Executive Summary

Body-worn cameras were sold as a transparency breakthrough. But the central problem in modern excessive-force litigation is that cameras did not eliminate disputes—they relocated them into the evidence system itself. The determinative question is not simply whether an encounter was recorded. It is whether the institution can produce a complete, verifiable record that can withstand adversarial testing.

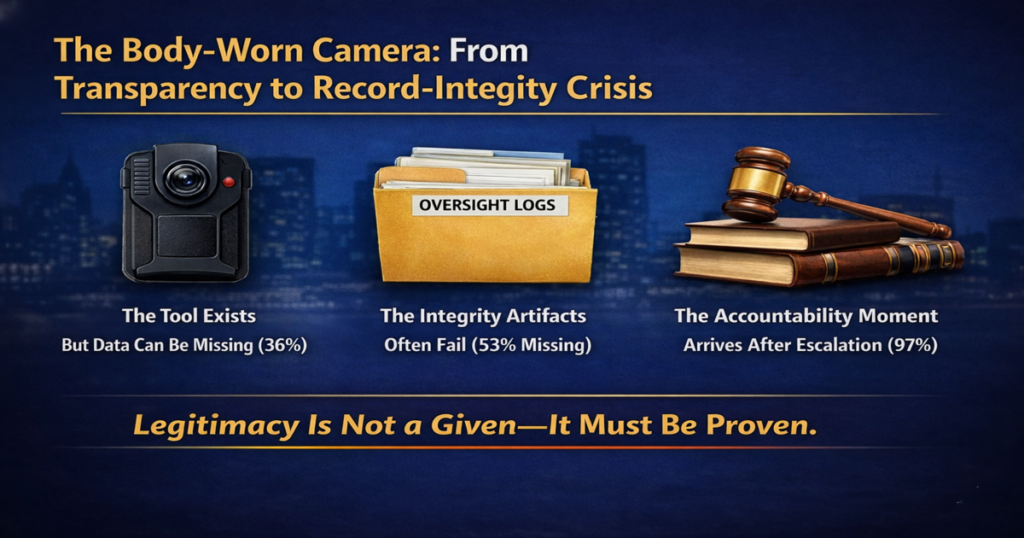

The New York City Comptroller’s October 28, 2025 audit of NYPD’s body-worn camera program makes the record-integrity problem concrete. The Comptroller’s review assessed NYPD’s implementation and oversight of BWCs—including internal use of footage to evaluate use of force and stop legitimacy—and NYPD’s responsiveness to FOIL requests for footage. The Comptroller found that NYPD does not provide BWC footage in response to FOIL requests in a timely manner and that footage often is not produced unless an appeal is filed or litigation is commenced. The audit’s “Key Takeaways” quantify the delay: NYPD took an average of 133 business days to grant or deny FOIL requests, and the longest time to grant or deny a FOIL request during the review period was four years. The Comptroller also reports that NYPD’s FOIL appeal process resulted in production 97% of the time, and that footage was provided after court challenges 92% of the time.

Beyond public access, the Comptroller finds structural weaknesses in NYPD’s internal oversight: activation rates “are lower than they should be,” NYPD does not make full use of footage for compliance, and footage was “missing and incomplete.” Those conclusions matter directly for excessive-force litigation because they identify the precise failure modes that make discovery contentious: missing recordings, incomplete recordings, and weak monitoring controls that impede verification of whether footage should exist and whether it captures the incident in full.

Two additional sources reinforce that the central hinge is not the presence of cameras but the constraint of discretion and the accountability mechanisms that police the record pipeline. The federal Monitor’s reporting emphasizes that meaningful accountability requires sustained and focused efforts; absent consequences and supervisory accountability, compliance tools cannot deliver durable reform. And national empirical research finds that measurable reductions in police-involved homicides concentrate in agencies with stricter activation requirements, while discretionary activation regimes do not yield a significant drop—underscoring that cameras work as accountability only when activation rules limit discretion.

This thought-piece uses these anchors to make a practical claim for the public and the legal community: BWC evidence is only as credible as the integrity of the record system that produces it. The piece reframes the task from “produce the video” to “prove the record”—focusing on activation compliance, completeness, classification/categorization, oversight controls, and the audit trail that shows who accessed or exported footage and when. When those integrity supports are missing, “transparency” becomes conditional on institutional choice—and accountability becomes optional.

I. Cameras Didn’t End Disputes—They Relocated Them Into the Evidence System

The public story of body-worn cameras is simple: record the encounter and the truth will be obvious. It’s a story born from exhaustion—exhaustion with contradictory accounts, with official narratives that carry institutional weight, and with courtroom outcomes that often turn on who is believed rather than what can be proven.

But the courtroom reality is that cameras did not eliminate disputes. They rearranged them.

They moved the dispute away from the event itself and into the evidence system that decides what the event becomes in litigation: what was recorded, when recording began, whether it ran continuously, how it was categorized, whether required reviews happened, what got preserved, and what ultimately appears in discovery. The encounter is still the moral center of the story, but the record pipeline has become the legal center.

