I. Introduction — Exclusion by Design

The promise of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act was not simply to make health insurance more affordable; it was to transform the very structure of health care access in the United States. It was framed as a historic leap toward universality, a moment when health care would finally be treated less as a privilege and more as a right. Politicians spoke in moral language. Economists spoke in actuarial terms. Lawyers spoke in statutory architecture. But buried in that architecture was a design choice — not an accident, not an oversight — that would determine who would live within the circle of coverage and who would be permanently left outside of it.

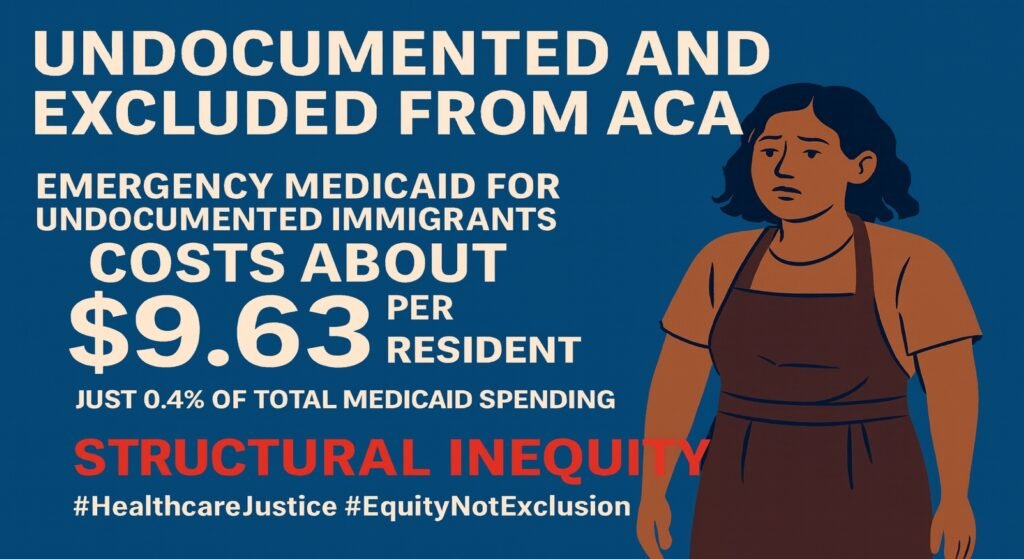

Millions of undocumented people live and work in the United States, paying taxes, raising families, and sustaining local economies. They cook in the restaurants we frequent, clean the offices in which we work, build the infrastructure we take for granted, and care for children and the elderly across neighborhoods. Yet, despite their contribution to the social and economic life of this country, they were categorically excluded from the core protections of the ACA. They cannot purchase health insurance through federal marketplaces, even at full price. They cannot receive Medicaid or Medicare. And, except in the most extreme emergencies, they cannot rely on public systems to meet even their most basic health care needs.

This exclusion was never about cost. In 2022 alone, undocumented immigrants paid an estimated $96.7 billion in taxes to federal, state, and local governments — $59.4 billion in federal contributions and $37.3 billion at the state and local level. More than a third of that money went directly to programs they are legally barred from accessing: $25.7 billion to Social Security, $6.4 billion to Medicare, and $1.8 billion to unemployment insurance. Their tax dollars keep the very public systems they are excluded from solvent. This is not a fiscal burden; it is structural extraction.

The result is a kind of silent segregation within the health care system. One group receives access to structured, regulated, and subsidized care. Another is pushed to the margins, surviving on a threadbare emergency safety net that was never designed to carry the weight of comprehensive health needs. Emergency Medicaid covers childbirth but not cancer treatment, dialysis but not routine checkups, catastrophic emergencies but not the quiet, cumulative illnesses that define daily life. The message is unmistakable: you can deliver your child here, but you cannot stay healthy here.

Behind every policy choice of exclusion is a story of who is deemed worthy of belonging. The ACA, despite its sweeping aspirations, built its structure on a definition of belonging that deliberately excluded millions. It did not have to be this way. It was a choice — a choice that continues to reverberate through hospitals, clinics, homes, and communities more than a decade later. It is a choice that fractures public health, inflates costs elsewhere in the system, and places the weight of political compromise on the backs of the most vulnerable.

Understanding this exclusion requires more than a moral argument; it requires confronting the legal, economic, and political architecture that sustains it. The exclusion of undocumented people from health care coverage is not an anomaly in American governance — it is a feature of how the state structures access, allocates resources, and defines the boundaries of legal personhood. It reflects not only how we deliver care, but how we define community itself.

This thought-piece examines that architecture directly — not as an abstraction, but as a legal and political mechanism with measurable human and institutional consequences. The story of the ACA’s exclusion of undocumented immigrants is, at its core, a story about how policy can function as a gate, a wall, and a weapon. It is a story about how civil rights, public health, and fiscal narratives collide. And it is a story about how those collisions reveal the underlying values of a nation.

