with individuals “reasonably believed” to be engaged in criminal activity. On paper, this sounds prudent. In practice, it is a tool of unaccountable power—intentionally vague, selectively enforced, and weaponized to silence, sideline, and expel officers deemed inconvenient to the department’s internal politics.

Unlike legitimate disciplinary standards rooted in clearly defined misconduct, the “association” rule is a blank check. There is no formal definition of “association,” no procedural guidance on “reasonable belief,” and no due process framework to govern how these allegations are investigated or adjudicated. This vacuum is not accidental. It provides a pliable pretext that can be stretched or ignored entirely, depending on who the officer is, what they represent, and whom they’re perceived to align with.

This blog explores how the NYPD’s disciplinary regime exploits the ambiguity of its own rules to enforce arbitrary and unequal discipline, particularly against officers who lack political capital or institutional protection. What begins as a policy to protect integrity becomes a mechanism to preserve hierarchy. Vague rules become vehicles for ideological policing, sealed records become weapons for guilt by association, and Commissioner-level authority, insulated from oversight under New York City Administrative Codes §§ 14-115 and 14-137, becomes the final hammer to silence dissent.

But this is not just about the internal process. The NYPD’s disciplinary system reflects a broader social dynamic familiar across American institutions: those with access, influence, or “hooks” are shielded; those who are Black, Hispanic, female, or otherwise marginalized face harsher discipline, fewer options, and longer exile. It is a microcosm of structural inequality disguised as professional standards.

The following sections expose how this system functions, not as a neutral arbiter of conduct but as a tool of constructive unfair discipline and retaliation. We analyze the legal failings, cultural consequences, and urgent structural reform needs. This isn’t merely a matter of internal policy—it’s a civil rights crisis wearing the badge of discipline.

II. Policy Without Principle: The Vagueness of AG 304-06(8)(c)

The NYPD’s Administrative Guide Procedure No. 304-06(8)(c) prohibits officers from “knowingly associating with persons reasonably believed to be engaged in, likely to engage in, or to have engaged in criminal activity.” But this language is both expansive and undefined. The terms “associate,” “reasonably believe,” and “criminal activity” are left deliberately vague. There is no training that clarifies the scope of the policy, no published criteria to define prohibited conduct, and no procedural guidance to ensure consistent enforcement. What appears on paper to be an ethics safeguard is, in practice, a blank check for arbitrary discipline.

Such vagueness is not merely a matter of poor drafting—it raises serious constitutional concerns under federal and New York State law. The Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment requires that policies governing public employment provide sufficient clarity to ensure fair notice and guard against arbitrary enforcement. While courts apply the vagueness doctrine most stringently to criminal statutes (Connally v. General Construction Co., 269 U.S. 385 (1926)), the same principles apply—albeit with a lower threshold—in administrative and disciplinary contexts.

In Cleveland Board of Education v. Loudermill, 470 U.S. 532 (1985), the Court held that public employees with a property interest in their job are entitled to basic procedural protections before discipline is imposed, including notice of the charges, an explanation of the evidence, and an opportunity to respond. But under AG 304-06(8)(c), officers are subjected to internal investigations, placed on modified duty, referred for psychological evaluation, or even suspended—often without knowing what specific conduct triggered the investigation or being given the chance to contest the alleged “association.” This lack of procedural integrity renders the rule incompatible with the fundamental fairness required by Loudermill.

If the NYPD were sincere about ensuring integrity through this policy, it would have defined its operative terms long ago. Employees would receive formal training on what constitutes an “association,” internal guidance on assessing “reasonable belief,” and documented standards to ensure fair application. But none of these safeguards exist. Employees are punished for violating rules they were never given the tools to understand, while the department reserves full discretion to reinterpret the rule’s meaning depending on the target. This internal legal contradiction does more than undermine fairness—it exposes a regime of control dressed as discipline. The department cannot credibly claim to uphold integrity while enforcing a rule that no one can objectively define.

Worse, the policy does not operate in a vacuum. Its vagueness interacts directly with power and privilege, producing radically different outcomes depending on where an employee sits in the department’s hierarchy. A junior officer with a cousin who has a sealed arrest may be subject to Internal Affairs scrutiny. A female officer rumored to have once dated someone with a criminal history might find herself flagged by Risk Management or referred to Health Services. Meanwhile, a Deputy Inspector photographed with a known organized crime figure at a charity event may never receive so much as a phone call. The more institutional favor, rank, or political sponsorship an employee enjoys, the less likely “association” becomes a liability. For those without protection, particularly Black, Hispanic, female, and socially marginalized White officers, this rule becomes a trapdoor.