This relocation is not a lawyer’s abstraction. It is a human dynamic that anyone who has ever watched people argue about a high-stakes moment will recognize: memory is elastic under stress; perception is partial; fear and adrenaline distort time; and authority often sounds more “coherent” than vulnerability. A body-worn camera was supposed to counteract those fragilities by anchoring the story in something objective.

But objectivity does not appear automatically because a device exists. Objectivity has conditions: activation, continuity, preservation, and verifiable integrity. When those conditions fail, the camera doesn’t resolve disputes—it creates a new category of dispute: not “what happened,” but “what exists,” and more pointedly, “what is missing.”

That missingness matters because the law does not like vacuums, and neither do juries. When the video stops early, starts late, is absent, or appears incomplete, the trial stops being a straightforward fact-finding exercise and becomes a credibility contest. The jurors begin to read between the lines, and “between the lines” is where institutions often regain the advantage: the government can argue error, malfunction, human forgetfulness, or workload; the plaintiff is left arguing inference, pattern, and common sense.

This is why record integrity is not a technical side issue—it is the foundation of whether adjudication is actually adversarial in a meaningful way.

The Comptroller’s audit gives this dynamic a hard, non-speculative grounding. The Comptroller reports that NYPD’s oversight over the BWC program “needs improvement,” that activation rates are “lower than they should be,” and—critically for litigation and public legitimacy—that footage was “missing and incomplete,” and that NYPD does not consistently conduct reviews of footage or collect related documentation required by policy and procedure.

That single sentence does more than criticize performance. It describes a structural condition that transforms litigation: a world where the record is not reliably whole and where compliance mechanisms intended to ensure integrity are not consistently executed.

The Comptroller goes further, supplying measurable indicators of the very failure modes lawyers routinely confront under the heading “camera issues.” For footage that was on file, auditors found that BWCs were activated late and/or deactivated early—recording stopped before the incident ended—18% of the time. If nearly one in five recordings ends early or begins late, the question is no longer whether cameras exist. The question becomes whether the program produces a record that can consistently bear the weight the public places on it.

The audit also describes a fundamental oversight weakness: self-inspections for BWC activation were not conducted for 53% of sampled months, and the department did not consistently perform required supervisory reviews and aggregation needed to identify trends and anomalies. That matters because integrity is not a one-time event. It is a discipline—something sustained through routine review, clear accountability, and trend visibility. If the integrity apparatus is sporadic, then “missing footage” is not an exception; it is a predictable output.

The human dynamic becomes unavoidable here. People want to believe that missing footage must mean intentional concealment, because concealment is narratively satisfying—it provides a villain. But the more corrosive reality is often bureaucratic: when a system is large and oversight is inconsistent, integrity failures can arise from habit, diffusion of responsibility, and misaligned incentives. Those forces don’t produce a villain; they produce something more dangerous: a system where accountability becomes optional without anyone ever needing to “choose” corruption.

This is why the public conversation about BWCs frequently feels stuck. The public asks, “Why don’t the cameras solve it?” Police leadership answers with more training, more policies, more reminders. Critics answer with more suspicion. But the actual problem sits in a colder place: the record pipeline is an administrative machine, and administrative machines require governance. Where governance is weak, integrity erodes; where integrity erodes, disputes relocate; where disputes relocate, truth becomes negotiable.

This thought-piece is written for the public and the legal community because both communities—often without realizing it—are now litigating the same underlying question:

Is the body-worn camera program a transparency tool, or is it a narrative tool?

The camera itself cannot answer that. The evidence system can. And the evidence system is tested in one place more than any other: discovery.

II. NYPD Already Uses BWC Footage as Internal Supervision—So Why Does Litigation Still Feel Like a Scavenger Hunt?

If the public wants proof that body-worn cameras are not merely symbolic, it should look at how NYPD uses them internally. The Federal Monitor’s report describes ComplianceStat as a program designed to hold command leadership accountable for the lawfulness of stops, frisks, searches, and undocumented stops, with commanders expected to explain deficiencies identified through bureau-level audits.

And the report describes, in plain terms, that before a ComplianceStat meeting, the Patrol Services Bureau reviewed “numerous” body-worn camera videos and identified poor performance across several indicators, including failures to complete stop reports and consent-to-search forms.

That matters because it removes a common excuse embedded in discovery disputes: the implication that video is too hard to find, too fragmented to review, too burdensome to treat as a compliance instrument. Here, the Monitor describes the Patrol Services Bureau reviewing “numerous” videos as a routine part of a structured accountability process. In other words: NYPD’s internal system already behaves as though BWC footage is a governance asset.

But the same Monitor narrative also captures something that is essential to a deep understanding of BWC disputes: identifying problems is not the same as enforcing consequences. The first ComplianceStat described in the report produced what the Monitor calls an insufficient response, with only one member removed from a special-team assignment. A second ComplianceStat followed, with additional video review again identifying poor performance, and the command response again largely limited to instruction or retraining.

Only after escalation—by the third ComplianceStat—did the report describe more significant corrective action, including command discipline, removals from assignment, command changes, and in one command, disbanding a team. The Monitor’s report explicitly frames those improvements as the product of targeted and sustained effort.