II. Historical Context — Health Care, Immigration, and Structural Boundaries

To understand how exclusion became embedded in the ACA, it is necessary to step back into the long and uneasy relationship between immigration policy and the American health care system. For more than half a century, health access in the United States has been structured not simply by economic class, race, or geography, but by immigration status. This is not new. What the ACA did was not create this division but formalize and modernize it within a massive federal legislative framework.

The idea that health care access should depend on legal status is the legacy of a century of federal policymaking. Since the mid-20th century, programs like Social Security Act, Medicare, and Medicaid have been built with eligibility rules tethered to citizenship and lawful presence. These restrictions have always been political tools. They were used to shape public perception of who is “deserving” of social benefits and to shield lawmakers from accusations of extending the social safety net too broadly. The ACA was no different. The decision to exclude undocumented immigrants was not an afterthought but a direct continuation of a well-established legal pattern.

Emergency Medicaid emerged out of this very tension. It was created to satisfy the narrowest possible interpretation of legal and moral obligation: to pay for care only when a person’s life is in immediate danger. This approach was not designed to provide health care in any meaningful sense; it was designed to keep the state’s hands clean. Emergency Medicaid pays for childbirth, trauma care, and some forms of ongoing emergency treatment such as dialysis. It does not cover preventive care, chronic disease management, mental health services, or any of the basic medical infrastructure required to maintain long-term health. It was crafted as a stopgap, not a bridge.

By the time the ACA was drafted, the political landscape surrounding immigration had already hardened. Politicians understood that any legislation expanding health care access would become a lightning rod if it included undocumented immigrants. Instead of challenging that political orthodoxy, the architects of the ACA absorbed it. Undocumented people were explicitly written out of eligibility for Medicaid expansion, denied the ability to purchase plans on the ACA marketplace, and excluded from subsidies or tax credits. Their health needs were effectively outsourced to states, local governments, and safety-net hospitals already operating under immense strain.

This decision was defended as “necessary” to ensure passage of the bill. But that justification reveals the deeper structure at play: when faced with a choice between political expedience and equitable policy design, the political class chose expedience. The exclusion of undocumented people was the price paid to protect the broader ACA coalition. It was a calculated political trade — and like most political trades, the cost was borne by those without power at the negotiating table.

It is important to understand that this exclusion does not exist in isolation. It is nested within a broader system of structural boundaries — immigration laws, work restrictions, and public benefit limitations — that collectively function to keep undocumented people both economically indispensable and legally disposable. Their labor is accepted. Their taxes are collected. Their presence is tolerated. But their inclusion in fundamental social systems — health care among them — is deliberately withheld.

This is why the familiar cost argument deployed to justify exclusion from the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act rings so fundamentally hollow. It is not a statement of fiscal reality. It is political theater. The numbers themselves betray the performance. According to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, in 2022, undocumented immigrants paid an estimated $96.7 billion in taxes to federal, state, and local governments. That figure includes $59.4 billion in federal taxes and $37.3 billion in state and local contributions. Per capita, the undocumented population contributed roughly $8,889 per person, which means that for every one million undocumented people living in the United States, public services receive approximately $8.9 billion in additional tax revenue.

This is not a population “draining” the system. It is one of its under-acknowledged financiers. More than a third of these tax dollars — $33.9 billion — went directly into programs that undocumented workers are legally barred from accessing: $25.7 billion to Social Security, $6.4 billion to Medicare, and $1.8 billion to unemployment insurance. This is money that stabilizes the very social insurance systems that politicians claim must be “protected” from them. Undocumented immigrants fund a portion of these programs while being legally prohibited from receiving their benefits. In any other context, that would be recognized for what it is: structural inequity baked into fiscal policy.

State and local governments benefit as well. Nearly 40 percent of the total tax payments came through state and local revenue streams, the bulk through sales and excise taxes. These taxes are unavoidable. Every time undocumented residents purchase food, clothing, fuel, or other goods, they contribute to the infrastructure of their communities. Another significant share comes from property taxes — both from homeowners and renters — and personal and business income taxes. In fact, in 40 states, undocumented immigrants pay higher effective state and local tax rates than the top one percent of income earners. Their economic contributions are not marginal. They are embedded into the very revenue streams that keep state and local governments afloat.

The concentration of tax revenue in certain states only sharpens the point. California alone collects approximately $8.5 billion annually from undocumented taxpayers. Texas collects $4.9 billion. New York receives $3.1 billion. Florida, Illinois, and New Jersey each collect more than a billion dollars. These figures are not speculative. They reflect actual, measurable, recurring contributions to public budgets. Without them, state and local revenue shortfalls would be immediate and consequential.

This makes the “cost” narrative particularly perverse. Politicians who invoke it are not describing an economic problem. They are defending a political arrangement: an arrangement that accepts undocumented labor, collects undocumented tax contributions, and then withholds full participation in the very systems those dollars support. Their tax money is welcomed; their health and dignity are not. It is an architecture of extraction without reciprocity, an unspoken social contract that demands contribution but denies inclusion.

