Executive Summary

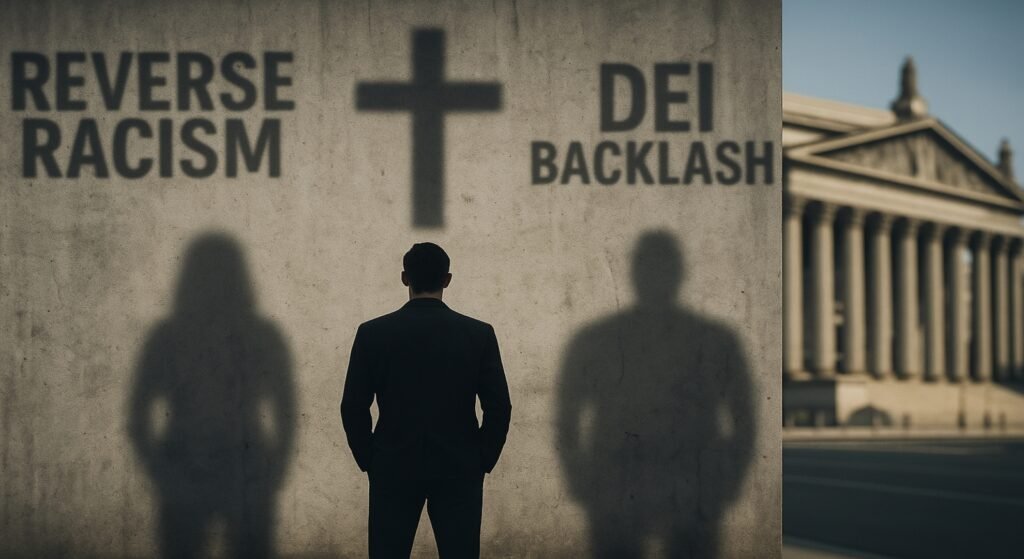

American public discourse is drowning in phantom grievances. We are told, insistently and with significant volume, that “reverse racism” is a threat to democracy, that Christians are being systematically persecuted in a majority-Christian nation, and that diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs are nothing more than Trojan horses for oppression. These narratives dominate headlines, inspire legislation, and shape litigation strategy. However, they are a distraction—a set of carefully constructed illusions that divert public attention away from the real crisis of American life: the rigid and intensifying social stratification.

This great distraction is not benign. It corrodes civil-rights law, distorts agency enforcement priorities, and emboldens courts to act as gatekeepers rather than guarantors of constitutional rights. Manufactured outrage retools the language of civil rights into weapons for dominant groups. At the same time, those who live with the daily burdens of systemic inequality—economic immobility, educational exclusion, housing instability, and workplace exploitation—are sidelined.

The judiciary itself has become complicit. At the district-court level, meritorious discrimination cases are routinely short-circuited at summary judgment, with judges substituting their own skepticism for the Seventh Amendment’s guarantee that juries, not courts, are the ultimate fact-finders. The Second Circuit has had to intervene repeatedly. In Knox v. CRC Management Co., LLC, the court reversed a district judge who dismissed a Black woman’s sworn testimony as “self-serving,” reinstating her claims of racial harassment, retaliation, disability discrimination, and wage theft. In Chislett v. New York City Department of Education, the court restored claims dismissed as “stray remarks,” holding that when leadership condones racially hostile trainings, that tolerance is itself actionable under Monell.

Both decisions reveal the same structural failure: trial courts using procedural tools to silence plaintiffs before juries ever hear them. This judicial gatekeeping, framed as prudence, is in fact bias—an erosion of civil-rights enforcement at the very stage where plaintiffs should gain access to trial.

Meanwhile, institutions exploit distraction. The NYPD’s Candidate Assessment Division weaponizes “psychological unfitness” labels to eliminate applicants, while its Aviation Division mishaps are buried in bureaucratic silence. When those stories leak, they are spun into hit pieces about “reverse discrimination” or “DEI gone wrong,” obscuring the institutional misconduct that actually drives inequality.

The cost is threefold:

Dilution of civil-rights law – turning statutes meant to dismantle structural inequities into venues for litigating every perceived slight.

Diversion of resources – forcing agencies like the EEOC to chase phantom claims at the expense of addressing entrenched inequities in housing, policing, and employment.