This dynamic is precisely what the United States Supreme Court warned against in Papachristou v. City of Jacksonville, 405 U.S. 156 (1972), where it struck down a vagrancy ordinance that gave police too much discretion to punish conduct selectively. It is also echoed in Vitarelli v. Seaton, 359 U.S. 535 (1959), which held that public agencies must adhere to established disciplinary standards and cannot enforce rules arbitrarily—even in paramilitary environments like the armed forces, Parker v. Levy, 417 U.S. 733 (1974), recognized that vagueness can enable viewpoint discrimination and suppress dissent. Within the NYPD, AG 304-06(8)(c) functions in precisely this fashion: selectively, subjectively, and shielded from meaningful review.

Ultimately, this policy is not about enforcing a standard of conduct but preserving an internal hierarchy. “Association” becomes a proxy for institutional power. It enables not integrity but inequality. It is used not to protect the department from corruption, but to protect the leadership from dissent. And because it lacks clarity, structure, and procedural safeguards, it does not meet constitutional muster. It meets political needs.

III. Selective Enforcement: Institutional Power as a Shield

The power of a vague rule lies not only in how it is written but in who gets to decide when—and against whom—it will be enforced. In the NYPD, AG 304-06(8)(c) is enforced with one hand and ignored with the other. It operates less as a universal standard than as a disciplinary filter, applied rigorously to the powerless and sparingly, if at all, to those in positions of institutional privilege.

Line officers, probationary employees, whistleblowers, and individuals already scrutinized for other reasons often find themselves investigated under the guise of “association” based on the thinnest connections. A family member’s sealed arrest. A rumor of past romantic involvement with someone implicated in a crime. A photograph from a public event with a large, diverse crowd. Any of these may trigger a formal investigation—or worse, internal referral to Health Services or Risk Management—as if proximity itself were proof of disloyalty or corruption.

Contrast this with how the department treats high-ranking officials. For instance, former NYPD Commissioner Edward Caban frequented Con Sofrito, a Bronx lounge operated by his brother and long rumored to attract individuals with organized crime ties. Hundreds of NYPD officers and executives visited the establishment. Yet despite this publicly known association, the location was never designated a “corruption-prone location.” No internal alerts were issued, inquiries were launched, or action was taken.

The same applies to other top brass photographed alongside political powerbrokers, controversial donors, or individuals with long criminal histories. So long as they remain within the department’s protected orbit, the “association” rule does not apply. And even when it does, Internal Affairs quietly resolves, dismisses, or preemptively sanitizes the Situation.

This discrepancy is not anecdotal—it is systemic. The NYPD’s Independent Panel on Disciplinary Reform explicitly acknowledged in its 2019 report that the disciplinary system disproportionately benefits those with political connections, social capital, or internal “hooks.” The report found that decisions about discipline are often shaped by personal influence, favoritism, and non-transparent relationships between senior officials and those under investigation. This is not integrity enforcement—it is internal patronage management.

Such selective enforcement also undermines public and internal trust. It sends a clear message to officers: rules are not rules—they are tools. They can be used against you if you fall out of favor or raise your voice. But they will be ignored if you are protected. In this environment, discipline ceases to be about conduct and becomes about compliance—compliance with the hierarchy, with unspoken political expectations, and with the informal norms that define institutional survival.

From a civil rights perspective, this double standard reinforces patterns of racial, gender, and class disparity within the NYPD. Employees of color, particularly Black and Hispanic members, as well as women and whistleblowers from any background, are disproportionately targeted under policies like AG 304-06(8)(c). Their relationships are scrutinized more closely. Their proximity to criminalized communities is treated with suspicion. Their access to institutional defenders is limited. In effect, the same “association” that is invisible for a white executive from Long Island becomes grounds for discipline when applied to a Hispanic officer from the South Bronx.

This unequal application is not just unethical—it is unconstitutional. It undermines principles of equal protection, exposes the department to Title VII disparate impact claims, and reflects a pattern of institutional retaliation disguised as rule enforcement. When discipline is enforced according to one’s institutional standing rather than the facts of one’s conduct, the rule becomes suspect, and its enforcement becomes illegitimate.