This historical context dismantles the convenient fiction that the ACA’s exclusion of undocumented immigrants was an administrative or budgetary inevitability. It was not. It was a deliberate policy decision layered onto an already exploitative fiscal structure. The exclusion was not about affordability; it was about who is allowed to belong to the public good. Undocumented immigrants are not fiscal liabilities. They are net contributors to the public systems from which they are deliberately excluded. That reality does not reflect an economic necessity. It reveals, as every chapter of this long story has revealed, the true location of the barrier: not in the nation’s fiscal capacity, but in its political will.

III. The Legal Architecture of Exclusion

Exclusion from health care coverage is not an accident of implementation. It is a product of law. The exclusion of undocumented people from the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) is codified through a lattice of statutes, regulations, and administrative directives that do not merely ignore undocumented communities — they explicitly wall them off. This is not a loophole. It is a deliberate legal design.

The ACA, when enacted in 2010, made expansive changes to the federal health care system. It restructured the individual market, expanded Medicaid in participating states, and created federally subsidized marketplaces to make coverage affordable. But at the heart of this new structure was a categorical bar: undocumented immigrants were denied access to Medicaid expansion, prohibited from purchasing insurance on the ACA exchanges even at full cost, and excluded from premium tax credits and cost-sharing subsidies. They are invisible in the ACA’s coverage architecture by statutory design.

This exclusion is not unique to the ACA; it reflects the legal inheritance of programs like Medicare and Medicaid. Since their inception in the 1960s, federal health programs have tied eligibility to citizenship or lawful presence, embedding immigration status as a legal boundary for public goods. The ACA simply extended and modernized this boundary in the language of “coverage reform.” This means undocumented people are not just uninsured — they are legally prohibited from participating in the very system their labor and tax contributions help sustain.

The legal structure of exclusion is reinforced through complementary laws and regulations. Federal guidance bars undocumented people from using health insurance marketplaces. Immigration statutes prevent them from obtaining lawful status that would unlock access. Public benefits laws frame eligibility not as a question of need but of legal status, creating a statutory fiction: that those without status are also without claim. These are not neutral legal classifications. They are policy choices that define who counts as a full participant in the administrative state.

This structure operates with brutal efficiency. Undocumented immigrants pay into the system — in 2022, contributing nearly $97 billion in taxes — but the law treats their contributions as a one-way street. $25.7 billion flowed into Social Security, $6.4 billion into Medicare, and $1.8 billion into unemployment insurance, programs they are legally barred from accessing. In any other context, this would be recognized as taxation without representation. Here, it is dressed up as policy orthodoxy.

This legal structure also serves a political function: it shields the state from accountability while preserving the fiscal benefits of undocumented labor. By excluding undocumented immigrants from coverage, the federal government avoids the budgetary appearance of expanded entitlements. But by accepting their tax contributions, it stabilizes public programs with revenue extracted from those who will never benefit from them. This dual structure allows politicians to stand at a podium and decry the “cost” of undocumented immigrants while quietly depositing their contributions into the Treasury.

The deeper legal problem is not simply exclusion. It is that exclusion has been normalized as lawful governance. Immigration status has been transformed into a legal boundary line for fundamental social goods. Access to health care is no longer merely a matter of need, or even of payment; it is a matter of legal belonging. Undocumented people live inside the economy but outside the law’s promise of shared protection.

This is why the legal architecture of exclusion must be understood not just as health policy, but as a civil rights structure. It determines who is protected by administrative continuity and who is deliberately made precarious. It defines who is allowed to build a reliance interest in public institutions and who is perpetually vulnerable to political winds. And it ensures that those most vital to the nation’s economic functioning are structurally prevented from sharing in the public goods they help sustain.

IV. The Cost Myth

If the legal structure supplies the boundary, the cost myth supplies the cover. For decades, fiscal rhetoric has been used to mask exclusionary policy choices, particularly in immigration and health care. Politicians argue that including undocumented immigrants in health coverage would be “too expensive,” that it would “burden taxpayers,” that the nation “can’t afford it.” These are not neutral budgetary assessments. They are narrative devices — talking points designed to provide a veneer of fiscal responsibility to what is, at bottom, a political decision to exclude.

The myth collapses as soon as it meets the facts. In 2022 alone, undocumented immigrants contributed $96.7 billion in taxes. That’s $8,889 per person in federal, state, and local revenues. This money flows into the same systems they are locked out of. Far from being a fiscal drain, undocumented immigrants are net contributors. And more than a third of their contributions go into federal social insurance programs from which they receive nothing in return. They subsidize a system that denies them entry.

This reality exposes the “cost” argument for what it is: a political pretext. If inclusion were truly a question of dollars and cents, then the debate would center on how to equitably allocate a funding stream that already exists. Undocumented taxpayers are not outside the system; they are inside it, underwriting it, making it solvent. Yet politicians speak as though their inclusion would be some radical new expense, rather than an acknowledgment of their already substantial investment.

The cost myth is also strategically timed and targeted. It tends to surface during budget cycles, election seasons, and moments of legislative negotiation. It allows political actors to signal fiscal toughness while deflecting from the structural truth: that exclusion does not reduce costs. It merely shifts them. When undocumented immigrants are excluded from primary and preventive care, they are forced into emergency rooms and safety-net hospitals. This creates downstream costs for states, localities, and providers — costs that are diffuse, untracked, and politically invisible. Exclusion turns a shared responsibility into a hidden tax on public hospitals and local communities.

