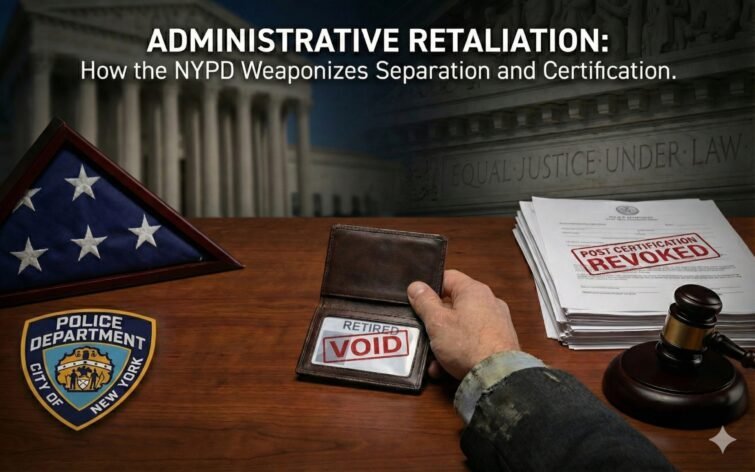

In December 2025, I published Administrative Retaliation: How the NYPD Weaponizes Separation and Certification, a thought-piece grounded in years of representing officers whose service ended not with dignity, but with erasure. That essay advanced a simple proposition: control does not end when employment ends. It merely changes form.

Retired identification cards withheld.

POST certifications revoked or stalled.

“Good standing” replaced with silent disqualification.

The mechanism was administrative.

The effect was punitive.

At the time, some dismissed the analysis as theoretical. Others treated it as advocacy. A few insisted that post-employment credentials were merely discretionary—revocable privileges beyond judicial scrutiny.

That argument no longer survives.

A recent federal decision out of the Eastern District of New York confirms, in painstaking detail, that administrative retaliation at exit is not only real—it is unconstitutional.

When Courts Stop Pretending Credentials Are “Favors”

In Perros v. County of Nassau, the court confronted a practice strikingly similar to what I described in my December blog. Retired officers—many forced out by line-of-duty injuries—were systematically denied required “good guy” letters, a prerequisite to obtaining retired firearm permits and maintaining professional standing.

The defense advanced a familiar narrative: discretion, safety, individualized judgment.

The court rejected it entirely.

Judge Gary R. Brown found that the denial of these credentials was not discretionary, not individualized, and not benign. It was systematic retaliation, implemented as a matter of policy by a final decisionmaker. The credentials were not ceremonial. They were gateways—without which former officers were publicly marked, professionally isolated, and exposed to danger.

The opinion did something critical: it refused to treat exit-stage credentials as administrative afterthoughts. Instead, it recognized them for what they are—extensions of employment power, capable of inflicting constitutional harm.

Systematic Retaliation Is Policy, Not Coincidence

One of the most important confirmations in Perros is doctrinal. The court did not analyze the case as a series of bad decisions. It analyzed it as institutional conduct.

The Sheriff—Michael Sposato—was found to be a final policymaker. His repeated denial of credentials to disabled retirees was not an aberration; it was a customary practice. And because it was carried out by a final policymaker, the County itself was liable under Monell.

This point cannot be overstated.

For years, departments have relied on fragmentation—spreading responsibility across bureaus, units, and procedures—to avoid accountability. Perros collapses that strategy. When retaliation is consistent, targeted, and tolerated, it becomes policy. And when it becomes policy, municipalities answer for it.

Targeting Disability at the Moment of Exit

The factual core of Perros also mirrors a recurring pattern in police employment litigation: disability as a trigger for retaliation.

The court found explicit animus toward officers who retired on disability pensions. These were not officers deemed unsafe or unqualified. Medical evaluations repeatedly confirmed their fitness to possess firearms. Yet they were denied credentials solely because of how they exited service.

That finding matters because it exposes the underlying logic of administrative retaliation. Exit is not punished because of risk—it is punished because it challenges institutional narratives about loyalty, sacrifice, and control. Disability retirement, in particular, disrupts those narratives. It converts injury into entitlement. And entitlement, in bureaucratic cultures, is often met with resentment.

The “Scarlet Letter” Effect Is Not Metaphorical

In my earlier blog, I described exit-stage retaliation as a “professional death sentence.” Perros gives that phrase evidentiary grounding.

The court credited testimony describing:

Retired credentials with a blue background, signaling disgrace or danger

Public humiliation in front of peers and civilians

Encounters with former inmates while stripped of lawful means of self-protection

Reputational damage that followed officers into civilian life

Judge Brown explicitly likened these credentials to a “scarlet letter”—visible from a distance, understood within law enforcement culture, and devastating in consequence.

This was not symbolic harm. It was operational harm. And the court treated it as such.

Damages That Reflect Moral Condemnation

The remedy in Perros is as significant as the holding.

The court awarded $283,000 to six plaintiffs:

$133,000 in compensatory damages, jointly against the County and the Sheriff, for emotional distress, humiliation, and safety risks

$150,000 in punitive damages, imposed personally against the Sheriff, reflecting findings of deceit, animus, and deliberate indifference

Punitive damages were not incidental. They were moral judgment. The court described the conduct as reprehensible, vindictive, and systematic—language rarely used lightly in § 1983 cases.

Even more striking: the County agreed to indemnify the punitive damages, notwithstanding longstanding public policy disfavoring such indemnification. That decision speaks volumes about institutional alignment—and institutional risk.

The Detail That Should Alarm Every Oversight Body

There is one fact in Perros that deserves far more attention than it has received.

After the County conceded liability for unconstitutional retaliation, the same individual was reappointed as Commissioner of Corrections—restored to authority over the very processes the court found to be abused.

That is not oversight failure.

That is institutional indifference.

It confirms the thesis at the heart of my December blog: administrative retaliation persists not because it is hidden, but because it is tolerated.

What This Means for NYPD Exit Practices

Perros does not involve the NYPD. It does not need to.

Its legal conclusions apply with equal force to any department that:

Conditions exit credentials on silence or compliance

Uses certification or identification as leverage

Treats separation as the end of constitutional obligation

The law now says otherwise.

Federal courts are making clear that dignity at exit is not aspirational. It is enforceable. And when departments convert administrative processes into tools of reprisal, they expose themselves—and their municipalities—to direct constitutional liability.

The Final Measure of Power

Institutions often claim legitimacy by pointing to how they hire, train, and discipline. Courts are beginning to apply a different metric.

How does power behave when it is no longer needed?

Perros answers that question. And it confirms what too many former officers have already learned the hard way: the last act of public service is the final test of lawful governance.

Dignity at exit is not ceremonial.

It is constitutional.

And now, it is judicially affirmed.