Ultimately, AG 304-06(8)(c) functions not as a guardrail against corruption, but as a mechanism of selective vulnerability. It enables the department to project an image of internal control while preserving immunity for those closest to power. It enforces silence, punishes dissent, and erodes any meaningful distinction between ethics and expediency.

IV. Administrative Overreach: §§ 14-115 and 14-137 as Tools of Arbitrary Discipline and Retaliation

If AG 304-06(8)(c) ‘s vagueness justifies, New York City Administrative Code §§ 14-115 and 14-137 provide the machinery. These two provisions grant the Police Commissioner unchecked authority to impose discipline and subpoena information, respectively, with no required hearings, independent oversight, or enforceable standards. In effect, they convert ambiguous allegations into disciplinary consequences through a closed loop of power that is unanswerable to anyone outside the department.

A. Absolute Discretion Under § 14-115

New York City Administrative Code § 14-115 empowers the Police Commissioner to discipline, suspend, or transfer any member of the NYPD at their discretion. The statute does not require:

A neutral fact-finding process,

Written justifications for deviations from internal recommendations,

Or any mechanism for independent review.

This is not a hypothetical concern. The NYPD’s 2019 Independent Panel Report found that:

The Commissioner regularly overrides the Deputy Commissioner of Trials’s recommendations, especially in high-profile or politically sensitive cases.

These overrides are often made without documented rationale and sometimes after informal intervention by the accused’s political or personal allies.

There is no public accounting, centralized tracking, or consistency in outcomes.

This unaccountable discretion allows political favoritism to thrive. Officers with institutional protection—through union clout, family legacy, or executive patronage—are diverted into lighter penalties, counseling, or non-disciplinary referrals. Meanwhile, disfavored officers, particularly those who report misconduct, challenge leadership, or come from marginalized communities, are disciplined harshly and without explanation.

This kind of selective application of authority violates core due process protections. As the Supreme Court held in Vitarelli, disciplinary actions must follow established standards even when employment is at-will or discretionary. Arbitrary variance—especially when shaped by bias—erodes the legitimacy of any system that claims to be based on merit or fairness.

B. Investigatory Overreach Under § 14-137

Compounding this imbalance is the Police Commissioner’s power under New York City Administrative Code § 14-137, which authorizes the NYPD to issue administrative subpoenas in internal investigations. There is:

No requirement of judicial approval,

No probable cause threshold,

And there is no mechanism to challenge overly broad or retaliatory subpoenas.

In theory, § 14-137 enables internal oversight. In practice, it is a tool of internal surveillance and ideological policing. Officers have been subpoenaed for:

Their private communications,

Metadata about their associations and political activity,

And background materials to support “association”-based investigations with no underlying misconduct.

The result is an investigatory dragnet, often aimed not at uncovering wrongdoing, but at punishing dissenters or manufacturing disciplinary grounds after the fact. This raises significant constitutional concerns. The Supreme Court in See v. City of Seattle, 387 U.S. 541 (1967), and Donovan v. Lone Steer, Inc., 464 U.S. 408 (1984), held that administrative subpoenas must be limited in scope and relevant to a legitimate inquiry, or else they constitute an unlawful search under the Fourth Amendment.

C. A Disciplinary Apparatus Built for Retaliation

Together, §§ 14-115 and 14-137 form a disciplinary regime with no guardrails. One hand authorizes punishment without hearing or explanation; the other enables information-gathering without cause or constraint. This structure:

Invites retaliation against whistleblowers and internal critics,

Rewards institutional loyalty over professional integrity,

It produces vastly unequal outcomes based on race, rank, and political favor.

As the Independent Panel Report documented, the disciplinary system works best for those with “hooks”—personal, familial, or political connections to power. It works worst for the very employees most in need of procedural protection: Black and Hispanic officers, women, probationary employees, disenfranchised employees, and those who challenge the status quo. In that way, the NYPD’s disciplinary regime is not just flawed but a microcosm of structural inequality throughout society, broadly.

These internal mechanisms do not merely tolerate discrimination and retaliation—they institutionalize them. When a vague rule like AG 304-06(8)(c) is enforced through the unchecked discretion of § 14-115 and the invasive powers of § 14-137, the result is not ethics enforcement—it is hierarchical discipline by design. The message is clear: loyalty is protected, dissent is punished, and the rules bend with the power of the person being judged.