This fiscal redistribution also maps neatly onto racial and socioeconomic lines. The communities most impacted by the exclusion of undocumented people are disproportionately Black, Latino, and Asian immigrant communities. They bear not only the health consequences but also the economic strain when medical costs are shifted downward. This isn’t an unintended consequence. It’s the point. The cost myth doesn’t just justify exclusion; it entrenches it by locating the burden where resistance is weakest.

In fact, states with the largest undocumented tax contributions are the same states that bear the brunt of exclusionary health policy. California collects $8.5 billion annually from undocumented taxpayers, Texas $4.9 billion, New York $3.1 billion. These contributions sustain state and local budgets. Yet the residents who provide that revenue are denied basic access to the health care system they help fund. In effect, exclusion becomes a mechanism of fiscal extraction: money flows up, care does not flow back down.

This is why the fiscal narrative surrounding undocumented health care is not a debate over resources. It is a debate over belonging. The claim that “we can’t afford to cover undocumented people” is not a factual statement. It is an ideological marker — a way of asserting who is inside the polity and who must remain outside. By keeping the conversation framed in cost terms, political actors obscure the underlying structure of exploitation.

The ACA did not invent this myth. It inherited it. But by hard-coding exclusion into federal law, it gave the myth a new legal foundation and a renewed political afterlife. The cost myth remains effective precisely because it sounds plausible. It invites the public to imagine inclusion as a new expense rather than acknowledging the quiet, ongoing subsidy already being paid by undocumented communities. It shifts the moral and political burden of justification away from the state and onto those excluded.

To dismantle this myth, one has to name it plainly. The exclusion of undocumented immigrants from health coverage is not an act of fiscal prudence. It is a political choice designed to preserve a structure of unequal belonging. It is not about what the country can afford. It is about who the country chooses to count.

V. Civil Rights in the Shadow of Exclusion

The exclusion of undocumented immigrants from health care is not just a policy gap; it is a structural civil rights issue. It is the quiet denial of access to a fundamental human need — one embedded in law, justified by myth, and perpetuated through the machinery of government itself. This exclusion shapes the contours of personhood in the United States, drawing hard lines around who is recognized by the state and who is functionally invisible to it.

American civil rights law has always existed in tension with the concept of conditional personhood. Legal protection in the U.S. has often hinged on membership — who counts as part of the polity, who can claim equal protection, who is entitled to state-administered benefits. While undocumented people are not stripped of all constitutional protections, they are strategically denied access to the basic infrastructure that makes those rights meaningful. A right without institutional scaffolding is a right that can be ignored.

Health care sits at this intersection with particular force. Access to medical treatment is not merely a transactional benefit; it is what enables individuals to live, work, parent, and exist with dignity. Excluding entire communities from that infrastructure effectively creates a second-class legal status — one not officially declared but thoroughly operationalized. It produces a caste of workers who pay into the system but are barred from its protections, whose labor is essential but whose personhood is negotiable.

This civil rights dimension is often obscured by the way health policy is discussed in Washington. Coverage is framed as a matter of budget lines and eligibility categories rather than of equal protection and human dignity. But civil rights law has always been about more than formal equality — it is about substantive access. A structure that allows one group to live with institutional protections while forcing another to rely on emergency rooms and charity care is not neutral. It is a hierarchy, maintained through law.

The exclusion also deepens racialized inequities. The overwhelming majority of undocumented immigrants in the United States are people of color. They live in communities already bearing the weight of underfunded schools, over-policed streets, environmental hazards, and economic insecurity. Denying health care access compounds those structural disadvantages, ensuring that these communities remain precarious. It is not coincidental that this exclusion dovetails with other mechanisms of control: housing insecurity, limited labor protections, and heightened vulnerability to state surveillance. When policymakers say health care access “should be reserved for citizens,” they are not just drawing a bureaucratic line — they are reinforcing a racialized caste structure.

The fiscal architecture reinforces this inequity with precision. Undocumented immigrants contribute billions to public programs, including $25.7 billion annually to Social Security Administration and $6.4 billion to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, yet they are legally barred from reaping the benefits. Their tax contributions help ensure that those programs remain solvent for others — including those who politically argue against their inclusion. That is not simply economic exclusion. It is the state using legal status as a tool to extract value without recognizing the full humanity of those who provide it.

This is why exclusion from health care must be understood not as a budgetary or administrative matter, but as an extension of the civil rights struggle itself. It raises the same essential question that has animated civil rights battles throughout American history: Who counts? Who belongs? Who gets to benefit from the public systems their labor sustains?

VI. The Institutional Toll of Destabilization

When the state builds exclusion into the foundation of its health care system, it does not only harm undocumented individuals and their families. It destabilizes entire institutions. Exclusionary health policy doesn’t remain neatly contained within a single group — it cascades outward, undermining the infrastructure of hospitals, clinics, local health departments, and the public health system at large.

