Executive Summary

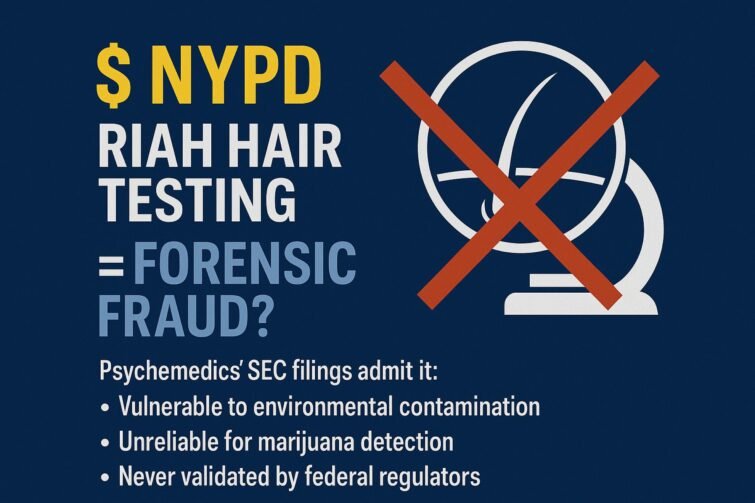

Despite persistent scientific controversy and the lack of regulatory approval from any federal workplace drug testing authority, employers across the public and private sectors continue to rely on Psychemedics Corporation’s Radioimmunoassay of Hair (RIAH) drug testing to make high-stakes employment decisions. From terminations to promotion denials, RIAH test results are often treated as definitive proof of misconduct—yet Psychemedics’ own SEC filings reveal unresolved contamination risks, misleading claims of validation, and persistent scientific uncertainty, all of which seriously undermine the reliability of these tests.

This thought leadership article draws on a side-by-side analysis of Psychemedics’ 2003 and 2025 Form 10-K reports, demonstrating how the company’s public narrative evolved from cautious technical disclosure to selective reassurance. It argues that continued reliance on RIAH testing, especially in civil service and safety-sensitive contexts like the NYPD, exposes employers to significant legal, constitutional, and reputational risk.

Key findings include:

Contamination remains a known and unresolved threat. In 2003, Psychemedics admitted that external contamination required mitigation and that simpler washes (like methanol) were inadequate. The company acknowledged that its proprietary extended wash was “a conservative policy in removing and accounting for external contamination.”

By 2025, that candid language will disappear. Instead, Psychemedics relies solely on a 2014 FBI study involving cocaine under laboratory conditions. This study has not been replicated, only addressed a single drug, and was never intended to validate multi-substance generalizability. The 2025 10-K contains no mention of contamination beyond that narrow context, misleading employers into treating the test as universally reliable.Marijuana detection remains scientifically unreliable. The 2003 filing stated plainly that marijuana was “the most challenging” drug to detect and required “the most sensitive of equipment” for accurate measurement. By 2025, that disclosure is omitted, and cannabis is presented alongside other substances without distinction, despite ongoing concerns about passive exposure, environmental uptake, and the absence of well-validated THC metabolites in hair.

The method remains self-validated and scientifically contested. Psychemedics continues to cite customer adoption, FDA 510(k) clearance, and detection rates as proxies for validity. However, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the federal authority on workplace drug testing, has never endorsed the test. No national scientific body has published a peer-reviewed consensus declaring RIAH testing to be a reliable indicator of intentional drug use across substances and populations.

Ingestion ≠ Use. Psychemedics’ method detects ingestion, but it does not distinguish between active drug use and passive exposure. Yet public and private employers treat a positive result as dispositive, leading to discipline, termination, and reputational damage without corroboration or contextual evidence.

Legal Implications:

Public employers such as the NYPD may face exposure under:

Title VII (for racial disparate impact, particularly against Black employees with higher melanin concentrations in hair)

ADA (for penalizing lawful medication use or disability-related attendance issues)

Due Process Clause (for imposing penalties based on contested or scientifically unvetted evidence)

Fourth Amendment (if bodily samples are collected under coercive or constitutionally deficient procedures)

Private employers are similarly vulnerable under:

Title VII, ADA, and state/local anti-discrimination laws

Common-law tort claims, including defamation, wrongful discharge, and negligent reliance

Conclusion:

SAMHSA has never approved hair testing. Its contamination risks remain unresolved, its marijuana detection capabilities remain uncertain, and its foundational assumptions about exposure, use, and forensic reliability have not been subjected to rigorous scientific consensus.