Erosion of trust – reducing public confidence in the legal system as every group claims victimhood while true systemic harms languish.

This commentary argues that phantom grievances, DEI myths, and judicial gatekeeping form a single ecosystem of distraction. They preserve hierarchy by turning our attention to shadows while the machinery of stratification continues to grind beneath our feet. The path forward is clear: stop fighting over who claims victimhood loudest, and confront the actual structures that decide whose children receive opportunity, whose voices are heard, and whose cases reach a jury.

I. Manufactured Outrage: False Narratives of Oppression

The genius of distraction politics is its simplicity: take the language of justice, hollow it out, and repurpose it to defend the status quo. Today’s cultural and legal debates are littered with such maneuvers—phantom grievances that cloak majority privilege in the garments of victimhood.

A. “Reverse Racism”

No phrase better illustrates this phenomenon than “reverse racism.” On its face, the term implies a symmetry: if racism means animus toward Black people, then the same animus toward whites must be “reverse.” But the symmetry is false.

Racism, properly understood, is not a matter of isolated insults or interpersonal hostility. It is a system—historically entrenched, institutionally enforced, and legally sustained—that privileges one group while subordinating another. In the United States, racism has operated for centuries to preserve white dominance through law (slavery, Jim Crow, redlining), economics (exclusion from GI Bill benefits, unequal wages), and culture (the presumption of whiteness as the societal norm).

Can white individuals experience prejudice or hostility in individual interactions? Of course. But prejudice is not equivalent to racism. When a white manager is passed over for a promotion, that may feel unfair; it may even involve bias. But it is not a mirror image of the structural obstacles that for generations excluded Black, Latino, or Asian workers from entire professions, neighborhoods, and schools. To call it “reverse racism” is not simply a category error—it is a deliberate tactic to erase the asymmetry of power and history.

Courts have wrestled with this distinction. Title VII of the Civil Rights Act is formally colorblind; it prohibits discrimination “because of” race against all individuals. But the law’s purpose, as Congress articulated in 1964, was remedial: to dismantle entrenched patterns of exclusion. When judges allow the language of Title VII to be weaponized against remedial policies like affirmative action or targeted recruitment, they convert the statute into something its drafters never intended—a shield for the already advantaged.

B. Christian “Persecution”

The same logic fuels claims of systemic Christian persecution. In a nation where over 60% of adults identify as Christian, where the federal calendar recognizes Christmas and Easter, and where Christian norms are baked into constitutional debates on abortion, marriage, and morality, the assertion of systemic oppression strains credulity.

Yes, individual Christians can and do face conflict in workplaces or schools—often around scheduling accommodations, dress codes, or personal expression. But those challenges pale in comparison to the structural hurdles faced by religious minorities: Muslims repeatedly targeted in surveillance programs and security screenings, Jews navigating antisemitic hostility in schools and workplaces, Sikhs forced to litigate for the right to wear turbans or beards in military service.

To claim systemic Christian oppression in the United States is to invert reality. It is to mistake the occasional friction of majority dominance for the daily marginalization of minority existence. Yet this inversion has become politically potent. Legislators invoke it to carve exemptions from civil-rights laws, allowing employers and public officials to deny services under the banner of “religious freedom.” Once again, the language of civil rights is repurposed to reinforce, not dismantle, stratification.

C. The DEI Backlash

The newest phantom grievance is the DEI backlash. In corporate boardrooms, universities, and government agencies, diversity, equity, and inclusion programs are caricatured as instruments of “reverse discrimination.” Critics insist they dilute meritocracy, inject politics into the workplace, and even violate Title VII by privileging candidates of color.

This argument collapses under scrutiny. DEI initiatives emerged in response to well-documented exclusion—decades of homogeneous hiring, glass ceilings, and systemic underrepresentation. They are not quotas (which are illegal), nor do they authorize hiring unqualified candidates. Instead, they seek to level the playing field by expanding access, addressing bias, and ensuring that historically marginalized groups are not excluded by inertia or design.

To brand every DEI initiative as oppressive is to strip equity of meaning altogether. Worse, it allows civil-rights law to be wielded against itself. Title VII was enacted to combat structural barriers; repurposing it to attack remedial equity programs is the very definition of legal jujitsu—turning the statute on its head to entrench the inequalities it was designed to dismantle.