This is the heart of the human dynamic behind BWC programs: the camera introduces visibility, but visibility does not automatically generate accountability. Accountability requires a system willing to impose consequences, to treat repeat failures as governance failures, and to sustain attention beyond the first wave of scrutiny.

Now bring that back into the litigation context.

In an excessive-force case, the plaintiff is not merely seeking a clip for dramatic effect. The plaintiff is seeking to test whether the state’s version of the event is supported by a reliable record. But the experience of many litigators is that discovery too often feels like negotiating for fragments: a partial video, a missing angle, a “camera malfunction” label without corroborating review documentation, a late activation at the most critical moment, a deactivation before the incident resolves.

The Comptroller’s audit suggests that this is not simply anecdotal frustration—it is consistent with systemic oversight deficiencies. The audit states that required reviews of BWC activation were not conducted, that NYPD lacks independent reviews of activation rates, and that NYPD does not consistently conduct reviews of footage or collect related documentation required by policy and procedure. It further states that self-inspections for activation were missing for 53% of sampled months and that NYPD does not aggregate results to identify anomalies or trends.

Read those lines together and a pattern emerges that is highly consequential for force litigation: even if a command believes it is “doing oversight,” the system may not be generating the integrity artifacts needed to prove that oversight occurred, that trends were identified, and that repeat failures were addressed.

The audit also reports a striking data point tied directly to the existence of footage: auditors aggregated NYPD’s BWC footage reviews and determined that footage was not on file for 36% of incidents in the dataset. The Comptroller simultaneously reports that for footage that was on file, late activation and/or early deactivation occurred 18% of the time. These are not marginal error rates. These are the kinds of rates that, in litigation, convert a “video case” into a “record integrity case.”

At this point, the thought-piece can’t stay at the level of policy aspiration. We have to say what this does to human beings inside the system and outside it.

For the officer, activation can feel like a burden imposed amid fast-moving, volatile encounters. For supervisors, enforcement can feel like triage: the command has too many competing priorities, and enforcement choices are shaped by what leadership emphasizes. For the institution, footage can feel like exposure, and the natural institutional instinct is to manage exposure. For the public, footage is supposed to be an equalizer—something that prevents power from controlling the narrative. For plaintiffs, footage is often the only impartial witness. And for jurors, footage functions as a moral compass: they want it, and when it’s missing, they want to know why.

So the question becomes: what kind of institution does NYPD want to be, and what kind of institution can the law allow it to be? An institution that uses footage for internal management while producing incomplete records when accountability becomes adversarial cannot realistically call that “transparency.” It is a two-tier system: internal visibility, external gatekeeping.

And that is where the FOIL story belongs—not as the spine, but as the public-facing mirror of the same structural phenomenon.

The Comptroller reports that NYPD does not provide BWC footage in response to FOIL requests timely and frequently does not provide footage without appeals first being filed; in most instances where NYPD did not initially provide footage timely, it eventually did provide it after an internal appeal or court challenge. The audit quantifies this delay: on average, NYPD took 133 business days to grant or deny FOIL requests, ranging up to more than four years (1,076 business days). The report also states that 97% of appealed denials were granted and that 92% of court challenges resulted in NYPD providing the footage (either mandated or to settle).

Those are public-access metrics, not civil discovery metrics—but the institutional behavior is familiar: production comes late, and often only after escalation. This is why FOIL belongs in the piece as supporting context: it makes the integrity dispute legible to non-lawyers. The public understands delay, denial, appeal, court challenge, and sudden production. It understands what it means when the record appears only after pressure.

And once readers grasp that dynamic, you can lead them into the legal heart of the piece: discovery is the formal version of that same struggle. The court’s role is to prevent “pressure” from being the only route to the truth.

Section II ends with the pivot we need for the next chapter:

If cameras are governance infrastructure, then the legal system cannot treat “a clip” as transparency. The legal system must treat BWCs as part of a record-making system that must be auditable—because without auditability, the state remains the author of its own narrative.

III. The Policy Hinge: Cameras Change Behavior Only When Discretion Shrinks

Once you stop treating body-worn cameras as a symbol and start treating them as a system, the first question becomes brutally simple: who controls when the camera “exists”? If the officer controls that decision in the moments that matter most, the camera is not an independent witness. It is a conditional narrator. And conditional narrators do not settle disputes; they generate them.

The Kim study is valuable here because it does something the public debate rarely does: it separates “camera adoption” from the actual institutional design that determines whether adoption means anything. In its own abstract, the study says the effects of BWC adoption are heterogeneous and that reductions in police-involved homicides are concentrated in agencies with stricter activation requirements, while agencies with weaker policies do not show measurable change; it also states the study finds “no significant trade-offs” in overall arrest or crime rates. This is the correct way to talk about cameras to a general audience: not as a miracle or a failure, but as a tool whose impact depends on whether policy constrains discretion and whether the organization can actually enforce that policy.

