Dedication

This thought-piece is dedicated to Retired Lieutenant Quathisha Epps, Detective Specialist Jaenice Smith, Retired Police Officer Nicholas Hernandez, and the thousands of outgoing employees—retirees, vested members, and even those terminated—who have faced retaliation for simply separating from service.

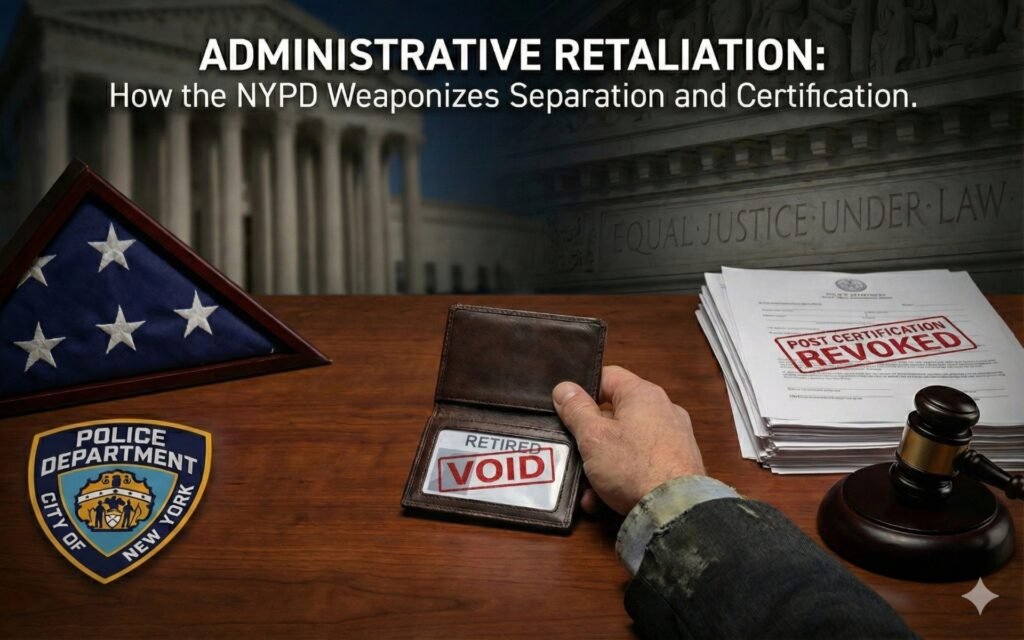

Their stories are not anomalies; they are evidence of a system that too often confuses loyalty with silence and treats departure as dissent. Each of them served under the same oath they were later denied the dignity to complete. Each earned the right to leave with respect, yet instead confronted bureaucratic retribution masquerading as policy—denied their retired identification cards, stripped of Police Officer Standards and Training (POST) certification, and publicly diminished by the very institution that once relied upon their service.

Their stories are also chapters in a longer narrative—the persistence of systems that protect themselves even as they punish those who once upheld them.

They represent the unseen casualties of administrative power—those whose years of duty end not with ceremony but with paperwork and exclusion. Their experiences expose a broader truth about modern policing: that control does not end at resignation, retirement, or termination. It continues through the manipulation of credentials, the withholding of recognition, and the quiet erasure of professional identity.

This work is written for them—and for the principle that the rule of law must govern even the last act of public service.

Because dignity at exit is not a privilege; it is the final promise of a lawful career.

Executive Summary

The quiet denial of dignity at exit is among the least examined abuses of power in modern policing. When public employees complete their service—whether by retirement, vesting, or separation through disciplinary resolution—the law presumes closure under established standards. Yet in practice, too many find themselves punished for leaving: stripped of retired identification cards, having their POST certification revoked, or being branded ‘ineligible’ for future employment without any lawful basis. These practices transform administrative discretion into retaliation and reduce statutory rights to privileges dispensed at will.

Under federal law, such conduct implicates Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and 42 U.S.C. § 1983, particularly when decisions to deny recognition or revocation of their Police Officer Standards and Training (POST) certification are driven by bias, retaliation, or deliberate indifference. When an agency applies standards inconsistently, weaponizes credentials, or targets individuals who have engaged in protected activity, it crosses from managerial authority into civil-rights violation. Courts have long held that public employers cannot disguise punishment as policy; the Monell doctrine—recently reaffirmed in Chislett v. New York City Department of Education, 157 F.4th 172 (2d Cir. 2025)—makes municipalities answerable under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 when unconstitutional conduct arises from an official policy, entrenched custom, or persistent practice rather than from isolated or aberrational acts.

Under state law, the New York State Human Rights Law (Executive Law §§ 290–301) independently prohibits discriminatory or retaliatory conduct affecting the “terms, conditions, or privileges of employment.” The 2019 amendments—mandating liberal construction and rejecting the “severe or pervasive” threshold—expand liability to encompass post-employment retaliation and denial of benefits linked to protected activity or status. A lawful separation cannot be followed by administrative retribution without violating Executive Law § 296.

Under local law, the New York City Human Rights Law (Administrative Code § 8-101 et seq.) provides even broader protection, forbidding any act that “tends to deprive” individuals of opportunity. The revocation of credentials or denial of retired status on arbitrary or retaliatory grounds meets that definition squarely. These acts also undermine the City’s own diversity and inclusion objectives by signaling that dissent or disfavor carries permanent professional consequences.