Emergency Medicaid is the clearest example of this. It was never intended to function as a substitute for comprehensive care. It was created as a narrow, short-term safety valve to cover medical emergencies, labor and delivery, and certain acute treatments. Yet for millions of undocumented people, it functions as the only form of public coverage available. This is not a safety net; it’s a pressure point — and it is cracking under the weight of political design.

Because undocumented patients are systematically excluded from preventive and primary care, hospitals and clinics end up absorbing delayed, more expensive interventions at later stages of illness. Treatable conditions become emergencies. Manageable diseases become chronic crises. This imposes a financial and operational burden on safety-net hospitals — many of which operate with thin margins and serve communities already facing care shortages. The cost isn’t eliminated by exclusion; it’s redistributed and amplified.

This burden is especially pronounced in states with high undocumented populations, such as California, Texas, New York, Florida, Illinois, and New Jersey. These are the same states where undocumented taxpayers contribute the most to public revenue — California alone collects $8.5 billion annually — yet their exclusion from coverage drives up uncompensated care costs for hospitals and local governments. The state gets the revenue, but hospitals get the bill.

This structural contradiction undermines institutional stability in several ways:

Financial destabilization: Safety-net providers face mounting uncompensated care costs, jeopardizing their ability to remain solvent. These costs often lead to cutbacks in services that affect all patients, not just undocumented ones.

Operational strain: Hospitals become emergency care providers of last resort, diverting resources from preventive care and chronic disease management to crisis response.

Public health degradation: Preventable outbreaks, unmanaged chronic conditions, and fragmented care undermine population-level health goals — including those set by the federal government itself.

This is the quiet cost of exclusion — not seen in budget projections but felt in emergency rooms, clinic wait times, and health outcomes across entire communities. When the health system is forced to function with deliberate exclusion baked into its design, it loses its ability to operate predictably. Planning becomes guesswork. Safety nets become fiscal shock absorbers. Institutions begin to fray.

And it isn’t just health institutions that bear the burden. Exclusion distorts policy accountability itself. By hiding costs in hospitals and local budgets, federal and state governments obscure the true price of exclusionary policy from the public. They preserve the political narrative of “cost control” while quietly offloading the bill to the very institutions tasked with caring for the excluded. It’s an accounting trick with real human consequences.

This dynamic doesn’t just weaken health systems; it erodes public trust. When communities see hospitals overwhelmed, services cut back, and care delayed, they don’t parse out the fiscal mechanics of exclusion. They lose faith in the system as a whole. That erosion of trust doesn’t stay confined to immigrant communities. It spreads — weakening the connective tissue of public health governance.

The exclusion of undocumented immigrants from health care is therefore not merely a moral failure. It is a structural destabilizer. It undermines the fiscal and operational foundation of the institutions on which everyone relies. In the name of “controlling costs,” it quietly creates a system that is both more expensive and less stable.

VII. Weaponized Exclusion as Political Strategy

The legal exclusion of undocumented immigrants from the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) did not simply happen. It was not some inadvertent policy oversight buried in the footnotes of legislative text. It was a decision — one forged in the heat of political negotiation, justified through fiscal pretext, and sustained because it became an extraordinarily useful instrument of political power.

Exclusion functions as a pressure valve. It gives lawmakers the ability to speak about universalism without having to build it. It allows politicians to perform moral ambition — “affordable care for all” — while leaving intact the legal and political barriers that keep millions of people outside the system. And because undocumented immigrants have been historically excluded from the most visible channels of political participation, this design offers enormous political upside with almost no electoral cost.

The bipartisan utility of exclusion

In the early debates over health care reform, exclusion of undocumented people was not contested policy; it was a baseline assumption. During the legislative debates leading up to the ACA’s passage in 2010, both major political parties treated the question of inclusion as radioactive. The right viewed inclusion as political heresy, to be used as a weapon against the bill’s supporters. The center-left, fearing the collapse of the entire legislative package, accepted exclusion as the price of passage.

That acceptance calcified into policy. Once written into law, the exclusion gained a kind of statutory legitimacy. Even after ACA implementation, few mainstream politicians were willing to revisit the exclusion. It was politically safer to reinforce it than to challenge it. And over time, this silence became its own strategy: what is not contested becomes normal.

This is the mechanics of weaponization. When a policy choice becomes politically useful — as exclusion has — it ceases to be merely about what is written in law. It becomes a tool. Politicians can pick it up, invoke it, sharpen it, or wield it depending on the climate of the moment. When the goal is to signal fiscal restraint, exclusion is dressed up as budgetary prudence. When the goal is to stoke populist resentment, exclusion is recast as a shield against an imagined flood of “unearned benefits.” And when the goal is simply to avoid hard governance, exclusion sits quietly in the background, requiring no new action but preserving its political utility.

Political narratives that sustain exclusion

What makes this strategy particularly insidious is how deeply it has been woven into public narrative. Decades of political rhetoric have trained the public to associate undocumented immigrants with cost, strain, and burden. Even when those associations are factually false — and the $96.7 billion in annual tax contributions from undocumented immigrants makes that abundantly clear — they are politically effective. A talking point repeated long enough becomes a reflex.