The irony is almost too rich. Those who rail against DEI as a threat to fairness are not, in practice, defending neutrality. They are defending the comfort of stratification. The outrage is not about standards being lowered; it is about barriers being questioned.

D. Outrage as a Weapon

The common thread across these phantom grievances is strategic appropriation. By borrowing the rhetoric of discrimination, majority groups position themselves as the “new oppressed,” obscuring their own structural dominance. This has two effects:

It silences legitimate claims by reframing equity efforts as attacks, forcing marginalized groups to defend even the most modest remedial steps.

It distorts the legal system by flooding courts and agencies with claims that mimic the form of civil-rights complaints while hollowing out their substance.

The effect is cumulative: real inequality is obscured, resources are misdirected, and the judiciary is emboldened to act as a gatekeeper, dismissing claims wholesale on the assumption that “everyone discriminates,” so no discrimination is actionable.

II. The Real Dynamic: Social Stratification

While phantom grievances dominate headlines, the true architecture of inequality remains largely unexamined. The American project is increasingly defined not by isolated slights or cultural skirmishes, but by a rigid and intensifying structure of social stratification—the sorting of human beings into durable hierarchies of wealth, power, education, geography, and opportunity.

A. Class as the Hidden Organizing Force

At its core, stratification is economic. Whether a child is born into a household that can afford tutors, extracurriculars, and college consultants remains one of the strongest predictors of life outcomes. Wage stagnation has hollowed out the middle class, while consolidation at the top ensures that opportunity pools upward. DEI battles in the workplace, no matter how loudly litigated, do little to alter the fundamental fact that wealth increasingly dictates mobility.

B. Geography as Destiny

Stratification is geographic. Zip codes remain shorthand for opportunity. Children born in affluent suburbs are more likely to attend well-funded schools, live in safer neighborhoods, and access healthier food and healthcare. By contrast, urban districts and rural counties often see crumbling infrastructure, underfunded schools, and public institutions that serve more as surveillance mechanisms than ladders of opportunity. Race intersects with geography, but the overarching reality is that spatial inequity cements class inequity.

C. Education as the Gatekeeper

Education is the hinge of stratification. College degrees—especially from selective institutions—function as passports to stability. Yet rising costs and gatekeeping practices keep those passports out of reach for many. Standardized testing, legacy admissions, and credential inflation are less about measuring merit and more about reproducing privilege. When critics rail against affirmative action or DEI admissions, what they are defending is the exclusivity of an educational ladder that was never neutral to begin with.

D. Institutional Gatekeeping: The Candidate Assessment Division

Nowhere is stratification more visible than in the operation of public institutions tasked with policing access to public employment. The NYPD’s Candidate Assessment Division is a case study. Officially, it evaluates psychological fitness and background suitability for law enforcement service. In practice, it has weaponized vague standards to exclude candidates under the guise of “unfitness.”

Applicants are placed on so-called “psychological hold” not for mental health issues, but because they lacked paperwork—college transcripts, driving records—that investigators wanted off their desks. Rather than admit administrative delay, cases were rerouted into the psychological system, stigmatizing candidates with labels that followed them into future job searches. These practices did not merely inconvenience applicants; they reinforced stratification by disproportionately harming candidates from less privileged backgrounds—those without immediate access to documentation, those without networks to intervene, those who could least afford delay.

When media outlets run “hit pieces” painting rejected candidates as unstable or unqualified, they amplify the illusion of fairness: the system is simply “weeding out the unfit.” In truth, it is preserving the hierarchy of who gets to police and who gets policed.

E. Bureaucratic Evasion: The Aviation Division

The Aviation Division controversies tell a similar story. Ostensibly about safety and readiness, internal audits have exposed misuse of resources, lack of oversight, and politically convenient scapegoating. When whistleblowers emerge, the institutional instinct is not to reform but to punish—reassigning, smearing, or discrediting those who disrupt the narrative. The result is not greater accountability but deeper entrenchment.

Just as with Candidate Assessment, Aviation controversies reveal how institutions manage perception rather than address structural failure. Reports are buried, accountability is diffused, and public relations campaigns are deployed to reassure the public. Meanwhile, the actual machinery of stratification—who controls resources, who receives opportunities, and who is silenced—remains intact.

