Summary:

Across the United States, police departments quietly spend billions in taxpayer dollars to settle lawsuits involving sexual harassment, discrimination, retaliation, and other civil rights violations—yet the public rarely sees the bill. This long-form commentary examines how civil rights settlements are routinely buried in opaque budget line items, how the lack of mandated transparency shields repeat offenders, and how this systemic secrecy erodes public trust and fiscal accountability.

Drawing on case studies from the NYPD and a national review of the ten largest U.S. police departments, the article exposes how structural opacity enables institutional betrayal while undermining sound governance. It calls for bold, enforceable legislation—modeled on federal EEO reporting frameworks—to require the public disclosure of settlement data, disaggregated by claim type, protected class, and post-resolution outcomes.

The conclusion is simple: You can’t fix what you don’t track, and the public should never be forced to pay for misconduct it cannot see.

Section 1: A Crisis Hidden in Plain Sight

Every year, public agencies across the United States quietly absorb hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars to settle lawsuits involving civil rights violations—sexual harassment, gender discrimination, retaliation, and other forms of workplace misconduct. These payments are often substantial, drawn from municipal budgets, yet the details remain largely invisible to the public footing the bill. The settlements resolve credible allegations brought by police officers, administrative staff, and civilians—individuals who report abuse from supervisors or colleagues. But even when public funds are used to settle such claims, there’s typically no obligation to tell the public who was involved, how often it happens, or whether anything has changed.

This silence is structural, not accidental. Unlike other forms of government spending, civil rights settlements are often buried in generalized budget line items—“judgments and claims,” “litigation reserves,” or “general liability”—without specifics. Even in jurisdictions with relatively open data policies, no national or statewide mandates are to track or publish this information systematically and disaggregated.

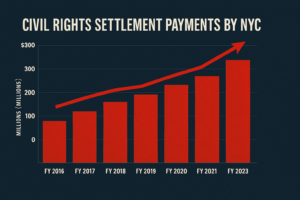

New York City, home to the nation’s largest police force, is a case in point. Between FY 2016 and 2023, the City likely paid well over $1.9 billion in tort settlements and judgments. The New York Police Department (NYPD) alone accounted for more than $1.3 billion of those payouts, year after year comprising over one-third of all City claims. In FY 2023, NYPD-related claims cost taxpayers $266.7 million—an astonishing sum that eclipses most departments’ budgets. And yet, we don’t know how much of that figure stems from gender discrimination, retaliation, or sexual harassment. We don’t see how many involved repeat offenders or higher-ranking officials. We don’t know how many survivors left public service or were driven out after speaking up.

This reporting gap represents a dangerous blind spot at a time when public agencies are expected to uphold the highest standards of conduct and fiscal stewardship.

Section 2: What We Know—and What We Don’t

What little the public knows about the most egregious abuses within the NYPD does not come from proactive transparency, internal reform, or official press releases—it comes from litigation, leaks, and investigative journalism. Take, for example, Captain Gabrielle Walls, a decorated Black woman officer and twenty-three-year NYPD veteran. Her lawsuit did not emerge because the department took accountability or issued a public reckoning. It became known only because she filed a suit in the New York State Supreme Court, naming the city of New York as defendants, Chief of Department Jeffrey Maddrey, Assistant Chief Scott Henderson, and Police Commissioner Edward Caban. According to the amended complaint, Walls alleges that after rebuffing an unwanted kiss from Assistant Chief Henderson during an on-duty encounter in September 2022—after years of sexualized remarks, grooming overtures, and suggestive behavior—she was passed over for multiple precinct command positions that were instead given to male colleagues with less seniority. She alleges that when she raised the issue, she was subjected to retaliation, including abrupt transfers, marginalization, and undermining her leadership credentials. None of this would be known if she, like many others, had been forced into a quiet settlement cloaked in a non-disclosure agreement. The allegations implicate the very top of NYPD’s command structure. Yet, absent public litigation, the institutional culture that protects those in power while punishing those who speak out would have remained intact and invisible. This is not a system designed for accountability—it is a system designed for concealment.