The combined effect of § 14-115’s unchecked disciplinary discretion and § 14-137’s investigative latitude creates a disciplinary architecture that tolerates abuse and systematizes it. Officers who report misconduct, challenge institutional narratives, or belong to socially marginalized groups face an opaque, retaliatory process with no meaningful recourse. This is not simply a policy failure. It is a constitutional injury that violates principles of due process, equal protection, and freedom from retaliatory state action. In any other context, such a regime would be called what it is: a retaliatory apparatus cloaked in the language of discipline.

V. Sealed Records as Weapons: Constructing Misconduct from Stigma

If vague rules and unchecked authority form the skeleton of the NYPD’s retaliatory disciplinary regime, the misuse of sealed arrest records supplies the flesh. These records—legally off-limits under state law—are repeatedly accessed, interpreted, and leveraged to construct allegations of “criminal association” against disfavored officers. The practice is not only unlawful. It is structurally embedded in the department’s internal machinery, reinforcing bias, entrenching stigma, and supplying a steady stream of pretext for punishment.

A. Illegal Access and Misuse of Sealed Records

Under New York Criminal Procedure Law §§ 160.50 and 160.55, sealed arrest records are confidential. They cannot be disclosed or used for employment without narrowly defined exceptions. In 2021, a Bronx Supreme Court order reaffirmed that NYPD personnel are barred from using sealed information in investigations, disciplinary actions, or evaluations. Yet despite these legal restrictions—and the constitutional protections of informational privacy—the practice continues.

Officers targeted for disciplinary action or flagged by Risk Management have been subjected to internal inquiries rooted in sealed arrests involving family members, ex-partners, neighbors, or former acquaintances. These inquiries often lack any nexus to job performance or misconduct. However, a sealed record becomes an entry point for fishing expeditions and character judgments in the hands of internal affairs or other internal investigators. The mere fact of proximity to a sealed arrest becomes “reasonable belief” under AG 304-06(8)(c)—turning stigma into suspicion and suspicion into process.

B. The EEOC, DOJ, and the Civil Rights Framework

The NYPD’s use of sealed records flies in the face of federal civil rights guidance. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) has long warned against using arrest records, especially non-convictions, in employment decisions. The agency’s 2012 Enforcement Guidance emphasizes that:

Arrests alone are not evidence of criminal conduct, and

Employers must demonstrate that any consideration of criminal history is job-related and consistent with business necessity.

Similarly, in April 2016, the U.S. Department of Justice revised its internal policies to eliminate stigmatizing language like “felon” or “offender,” adopting person-first language that affirms the dignity and reintegration of justice-involved individuals. These shifts reflect a broader legal and sociological recognition: criminal record stigma is real, it is racially coded, and its unchecked use perpetuates structural inequality.

Yet within the NYPD, sealed records remain an informal currency of suspicion—used not to promote safety or integrity, but to construct narratives of unfitness when institutional loyalty is in doubt. The result is a system in which marginalized officers are perpetually vulnerable to discipline not because of what they have done, but because of what data can be distorted to suggest.

C. From Guilt by Conduct to Guilt by Algorithm

The misuse of sealed records intersects with the NYPD’s broader risk scoring and metadata surveillance apparatus. Internal tools like the Risk Management System and Psychological Review pathways often rely on opaque algorithms, subjective referrals, and data triggers—including past investigations or known associations—to flag officers for further review. In many cases, sealed arrests—though legally inadmissible—are quietly folded into these assessments through internal access or off-the-books disclosures.

This integration allows the department to produce disciplinary momentum from mere data shadows. When a command wants an officer removed, neutralized, or discredited, a sealed record in the orbit of that officer becomes a powerful accelerant. Under AG 304-06(8)(c), it is enough to establish “reasonable belief.” Under § 14-137, it becomes the basis for sweeping subpoenas. Under § 14-115, it becomes the pretext for suspension or reassignment. The officer is not allowed to challenge the record, explain its irrelevance, or seek redress—because, formally, the sealed record “doesn’t exist.”

This is Kafka by way of CompStat.