The paper then gives a concrete illustration that reads like a warning label for any legal system that treats “we have BWCs” as the end of the analysis. It reports that activation mandates vary widely across contexts: while the vast majority of agencies require activation in one-on-one engagements with civilians (up to 94%), fewer agencies mandate activation for other scenarios that still involve officer discretion, and the requirement drops to 26.4% for policing public events. Read that slowly. A camera system can be mandatory in the easy, individualized contexts yet far less mandatory in contexts that are volatile, crowded, politically sensitive, and prone to contested narratives. That is not a trivial detail; it is exactly where legitimacy crises tend to occur.

For the public, the implication is intuitive: the most consequential encounters are often the least reliably recorded when activation rules are porous. For litigators, the implication is sharper: if the policy regime makes activation discretionary in high-stakes contexts, then the absence of footage cannot be treated as a rare anomaly. It becomes a foreseeable product of design.

Kim then operationalizes “stricter activation” in a way that matters for policy and proof. The study categorizes agencies into two groups based on activation policy: those that require officers to activate BWCs in seven or more types of events out of ten possible scenarios, and those with less stringent requirements. That is important because it shows the difference between a program that says “use the camera” and a program that says “the camera is required in the routine decision points where discretion otherwise dominates.” It is the difference between encouragement and compulsion.

When the paper runs the heterogeneity analysis, it reports that agencies with more comprehensive activation requirements drive the results, with a decrease in police-involved homicides, while those with less stringent requirements did not experience a significant drop. The study also frames this as a broader lesson: the “importance of an agency’s BWC policy in shaping the effects of BWC implementation.” For our purposes, that line is not a statistical flourish; it’s a bridge between public expectations and courtroom reality. People think the camera is the reform. The evidence says the policy architecture—particularly activation requirements—is the reform.

Now connect that national insight to what the Comptroller found locally. The Comptroller’s report states that NYPD’s oversight needs improvement, that activation rates are “lower than they should be,” that footage was “missing and incomplete,” and that NYPD does not consistently conduct reviews or collect required documentation. That is the same hinge the Kim paper identifies, but expressed in the governance language of an audit rather than the econometric language of an academic article. The tool exists; the integrity conditions fail.

The Comptroller’s audit then quantifies the way discretion and weak monitoring surface in practice. Auditors aggregated the results of NYPD’s BWC footage reviews and determined that footage was not on file for 36% of incidents in the dataset; for footage that was on file, BWCs were activated late and/or deactivated early 18% of the time. This is exactly the terrain where activation policy becomes a courtroom issue. A system that frequently produces late activation or early deactivation isn’t merely dealing with “technical hiccups.” It’s producing evidentiary gaps that will inevitably be filled with institutional explanation and adversarial inference.

The most important public lesson here is not that cameras “work” or “don’t work.” It is that cameras operate as accountability only when they are not optional in the very contexts where accountability is most contested. The most important legal lesson is even more practical: when activation is not reliably required and reliably enforced, the evidentiary record becomes negotiable, and discovery becomes the arena where the negotiability is either exposed or normalized.

This is where the human dynamic returns. Officers experience the camera as surveillance. Supervisors experience it as a performance metric. Command leadership experiences it as risk management. Plaintiffs experience it as a lifeline. Jurors experience it as a moral anchor. But a program that treats activation as “administrative compliance” rather than a constitutional safeguard invites a specific failure mode: the camera becomes a tool of legitimacy when it helps the institution, and an “unfortunate absence” when it would constrain the institution. The law cannot allow accountability to be conditional in that way without corroding its own legitimacy.

That is why this thought-piece insists on a disciplined reframe: a body-worn camera program is not primarily a technology issue. It is a discretion-management issue. It is a governance issue. It is a record-integrity issue. And the measure of its seriousness is whether the institution can produce the integrity artifacts—activation compliance, completeness, and auditability—when the system is tested by litigation.

IV. Workflow Not Window: How “The Video” Is Manufactured Before It Ever Reaches Court

A common public mistake is to think that the legal dispute is about watching a video. In practice, the legal dispute is about reconstructing the path that produced the video you were shown and identifying what was filtered out along the way.

The moment you accept that “video is a record pipeline,” you begin to see why discovery is so often the real battleground in force cases. A pipeline can break in quiet ways. A pipeline can also produce outputs that look official and reliable even when critical integrity checks failed. And most importantly: a pipeline can create gaps that are later explained as one-off errors even when those gaps are statistically common.

The Comptroller’s audit provides an unusually clear starting point for describing this pipeline in human terms. It states that the objectives of the review were to assess NYPD’s implementation and oversight of the BWC program, including its internal use of footage to evaluate use of force and the legitimacy of stops, and its compliance with FOIL requests for BWC footage. That framing matters because it confirms the central proposition: this program is supposed to generate evidence that can be used both internally (supervision, evaluation, legitimacy checks) and externally (public access, accountability). When a system has dual audiences, the integrity standards must be higher, not lower, because the temptation to manage the narrative grows with the stakes.