Exclusion also serves as a proxy battlefield. Rather than engage with the broader failures of the American health care system — its fragmentation, its dependence on employer coverage, its cost inflation, its inequities — politicians can redirect anger toward those who are legally excluded. The public is encouraged to view undocumented immigrants not as fellow contributors but as outsiders, competitors for scarce resources. The underlying system remains untouched, its inequities shielded by a carefully constructed narrative of blame.

And because undocumented immigrants are structurally vulnerable — unable to vote, often afraid to speak, dependent on industries that offer little protection — they are the perfect political foil. No constituency can push back more quietly than one without political power.

Exclusion as a renewable political resource

Exclusion’s endurance is not only rhetorical. It functions as a renewable resource in political cycles. Every few years, a new wave of debates emerges: over budgets, health care access, immigration policy. And every time, the same lines are redrawn: who belongs, who doesn’t, who “deserves” coverage, who “costs” the system money. The legal exclusion embedded in the ACA doesn’t just sit in statute books. It reanimates itself every election season as a political weapon ready for use.

This is why reforms that rely solely on administrative discretion are insufficient. So long as exclusion remains a politically exploitable structure, it will continue to distort the national debate. Politicians can reap the benefits of fiscal extraction — $25.7 billion annually in Social Security contributions, $6.4 billion to Medicare, and billions more to state and local revenues — while claiming moral and fiscal high ground for maintaining the very exclusion that makes those extractions possible.

The rhetorical sophistication of weaponized exclusion

The modern exclusionary narrative is rarely framed in explicit xenophobic language anymore, at least not in formal policy spaces. Instead, it’s cloaked in technocratic euphemisms: “eligibility standards,” “fiscal sustainability,” “coverage priorities.” This sanitized language masks the moral violence of exclusion behind the neutral tone of policy management. It allows legislators and agency officials to defend exclusion not as bigotry, but as “responsible governance.”

This is what makes weaponized exclusion so difficult to uproot. It is not shouted from podiums; it is whispered through budget markups, actuarial models, and eligibility definitions. It is embedded in the quiet bureaucratic assumption that universality is always too expensive, that belonging must be rationed, and that some lives can be safely left at the margins.

The cost of political expediency

Weaponized exclusion has consequences that extend far beyond the health care system itself. By maintaining this structure, political actors teach the public to accept exclusion as rational. Over time, what began as a political compromise hardens into a moral ceiling. The idea of including undocumented people in health care coverage stops being viewed as a policy question and becomes framed as a political impossibility.

This is how inequality becomes structural: not through dramatic acts of cruelty, but through quiet acts of convenience.

VIII. The Chilling Effect on Governance

When exclusion becomes politically useful, governance itself bends around it. It is not just health care that gets reshaped — it’s the entire administrative posture of the state. Institutions learn to avoid the politics of inclusion. They learn that designing policy for everyone — truly everyone — is risky. And so, the very capacity for equitable governance begins to atrophy.

Governance under the shadow of political volatility

Health agencies, hospital systems, and local governments operate in an environment where immigration policy is perpetually volatile. Administrators understand that extending even modest coverage protections to undocumented people can trigger legislative backlash, budgetary retaliation, or public uproar manufactured by political actors who have mastered the art of turning exclusion into spectacle. So, they calibrate their actions accordingly.

This is not theoretical. Across the country, hospitals have adopted internal protocols to limit the visibility of services provided to undocumented patients. Local governments hesitate to expand programs for fear of becoming political targets. Even state agencies sympathetic to inclusion tread carefully, designing programs with intentional administrative ambiguity to avoid drawing attention. The chilling effect is so pervasive that it shapes what never even gets proposed.

Policy imagination constrained by fear

This chilling effect corrodes policy imagination. When policymakers are taught that inclusion is politically dangerous, they stop imagining universal solutions altogether. Entire categories of residents are simply left out of early policy design processes. Eligibility criteria are drawn narrowly not because there is no fiscal capacity, but because political fear dictates the boundaries of who counts.

This constrained imagination leads to structurally fragile systems. For example, Emergency Medicaid — a program never designed for long-term coverage — ends up carrying the weight of millions of people’s health needs. Community health centers stretch themselves thin trying to cover gaps left by deliberate policy omission. And hospitals, under constant financial pressure, are forced to function simultaneously as care providers and fiscal buffers for state exclusion.

Institutional incentives and silent complicity

The chilling effect also distorts institutional incentives. Public health agencies and safety-net institutions know that challenging exclusion directly could bring political or financial reprisal. So they adapt by internalizing the exclusion as a fixed parameter. Over time, they become silent accomplices to the very policies that undermine their mission.

This complicity is not born of malice. It is born of survival. But it ensures that exclusion never faces institutional resistance. Instead, it is absorbed, normalized, and operationalized into the day-to-day functioning of governance. Exclusion, in effect, becomes an unspoken administrative constant.

Accountability dissolved through fragmentation

Another defining feature of this chilling effect is how it dissolves accountability. The costs of exclusion are real — but they are scattered. A hospital absorbs uncompensated care here. A county clinic loses staff capacity there. A local budget faces quiet shortfalls. No single agency or actor can be blamed. This fragmentation of harm makes exclusion politically durable: everyone bears the cost, but no one can point to where it begins.