D. Criminal Record Stigma and Civil Rights Harm

The criminalization of identity in the United States is not a marginal phenomenon—it is structural and far-reaching. According to the Center for American Progress, as many as 100 million Americans—one in three adults—have some form of criminal record. A person in the U.S. is more likely to have been arrested by age 23 than to hold a college degree. Yet even a minor record, such as a misdemeanor or a mere arrest without conviction, can impose lifelong barriers to employment, housing, education, and credit. This is not incidental—it is by design. The system has turned data contact into a proxy for moral failing, erecting invisible walls around millions of people, especially those already on the margins.

The consequences are profound and uneven. Black men are six times more likely to be incarcerated than white men; Hispanic men, 2.5 times more likely. More than 60% of formerly incarcerated individuals are unemployed one year after release, and those who do find work earn 40% less than their peers. With 87% of employers conducting background checks, the message is clear: presence in a database, regardless of outcome, is enough to mark someone unemployable. The economic fallout is staggering: In 2008 alone, excluding justice-involved individuals, the U.S. economy suffered an estimated $65 billion in lost GDP. However, the deeper harm is social and democratic. When sealed arrests are secretly used to justify punishment, when vague rules transform association into guilt, and when internal police discipline mirrors the very disparities of mass incarceration, the system reveals itself, not as broken, but as faithfully executing its intended function.

The NYPD not only reflects this phenomenon, but it also institutionalizes it. Officers are not evaluated based on conduct, but on the criminal record status of those around them. In this logic, proximity becomes complicity, and data becomes guilt. This logic reproduces racial and class bias. Officers from communities heavily policed by the department are far more likely to have family or community ties to people with sealed records. Thus, AG 304-06(8)(c), when enforced through sealed record access, becomes a proxy for racial exclusion—a covert method of disciplining identity under the guise of policy.

E. Constitutional Violations and the Disappearance of Due Process

The NYPD’s continued use of sealed records in disciplinary investigations violates:

State law (CPL §§ 160.50, 160.55),

A court order, and

Federal civil rights guidance.

But more broadly, it violates the constitutional guarantee of due process. Officers are not notified that sealed records are being used against them. They are not allowed to contest the records, explain the context, or confront the alleged basis of discipline. Instead, they are subjected to an opaque, stigmatizing, and retaliatory process by design.

This isn’t about conduct—it’s about control. Tainted or unauthorized data would be grounds for dismissal in any ethics enforcement system. In the NYPD, it becomes the foundation of career-ending action. That inversion of logic tells us everything we need to know about how the disciplinary system functions—not to uphold fairness, but to reinforce hierarchy.

VI. From Policy to Pattern: The Civil Rights Crisis Behind Criminal Record Stigma

In a country that brands itself as a beacon of liberty, the widespread use of arrest and criminal history data to justify exclusion, particularly against people who were never convicted of a crime, exposes a more profound truth: freedom in the United States is contingent, racialized, and data-driven. Across the public and private sectors, the mere fact of arrest—sealed, dismissed, or decades old—is enough to disqualify an individual from employment, housing, education, credit, and public trust. This is not a side effect of overpolicing—it is a central feature of American governance, and its logic has been internalized at every level, including within the ranks of law enforcement itself.

As Section V laid bare, the NYPD enforces this logic internally by misusing sealed records to justify disciplinary actions under AG 304-06(8)(c). Officers are not judged by conduct, but by social, familial, geographic, or algorithmic data associations. That pattern is not unique to the department. It is part of a national crisis in which contact with the criminal legal system becomes a permanent mark of suspicion, however minor or irrelevant.

According to the Center for American Progress, nearly 1 in 3 adults in the U.S. has a criminal record, and more Americans are arrested by age 23 than graduate from college. The disparities are stark: Black men are six times more likely to be incarcerated than white men, and Latino men are 2.5 times more likely. The cumulative impact is devastating. More than 60% of formerly incarcerated people are unemployed a year after release, and those who find work earn 40% less than their counterparts. With 87% of employers conducting background checks, these statistics are not just a reflection of bias—they are the product of policy embedded in every institutional layer, from job applications to internal NYPD discipline.

Sociologists describe this as labeling theory—the idea that people, particularly from marginalized communities, are marked not by what they do but by how society categorizes them. In the United States, the dominant label is “criminal.” It is a racialized, class-based identifier that strips away individuality and context. Once applied, it becomes self-reinforcing: blocking access to opportunity, amplifying stigma, and accelerating surveillance. The criminal record justifies anything, from firing a whistleblower to denying housing or custody.

