Introduction

Civil rights settlements are supposed to resolve harm. In practice, they often conceal it—and enable it to repeat. When public institutions quietly pay millions to settle claims of harassment, discrimination, or retaliation, the public rarely hears about it. The harm is contained. The payout is buried. The governance failure, however, remains—unseen but persistent.

Each settlement may look like a legal conclusion. But taken together, they form a pattern of institutional dysfunction—where wrongdoing is acknowledged only in silence and compensated only in secrecy. These are not anomalies. They are part of how too many organizations manage liability: neutralizing whistleblowers, suppressing accountability, and avoiding meaningful reform. What’s disguised as resolution is often just reputational risk management.

This is not simply a matter of legal technicality or financial discretion. It is a more profound failure of governance. When governing bodies—boards of trustees, city councils, university administrations, internal legal departments—routinely sign off on settlement agreements without confronting the underlying culture that produced the harm, they are not managing risk. They are perpetuating it. And they are doing so at the expense of public trust, institutional integrity, and the civil rights the law was designed to protect.

This blog explores how civil rights settlements expose individual misconduct and systemic failures in oversight and leadership. It asks: What does it mean when public agencies and powerful institutions repeatedly pay for discrimination—and do so secretly? What happens when payouts become predictable line items and silence is institutionalized as a cost of doing business? And how should lawmakers, fiduciaries, watchdogs, and the public respond?

Because when the foundation cracks, it’s not just a legal issue. It’s a signal of misgovernance—and the longer it’s ignored, the deeper the damage becomes.

I. Settlements as Structural Red Flags

A civil rights settlement signals closure to most of the public—a legal wrong acknowledged, a check written, and a case resolved. However, inside the institutions that write those checks, something different often happens. There is no internal reckoning. No structural change. No meaningful consequence for those in power. The misconduct is framed as an isolated incident. The settlement is processed as routine. And the system that enabled the harm is left intact.

This is where misconduct becomes misgovernance.

A single settlement might reflect a bad actor or a one-time failure in oversight. But when payouts become recurrent, undisclosed, and quietly budgeted year after year, they reveal something more profound: an institution that treats civil rights violations as a cost of doing business, not a breach of public trust. The legal system may view each case on its own merits. But taken collectively, these settlements amount to an unofficial record of institutional dysfunction—a silent ledger of risk, retaliation, and leadership inaction.

This dynamic is more dangerous because the very people responsible for institutional accountability—senior administrators, general counsel, trustees, city managers, or school boards—are often the same actors who manage litigation behind closed doors. Settlements are negotiated without public input. No board resolution is required. No independent oversight is triggered. In many cases, even the governing body is kept at a distance from the facts, with key decisions delegated to risk managers and attorneys focused on reputational containment—not cultural repair.

And because there is no legal requirement to disclose these payouts in public-facing reports, the cycle continues. A university can settle multiple Title IX complaints over a decade without structural reforms. A police department can pay out repeated judgments for race and gender discrimination while insisting the problem is “personnel-specific.” A city agency can be sued repeatedly for retaliation, with no consequences for leadership—because the misconduct record lives in the shadows of settlement agreements and legal privilege.

This is not accidental. It is a feature of modern institutional risk management. The incentive is clear: contain the story, protect the brand, neutralize the threat. Every effort is made to treat each complaint as discrete, severed from past behavior or future consequence. This pattern-blindness is not just a failure of memory—it’s a deliberate legal strategy. It allows deeply entrenched cultures of discrimination to persist without scrutiny.

But while settlements may bury the facts, they cannot erase the truth. Every check written is a public signal—if not of legal guilt, then of organizational failure. And when those checks are signed in secret, paid with public money, and shielded from democratic oversight, they don’t just represent a legal cost. They represent a governance crisis.

Because what an institution hides, it doesn’t fix. And what it quietly pays for, it quietly repeats.

II. The Institutional Incentive to Stay Silent

If civil rights settlements signal misgovernance, institutional silence sustains it. The question isn’t just why discrimination, harassment, or retaliation occur—it’s why they persist. The answer lies in the incentives.