Yet Psychemedics’ evolving 10-K filings tell investors and regulators only part of the truth—substituting selective validation for independent science, and generalizing narrow studies into sweeping forensic claims. Until national regulatory bodies formally endorse hair testing, and its scientific reliability is peer-reviewed across substances and populations, RIAH testing must be categorically barred from all employment decisions.

Public trust, civil rights, and institutional integrity depend on it.

I. Introduction: The Rising Cost of Pseudoscience in the Workplace

Across the United States, public and private employers are turning to hair drug testing technologies to enforce zero-tolerance workplace policies. These methods are marketed as modern, tamper-proof, and scientifically precise, offering a supposedly neutral tool to detect and deter employee drug use. Nowhere is this more consequential than in law enforcement, where institutions like the New York City Police Department (NYPD) use Radioimmunoassay of Hair (RIAH) testing—supplied by vendors like Psychemedics Corporation—to justify discipline, deny promotions, suspend employees without pay, or terminate officers outright.

However, the institutional reliance on RIAH is built on scientific misrepresentation and regulatory silence.

While marketed as “objective,” hair testing is a method with a well-documented history of contamination risks, racial and biological disparities, and a profound lack of scientific consensus. Although employers treat a positive result as near-incontrovertible evidence of drug use, the methodology used by Psychemedics and others has never been approved by the federal government for workplace testing, nor has it been endorsed by the scientific bodies employers claim to defer to.

Even more concerning, Psychemedics has publicly acknowledged many of these limitations in filings to the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). It’s 2003 and 2025 10-K reports, submitted under penalty of securities fraud, reveal a narrative of technical uncertainty that directly contradicts the sense of forensic certainty conveyed to employers. For instance, while Psychemedics told the SEC that marijuana was ‘the most challenging’ drug to detect in hair and that contamination remained a serious threat—even after the introduction of a proprietary wash protocol—there is no evidence that these critical limitations were ever conveyed to the NYPD or other law enforcement agencies, let alone meaningfully evaluated. Whether the information was withheld or ignored remains unclear. What is clear, however, is that the decisions being made based on RIAH test results rarely, if ever, reflect these unresolved risks.

Over time, the company’s public narrative has evolved from qualified caution to implied scientific finality, even as core problems remain unresolved. The result is that employees are losing their jobs, reputations, and careers based on a test method that, by the company’s admission, can not reliably distinguish passive exposure from intentional use or function without elaborate mitigation protocols that have not been validated across substances.

This article argues that the continued use of Psychemedics’ RIAH testing, particularly in the public sector and especially as a sole basis for adverse employment action, raises serious due process, civil rights, and scientific reliability concerns. Through a comprehensive examination of Psychemedics’ own SEC disclosures, federal agency positions, and the current state of toxicological science, this piece makes the case for an immediate moratorium on RIAH testing until and unless the methodology is independently validated, federally endorsed, and subjected to full civil rights review.

In a democratic society, the law demands that employment decisions—particularly those involving constitutional protections—be grounded in evidence, not assumption, and in science, not branding. Until those standards are met, hair testing will not be possible in American workplaces.

II. What Is RIAH Testing, and Why Do Employers Trust It?

Hair drug testing has long appealed to employers, especially in law enforcement, transportation, education, and other safety-sensitive sectors, for one simple reason: it promises certainty. In contrast to urine or oral fluid testing, which provide a narrow detection window and are susceptible to adulteration or sample substitution, Radioimmunoassay of Hair (RIAH) offers a powerful narrative: long-term drug use, rendered visible at the molecular level, immune to tampering.

That narrative is what Psychemedics Corporation, the industry’s dominant vendor, has successfully marketed for over three decades. The company’s patented RIAH methodology—based on proprietary radioimmunoassay protocols combined with confirmation by gas or liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry—purports to identify the presence of specific drugs or their metabolites trapped within the structure of the hair shaft. According to Psychemedics’ promotional materials, the test can detect drug use going back 90 days or longer, depending on the length of the hair sample.

How RIAH Differs From Other Testing Methods

Traditional urine testing is limited to detecting recent drug use, generally within 1–5 days of ingestion (or 1–2 days for most substances). Oral fluid testing has an even shorter window. RIAH, by contrast, claims to capture a longitudinal history of drug ingestion—effectively building a biochemical diary of use.