The pipeline begins with capture, but capture is not just “camera on.” It’s camera on at the right moment, with continuity, through the full incident, with the context that makes the later footage legible. The Comptroller’s report describes NYPD’s ICAD audits of dispatched 911 calls to determine whether officers recorded incidents in their entirety, as required, and notes that the results are communicated to commands for further investigation and remediation. That means the organization itself treats “recorded in its entirety” as a compliance expectation. Yet in the same section, the auditors report that footage was not on file for 36% of incidents and that late activation or early deactivation occurred 18% of the time for footage that was on file.

To a juror, those numbers translate into a simple experience: the video often begins after the story is already in motion or ends before the story resolves. That is the worst possible design for a system intended to resolve contested encounters, because it amplifies the very disputes the camera was supposed to settle. It forces the decision-maker to adjudicate not only what is seen, but what is not seen, and to decide which party should bear the risk of the unseen portion.

After capture comes oversight. Oversight is where integrity becomes enforceable rather than aspirational. Here, the Comptroller’s findings are not about subjective “commitment.” They are about missing governance artifacts. The audit states that self-inspections for BWC activation were not conducted for 53% of sampled months and that NYPD did not ensure the required review chain occurred; it also states that NYPD does not independently review BWC footage to identify use-of-force incidents and does not ensure required TRI reports are filed when force is used, meaning that BWC footage is also not reviewed. A program can have cameras, but if the institution cannot prove it performed the routine checks that make noncompliance detectable, then the system’s reliability becomes a matter of faith rather than verification.

The Comptroller’s report also explains why this oversight gap is not just paperwork. It states that because NYPD does not perform trend analysis of activation data, its effectiveness and ability to adapt is hindered, and it has limited assurance that officers who consistently activate BWCs improperly are identified or that corrective action is taken when necessary. That is a governance failure with a predictable downstream effect: the same officers can repeat the same activation failures, and the system cannot reliably prove it detected and corrected the pattern. In litigation, that translates into an environment where “late activation” and “malfunction” narratives remain plausible because the integrity system cannot demonstrate that it systematically polices those narratives.

The report becomes even more concrete when it describes NYPD’s own stated limitation: NYPD told auditors that “trend analysis of late activation/early deactivation is not accomplished with a data pull” and that assessing proper activation requires watching the entire video for context, something done only on an ad hoc basis for ComplianceStat and not scalable to the numerous videos captured yearly. The Comptroller then disputes that claim, noting that auditors were able to aggregate and perform trend analysis of ICAD reviews and calling NYPD’s “cannot be scaled up” claim “dubious.” The stakes of that disagreement are not academic. If an institution treats scalability as an excuse for non-analysis, it structurally accepts a world where integrity failures are not systematically identified. That is a design choice. And design choices are not neutral when constitutional rights depend on the record.

The Monitor’s report, from a different angle, illuminates the same reality: the organization can review numerous videos and identify poor performance indicators, but sustained change requires leadership to demand accountability and impose consequences. It also warns that compliance oversight plans are overly concentrated on administrative issues such as proper BWC activation and categorization rather than emphasizing constitutional policing and freedom from racial bias. That is a familiar institutional trap. A department can build a robust pipeline for checking whether boxes were ticked—activation, categorization, form completion—while remaining weaker on the harder question: whether the pipeline is producing records that can resolve contested constitutional encounters rather than merely documenting administrative effort.

This is why the “workflow not window” frame is not rhetorical flourish. It is the only frame that explains why the public can be told “we have cameras,” why internal oversight can include video review, and yet why litigators and courts still end up fighting over gaps, incompleteness, and missing integrity artifacts. The existence of cameras is not the question. The integrity of the pipeline is.

Once readers internalize that, they are prepared for the next move: understanding how the record can be shaped without anyone ever “editing” the footage in the way the public imagines. The shaping happens through capture conditions, oversight failures, classification choices, and production decisions—the architecture of what becomes “the evidence.”

V. The Three Quiet Failure Modes: Capture, Oversight, and Production as Narrative Control

A body-worn camera system does not need fraud to fail. It needs only a set of predictable weak points that allow a record to become incomplete and then allow that incompleteness to be normalized. In excessive-force litigation, those weak points show up repeatedly, and the Comptroller’s audit gives them an unusually grounded vocabulary: missing footage, late activation, early deactivation, missing self-inspections, missing required reviews, and lack of trend analysis.

The first failure mode is capture failure, and capture failure is rarely presented as a policy failure. It is presented as an accident, a momentary lapse, or a technical mishap. But the Comptroller’s audit describes a pattern that makes capture failure a recurring structural problem rather than a rare exception: auditors aggregated NYPD’s own BWC footage review results and concluded that footage was not on file for 36% of incidents in the dataset; for footage that was on file, late activation and/or early deactivation occurred 18% of the time. A system with those rates cannot be treated as though “the camera will show what happened” is a safe assumption. It is not safe. It is conditional.

The human consequence of capture failure is predictable and deeply unfair: the most contested and volatile moments—moments where the public most needs objective evidence—are the moments most likely to be missing context, missing continuity, or missing entirely. The jury is then asked to decide which party should bear the risk of that missingness. That risk allocation is the hidden moral question in modern force trials.