For institutions with reputational capital to protect—universities, police departments, public agencies, and multinational corporations—the appearance of accountability often matters more than accountability itself. Acknowledging systemic wrongdoing can jeopardize funding streams, spark regulatory scrutiny, or damage leadership credibility. The path of least resistance is quiet resolution: no admission of fault, minimal public exposure, and airtight confidentiality provisions.

Legal departments aren’t tasked with reforming culture but with containing exposure. Risk managers don’t ask whether a payout reflects institutional failure—they ask whether the harm can be neutralized. Executive leaders frame settlements as business decisions. Governing boards, city councils, and trustees often approve them as routine fiscal matters, reviewing liability and insurance coverage but rarely interrogating the cultural or operational failures that produced the harm.

This risk-averse logic produces a widespread culture of institutional defensiveness, where silence becomes policy and settlements become strategy. Agreements are shielded behind nondisclosure clauses. Complainants must forfeit their right to speak. No audit follows. No policy is reviewed. Just a check, a closure, and the internal message: risk managed.

This isn’t simply a moral failure. It’s a structural one.

Consider a public university system that quietly settled multiple gender discrimination and harassment lawsuits over a decade—each involving different departments, faculty, and female postdoctoral researchers. None were publicly acknowledged. No policies changed. No supervisors were disciplined. To outsiders, each payout looked isolated. But inside the institution, it was a pattern—a recurring cost that no one was willing to name.

This is how institutions normalize silence: by fragmenting the truth into separate legal events, treating every settlement as a one-off and every victim as expendable. In doing so, they avoid confronting what the evidence reveals: not episodic misconduct, but systemic neglect.

The legal framework is complicit in this cycle. While laws like the Freedom of Information Law (FOIL), Sunshine Laws, and Open Meetings Laws are designed to ensure public access to records—especially when public dollars are spent—these safeguards are routinely undermined. Agencies invoke exemptions, redact critical information, or delay responses until scrutiny fades. Non-disparagement clauses, no-fault language, and sealed agreements bury the facts under the guise of neutrality. Courts too often rubber-stamp these arrangements without weighing their impact on public accountability.

While these practices may violate the spirit—and at times, the letter—of open government laws, enforcement is rare. Instead, the legal tools intended to preserve transparency are weaponized to protect institutional reputation. What should be public accountability becomes organizational self-preservation, allowing repeat misconduct to continue behind a firewall of procedural legitimacy.

This silence also undermines institutional leadership’s fiduciary and ethical responsibilities—including those of both executive management and oversight bodies. Leaders must ensure the integrity of the institutions they serve by managing liability and preventing systemic harm. That responsibility cannot be fulfilled when civil rights violations are ignored or settlements are treated as routine operational costs. Yet in many cases, leadership is either kept in the dark—or complicit in keeping others there.

The more profound danger is that once concealment becomes standard, retaliation becomes cheaper than reform. Public trust becomes expendable in the service of litigation strategy. Silence becomes a shield. The institutional instinct is not to correct what caused the harm but to erase evidence if it ever occurred.

The consequences are not just legal or reputational. They are systemic. An institution that protects itself by suppressing harm does not serve the public. It serves itself.

III. When Leadership Fails: How Executives and Boards Protect Institutions, Not People

Civil rights settlements don’t appear out of nowhere. They result from decisions—often made at the highest levels of institutional power—about how to respond to harm. Whether it’s a CEO, general counsel, university president, agency commissioner, police chief, mayor, or city council, those in charge have the authority to resolve complaints and confront the systems that allowed the misconduct to occur. Too often, they choose silence over accountability—protection of the institution over justice for the people it is meant to serve.

This failure of leadership is not always overt. It hides behind neutrality, legal formality, and risk analysis. Civil rights violations are reframed as HR disputes. Retaliation is rebranded as performance issues. Settlement negotiations take place under the cover of legal privilege and confidentiality clauses. In government, these processes are often presented as “routine expenditures.” In corporate and academic settings, they’re labeled “employment matters.” The objective function is the same in every case: manage the fallout, not fix the cause.