Employers often see three key benefits in RIAH testing:

Long detection window: Hair grows slowly (~1.3 cm/month), so a 3.9 cm sample theoretically reflects about 90 days of drug exposure.

Low tampering risk: Hair collection is observed and less invasive, reducing the risk of substitution or dilution.

Visual objectivity: The hair strand becomes evidence, promising more than a fluid test’s ephemeral result.

These advantages have made RIAH particularly attractive for:

Pre-employment screening is used to filter applicants.

Return-to-duty assessments, especially in civil service;

Post-incident investigations, where departments seek retrospective drug use patterns.

Promotional or reinstatement decisions, where supervisors seek to assess “fitness for service.”

But Beneath the Surface: Contamination, Bias, and Self-Validation

Despite this appeal, what employers are relying on is a scientifically disputed, vendor-controlled system that lacks meaningful regulatory oversight and suffers from multiple methodological flaws:

Contamination-prone: As Psychemedics itself acknowledged in its 2003 SEC filings, external drug exposure, via sweat, smoke, or surface contact, can bind to the hair. The company developed a proprietary wash protocol to reduce contamination. Still, even its cited studies (including a 2014 FBI study) apply only to cocaine, under idealized conditions, and have never been generalized to drugs like THC or methamphetamine.

Racially biased: Numerous studies have demonstrated that hair color, texture, and melanin concentration influence drug binding, making Black individuals disproportionately more likely to test positive than white individuals, even when drug exposure is identical. This has been confirmed by litigation and forensic analysis, yet most employers remain unaware of—or ignore—these findings.

Self-validated: Psychemedics’ testing methodology has not been approved by SAMHSA or the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and no independent scientific body has declared it a reliable measure of intentional drug use. Instead, the company relies on customer studies, comparative detection rates, and internal R&D to support its claims—validation by repetition, not regulation.

The Critical Disconnect: Perceived Objectivity vs. Actual Risk

Employers often mistake complexity for credibility. The scientific jargon surrounding RIAH—the mass spectrometry, the antibodies, the metabolite markers—creates an aura of precision. But beneath that, RIAH is a subjective system of probabilistic interpretation, conducted entirely by private labs. It has proprietary thresholds, lab-controlled sample preparation, and no meaningful right of rebuttal or appeal for the person tested.

Unlike blood alcohol content testing, where numeric thresholds are standardized, machines are calibrated, and court admissibility has been litigated for decades, there are no federal cutoffs for hair drug positivity. No regulatory body imposes uniform protocols on Psychemedics or its competitors.

In effect, the test becomes whatever the vendor says it is, and employers, including the NYPD, continue to accept those results as conclusive without demanding scientific or regulatory accountability.

III. Psychemedics’ SEC Filings Tell a Cautionary Tale

For over two decades, Psychemedics Corporation has assured investors that its patented RIAH testing is scientifically superior to traditional urinalysis. However, what it discloses to shareholders and what is emphasized to employers are markedly different. A careful comparison of its 2003 and 2025 Form 10-K reports—both filed under penalty of securities fraud—reveals a disquieting evolution: from candid acknowledgment of technical limitations to selective reassurance and omission.

This shift has profound implications. Public employers like the NYPD and private employers nationwide continue to rely on marketing-level narratives of forensic precision without understanding the unresolved scientific flaws Psychemedics has disclosed to investors. Each subsection below reveals a critical fault line.

A. Detection Delay: RIAH Is Scientifically Unfit for ‘For-Cause’ or Post-Incident Use

Hair grows at approximately 1.3 cm per month. Drugs are incorporated into hair only after they pass through the bloodstream, diffuse into the follicle, and become embedded in the keratin matrix. This takes time, meaning RIAH cannot detect drug use in the immediate aftermath of ingestion.

Psychemedics admits this in both its 2003 and 2025 filings:

“Because hair starts growing below the skin surface, drug ingestion evidence does not appear in hair above the scalp until five to seven days after use. Thus, hair testing is not suitable for determining impairment in ‘for cause’ testing such as is done in connection with an accident investigation.”

—2003 Form 10-K, p. 5; repeated verbatim in 2025 Form 10-K, p. 3

Yet employers routinely use RIAH test results in precisely those scenarios—accident reviews, workplace disruptions, and post-incident fitness assessments—despite the method’s acknowledged biological latency. From a legal standpoint, this constitutes a disconnect between scientific suitability and operational deployment, increasing the risk of wrongful adverse action.