The DOJ’s 2016 policy shift away from dehumanizing terms like “felon” and “offender” was an acknowledgment of this harm. The EEOC’s guidance also limited the use of arrest records in employment decisions. But these efforts are undermined when law enforcement agencies themselves continue to rely on sealed or extrajudicial data to discipline and retaliate against their personnel, especially when that discipline is concentrated on officers of color, women, or those without internal protection.

In this way, the NYPD’s misuse of sealed records does more than violate CPL §§ 160.50 and 160.55 or a 2021 Bronx Supreme Court order. It reinforces a national system of second-tier citizenship, in which a criminal record—or even proximity to one—is enough to justify exclusion. It mirrors and magnifies the broader structural inequalities of American life: racialized policing, discriminatory algorithms, employer blacklists, and institutional gaslighting dressed up as accountability.

What the NYPD is doing is not exceptional—it is emblematic. It reflects how arrest record stigma functions not just as a collateral consequence but as an intentional mechanism of social control. And when the law enforcers begin to deploy that mechanism internally—turning sealed records into disciplinary ammunition—the system reveals itself not as broken but as operating precisely as designed.

VII. Guilt by Belief: Ideological Enforcement Disguised as Discipline

Once criminal record stigma is accepted as a legitimate basis for exclusion, it becomes dangerously easy to extend that logic beyond proximity to alleged misconduct—and toward the policing of thought, belief, and affiliation. This is where the NYPD’s “criminal association” rule morphs from a tool of data-driven exclusion into an instrument of ideological retaliation. Officers are not just disciplined based on who they know, but increasingly because of what they believe, say, or refuse to perform in silence.

Under AG 304-06(8)(c), an officer need not commit misconduct—or even associate with someone who has—to become a target. A rumor of support for a political cause. A social media “like.” Attendance at a protest. A family member’s record. A perceived refusal to “toe the line.” These forms of association become pretexts for surveillance, performance review flags, subpoena activity under § 14-137, or outright suspension under § 14-115. And because no internal guidance or legal threshold defines “association,” belief becomes behavior, and perception becomes policy.

This shift is not incidental—it is strategic. It allows the department to enforce internal orthodoxy under the guise of integrity. Officers who voice criticism, support controversial reform, or express views outside the dominant cultural narrative often face scrutiny. Yet those who enjoy political protection—whether through race, rank, personal connections, or ideological alignment—are rarely subjected to the same rules. The disciplinary system’s subjectivity becomes its weapon, punishing deviation rather than misconduct.

This environment produces a chilling effect. Officers stop reporting misconduct. They disengage from their communities. They censor their social lives. They learn that professional survival requires ideological conformity, not just legal compliance. This is particularly acute for Black, Hispanic, female, and LGBTQ officers—individuals whose presence in law enforcement is already viewed through a lens of institutional suspicion. For these officers, any deviation from the cultural norm—whether in attire, association, speech, or stance—is not only visible, it is punishable.

The consequences are not merely professional. They are constitutional. The First Amendment protects freedom of association, political belief, and expression—even within public employment. The Supreme Court has long recognized that public employees do not shed their rights at the workplace door. In Pickering v. Board of Education (1968) and Rankin v. McPherson (1987), the Court held that speech on matters of public concern—especially concerning government operations—is protected unless it materially disrupts agency function. The NYPD’s use of “association” policies to punish ideological disfavor fails that test entirely.

Moreover, when belief is used as a proxy for misconduct, and sealed records or informal social data are deployed to construct justification, the result is not merely retaliation but viewpoint discrimination. It transforms internal policy into state-sponsored suppression, where discipline becomes a political tool. And where that suppression targets those from historically marginalized groups, it implicates not only the First Amendment, but equal protection under the Fourteenth.

The department’s treatment of officers perceived as politically nonconforming is not an overreach—it reflects a more profound logic: discipline is not about ethics—it’s about control. Whether by weaponizing sealed records, enforcing association rules without standards, or targeting dissent through bureaucratic proxies, the NYPD’s internal disciplinary regime operates as a mechanism of ideological policing by proxy, hidden behind the language of professionalism.

In the next section, we turn to the consequences of this regime, not just for those punished but also for those watching. When silence becomes the only way to survive, the system doesn’t just punish dissent—it destroys integrity from within.