The second failure mode is oversight failure. Oversight failure is what turns capture failure from a correctable issue into a permanent vulnerability. The Comptroller found that self-inspections for BWC activation were not conducted for 53% of sampled months and that NYPD did not ensure required reviews occurred, including reviews of stop reports and related footage and independent review mechanisms to identify use-of-force incidents; it also reports NYPD does not aggregate review results to identify anomalies or trends. The report then explains the practical consequence: because NYPD does not perform trend analysis, it has limited assurance that officers who consistently activate BWCs improperly are identified and that corrective action is taken.

This is where “human dynamic” becomes institutional reality. In any large organization, people optimize for what is measured and enforced. When a department cannot reliably prove it reviewed the right material at the right cadence, and cannot reliably prove it aggregated results to detect patterns, it creates an incentive environment where repeat failures can persist without consequence. That is not an accusation of bad faith; it is the standard way complex systems drift when governance tools are incomplete. The report’s detail about missing self-inspection records illustrates how that drift looks in practice. Auditors requested self-inspections from 11 randomly selected precincts for three months across five years—165 individual months—and NYPD was unable to provide self-inspections for 87 of those months, “more than half.” The point here is not that paperwork was missing. The point is that an integrity mechanism designed to detect whether officers recorded incidents in their entirety could not be reliably proven to exist in the records when auditors asked for it. That is exactly the kind of governance gap that later becomes a discovery fight: the institution offers an assurance (“we do reviews”), but the integrity artifacts needed to verify the assurance are absent.

The third failure mode is production failure, which includes both public production and litigation production. Even when footage exists and even when a review process exists, an institution can still control the narrative by controlling how the evidence reaches outsiders and under what conditions. The Comptroller’s report—while focused on FOIL—describes a pattern that mirrors what litigators experience: NYPD does not provide BWC footage in response to FOIL requests timely and frequently does not provide footage without appeals first being filed; in most instances, the department eventually provides it following appeal or after court challenges. The audit then quantifies escalation dynamics: NYPD took an average of 133 business days to grant or deny FOIL requests, and 97% of BWC footage appeals were granted; auditors identified 13 court challenges related to BWC denials, and 12 of those resulted in NYPD providing footage or being ordered to do so.

Because FOIL is a supporting chapter rather than the spine of this thought-piece, the key lesson to extract is narrow and powerful: when production is delayed and frequently requires escalation, the system sends a message about who controls access to the record and under what pressure. That message travels. It shapes public confidence, and it shapes litigation expectations. It also reinforces the central thesis of the piece: transparency is not just the presence of recording devices; it is the readiness and integrity of production when the record is demanded.

The Monitor’s report adds a final layer that makes these three failure modes morally legible. It warns that ComplianceStat will not be effective and sustained change will not occur until NYPD leadership demands accountability through consistent and focused effort. It also warns that oversight plans can become overly concentrated on administrative issues such as proper BWC activation and categorization rather than emphasizing constitutional policing free from racial bias. Those warnings are not limited to stop-and-frisk oversight. They are a general diagnostic for why integrity systems fail: compliance becomes performative when consequences are inconsistent and when the organization substitutes administrative indicators for constitutional outcomes.

Section V ends where it should: at the threshold of the discovery chapter. Once you understand these failure modes, the next question becomes unavoidable for both the public and the legal community: what does it take—in a force case—to test whether any given recording is complete, authentic, properly categorized, and produced with an integrity trail that can withstand adversarial scrutiny?

That is where Section VI begins, and it’s where your practical litigation reality becomes the public’s education: “produce the video” is not the demand; “prove the record” is.

VI. Discovery That Actually Tests Integrity: From “Produce the Video” to “Prove the Record”

In an excessive-force case, the phrase “body-worn camera footage” is deceptively simple. It suggests there is a single object—the video—that can be produced, watched, and argued over. But the Comptroller’s audit and the Monitor’s report together teach a more mature truth: what matters is not merely whether footage exists, but whether the institution can prove the integrity of the record system that created what you are seeing.

The Comptroller found precisely the kinds of integrity failures that turn discovery into the real battleground: footage was “missing and incomplete,” activation rates were “lower than they should be,” and NYPD did not consistently conduct reviews or collect documentation required by policy and procedure. That is not merely a criticism of performance. It is a direct warning to courts: do not treat “a clip” as self-authenticating transparency in a system where the internal checks that validate completeness are inconsistent.

The problem is compounded by the audit’s quantified findings. Auditors aggregated NYPD’s BWC review results and found that footage was not on file for 36% of incidents in the dataset; when footage was on file, cameras were activated late or deactivated early 18% of the time. This is the key empirical basis for the discovery posture this thought-piece urges: if missingness and truncation are not rare, then “record integrity” must be treated as a standard discovery inquiry, not as a special accusation reserved for scandalous cases.