B. Contamination: A Known Threat, Now Selectively Disclosed

In 2003, Psychemedics undertook a technical comparison of decontamination procedures:

“Additional research was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of a methanol wash in comparison to the Company’s wash procedure, (which entails an isopropanol wash followed by multiple extended buffer washes), in removing, and accounting for, external contaminants on the hair.”

—2003 Form 10-K, p. 9

The company acknowledged that short methanol washes were ineffective, and described its extended protocol as “a conservative policy” intended to reduce—but not eliminate—environmental contamination.

But by 2025, that caution was replaced with a selective reference to a single study:

“Our decontamination wash protocol and the effects in eliminating surface contamination were analyzed in a study conducted by scientists at the Laboratory of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI)… The FBI concluded that the use of an extended wash protocol of the type used by [Psychemedics] will exclude false positive results from environmental contact with cocaine.”

—2025 Form 10-K, p. 2

Critically:

The FBI study addressed only cocaine under controlled laboratory conditions.

It did not include marijuana, methamphetamine, opioids, or polysubstance exposure.

It has not been independently reproduced in peer-reviewed literature.

This shift from transparent disclosure of technical limitations to implied universal efficacy misleads investors and downstream users. There is no scientific consensus that any hair decontamination protocol—Psychemedics included—can fully distinguish external exposure from ingestion across all drug classes. And yet, employers are never informed of this limitation in real-world use.

C. Marijuana Detection: A Persistent Blind Spot

Psychemedics’ 2003 10-K included a revealing admission:

“Some additional research has been conducted in the measurement of concentrations of marijuana by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry/Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS/MS). This has been the most challenging, and requires the most sensitive of equipment for its accurate measurement and qualitative identification.”

—2003 Form 10-K, p. 9

That language is conspicuously absent in the 2025 10-K. Marijuana is now listed alongside other substances as if detection is routine:

“The Company provides testing and confirmation by mass spectrometry using industry-accepted practices for cocaine, marijuana, PCP, methamphetamine, and opiates.”

—2025 Form 10-K, p. 2

What’s unmentioned?

No validated THC-specific metabolite has been widely accepted as evidence of ingestion in hair.

THC is highly lipophilic, meaning it binds to hair externally with ease.

Passive exposure can easily lead to false positives, particularly in poorly ventilated environments.

Despite these issues, no cutoff levels for THC in hair have been standardized by SAMHSA, the World Health Organization (WHO), or any central forensic body. Employers, relying on RIAH results, are never told that a positive marijuana test may reflect secondhand smoke exposure or environmental contact, not active use.

D. Self-Validation ≠ Scientific Consensus

Throughout both filings, Psychemedics leans heavily on customer adoption, comparative positivity rates, and FDA 510(k) clearance to bolster its claims of test reliability:

“Some of the Company’s customers have also completed their own testing to validate the Company’s proprietary hair testing method… These studies have consistently confirmed the Company’s superior detection rate compared to urinalysis testing.”

—2003 Form 10-K, p. 3

“We believe that our patented process, superior wash procedure, and continued focus on scientific integrity distinguish us… Our hair tests are used by thousands of clients worldwide in safety-sensitive industries, education, and criminal justice.”

—2025 Form 10-K, p. 2

But what’s missing is more telling:

No mention of SAMHSA, which has repeatedly declined to authorize hair testing for federal programs.

No peer-reviewed, independent toxicology consensus endorsing RIAH testing across all major drug classes.

No uniform, federally mandated cutoff levels for interpretation of results.

In other words, Psychemedics relies on market adoption in place of scientific vetting. What courts expect—under Daubert or Frye—is independent expert consensus. What employers are being sold is vendor branding.

Conclusion: A Pattern of Overstatement, Not Oversight

What emerges from Psychemedics’ filings is a two-track narrative: technical caution and admission for investors, paired with scientific certainty and omission for institutional clients. This creates a dangerous evidentiary gap where employers make permanent, career-ending decisions based on data that the company itself has cautioned is inconclusive or subject to unresolved risk.

In legal terms, this mismatch between scientific transparency and forensic deployment is more than an administrative oversight—it’s a constitutional and civil rights liability.