F. Media’s Complicity: Hit Pieces as Narrative Armor

The media plays its role in reinforcing stratification. Conveniently timed leaks and “exposés” about supposed reverse discrimination or DEI excesses serve as narrative armor for institutions under scrutiny. They redirect outrage toward individual plaintiffs or whistleblowers, framing them as opportunists or agitators, while deflecting attention from the underlying structural abuses.

When a rejected candidate is profiled as “too fragile” for police service, or when a training program is defended by ridiculing plaintiffs as oversensitive, the public debate shifts. The issue is no longer institutional misconduct but whether the individual is credible. This tactic not only neutralizes dissent but also legitimizes the gatekeeping apparatus.

G. Stratification as the Real Crisis

This is the real crisis—not phantom claims of “reverse racism” or the supposed fragility of the Christian majority. The real divide is structural. It is the architecture of stratification that ensures some candidates will always be held back, some workers will always be disposable, and some communities will always be surveilled instead of supported.

The danger is not just material. By focusing on phantom grievances, we lose sight of the fact that our legal and institutional systems are not neutral. They are active participants in reproducing inequality. Stratification is not accidental; it is designed, maintained, and defended—through bureaucratic maneuvers like psychological holds, through selective enforcement in Aviation scandals, through media hit pieces that shift blame onto the marginalized.

III. The Courts as Complicit Gatekeepers

If phantom grievances are the smoke and stratification is the fire, the judiciary has too often served as the ventilation system—circulating mistrust, filtering which cases survive, and suffocating those that challenge entrenched power. Civil rights statutes may promise redress, but those promises are routinely undermined by judicial gatekeeping, where judges substitute their skepticism for the factfinding role of juries.

A. The Seventh Amendment in Retreat

The Seventh Amendment guarantees the right to trial by jury in civil cases. It is not a technicality; it is the constitutional recognition that disputes about credibility, motive, and pretext must be resolved by ordinary citizens, not cloistered judges. Yet in practice, district courts wield Rule 12(b)(6) and Rule 56 as blunt instruments, dismissing discrimination cases before juries ever hear them.

The logic is circular: plaintiffs are told they need “smoking-gun” evidence of discriminatory policy, but discovery is denied because the evidence isn’t already in hand. Plaintiffs are told their testimony is too “self-serving,” as if lived experience is not evidence. Courts weigh credibility on paper, declaring some witnesses believable and others not, without the benefit of cross-examination or the constitutional safeguard of a jury.

This is not neutrality. It is judicial bias masquerading as prudence. And it is corrosive to the very idea of civil rights enforcement.

B. Knox v. CRC Management: “Credibility Is for the Jury”

The Second Circuit’s 2025 decision in Knox v. CRC Management Co., LLC is a case study in appellate correction. Natasha Knox, a Black woman of Jamaican descent working in Bronx laundromats, endured daily racial harassment, denial of disability accommodation, and wage theft. When she was terminated under dubious circumstances, she sued under § 1981, Title VII, the NYSHRL, the NYCHRL, the FLSA, and the NYLL.

The district court dismissed everything on summary judgment. Why? Because it deemed Knox’s sworn testimony “self-serving,” credited the employer’s account of events, and concluded that the evidence of racial hostility was not “severe or pervasive” enough to matter. Even her retaliation claim—fired weeks after complaining—was brushed aside.

The Second Circuit vacated in full. It reminded the district court that credibility is for the jury, not the judge. It reaffirmed that plaintiff testimony counts as evidence, that hostile work environments are measured by cumulative degradation, and that retaliation can be inferred from timing, selective enforcement, and managerial hostility.

In short, Knox re-centered the Seventh Amendment. It forced the judiciary to respect that disputes of motive and pretext belong to jurors, not gatekeeping judges who see their role as protecting employers from trial.

C. Chislett v. NYC DOE: Monell Revived

The Chislett case tells a parallel story. Leslie Chislett, a veteran DOE administrator, alleged that she was subjected to persistent racial harassment in anti-bias trainings, where “white toxicity” was invoked as an environmental poison and her own authority was undermined through racialized ridicule. When she complained to leadership, she was scolded, ignored, and eventually pushed out.

The district court dismissed her claims as “stray remarks” and “mere insults.” In doing so, it effectively gutted Monell, treating systemic tolerance of harassment as mere workplace banter.