Officer Ann Cardenas’s case peeled back the curtain on what she described as a culture of unrestrained sexual degradation at Brooklyn’s 83rd Precinct. In a federal lawsuit filed in 2014, Cardenas alleged that her supervisor, Sergeant David John, groped her, kissed her without consent, simulated ejaculating on her, referred to her as his “work p***y,” and even bragged about masturbating to a Halloween photo of her dressed as Catwoman. When John retired, the harassment didn’t end—another officer, Angel Colon, allegedly continued the abuse, once telling her he would “rape her in a good way.” The City of New York declined to defend either officer. In a rare outcome, both were ordered to contribute to the $535,000 settlement—$20,000 from John and $15,000 from Colon—while the City paid the rest. In a scathing opinion, U.S. District Judge Ann Donnelly described the precinct’s environment as a “sordid frat house.” But as with so many others, this story reached the public only because Cardenas refused to be silenced. She litigated her case, rejected a confidential settlement, and endured years of legal warfare to ensure that the truth was exposed.

The same pattern emerges in other high-profile cases involving officers Shemalisca Vasquez, Lieutenant Angelique Olaechea, and Captain Sharon Balli—survivors who spoke out, faced retaliation, and only gained visibility because they fought their cases in court. Their experiences—and the public funds used to resolve them—would have remained invisible if they hadn’t.

Section 3: A National Pattern of Secrecy

This isn’t just a New York problem. Across the country’s top 10 largest police departments—responsible for policing tens of millions of Americans—operate with a comparable lack of transparency. Here’s what we know:

- NYPD (New York City): ~$11B budget; ~36,000 officers; $298M in FY23; $1.3B+ over eight years. Partial data from Comptroller reports, but not disaggregated.

- Chicago PD: ~$2.1B budget; ~11,700 officers; $107.5M in 2024; $384.2M from 2019–2023. No public database. Data is only available via FOIA and litigation.

- Los Angeles PD: ~$2.14B budget; ~9,100 officers; $215M over five years. Information only comes through lawsuits or budget hearings.

- Philadelphia PD: ~$877M budget; ~6,000 officers; $20.7M in 2022. Some data from Civil Rights Unit but no full transparency.

- Houston PD: ~$870M–$1.6B budget range; ~5,300 officers. Legal cost data is unknown—no comprehensive public reporting.

- Washington, D.C. MPD: $526M budget; ~3,900 officers. Lawsuit data scattered. Legal costs not regularly reported.

- Las Vegas Metro PD: $852M budget; ~3,300 officers. Settlement data unavailable.

- Dallas PD: ~$612M budget; ~3,100 officers. Legal cost data not tracked publicly.

- Phoenix PD: ~$540M budget; ~2,500 officers. $10.6M was reported in 2022. Budget line items are vague.

- Nassau County PD: ~$375M budget; ~2,400 officers. No data on settlements, even in detailed budget documentation.

This is a staggering pattern: Billions of public dollars are administered by agencies that face no meaningful transparency mandates regarding misconduct settlements. Most cities track workforce demographics under federal requirements, but the resulting liability is hidden when those employees face unlawful treatment.

Section 4: Why Existing Laws Fall Short

The United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) requires public employers to report demographic data under Title VII. These EEO-1 and EEO-4 reports provide valuable insights into hiring and representation trends, particularly for women, racial minorities, and other protected classes. But that’s where transparency ends. We know who gets hired, but we don’t know who faces harassment, discrimination, or retaliation once inside the workplace.

No federal law mandates the disclosure of settlements related to sexual harassment or civil rights violations. There is no requirement to break down these settlements by claim type or offender. While some states—like New York—have moved to restrict the use of non-disclosure agreements in sexual harassment settlements, loopholes remain. Informal pressure and retaliation can coerce survivors into silence. Legal departments continue to settle quietly and move on.

The absence of transparency laws is perilous in law enforcement agencies, where power dynamics, institutional loyalty, and union protections often create significant barriers to accountability. When cities and counties spend hundreds of millions annually on civil rights settlements, those figures should be audited and published—not buried.

Section 5: What Reform Could Look Like

To address this systemic opacity, Congress should authorize a new Component 2: Civil Rights Liability Disclosure report to complement existing EEO data collections. This biennial report would require all public employers—especially police departments—to report:

- The number and amount of settlements and verdicts related to sexual harassment, gender discrimination, retaliation, and other civil rights violations;

- Protected class categories involved (race, sex, disability, LGBTQ+);

- Officer rank and command (aggregated);

- Whether the officer was subject to disciplinary action or retained;

- Estimated legal defense costs and billable hours.