IV. The SAMHSA Silence: A Red Flag That Can’t Be Ignored

Perhaps the most telling signal that RIAH testing is not ready for institutional reliance comes from the agency with the most explicit mandate to regulate drug testing in the workplace: the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Despite decades of lobbying and vendor-led pilot programs, SAMHSA has never approved hair testing for inclusion in its Mandatory Guidelines for Federal Workplace Drug Testing Programs.

This refusal is not an administrative delay but an ongoing rejection grounded in unresolved scientific, procedural, and civil rights concerns.

A. SAMHSA’s Mandate and Why It Matters

Under Executive Order 12564 and the Drug-Free Workplace Act of 1988, SAMHSA oversees the federal drug-free workplace testing program, which sets the gold standard for reliability, uniformity, and fairness. Its guidelines dictate:

Which testing methods are authorized (urine and oral fluid only, as of 2025),

What drugs are to be tested,

What cutoff levels apply,

What laboratory protocols and confirmatory requirements must be followed, and

What quality control and chain-of-custody safeguards are required.

Because of SAMHSA’s unique role, its silence on hair testing is an institutional warning. Agencies like the NYPD that rely on RIAH in disciplinary contexts are, in effect, deploying a method federal regulators refuse to endorse.

B. Why SAMHSA Has Rejected Hair Testing—Repeatedly

SAMHSA’s official explanation for declining to include hair testing has remained consistent over the last two decades. The concerns include:

1. Lack of Standardization Across Laboratories

Hair testing procedures are not uniform. Each vendor—Psychemedics, Omega, Quest, etc.—uses proprietary wash protocols, variable segmenting lengths, and laboratory-specific thresholds. Without national standards, two labs may interpret the same sample differently.

2. No Federally Accepted Cutoffs or Confirmation Metrics

Unlike urine and oral fluid testing, where immunoassay positives are confirmed via mass spectrometry with fixed cutoffs (e.g., 50 ng/mL for THC-COOH in urine), hair testing lacks universal numerical standards. Psychemedics sets its own, undisclosed thresholds.

This violates basic forensic principles of repeatability and transparency, creating due process concerns.

3. Racial and Biological Disparities

Hair structure, melanin content, and cosmetic treatment history affect drug incorporation. Black individuals and people with tightly coiled or highly pigmented hair are more likely to retain drug residues, even at identical levels of exposure. Courts and scientific journals have repeatedly acknowledged these disparities.

For example:

The National Institute of Justice has acknowledged the challenges associated with hair drug testing, including the potential for racial disparities. In a 2023 article, the NIJ noted that differences in hair growth rates and drug binding based on melanin content could lead to equity concerns in hair drug testing.

Jones v. City of Boston found that Black officers were disproportionately impacted by RIAH testing and that the city failed to justify its use under Title VII.

SAMHSA’s refusal to authorize hair testing reflects these systemic inequities—a risk public employers cannot ignore.

C. Implications for Employers: A Legal and Governance Breakdown

The absence of SAMHSA approval does not merely mean hair testing is inadmissible in federal jobs. No federal regulatory body has concluded that the method is scientifically or procedurally fit for workplace enforcement.

This exposes employers to cascading legal risk:

Procedural due process challenges under state and federal constitutions (for public employers),

Disparate impact claims under Title VII and analogous state laws (for both sectors),

Labor grievance exposure in unionized environments,

Negligent reliance and defamation claims, particularly where employers treat RIAH results as conclusive without corroborating evidence.

Moreover, the lack of SAMHSA approval becomes a key evidentiary issue in administrative proceedings and litigation. Courts may find that hair testing fails under Daubert or Frye standards, particularly where no federal agency recognizes the method’s forensic integrity.

Conclusion: Regulatory Silence Is a Policy Signal

SAMHSA’s continued exclusion of hair testing from the federal drug testing program sends a clear and deliberate message: RIAH is not ready for evidentiary or employment use in high-stakes settings. No amount of commercial adoption, branding, or internal validation changes was made. For public employers like the NYPD, continued reliance on RIAH is not only scientifically unwise—it is institutionally negligent.

Until this method is scientifically standardized, racially validated, and federally endorsed, it must be treated not as forensic evidence, but as what it is: a private-sector diagnostic tool lacking regulatory legitimacy.

V. Legal and Ethical Risks to the NYPD and Other Employers

The continued reliance on Psychemedics’ RIAH testing—particularly by public institutions like the NYPD—presents far more than a technical or policy concern. It creates a multi-front liability structure under federal civil rights law, state anti-discrimination statutes, constitutional due process doctrine, evidentiary admissibility standards, and collective bargaining agreements. Employers using RIAH are not just adopting a flawed scientific tool but exposing themselves to litigation and systemic risk across every dimension of public accountability.