The Second Circuit reversed. It held that a reasonable jury could conclude DOE leadership condoned racial harassment, and that such condonation itself constituted a municipal custom under Monell. Importantly, the appellate panel rejected the district court’s trivialization of systemic hostility. It restored the obvious: repeated tolerance of harassment is policy.

Chislett is not just about race or DEI backlash. It is about judicial humility. It underscores that the judiciary’s role is not to minimize, rationalize, or editorialize plaintiffs’ harms at the threshold. It is to allow jurors to weigh them.

D. Judicial Bias as Stratification’s Ally

Taken together, Knox and Chislett reveal a troubling pattern: district courts are too eager to dismiss claims that challenge institutional power, especially when plaintiffs are marginalized workers or when defendants are powerful municipalities. This eagerness is not doctrinal necessity—it is cultural bias cloaked in legalese.

When judges demand plaintiffs name “final policymakers” at the pleading stage, they are raising hurdles designed to keep cases out. When they discount sworn testimony, they are privileging employers’ paperwork over workers’ voices. When they minimize harassment as “mere insults,” they are dismissing the lived reality of stratification as too ordinary to matter.

These judicial practices do not just harm individual plaintiffs. They erode civil rights law itself, transforming Title VII, § 1981, § 1983, and state analogues into hollow promises. They reinforce the very stratification that phantom grievances distract us from—ensuring that those already disadvantaged by class, geography, and education are further denied access to justice.

E. The Appellate Lifeline

The Second Circuit’s interventions in Knox and Chislett matter not because they rewrite doctrine, but because they restore balance. They remind lower courts that the Seventh Amendment is not optional, that Monell liability is not a dead letter, and that discrimination claims cannot be judged by the comfort level of the bench.

But appellate correction is a fragile lifeline. Most cases never reach appeal. Most plaintiffs cannot afford years of litigation. And most district court dismissals stand unchallenged, quietly reinforcing the stratified status quo.

This is the cost of judicial gatekeeping: systemic inequality is reproduced under the guise of judicial efficiency, while the jury—the constitutional factfinder—is sidelined.

IV. The Cost of Distraction

The fixation on phantom grievances—“reverse racism,” contrived claims of Christian persecution, and the weaponization of DEI backlash—comes at a steep cost. These narratives do not just distort public conversation; they actively undermine the integrity of civil rights enforcement and embolden structural inequality.

A. Dilution of Civil Rights Law

Civil rights statutes were crafted to address systemic inequities rooted in history, power, and institutional practice. Title VII, § 1981, § 1983, the NYSHRL, and the NYCHRL are meant to dismantle entrenched barriers. Yet when courts and agencies are flooded with claims that repurpose those laws to litigate every perceived slight from members of dominant groups, the statutes lose their force.

The doctrine becomes muddied. Judges, overwhelmed by noise, grow skeptical of all discrimination claims. “Reverse racism” cases are wielded as proof that civil rights laws have outlived their usefulness, rather than as evidence of their adaptability. Meanwhile, legitimate claims rooted in systemic harm are drowned out or trivialized.

The result is a civil rights jurisprudence that treats every grievance as equal in theory, but none as actionable in practice. The law becomes performative rather than protective.

B. Diversion of Legal and Institutional Resources

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), state agencies, and municipal human rights commissions all operate under resource constraints. When those resources are consumed investigating dubious claims of majority-group oppression, less capacity remains to pursue entrenched inequities—housing discrimination, systemic wage theft, predatory policing, or institutional harassment.

This diversion is not accidental. It is strategic. By overwhelming enforcement mechanisms with phantom claims, powerholders ensure that real claims languish. Justice delayed becomes justice denied.

C. Judicial Hostility and the Seventh Amendment’s Erosion

As Knox and Chislett demonstrate, district courts are increasingly hostile to civil rights plaintiffs. That hostility is not neutral; it is part of the distraction. When courts wave away racialized harassment as “stray remarks” or dismiss sworn testimony as “self-serving,” they are not applying law—they are reinforcing stratification.

The cost here is constitutional. The Seventh Amendment right to a jury trial is being eroded under the guise of judicial efficiency. When courts decide facts on summary judgment, they usurp the jury’s role and transform Rule 56 into a substitute trial. The appellate reversals in Knox and Chislett are important, but they are exceptions. For every case corrected on appeal, dozens more are extinguished in silence.