What results is a model of governance in which leadership becomes the firewall, not the fix. Instead of serving as the first line of accountability, senior executives and public officials often become the last line of defense for reputations, funding streams, and political capital. The people harmed—employees, students, whistleblowers, or community members—can navigate both the original misconduct and the sobering realization that the institution’s leadership is aligned against them.

These aren’t isolated ethical lapses. They are systemic failures of duty. In public institutions, taxpayer dollars are deployed not to repair harm but to bury it. In private and nonprofit organizations, investor and stakeholder trust is quietly traded away for risk containment. And in both spheres, those with the most power to prevent abuse often become its silent enablers.

Structural design deepens the problem. Many public boards, like school boards, police commissions, or university trustees, operate with limited insight into day-to-day operations. City councils may approve settlements without ever reviewing the underlying facts. Executives—whether corporate, municipal, or academic—control the narrative, the flow of information, and the framing of legal exposure. Trustees and oversight bodies are presented with summaries, not substance. Even when presented with evidence of recurring violations, they often rationalize inaction as fiscal responsibility or legal caution. However, shielding institutions from scrutiny is not governance. It is complicity.

The consequences are profound. Leaders who ignore patterns of harm become architects of impunity. Oversight bodies that approve settlements without demanding change signal that institutional reputation outweighs public rights. Government agencies that treat civil rights violations as budgetary nuisances weaken public trust and democratic legitimacy. Institutions that prioritize discretion over disclosure are not correcting injustice—they are budgeting for it.

Ultimately, the issue isn’t just what these leaders fail to do. It’s what they actively choose to preserve: power without accountability, policies without enforcement, and justice without transparency.

If civil rights settlements are the smoke, failed leadership is the flame. And no amount of silence will extinguish what continues to burn beneath.

IV. Why Civil Rights Disclosure Is a Governance Issue—Not Just a Legal One

For decades, civil rights compliance has been siloed as a legal function. Policies are drafted to check regulatory boxes. Investigations are conducted to manage liability. Settlements are negotiated not to drive change but to avoid litigation. However, this legalistic framing misses a fundamental truth: Civil rights enforcement is not just a legal obligation but a governance responsibility.

When leadership—whether in a corporate boardroom, a university president’s office, or a government agency—treats these issues solely as legal risks to manage, it forfeits the opportunity and obligation to lead with integrity.

Disclosure is where that failure becomes most visible. When public or publicly accountable entities use taxpayer dollars, tuition revenue, endowment funds, or shareholder capital to settle claims of discrimination, harassment, or retaliation, those settlements should be subject to oversight. Yet most are hidden behind confidentiality clauses, redacted payment records, sealed court files, or attorney-client privilege. There is no dashboard, no pattern recognition, and no obligation to disclose whether the same actors reappear, whether retaliation followed, or whether reforms were ever implemented.

This opacity is not an accident. It is a governance choice, and it communicates clearly: the institution’s image matters more than its people’s civil rights.

In government, this silence undermines public trust. It distorts accountability to investors, donors, and stakeholders in private and nonprofit sectors. Across all industries, it emboldens repeat misconduct by shielding leadership from consequences. The law may permit confidentiality, but public-serving institutions should not demand it. The refusal to disclose repeat settlements, leadership inaction, or structural complicity is not a legal defense. It’s a values statement. And it prioritizes legal optics over structural reform.

Transparency is not a burden. It is a governance imperative. Any institution—public or private—that routinely resolves civil rights complaints must be able to answer a fundamental question:

What are we doing to ensure this doesn’t happen again?

Without disclosure, that question is never asked. Patterns remain invisible. Repeat offenders are protected. Institutional reforms are performative at best. And those with the most power remain shielded, while those with the least remain at risk.

To treat civil rights settlements as isolated legal events is to ignore what they truly represent: structural red flags. They are governance signals—indicators of what an institution tolerates, conceals, and refuses to confront. That makes disclosure not just a legal best practice but a fiduciary duty, a public obligation, and a test of institutional legitimacy.