A. Disparate Impact Liability Under Civil Rights Law

Numerous scientific studies and court records have established that RIAH testing disproportionately impacts Black individuals. Melanin-rich hair binds drug metabolites like cocaine and THC more readily. It retains them longer, making false positives or inflated results far more likely among Black employees than their white counterparts, even when usage is equivalent or absent.

This biological disparity creates direct liability under:

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

New York State Human Rights Law (NYSHRL)

New York City Human Rights Law (NYCHRL)

Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures, 29 C.F.R. § 1607.3(A)

Under Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971), any employment practice that disproportionately impacts a protected class must be justified by “business necessity” and shown to lack a less discriminatory alternative. Hair testing fails both prongs. No employer can credibly argue that RIAH testing is the only, or even the best, method of drug detection, especially when oral fluid testing provides comparable detection without the racial skew.

In Jones v. City of Boston, the district court found that Psychemedics’ hair test produced disparate racial impacts that the city failed to justify. Though the First Circuit later reversed on procedural grounds, the underlying scientific and statistical evidence of bias was never rebutted. Despite this evidentiary history, the NYPD, which relies on Psychemedics’ testing, risks replicating this liability.

In Ricci v. DeStefano, 557 U.S. 557 (2009), the Supreme Court held that employers must actively respond to evidence of disparate impact—but must do so carefully. Here, employers have been on notice for over a decade. Continued use of RIAH under these conditions could be framed as willful blindness.

B. Due Process and Procedural Fairness Violations

Public employees, particularly civil service personnel, are entitled to procedural due process under the Fourteenth Amendment. In Cleveland Bd. of Educ. v. Loudermill, 470 U.S. 532 (1985), the Supreme Court held that when a government employer seeks to deprive an employee of a property interest in continued employment, it must provide notice, a meaningful opportunity to respond, and a decision based on reasonably reliable evidence.

RIAH testing, as deployed by the NYPD and others, often fails this standard:

No opportunity to challenge the science behind the test.

No ability to cross-examine lab personnel.

No accommodation for rebuttal evidence (e.g., negative urine test).

No disclosure of thresholds, protocols, or wash effectiveness.

In some NYPD cases, officers have been suspended without pay, denied reinstatement, or subjected to retaliatory psychological evaluations based solely on RIAH results, even where urine, polygraph, or independent tests indicated no drug use. Such processes may violate not only Loudermill, but also the balancing test in Mathews v. Eldridge, 424 U.S. 319 (1976), requiring procedures commensurate with erroneous deprivation risk.

Suppose the NYPD uses unreliable science as final evidence to suspend or discipline its officers without adversarial review. In that case, it risks liability under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 for violations of constitutional rights under color of law.

C. Scientific Reliability and Evidentiary Admissibility

Even beyond civil rights and constitutional concerns, employers may face a fundamental evidentiary challenge: the science doesn’t meet the legal threshold for admissibility.

Under the Daubert standard (federal courts) and Frye standard (New York), expert evidence must meet a baseline of reliability. Key factors include:

General acceptance in the scientific community.

Peer review and publication.

Known error rates.

Existence of standards and controls.

RIAH testing fails these tests:

It is not endorsed by SAMHSA, the only federal agency empowered to approve workplace drug testing methods.

There are no published federal cutoffs or controls for interpreting hair test results.

The method is proprietary, meaning employers and courts cannot evaluate internal protocols.

External contamination, passive exposure, and cosmetic interference remain unresolved risks.

Courts applying Daubert or Frye could easily exclude RIAH evidence. Yet employers rely on it as dispositive. That contradiction exposes litigation, especially when employment actions are taken without corroboration or context.

D. Pattern, Practice, and Deliberate Indifference

The longer public employers continue to use RIAH despite mounting evidence of unreliability and racial disparity, the stronger the case for pattern and practice liability. For governmental entities like the NYPD, this may rise to:

Monell liability under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 for custom, policy, or practice violating constitutional rights.

Deliberate indifference to civil rights violations through continued reliance on contested tools.

Unfair labor practice claims where tests are used to circumvent due process in unionized settings.

For private employers, continued RIAH testing after complaints or internal findings may support punitive damages under the ADA, Title VII, or equivalent state laws.