D. Erosion of Public Trust

Perhaps the most corrosive cost of distraction is the erosion of public trust in the legal system. When every group lays claim to victimhood—often with media amplification—the public grows cynical about the entire enterprise of civil rights.

The laundromat worker who lost her job after racial harassment is treated as no different from the executive who sues over a diversity training he found uncomfortable. The administrator driven out of DOE is equated with the majority employee claiming “reverse discrimination” because a promotion went elsewhere.

This false equivalence feeds cynicism: if everyone is a victim, then no one is. Civil rights become another partisan battlefield rather than a bulwark of equal justice. The courts, seen as complicit in amplifying phantom grievances while stifling genuine ones, lose legitimacy in the eyes of those most dependent on their protection.

E. Stratification Deepens

The ultimate cost is stratification itself. While we fight over shadows, the machinery of inequality hums along.

Wages stagnate. Schools segregate. Housing markets stratify. Policing systems punish the poor while insulating the powerful. In the NYPD’s Candidate Assessment Division, psychological “unfitness” labels are weaponized to filter out applicants, often under dubious pretexts. In the Aviation Division, bureaucratic silence shields misconduct. These are not cultural skirmishes—they are institutional mechanisms of stratification.

And yet, they rarely dominate headlines or dockets. Instead, the legal system and media ecosystem chase phantom grievances, leaving the real architecture of inequality unchallenged.

V. Conclusion: Stop Fighting Shadows, Face the Machine

America is in danger of mistaking shadow for substance. Phantom grievances—“reverse racism,” inflated claims of Christian persecution, and the hollow panic over DEI—are shadow puppets projected on the wall. They capture attention, stir outrage, and polarize debate. But they are not the fire. The real blaze consuming our democracy is the hardening architecture of social stratification, reinforced daily by institutions that privilege some and dispossess others.

The cost of this misdirection is profound. Civil rights statutes, born of struggle, are diluted when they become vehicles for the already-empowered to claim oppression. Agencies meant to police systemic inequity are distracted by phantom complaints. District courts, emboldened by skepticism, convert Rule 56 into a veto on civil rights claims, forgetting that the Seventh Amendment reserves factfinding to juries.

Knox v. CRC Management Co. and Chislett v. NYC DOE show us both the peril and the possibility. In each, a district court short-circuited the jury’s role—dismissing sworn testimony, trivializing persistent harassment, and substituting judicial doubt for factual inquiry. In each, the Second Circuit intervened to restore balance, reminding us that credibility is for juries and condonation is policy. Yet the fact that appellate correction was even necessary reveals the depth of the problem. For every Knox and Chislett resurrected on appeal, countless other claims die quietly in the district courts.

The Seventh Amendment is not a procedural nicety. It is a structural guarantee that ordinary citizens, not insulated judges, are the arbiters of fact. When courts arrogate that role under the banner of efficiency or skepticism, they are not protecting judicial economy—they are dismantling constitutional rights. And when they do so in the context of civil rights, the effect is doubly corrosive: victims are denied justice, and the public sees civil rights law as hollow.

Meanwhile, the true machinery of inequality churns on. Wage theft and economic exploitation grind down workers. Housing policies stratify neighborhoods. Education systems reproduce class hierarchies. Police agencies—from the NYPD’s Candidate Assessment Division to its Aviation Division—deploy opaque, unaccountable practices that filter opportunity for some while shielding misconduct for others. These are the structural realities that define life chances. Yet they are consistently eclipsed by media “hit pieces” about phantom grievances and partisan fights over DEI trainings.

We must make a choice. Continue shadow-boxing with phantoms, or turn and confront the machine. The fight is not about who can claim the mantle of victimhood most loudly. It is about dismantling the hardened structures of advantage and disadvantage that dictate whose cases get heard, whose voices are silenced, and whose children inherit opportunity.

The appellate rebukes in Knox and Chislett are more than isolated rulings. They are reminders that law, when faithful to its design, can still pierce the shadows. They caution us against judicial overreach, against conflating phantom grievance with genuine harm, and against letting civil rights wither in the name of expedience.

The path forward requires clarity. Stop fighting shadows. Face the machine.