VIII. The Chilling Effect: Retaliation by Policy Design

Silence becomes a survival strategy in an organization where discipline can be triggered by mere belief, proximity, or perception. Over time, that silence calcifies into institutional culture. Officers learn quickly that speaking up, standing out, or affiliating with the “wrong” people—even passively—can jeopardize their careers, reputations, or psychological well-being. This is not incidental fallout. It is the intended consequence of a disciplinary system that substitutes ambiguity for fairness and hierarchy for accountability.

The chilling effect is not just theoretical—it is behavioral. Officers stop reporting misconduct because they know the target will shift to them. They avoid community ties that could appear suspicious in the department’s metadata-driven surveillance matrix. They disengage from workplace conversations, avoid mentoring at-risk youth, and opt out of civic life. Some even refuse to seek peer or therapeutic support out of fear that vulnerability will be interpreted as liability. This is not discipline—it is institutional self-harm.

The effects are especially acute for officers from historically marginalized groups. Black, Hispanic, female, LGBTQ+, and immigrant officers are routinely treated as suspects from the outset, regardless of their conduct. For them, compliance is not enough. They must constantly prove institutional loyalty—over and above their white, male, or politically protected counterparts—while navigating a system rigged to read any deviation from cultural conformity as a threat. A hairstyle, a flag, a friendship, a tweet—any of these can be weaponized.

The damage is also relational. The chilling effect corrodes trust between officers and the public and within the department. Whistleblowers become pariahs. Ethical supervisors are marginalized. Investigators learn that truth-seeking can be professionally dangerous. In time, the department’s internal integrity mechanisms—its Equity and Inclusion offices, Risk Management units, and psychological services—become less trusted, less utilized, and more performative. They exist on paper but not in practice. Like the “association” rule, they are tools of appearance, not substance.

This cultural decay is compounded by legal uncertainty. Because the rules are vague and discipline is discretionary, officers have no stable framework for understanding what is punishable. The absence of clear boundaries creates an environment where fear replaces fairness and discretion becomes indistinguishable from discrimination. This is the very antithesis of a lawful organization. It is governance by rumor, policy by proxy, and retaliation by design.

At its core, the chilling effect destroys institutional ethics from within. When officers must choose between integrity and survival, and when the cost of speaking truth is exile, demotion, or psychological referral, silence becomes not just common—it becomes rational. But in this rational silence, the institution loses its capacity to self-correct. Misconduct becomes normalized. Harassment becomes embedded. Retaliation becomes structural.

This is how cultures collapse—not with public scandal but with private capitulation. The NYPD, like any institution governed by fear and favor, risks becoming not an agent of public safety but a mirror of the dysfunction it was sworn to resist.

IX. Rebuilding from Within: Structural Reform to Restore Integrity and Rights

The NYPD’s disciplinary machinery, as currently constructed, is incapable of delivering justice or accountability. It does not merely fail to deter misconduct—it perpetuates it, particularly when the accused are politically protected and the complainants are structurally marginalized. Fixing this system requires far more than retraining or rewording policies. It requires dismantling the core architecture of arbitrary authority, data misuse, and ideological policing, and replacing it with a framework rooted in transparency, fairness, and constitutional fidelity.

A. Codify and Constrain “Association” Policy

The criminal association rule in AG 304-06(8)(c) must be formally codified, narrowly tailored, and legally bounded:

Define “association” with objective, specific criteria rooted in actual misconduct, not mere proximity or perception.

Prohibit the use of sealed arrests or non-conviction data in evaluating “reasonable belief” under the rule.

Documented justification is required for any discipline initiated under this policy, subject to audit and review.

Without these safeguards, the rule is a blank check for political retaliation and racialized control masquerading as ethics enforcement.

B. End the Internal Use of Sealed Records

The NYPD’s continued access to and internal use of sealed arrest records flagrantly violates:

CPL §§ 160.50 and 160.55,

A 2021 Bronx Supreme Court order, and

Federal guidance from the EEOC and DOJ.

The City Council and State Legislature must enact legislation to:

Create criminal penalties and civil liability for agencies that misuse sealed data.

Establish an independent compliance monitor with full access to NYPD risk systems and investigative files.

Mandate annual reporting on all uses of sealed or expunged records within city agencies.

No justice system can claim legitimacy while secretly weaponizing data that is supposed to be erased.

C. Reform §§ 14-115 and 14-137: End Unreviewable Discretion

The Police Commissioner’s unilateral powers under Admin. Codes §§ 14-115 and 14-137 must be brought into constitutional compliance:

Require pre-deprivation hearings for all suspensions, transfers, and adverse employment actions.