States can act independently. A Public Civil Rights Settlement Disclosure Act could require annual reporting from all public agencies, maintained by the State Comptroller or Attorney General. Such legislation would:

- Mandate disaggregated data by claim type, protected class, and department;

- Include a searchable database of payouts by agency;

- Require disclosure of post-settlement outcomes;

- Tie disclosure compliance to funding eligibility and accreditation.

Section 6: The Financial Argument

Transparency is not just ethical—it’s financially sound. In New York City, a projected model comparing the current litigation path with a transparency-based reform model shows potential savings of $395 million over six years. These savings stem from:

- Earlier interventions due to pattern recognition;

- Reduced repeat claims and misconduct by disciplined employees;

- Lower litigation defense costs and faster settlements;

- Risk-adjusted insurance premiums and improved municipal bond ratings.

Without accountability, settlements are treated as the cost of doing business—absorbed quietly, without consequence. With accountability, they become signals for reform, grounds for performance evaluation, and tools for prevention.

Section 7: The Human Cost of Silence

What little we do know about police misconduct rarely comes from internal transparency. It comes from lawsuits, whistleblowers, investigative journalism, and—in the most tragic cases—disasters too egregious to ignore. In April 2025, two NYPD officers from the Bronx pursued a stolen vehicle into Manhattan, despite a recently adopted department-wide policy limiting high-speed chases. After the suspect crashed and the car erupted into flames, the officers reportedly approached the wreck, then left the scene without rendering aid or calling for assistance. The man inside burned to death. The officers completed their shift and said nothing. The department only launched an investigation after the incident was leaked to the press. No internal alert. No timely disclosure. No accountability—until forced.

At the core of this conversation are not just policies violated but lives and careers irreparably harmed by unchecked misconduct. Survivors of discrimination and harassment face retaliation, demotion, blacklisting. Allies who speak up—who testify or support their colleagues—are themselves targeted. Whistleblowers are driven out of the profession altogether. The institutional reflex is not to reform but to bury. And yet, the truth keeps resurfacing—through court filings, public trials, and courageous journalism. Survivors shouldn’t have to endure years of legal warfare just to be heard. And taxpayers shouldn’t be footing the bill for secrets that shield repeat offenders.

This is not a failure of communication—it is a failure of accountability. A culture that protects the institution before the public and officers before integrity will always default to concealment. Unless the law mandates transparency, what we don’t see will continue to harm those within—and beyond—the badge.

Section 8: Structural Opacity and the Engineered Absence of Accountability

The concealment of police misconduct is not a byproduct of bureaucratic inefficiency—it is a design feature of the current system. In public safety institutions, especially law enforcement, the architecture of opacity has been deliberately constructed, brick by brick, over decades. The goal isn’t just to avoid bad press. It’s to control the narrative, suppress dissent, and insulate agencies from the systemic reform that transparency demands.

When officers engage in misconduct—whether it’s sexual harassment, racial discrimination, unconstitutional stops, or fatal neglect like the recent 2025 Bronx car chase that ended in a fiery death—the institutional response is rarely public reckoning. Instead, the default playbook contains, denies, and delays. Misconduct is buried in sealed settlements. Disciplinary proceedings are cloaked behind departmental privilege. Records are sealed, redacted, or “lost.” Internal investigations stretch for years with little to no resolution. And when settlements are finally paid, they are processed through opaque legal channels that shield the public from knowing who was responsible, what happened, or whether it was ever addressed.

There is no statutory mandate to report how often the same officer or unit is named in complaints or lawsuits, no requirement to disclose whether an accused supervisor has been promoted despite credible findings of misconduct, and no system to track which precincts accumulate the highest number of civil rights claims. This lack of disaggregation is not merely a failure of reporting—it is a refusal to govern in the light.

Consider the internal language often used in civil litigation by municipal legal departments. Cases are described as “nuisance suits,” even when they involve sexual assault or retaliation. Settlements are “cost-effective resolutions,” even when the payouts exceed the victim’s original demands. Rarely does the institution admit fault, and seldom does it initiate structural change in response. This strategy isn’t about legal prudence—it’s about reputation management. The institution’s image is protected at all costs, while the truth is quietly redacted.

This institutional muscle memory to suppress transparency isn’t confined to any jurisdiction. It is national in scope and normalized through legal practices that prioritize institutional defense over public interest. City law departments routinely negotiate settlements that include non-disparagement clauses, even when NDAs are legally limited. Agencies invoke exemptions in Freedom of Information statutes to shield disciplinary records, citing “ongoing investigations” that never close. Perhaps most egregiously, some departments have been known to reassign accused officers rather than discipline them—creating serial patterns of abuse that persist without consequence.