Now add the governance layer. The Comptroller reports that self-inspections for BWC activation were missing for 53% of sampled months and that NYPD did not aggregate results to identify anomalies or trends; it further explains that without trend analysis, NYPD has limited assurance it can identify officers who consistently activate improperly or ensure corrective action is taken. In plain English: the organization’s ability to detect repeat failure is weakened, and the institution’s ability to demonstrate that it policed activation failures is weakened. In litigation, that means a court should expect “activation issues” to recur, and should expect that the integrity artifacts necessary to verify explanations may be incomplete.

The Monitor’s report supplies a complementary institutional reality: NYPD uses video review in internal oversight, and its ComplianceStat framework is designed to hold commands accountable for lawful policing; commanders must explain deficiencies identified in bureau-level audits. But the Monitor also warns that sustained change will not occur without consistent leadership demands for accountability, and it cautions that oversight plans can become overly focused on administrative metrics like activation/categorization rather than constitutional outcomes. These points matter for discovery because they describe a system where video review can exist while enforcement of integrity remains uneven, and where administrative compliance can substitute for deeper constitutional accountability.

Against that backdrop, the correct discovery frame is neither paranoid nor indulgent. It is proportional. It is the minimal set of requests necessary to transform “a video” into “evidence.”

What follows is the practical principle that should govern discovery in every force case: you do not ask only for footage; you ask for the integrity artifacts that allow the footage to be tested. That is the difference between transparency and theater.

The first integrity artifact is completeness. If auditors can find that footage is not on file for 36% of incidents, then in a litigated force case the parties and the court must start from a reasonable premise: the nonexistence of footage is not self-proving, and the existence of footage is not proof of completeness. Completeness must be tested through demands that reveal whether the record should exist, whether it exists in full, and whether it was recorded “in its entirety,” which is itself treated as a compliance expectation in NYPD’s ICAD audit process.

For discovery, that means the fundamental question is not “did you give me a file?” The question is: did you give me the entire encounter as the system was designed to capture it, and can you prove that? The answer cannot be a conclusory statement. It must be supported by records, because the Comptroller’s audit shows that the very processes that would substantiate compliance—self-inspections, supervisory reviews, trend analysis—are not reliably performed or retained.

The second integrity artifact is continuity. Even when footage exists, late activation and early deactivation undermine the narrative value of the recording. Auditors found this occurred 18% of the time for footage that was on file. A late activation is not a minor error if it consistently removes the very moments that define the legality of force—approach, commands, resistance, escalation. An early deactivation is not a minor error if it deletes the resolution—handcuffing, medical attention, post-force statements, recovery, or the absence of threats that might justify continued force.

Discovery should therefore include not only “the incident clip,” but the segments that make the incident intelligible: pre-contact context, the full use-of-force sequence, and the post-incident tail. This is not a demand for volume. It is a demand for narrative continuity—because continuity is where legality lives.

The third integrity artifact is the review chain. The Comptroller’s audit identifies systemic gaps in required self-inspections and reviews. It also reports that NYPD does not independently review footage to identify use-of-force incidents and does not ensure required TRI reports are filed when force is used, which means footage is not reviewed. That matters for discovery because a reviewing institution should be able to show what it did with a use-of-force recording: who reviewed it, when, for what purpose, and what, if anything, was flagged. When the review chain is missing or inconsistent, the court loses a critical integrity check—an internal confirmation that the record was treated as evidence and that anomalies were identified.

Discovery should therefore demand the records that show whether a review chain existed for the incident. Not because internal review determines legality, but because internal review—or the absence of it—helps establish the institutional handling of the evidence. In a mature accountability system, the organization should be able to demonstrate that use-of-force footage triggered the internal processes designed to evaluate it. When it cannot, the court should treat that inability as relevant to the reliability of the evidentiary record.

The fourth integrity artifact is aggregation and trend analysis. This is where the Comptroller audit becomes especially relevant to litigation practice. NYPD told auditors that trend analysis of late activation and early deactivation is not accomplished through data pulls and that assessing proper activation requires watching entire videos, a process only done ad hoc for ComplianceStat and not scalable to the large number of annual recordings; the Comptroller found this claim “dubious” because auditors were able to aggregate and trend-analyze ICAD review results. That dispute reveals a critical litigation point: institutions may treat scalability as a reason to avoid building integrity analytics. But discovery—especially in force cases—should not allow scalability limitations to become a shield. If the system generates compliance review results, those results can be aggregated and used to identify repeat failures.

Why does this matter in an individual case? Because the absence of trend analysis creates a predictable litigation move: every integrity failure is framed as isolated. The camera malfunctioned. The officer forgot. The battery died. The upload failed. Without trend analytics and oversight records, plaintiffs are forced to argue pattern without the institutional data that would confirm or refute it. The Comptroller’s audit makes clear that NYPD’s limited trend analysis reduces assurance that repeat offenders are identified and corrected. That is not just bad administration; it is a structural condition that affects the fairness of adjudication.