Prohibit administrative subpoenas unless supported by a written finding of job-related cause and subject to independent review.

Create an external discipline oversight board, empowered to investigate and publish reports on the discretionary use of these statutes.

As currently written, these statutes are incompatible with the due process guarantees of the Fourteenth Amendment and the protections against viewpoint discrimination under the First.

D. Protect Whistleblowers and Internal Dissent

Retaliation cloaked as discipline undermines individual rights and the department’s operational integrity. Legislative and executive actions should:

Strengthen whistleblower protections for law enforcement officers under NYS and NYC Human Rights Laws.

Prohibit retaliatory psychological referrals, reassignment, or health surveillance triggered by protected activity.

Mandate an independent review of all disciplinary actions following EIO, IAB, or misconduct complaints initiated by the affected officer.

Reform cannot happen when truth-telling is a liability and complicity is rewarded.

E. Public Accountability Through Data Transparency

Opaque systems breed impunity. To ensure meaningful reform, the City must:

Publish anonymized, disaggregated data on disciplinary outcomes, risk assessments, and subpoena activity by race, rank, gender, and command.

Expand the Administrative Code § 14-186 to include data on disciplinary overrides, sealed record references, and risk management referrals.

Create a civil rights settlement disclosure registry for all NYPD-related litigation to expose patterns of discrimination, harassment, and retaliation.

Just as budgetary transparency is essential to fiscal health, disciplinary openness is essential to constitutional policing.

F. Restore Constitutional Order to Internal Discipline

At its root, the NYPD’s disciplinary regime must be rebuilt around the core principles it currently undermines:

Due Process, meaning that discipline must be predictable, challengeable, and based on evidence, not proximity, rumor, or belief.

Equal Protection means that race, gender, and political disfavor must never determine the outcome.

Freedom of Association and Belief, meaning that officers cannot be punished for their identity, ideology, or silence.

A constitutional institution does not suppress dissent. It invites it. It does not punish difference. It protects it. And it does not fear the truth—it demands it.

X. The Reform Mandate: From Institutional Survival to Constitutional Renewal

The crisis within the NYPD’s disciplinary system is not the result of policy drift—it reflects structural deficiencies long embedded in the department’s approach to internal accountability. When rules are vague, records are misused, discretion is unreviewable, and discipline is shaped by politics rather than principle, injustice becomes procedural. In such a system, silence is survival, dissent is punished, and constitutional rights are conditional. Reform is not just necessary—it is urgent.

The challenge is not whether misconduct exists. It is whether the system can be trusted to confront it fairly. The data says no. The lawsuits say no. The officers forced out for protected speech, racial identity, or mere social affiliation say no. Every structural weakness described in this report—from AG 304-06(8)(c)’s ambiguity to the unchecked powers of §§ 14-115 and 14-137—threatens officer welfare and the legitimacy of the department itself.

The implications go beyond New York. The NYPD is not merely the nation’s largest police force—it is its most visible. Its practices shape national discourse, influence reform models, and export policies to jurisdictions across the country. When it weaponizes sealed records, abuses surveillance authority, or disciplines officers for ideological nonconformity, it does not act in isolation. It sets a precedent. It sets a precedent—reinforcing patterns of racial disparity, civil liberties erosion, and administrative overreach through internal mechanisms of control.

The public has a right to know how discipline is applied—and misapplied. Officers have a right to be judged by evidence, not innuendo. And the law must mean what it says: that due process, equal protection, and freedom of belief are not contingent on command favor or institutional optics.

Reform must be structural. It must be statutory. And it must be sustained. This means:

Amending the Administrative Code to eliminate opacity and enforce real-time data reporting;

Repealing unaccountable disciplinary statutes and replacing them with constitutional safeguards;

Criminalizing the use of sealed records for retaliatory purposes;

Empowering independent oversight bodies to investigate, report, and redress institutional wrongdoing;

And reestablishing the principle that public service does not require ideological surrender.

A police department that suppresses identity, discourages transparency, and rewards compliance over integrity risks losing public trust. Institutions earn legitimacy not through control, but through principled accountability.

If New York City is serious about justice, it must treat civil rights within the NYPD as a matter of public safety, institutional survival, and democratic fidelity. Otherwise, the department will not merely fail itself—it will continue to fail us all.