The absence of public-facing information about misconduct outcomes perpetuates what legal scholars call “institutional betrayal.” This is the idea that the structures created to protect employees and citizens—like EEO offices, internal affairs units, or inspector generals—end up reinforcing harm when they prioritize the institution’s image over the individual’s experience. When a survivor of harassment or discrimination watches her case get buried, her perpetrator promoted, and her career sidelined, the message is clear. This system is not designed to protect you.

It goes beyond the individual. This opacity corrodes democracy. It deprives the public of its right to evaluate public servants, policymakers of the data they need to legislate reforms, and marginalized communities of the protection they are disproportionately promised but rarely delivered. Accountability becomes impossible when the truth is systematically obscured, and injustice becomes predictable.

Let’s be clear: these failures aren’t just bureaucratic. They are budgeted. In many cities, settlements for police misconduct are pre-funded in annual appropriations or processed through municipal bond issuances. That means the cost of silence is embedded in the financial blueprint of the local government. There’s a line item for looking the other way. And there is no legal, economic, or political incentive to look closer.

These patterns will persist until we dismantle this culture of structural opacity and enact legal mandates that force open the black box. Agencies will continue to classify accountability as a PR problem rather than a governance obligation. Repeat offenders will remain untracked and unpunished. And public money will continue to bankroll silence.

The time for voluntary transparency is over. What’s needed now is rigorous, codified, and enforceable legislative intervention. Because what we don’t see, we don’t change. And the truth—delayed, denied, or buried—is still costing us every single day.

Conclusion: If You Don’t Track It, You Can’t Fix It

We cannot reform what we refuse to examine. And we cannot claim fiscal responsibility or institutional integrity while billions in public dollars are quietly spent to conceal, rather than correct, civil rights violations. The failure to disclose how, where, and why public agencies—especially law enforcement—settle claims of harassment, discrimination, and retaliation is not a minor oversight. It is a systemic failure of governance. A legal blind spot so large that it swallows accountability whole.

Every sealed settlement, every redacted report, every off-the-books reassignment represents more than a bureaucratic lapse. It represents the normalization of misconduct, funded by the people it harms. It signals to survivors that silence is the price of resolution. It tells perpetrators that misconduct carries no public consequence. And it tells taxpayers that their money can be spent shielding abuse without their knowledge, let alone their consent.

This is not how democratic institutions should function. It is the architecture of impunity—silent, sanctioned, and subsidized.

But this moment offers a chance to intervene. The infrastructure to do better already exists. We have federal frameworks like the EEOC’s demographic reporting system. We have procurement and compliance tools used in the private sector. We have legislative models in environmental law, securities regulation, and public health that prove what is possible when the government tracks risk transparently and acts accordingly.

What’s missing is not capacity—it’s political will.

It’s time for lawmakers to confront what years of litigation and press investigations have already made clear: voluntary transparency has failed. Institutions left to police themselves will default to secrecy. Public interest will remain subordinated to internal protection unless disclosure is mandated by law.

That mandate must be bold, national in scope, state-enforceable, and locally actionable. It must require agencies to disclose not just the dollars spent but the deeper patterns those dollars represent: repeat offenders, protected class categories, systemic retaliation, and the absence—or presence—of institutional accountability.

Transparency is not punishment. It is policy. It is how we re-align public institutions with the values they claim to serve, restore trust, prevent future harm, and ensure that financial responsibility does not come at the expense of human dignity.

No more redacted truths. No more silent payouts. No more pretending we don’t know what these numbers mean.

It’s time to open the books—not for spectacle but justice. If we can’t see the harm, we can’t stop it. We can’t change the culture if we don’t track the cost.

If we’re not willing to fix this now, we must ask ourselves: How much more are we willing to pay to protect silence?

Because the truth is simple: You can’t fix what you don’t track.

Eric Sanders, Esq. is a New York-based civil rights attorney and the president of The Sanders Firm, P.C. He advocates for transparency and accountability in public institutions and has represented hundreds of clients in litigation involving police misconduct, discrimination, and retaliation.

![A Financial Model for Reform [Public Reporting of Settlement Costs]](https://www.thesandersfirmpc.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/ChatGPT-Image-Apr-4-2025-05_39_04-AM-1024x683.png)