The fifth integrity artifact is accountability consequences. The Monitor’s reporting is particularly valuable here because it illustrates how oversight works only when repeated failures produce escalated responses. The Monitor describes repeated ComplianceStat cycles where video review identified poor performance and initial responses were limited to instruction or retraining; meaningful change came only after escalation, discipline, removals, and disbanding a team, with the Monitor emphasizing that improvement requires targeted and sustained effort. The lesson for discovery is simple: if consequences are inconsistent, noncompliance persists, and evidentiary integrity becomes unreliable. A court evaluating missing footage or late activation cannot treat it as merely “unfortunate” if the institution’s own accountability system is not designed or enforced to prevent recurrence.

At this point, the public version of discovery becomes legible. Discovery is not “lawyer games.” Discovery is the mechanism by which the justice system tests whether a state institution is offering a record that can be trusted. The Comptroller’s findings that footage is missing and incomplete, that activation is late or ends early, and that the review and monitoring apparatus is inconsistent, are the factual foundation for why discovery must be structured as a record-integrity audit in force cases.

That brings us to the practical shift that lawyers should push and courts should normalize: an integrity-first discovery protocol. Not as a punitive presumption, but as a standard checklist. The checklist is not complicated conceptually, even if its implementation can be technically detailed. It asks: what footage should exist, what footage exists, whether it is complete, who reviewed it, and what records demonstrate those facts. The Comptroller’s audit shows why that checklist is not optional—it is the only rational response to a system where missingness, truncation, and oversight gaps are documented.

Finally, because FOIL is only supporting here, it plays one specific role in Section VI: it demonstrates, in a public context, that record access often arrives after escalation. The Comptroller reports that NYPD frequently does not provide footage timely without appeals, and that footage was often provided after internal appeal or court challenge. That pattern matters because it shows that “pressure-based transparency” is not a hypothetical risk. It is a documented reality in the public-access channel. The legal system cannot import that culture into civil discovery without allowing accountability to become conditional on the plaintiff’s resources and persistence.

Section VI therefore lands on the principle that should guide the remainder of this essay: if the city wants the legitimacy benefit of body-worn cameras, it must accept the legitimacy cost of verifiable integrity. A camera program that produces missing footage, late activation, and inconsistent monitoring cannot be treated as conclusive transparency. The institution must be required to prove its record.

That is not a rhetorical demand. It is the minimum condition for fairness in a system where liberty and life can turn on what exists in the file.

VII. FOIL as a Supporting Mirror: When “Transparency” Arrives Only After Escalation

FOIL is not the spine of this thought-piece, but it is the most accessible way to show the general public what litigators already experience in civil discovery: the record does not always move freely just because it exists. The Comptroller’s audit assesses NYPD’s responsiveness to FOIL requests for body-worn camera footage and reports a pattern that should trouble anyone who believes cameras automatically deliver transparency. The audit states that NYPD does not provide BWC footage in response to FOIL requests in a timely manner and that footage is frequently not provided unless an appeal is filed or litigation is commenced; in most instances, where footage was not initially provided timely, it was ultimately produced after an internal appeal or a court challenge.

The power of FOIL as a supporting chapter is that it makes “record gatekeeping” legible without legal jargon. People understand what it means to ask for a public record, be delayed or denied, and then suddenly receive the material after pushing harder. The Comptroller quantified that escalation dynamic. It reports that NYPD took an average of 133 business days to grant or deny FOIL requests for BWC footage during the period reviewed, and that the longest time to grant or deny a request was more than four years (1,076 business days). Those numbers are not merely administrative inefficiency. They describe a practical reality: the public often cannot evaluate government conduct in anything close to real time, and accountability becomes delayed until it becomes less costly to the institution.

What matters most is not only the delay, but what happens when the requester refuses to accept the first answer. The Comptroller reports that NYPD’s FOIL appeal process resulted in the requested footage being provided 97% of the time, and that when denials were challenged in court, NYPD provided the footage (either pursuant to a court directive or to settle) 92% of the time. That is the signature of a system in which the first decision is often not the final decision—and where production is frequently the product of escalation rather than routine compliance.

This matters to the public because it reframes what “transparency” actually means in practice. Transparency is not a press release about cameras. Transparency is the institutional habit of producing records promptly and consistently, without making citizens run a procedural gauntlet. When production arrives mainly after appeal or court pressure, transparency becomes conditional. It becomes something you can access if you have time, stamina, and resources. That is not equal access. It is stratified access.

For the legal community, FOIL’s significance here is narrower but sharper: it is a mirror that shows how institutional control over records can persist even in a regime built on presumptive public access. If that is the pattern in FOIL—an access mechanism specifically designed for disclosure—then courts should not be surprised that civil discovery in high-stakes force cases can devolve into the same escalation dynamic: partial production, delayed production, production only after motion practice, and a persistent fight over what the “record” really is.

The point is not to equate FOIL to discovery. They are different systems with different legal standards. The point is to show continuity in institutional behavior that the public can grasp. In both settings, the camera does not automatically produce transparency. Transparency is produced by governance—by enforceable rules, supervision, and consequences for noncompliance. And where the Comptroller finds that footage is frequently not provided timely without appeals or litigation, the public should understand why litigators insist that “produce the video” is not enough. The demand is—and must be—“prove the record,” because without proof, access can be delayed, conditioned, and controlled.