This exposure is not abstract. It is systemic. As the scientific, regulatory, and evidentiary case against RIAH continues, employers clinging to the tool move from negligence to institutional recklessness.

E. Universal Procedural Harm: Fairness Erodes for All

While RIAH testing disproportionately impacts Black employees due to biological differences in hair structure and melanin concentration, its systemic flaws—unregulated thresholds, proprietary wash protocols, external contamination risks, and lack of scientific consensus—render it unfair and unreliable for all employees, regardless of race.

An employee with no history of drug use can be falsely accused based on environmental exposure (e.g., secondhand cannabis smoke in a shared residence).

Someone lawfully taking prescription medication can test positive for an opioid metabolite that doesn’t distinguish between illegal and medical use.

Officers or workers may be subjected to discipline, demotion, or psychological evaluation based on a result that cannot confirm when, how, or why a substance entered their body.

The use of RIAH testing removes context from discipline. It displaces judgment with opacity. Whether the employee is Black, white, disabled, or simply unlucky, the method disrupts due process and undermines the employer’s credibility. In doing so, it transforms flawed science into a universal procedural injustice.

Conclusion: Flawed Science, Systemic Liability, Universal Harm

Hair testing is not merely an unregulated tool—it is a flawed instrument of employment decision-making that places public and private employers in legal jeopardy. The risks extend across multiple dimensions:

Civil rights liability from racially disparate outcomes tied to melanin levels and hair structure;

Due process violations from disciplinary procedures that rely on opaque, contested evidence.

Evidentiary failure under Daubert and Frye standards that demand scientific reliability and general acceptance;

Institutional exposure under § 1983 and Monell for continuing to use a contested method after being put on notice.

Perhaps most dangerously, RIAH testing undermines fairness for all employees, regardless of race, gender, medical status, or role. It replaces individualized assessment with algorithmic suspicion. It treats contamination as guilt, passive exposure as intent, and vendor-defined thresholds as truth. It deprives workers of context, rebuttal, and voice.

Whether used to target, discipline, or deny promotion, the method is procedurally unsound and scientifically uncertain. And where the NYPD or any employer makes it the foundation for adverse action, they replace due process with probability and fairness with forensics by fiat.

The true liability is institutional: when flawed science becomes official policy, every employment decision it affects is risky.

Until RIAH testing is subject to meaningful scientific consensus, regulatory oversight, and civil rights scrutiny, its continued use isn’t just questionable—it’s unconscionable.

VI. Policy Recommendation: Preclude the Use of RIAH Testing Absent Scientific Consensus

The evidentiary and legal record is now clear: Radioimmunoassay of Hair (RIAH) testing is not fit for employment decision-making, especially in public agencies tasked with upholding constitutional rights, labor protections, and evidentiary standards.

In light of the known risks of contamination, unresolved racial disparities, scientific uncertainty, and the absence of regulatory approval from any federal agency, public employers like the NYPD must act decisively to halt RIAH testing until meaningful reforms are enacted.

A. Immediate Moratorium on RIAH Testing

All public employers—including the NYPD, FDNY, transit authorities, and municipal agencies—should issue an immediate administrative directive barring the use of RIAH testing in any employment decision involving:

Hiring or onboarding;

Probationary employment extensions or terminations;

Promotions, transfers, or reinstatements;

Investigations related to alleged drug use;

Disciplinary proceedings or psychological referrals;

Return-to-duty assessments after leave.

This moratorium must remain in place until scientific consensus is reached and regulatory endorsement is obtained.

B. Conditions for Reinstatement of Use

No agency should be permitted to resume use of RIAH testing unless the following criteria are met:

1. Regulatory Approval by SAMHSA or NIH

Hair testing must be approved and incorporated into the Mandatory Guidelines for Federal Workplace Drug Testing Programs by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), or recognized as valid by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), including:

Uniform federal cutoff thresholds,

Standardized lab protocols,

Cross-laboratory reproducibility benchmarks,

Validated racial and hair-type neutrality.

2. Peer-Reviewed Scientific Consensus

There must be published, independent validation of RIAH testing across drug classes in peer-reviewed forensic journals, including:

Confirmed ability to distinguish between ingestion and passive exposure;

Specificity and reliability for marijuana, opioids, and other contested substances;

Demonstrated wash protocols capable of removing contamination without degrading internal drug markers.