If leadership cannot account for who it protects, who it harms, and who pays the price for silence, it has already failed its most basic duty: to govern in the public interest.

V. Proposing a Civil Rights Disclosure Framework—What Accountability Looks Like

Transparency is not just about information. It’s about power. In civil rights enforcement, disclosure functions as a democratic check on institutional actors—executives, public officials, trustees, and general counsel—who too often resolve misconduct in silence. It allows patterns to be seen, repeat actors to be identified, and demand for reform. Without it, even the most egregious forms of discrimination, harassment, or retaliation can be rendered invisible—buried beneath settlement agreements, legal privilege, and bureaucratic discretion.

To address this systemic failure, institutions must be required to publish standardized civil rights settlement data routinely, publicly, and uniformly—not selectively, not occasionally, and not only when media pressure forces disclosure. A modern disclosure framework would treat civil rights settlements like we treat material financial liabilities: reportable events subject to oversight, auditing, and reform.

This framework should include:

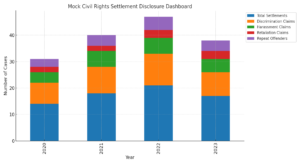

Annual public reporting of civil rights settlements’ number, nature, and total value, disaggregated by category (e.g., discrimination, harassment, retaliation) and by department or unit.

Disclosure of repeat violations involving the same leadership, divisions, or systemic conditions—even if individual actors have left or were reassigned.

Outcomes tracking, including whether settlements led to corrective actions, leadership changes, disciplinary measures, or internal policy reforms.

Whistleblower protections for individuals who disclose internal patterns of retaliation, suppression of reports, or manipulation of investigative outcomes.

Independent auditing authority to ensure the completeness, accuracy, and integrity of disclosures—including a mandate to identify when non-monetary settlements are used to obscure liability.

At the federal level, the Department of Justice, Department of Education, or EEOC could implement a “Component 2: Civil Rights Liability Disclosure”—modeled after the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s demographic reporting. Any institution receiving public funds, engaging in regulated commerce, or holding a public charter would be required to file annual civil rights settlement data with a centralized public database.

State legislatures could pass parallel legislation requiring public universities, school districts, law enforcement agencies, and local government departments to disclose civil rights settlements as a budget appropriation or grant eligibility condition. Municipalities could tie insurance coverage or indemnification to disclosure compliance, creating fiscal incentives for reform.

This is not merely policy. It is governance infrastructure—a structural mechanism to enforce institutional integrity and deter repeat harm. Civil rights settlements are not “legal housekeeping.” They are public indicators of leadership failure, cultural dysfunction, and oversight breakdown. The only way to fix what institutions conceal is to force it into public view.

Without disclosure, there is no accountability. Without accountability, there is no deterrence. And without deterrence, there is no justice—only repetition.

VI. The Financial and Ethical Cost of Secrecy

Secrecy doesn’t just obscure injustice. It enables it and makes the public pay for it. Every time an institution quietly settles a civil rights complaint, the money comes from somewhere: public budgets, insurance pools, tuition revenue, endowments, or shareholder returns. Yet rarely do the people funding those payouts—taxpayers, students, donors, or investors—know what they’re paying for, who is responsible, or whether anything has changed.

This isn’t just a problem of transparency. It’s a failure of governance and fiscal integrity.

When public agencies spend millions to settle discrimination or retaliation claims without disclosure or reform, they violate the trust that underpins democratic service. These are not discretionary expenses. They are liabilities incurred through harm. And when they go unexamined, they teach the wrong lesson: that misconduct is tolerable—as long as it’s affordable.

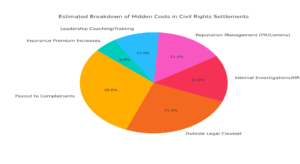

The financial impact is cumulative, obscured, and largely invisible. Settlements are often routed through risk funds, insurance policies, or legal budgets without public breakdown. Institutions may spend more on outside counsel, reputation management, or executive crisis response than restitution or structural change. This distortion of priorities reflects a culture in which protecting the brand outweighs protecting people.

But the cost is more than monetary. It’s institutional legitimacy.