And because no single actor “owns” the exclusion, it becomes nearly impossible to mount a coordinated institutional challenge. The state benefits from the revenue extracted from undocumented communities. Health systems carry the burden. And the political class sustains the fiction that nothing can be done.

Community fear as administrative design

Perhaps the most insidious aspect of this chilling effect is the psychological governance it produces within undocumented communities themselves. People who live under the constant threat of deportation or legal scrutiny learn quickly that engaging with state systems can be dangerous. They delay care, avoid applying for services, and sometimes forgo treatment entirely.

This fear is not accidental. It is a predictable byproduct of exclusionary policy design. It ensures that undocumented people self-select out of systems that already exclude them, further reinforcing their invisibility in policy debates. Their absence from administrative data is then used to justify their exclusion — a circular logic that sustains itself without explicit enforcement.

Governance without courage

When governance operates in the shadow of political fear, it loses its capacity to lead. Policy becomes defensive, reactive, and timid. Programs are designed for minimum controversy rather than maximum equity. Data collection becomes selective. Outreach becomes muted. And the result is a public system built on managed avoidance — a structure designed not to solve a problem but to keep it politically quiet.

This is the governance landscape that exclusion has built. It is not one of active cruelty, but of systemic cowardice — a bureaucracy that has learned to survive by looking away.

IX. Beyond Cost: The True Price of Exclusion

The cost myth was never about cost. It was about control. It was about creating a narrative architecture that justified exclusion without ever having to defend it on moral or legal grounds. Politicians didn’t need to make explicit arguments about worthiness; they only needed to gesture toward the ledger. But ledgers can lie — or, more accurately, they can be written to conceal truth. And for decades, the health care debate in this country has relied on that concealment.

To talk honestly about the cost of undocumented immigrants in the health care system requires one to first confront the fiscal asymmetry that sustains it. Undocumented people contribute $96.7 billion annually in taxes to federal, state, and local governments. They pay payroll taxes for programs they cannot access — $25.7 billion to Social Security Administration, $6.4 billion to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, $1.8 billion to unemployment insurance. They pay state and local sales, property, and income taxes that fund public hospitals, infrastructure, and schools. They do not receive an equivalent return on that investment.

This is the first, fundamental truth: undocumented people are net contributors, not drains. The cost myth inverts this reality, deliberately. It frames the excluded as a burden to justify continuing to exclude them, ensuring that their contributions remain politically invisible.

The shifting of costs, not their elimination

Exclusion doesn’t eliminate costs. It shifts them — downward, sideways, invisibly. Every emergency room visit by someone without access to primary care, every late-stage diagnosis of a preventable disease, every maternal health crisis exacerbated by lack of prenatal care — these are not costs that vanish into thin air. They are costs absorbed by public hospitals, municipal budgets, and local communities.

This redistribution is intentional. By keeping undocumented people excluded from structured coverage, federal and state governments can posture as fiscally responsible while offloading the actual cost of care onto institutions least able to bear it. Hospitals become de facto insurers of last resort, absorbing uncompensated care. Counties stretch public health budgets to cover emergencies they did not cause. Charitable clinics fill gaps they were never meant to sustain. And through it all, political actors continue to claim that inclusion is “too expensive.”

It is a neat trick: extract billions in tax revenue from undocumented communities, deny them access to coverage, then make hospitals, counties, and poor municipalities clean up the mess. The costs are real, but because they are dispersed, they become politically invisible.

The human cost behind fiscal fictions

The second, equally fundamental truth is that exclusion is not an abstraction. It is measured in illness, in fear, and in death. Exclusion ensures that many undocumented people will forgo preventive care entirely. It ensures that manageable conditions — hypertension, diabetes, asthma, chronic pain, cancer — are allowed to worsen until they become catastrophic. It ensures that undocumented pregnant women walk into emergency rooms without having had a single prenatal visit. It ensures that treatable mental health crises become chronic, destabilizing emergencies.

And because the exclusion intersects with race, class, language, and labor exploitation, it compounds existing inequities. The communities bearing this weight are often the same communities already contending with environmental injustice, economic precarity, and over-policing. When health care is structurally denied, the ripple effects extend far beyond the hospital walls: they shape how entire neighborhoods experience illness, labor, and state power.

The cost myth flattens these human consequences into budget lines, if it acknowledges them at all. But they are there — in overburdened safety-net systems, in maternal mortality statistics, in the widening racialized gaps in life expectancy.

The corrosive effect on the health system as a whole

The third truth is institutional. Exclusion corrodes the entire health care system, not just the margins. It makes the system more chaotic, more expensive, and less rational. When millions of people are forced to access care through emergency rooms rather than structured systems, health planning becomes guesswork. Preventive interventions are underutilized. Chronic conditions are left to spiral. Costs rise.

Moreover, exclusion undermines the fiscal stability of the very safety-net institutions meant to serve everyone. Hospitals serving large immigrant populations operate under constant financial stress. When they are forced to subsidize care for the excluded without structural support, their ability to provide services to the broader public is eroded. The system’s most fragile components are forced to absorb the shock, creating instability that eventually reaches everyone.