3. Civil Rights Audit and Public Disclosure

An independent civil rights audit must assess the racial, gender, and disability-based impacts of RIAH use over the past decade within any agency proposing to reinstate it. This includes:

Historical data on racial disparities in test outcomes;

Promotion, suspension, or termination decisions tied to hair testing;

Documentation of internal complaints or union grievances.

The results must be disclosed publicly to inform employees, unions, and policymakers of systemic risk exposure.

C. Broader Legislative and Policy Reform

To prevent future misuse of unvalidated forensic technologies, New York State and City legislatures should consider enacting:

1. The Public Employee Drug Testing Integrity Act

A law that would:

Ban any government agency from using drug testing methods not approved by SAMHSA or NIH;

Require notice, evidentiary disclosure, and right to rebut for any adverse action based on drug testing;

Prohibit exclusive reliance on proprietary forensic methodologies in employment decisions.

2. A Statewide Civil Rights Audit of Forensic Testing in Employment

Led by the New York State Division of Human Rights or an independent commission, this audit would:

Survey all public agencies using forensic drug tests (urine, oral fluid, hair, etc.);

Document disparate outcomes, especially for Black, brown, and disabled employees;

Evaluate procurement practices and the influence of vendor lobbying on testing adoption.

D. Transition to More Reliable, Validated Alternatives

In the interim, agencies should standardize the use of oral fluid or urine testing, which:

SAMHSA currently approves them for workplace testing.

Offer shorter detection windows but greater accuracy for recent use;

Can be combined with impairment assessments, prescription disclosure, and medical review officer (MRO) oversight.

While not flawless, these alternatives are subject to federal standards, evidentiary review, and biological clarity, while hair testing is not.

Conclusion: Policy Must Follow Evidence, Not Convenience

It is not enough for institutions to say they didn’t know. The SEC filings, court decisions, regulatory silence, and scientific literature make clear what the law now demands: an end to RIAH-based employment decisions until external, independent validation exists.

Until then, every agency that uses the Psychemedics’ test—or any similar tool—is not ensuring safety or fairness. It assumes risk, replicates bias, and violates the core principles of scientific integrity, employment justice, and public trust.

The time for caution is over. The time for prohibition is now.

VII. Conclusion: When Science Lags, Rights Are at Risk

Psychemedics’ RIAH testing presents itself as scientific, precise, and objective. But beneath that clinical veneer is a method fraught with uncertainty, distortion, and structural bias. What it detects is not always use—but sometimes exposure, physiology, or injustice. What it claims as truth is often a vendor-controlled interpretation, not consensus-backed evidence.

When employers—especially government agencies like the NYPD—base life-altering decisions on a test without federal regulatory approval, standardized cutoffs, or peer-reviewed consensus, they are not engaging in science. They are outsourcing judgment to pseudoscience.

The implications are profound:

Officers have been suspended or denied promotions based on test results that can’t distinguish ingestion from environmental contact.

Black employees face elevated risk due to nothing more than the natural structure of their hair.

Disabled workers and caregivers are written up for “time and attendance” issues after being denied fair hearings or contextual review.

Employers rely on evidence that wouldn’t survive courtroom scrutiny to make irrevocable employment decisions.

Science without regulation is not science—it is power disguised. And when that power is used to silence, punish, or remove employees—particularly whistleblowers, caregivers, or historically marginalized groups—the result is not workplace safety. It is institutional betrayal.

A Call to Action for Employers, Lawmakers, and Courts

This is not merely a civil rights issue. It is a test of democratic integrity. If due process, equal protection, and fair employment are to mean anything, then we must refuse to allow proprietary, race-disparate, contamination-prone tools to govern our public institutions.

Employers must halt the use of RIAH testing until validated by independent scientific bodies and approved by SAMHSA or NIH.

Legislatures must enact oversight frameworks that preclude using forensic methods without public standards.

Courts must rigorously apply Frye and Daubert and refuse to credit science that has not met the burden of proof.

Labor unions must defend their members from private tools masquerading as public interest.

The Bottom Line

No one should lose a job, be denied a promotion, or face a disciplinary charge because of science that has not been proven, reviewed, or regulated. Until the institutions charged with validation approve this method—until racial and scientific disparities are corrected—RIAH testing must be barred from any setting where liberty, livelihood, or dignity are on the line.

In science, uncertainty demands caution. In law, uncertainty demands due process. In a just society, both demand that we err on the side of rights, not risk.