A university that quietly settles sexual harassment claims but retains the faculty involved corrodes its academic mission. A police department that pays for repeated civil rights violations while denying wrongdoing loses moral authority. A corporation that conceals retaliation through legal privilege undermines investor trust and workforce stability. In each case, the institution survives—but its credibility dissolves.

For survivors and whistleblowers, secrecy compounds the harm. It sends a clear message: your experience is too inconvenient to confront, your truth too dangerous to acknowledge. Worse, it signals to perpetrators that silence can be bought, and power will shield them.

This isn’t responsible stewardship. It’s institutional gaslighting, and it undermines not only justice but also the very purpose of leadership—public or private.

Civil rights violations should never be normalized as operational costs. They are signals of governance failure. And the longer those failures are concealed, the more they become entrenched features of the systems we’re told to trust.

VII. Public Trust, Risk, and the Role of Lawmakers

Civil rights settlements are not just legal outcomes. They are public indicators of how institutions function, how power is exercised, and what leadership is willing to conceal. When handled in secret, they don’t just erode trust in the institutions that committed the harm—they erode faith in the systems that were supposed to prevent it.

Lawmakers can no longer afford to treat these disclosures as optional. The obligation to report and track civil rights settlements is not merely about compliance but also protecting civil rights, safeguarding public funds, and ensuring democratic accountability.

The harm of nondisclosure is not theoretical. It impacts real people: employees silenced after retaliation, students pushed out after discrimination, community members mistreated by agencies that never change. And yet, across jurisdictions, there is still no systemic tracking, mandatory reporting, or centralized oversight body monitoring these liabilities.

That absence creates measurable public risk. Cities and states spend millions on misconduct settlements—policing, education, public health, and housing—without disclosing the causes, actors, or changes implemented. These costs are invisible to taxpayers, bondholders, budget directors, and voters. The lack of civil rights transparency in the private sector obscures investor risk, undermines governance, and exposes employees to repeat harm.

This is not just a failure of leadership. It is a failure of law.

Lawmakers at every level—federal, state, and local—must act to modernize civil rights oversight by mandating transparency as a condition of public funding, regulated operation, or tax-exempt status. That means:

Enacting legislation that requires the publication of civil rights settlement totals, categories, and outcomes;

Tying public funding to full disclosure compliance for schools, universities, police departments, and state agencies;

Creating centralized civil rights liability registries, accessible to the public, press, and oversight entities;

Closing legal loopholes—such as overbroad confidentiality agreements or election of remedies rules—that obstruct accountability;

And protect complainants and whistleblowers from retaliation during and after the reporting process.

Good governance is incompatible with institutional secrecy. When public or public-serving entities hide civil rights violations, democracy suffers. Transparency is not a burden but a constitutional obligation and civic imperative. When institutions cannot or will not police themselves, it is the responsibility of the law to hold them accountable.

VIII. Conclusion — From Concealment to Accountability

Civil rights settlements tell a deeper story—not just about individual harm but institutional complicity, who has power, who is protected, and who is silenced. Every redacted record is a page torn from the public ledger. Every unacknowledged payout is a missed opportunity for reform. Every shielded perpetrator is a signal that impunity still governs behind closed doors.

This is not simply about disclosure. It is about dismantling the machinery of concealment—where legal compliance replaces moral clarity, and silence becomes strategy.

If civil rights law is to be more than symbolic, it must be enforced through legal action and structural transparency. That work does not rest solely with HR departments or compliance officers. Trustees, agency heads, board members, corporate executives, and elected officials belong to it. It is not just legal but civic, fiduciary, and democratic.

Accountability cannot begin in silence. And justice cannot end in a settlement.

The path forward begins by making these patterns visible—by naming the failure not as an administrative oversight but as a governance crisis. Because the institutions that fear sunlight the most are often the ones that need it the most.

A civil rights disclosure framework is not a procedural fix. It is a declaration that equity matters, that harm has a cost, and that public trust must be earned—not bought, buried, or sealed away.

This is how we move from concealment to accountability, not as a temporary correction but as a permanent condition of public power.