This is why exclusion, though politically framed as a marginal issue affecting a specific population, is in fact a structural weakness in the entire system. It destabilizes hospitals. It distorts budgets. It breaks the logic of preventive care. It undermines equity goals. It hollows out universality itself.

The civic cost: exclusion as democratic fracture

But perhaps the most corrosive cost is civic. When a government knowingly extracts from a population while excluding them from protection, it delegitimizes its own claim to democratic governance. It creates a two-tiered social contract: one for those recognized as full members of the polity, and another for those rendered invisible except as sources of labor and revenue.

This fracture does not remain contained within immigrant communities. Over time, it erodes public trust in governance itself. When institutions are built to exclude, when laws are written to create deliberate inequality, it teaches the public that universality is a lie — that government does not serve all, only some. And when trust collapses, systems become brittle. Public health becomes reactive rather than proactive. The legitimacy of shared governance erodes.

The “cost” of including undocumented immigrants in health care is therefore not a fiscal threat. It is a moral, institutional, and democratic necessity.

X. Reclaiming Universalism: The Path Forward

The exclusion of undocumented immigrants from the ACA is not immutable. It is not divine law. It is a political choice, and like all political choices, it can be undone. But undoing it requires clarity — clarity about how exclusion functions, who benefits from it, and what it costs. It also requires a commitment to something that has been in short supply in American health policy: political courage.

Naming the reality, not the myth

The first step toward change is to name the exclusion plainly. Undocumented immigrants are not fiscal drains. They are taxpayers, workers, caregivers, community members — integral to the social and economic life of the nation. Their exclusion from health care coverage is not a technical necessity. It is a political decision designed to preserve a convenient fiction about scarcity.

Naming the reality also requires dismantling the language of technocracy that has shielded this exclusion from scrutiny. Terms like “eligibility standards” and “fiscal prudence” are often used to sanitize what is, at its core, a decision to deny people access to health and dignity. Language matters. As long as exclusion is described in bureaucratic terms, it will continue to be treated as policy rather than as state-sanctioned inequity.

Policy tools exist — what’s missing is will

The policy mechanisms to include undocumented immigrants in health care already exist. States like California and Illinois have begun to expand Medicaid coverage to undocumented adults using a mix of state funds and creative administrative strategies. Others have built state-based coverage programs designed to fill the federal gap. These are not perfect solutions, but they demonstrate that exclusion is a choice, not an inevitability.

At the federal level, Congress could remove the statutory bar on ACA marketplace participation for undocumented immigrants. It could authorize states to use federal funds to cover undocumented residents, or create new universal coverage models that decouple immigration status from eligibility. None of this requires inventing a new system from scratch. It requires the political will to use the system we already have differently.

Transparency as a disruptor

One reason exclusion has remained politically durable is that the fiscal flows are hidden. The $96.7 billion that undocumented immigrants contribute annually is not tracked in a way that makes its relationship to exclusion visible. Hospitals quietly absorb costs. Counties quietly plug holes. The public never sees the full picture.

Mandating transparent accounting of both contributions and costs would dramatically alter the political conversation. When the public sees that undocumented communities are net funders of the very programs they’re excluded from, the cost myth begins to crumble. Transparency does not guarantee justice, but it removes the cover under which injustice thrives.

Civil rights and the logic of inclusion

Reclaiming universalism is not just about fiscal policy. It is about civil rights. It requires framing health care not as a transactional good, but as a public obligation tied to human dignity. Undocumented immigrants live and work within the borders of this country. Their labor sustains its institutions. To deny them access to health care is to affirm a hierarchy of belonging that is antithetical to democratic principles.

This is why legal strategies may also matter. Litigation that challenges exclusion as a violation of equal protection or civil rights norms can help expose its underlying logic to judicial and public scrutiny. While courts have historically given wide deference to Congress on immigration matters, sustained legal and public pressure can help reshape the boundaries of what is politically imaginable.

Political courage and universalism

In the end, none of these strategies will matter without political courage. Exclusion persists not because it is rational but because it is politically convenient. Reclaiming universalism means making the uncomfortable argument in public: that universality cannot coexist with exclusion, that a health care system that depends on extracting from some while excluding them is structurally illegitimate.

It means confronting the quiet coalition that sustains exclusion — fiscal conservatives who hide behind cost myths, moderates who accept it as a political necessity, and bureaucrats who manage it as a technical constraint. It means treating inclusion not as a radical idea but as a baseline obligation of a functioning democracy.

A more honest future

Reclaiming universalism is not just about health care. It is about reasserting the idea that public goods belong to all who contribute to them. It is about rejecting the legal fiction that some people can exist inside the economy but outside the protections of the state. It is about rebuilding trust in governance itself, not through slogans, but through material guarantees.

The ACA’s exclusion of undocumented immigrants was a political compromise dressed as policy. It does not have to be permanent. The path forward is clear — transparency, legal challenge, policy redesign, and political will. What remains is the collective courage to walk it.

Because in the end, a nation that claims to care for its people must decide who counts as its people. And if it chooses to exclude those who help sustain it, then the exclusion will define not only them, but us.