The cumulative effect is a culture of institutional reprisal: a system that enforces silence through fear of post-service punishment. This thought-piece argues that such conduct is not merely unethical—it is unlawful. The same laws that guarantee equal opportunity at entry also safeguard dignity at exit. Administrative retaliation against those who have already served corrodes both the rule of law and the legitimacy of the institutions sworn to uphold it.

Because the true measure of professional integrity is not how government hires—but how it lets people go.

I. Federal Framework — Title VII, § 1983, and Monell

At the federal level, the denial of retired identification cards, revocation of Police Officer Standards and Training (POST) certification, or other punitive acts imposed upon outgoing employees implicate two overlapping bodies of law: (1) Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq., which prohibits discrimination and retaliation in all aspects of employment, and (2) 42 U.S.C. § 1983, which provides a civil remedy for the deprivation of federal rights under color of state law. When such conduct is institutionalized—rather than the product of isolated misjudgment—the Monell doctrine renders the municipality itself answerable.

A. Title VII — Retaliation and Post-Employment Protection

Title VII extends beyond hiring and discharge; it encompasses “the entire spectrum of disparate treatment in employment.” See Hishon v. King & Spalding, 467 U.S. 69, 75 (1984). Federal courts have long recognized that retaliatory or discriminatory acts occurring after separation can still constitute unlawful “terms, conditions, or privileges of employment.” See Robinson v. Shell Oil Co., 519 U.S. 337, 346 (1997) (holding that “employees” under Title VII include former employees subjected to post-employment retaliation).

Accordingly, when a police agency withholds a retired identification card, revokes POST certification, or otherwise interferes with post-service employment opportunities in response to protected activity—such as filing complaints, testifying, or simply exercising the right to separate from service—it violates Title VII’s anti-retaliation provision, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-3(a). The Supreme Court has emphasized that retaliation provisions must be interpreted broadly to prohibit any employer conduct “reasonably likely to deter” protected activity. Burlington N. & Santa Fe Ry. Co. v. White, 548 U.S. 53, 68 (2006). Administrative punishment at the point of exit—by denying credentials or recognition—plainly meets that standard.

Moreover, Title VII’s disparate-impact doctrine, first articulated in Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971), and codified at 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(k), applies where ostensibly neutral post-employment policies (such as discretionary credential revocations) disproportionately affect protected groups. Absent demonstrable business necessity and empirical validation, such practices are unlawful.

B. 42 U.S.C. § 1983 — Constitutional Violations Under Color of Law

Even where Title VII provides a statutory remedy, § 1983 supplies an additional constitutional cause of action when government officials act under color of state law to deprive individuals of rights secured by the Constitution or federal statutes. Denial of credentials or professional certification for retaliatory, arbitrary, or discriminatory reasons implicates multiple constitutional guarantees:

Equal Protection Clause — Unequal treatment based on impermissible classification violates the Fourteenth Amendment. See Village of Willowbrook v. Olech, 528 U.S. 562 (2000) (per curiam).

First Amendment Retaliation — Penalizing employees or former employees for speech, association, or petitioning activity offends the First Amendment. See Garcetti v. Ceballos, 547 U.S. 410 (2006).

Due Process Clause — Where a statutory or regulatory entitlement to certification or recognition exists, revocation without notice or hearing contravenes procedural due process. See Cleveland Bd. of Educ. v. Loudermill, 470 U.S. 532 (1985).

Because these actions are undertaken by state actors—department officials or municipal agencies—§ 1983 provides the vehicle for redress.

C. Monell Liability — Institutional Accountability

The Supreme Court’s decision in Monell v. Department of Social Services of the City of New York, 436 U.S. 658 (1978), established that municipalities may be sued under § 1983 when a constitutional violation results from an official policy, entrenched custom, or deliberate indifference to known unlawful practices. The doctrine rejects vicarious liability yet imposes institutional responsibility where misconduct reflects organizational will rather than individual error.

The Second Circuit recently reaffirmed these principles in Chislett v. New York City Department of Education, 157 F.4th 172 (2d Cir. 2025), holding that “persistent and widespread practices” maintained through the “constructive acquiescence of senior policymakers” can establish a de facto municipal policy. Id. at 180–81. Chislett thus underscores that official inaction in the face of known illegality is functionally indistinguishable from formal adoption.

Applied here, if the NYPD, through its leadership, systematically withholds retired identification cards, decertifies officers, or manipulates exit credentials as a retaliatory or disciplinary device, such conduct constitutes an unconstitutional custom maintained with deliberate indifference. Under Monell and Chislett, the City itself bears liability—not merely the individual officials involved.

D. The Federal Principle

Federal law imposes a single, unambiguous rule: public authority ends where constitutional and statutory rights begin. An agency cannot wield administrative discretion as a weapon against those who separate from service. When post-employment retaliation becomes policy—whether written or customary—it violates both Title VII and the Constitution, triggering § 1983 and Monell liability.

The federal framework therefore establishes the foundation for accountability: the right to leave government service without forfeiting one’s dignity, credentials, or professional future is not aspirational—it is enforceable under the supreme law of the land.

II. State Framework — The New York State Human Rights Law and Statutory Entitlements

The New York State Human Rights Law (NYSHRL), codified at Executive Law §§ 290–301, serves as the state’s broad declaration that discrimination in employment—by public or private employers—is a matter of public concern and state policy. Its coverage extends to “all persons within the jurisdiction of this state,” ensuring that the opportunity to obtain and retain employment is free from “discrimination because of race, creed, color, national origin, sex, age, disability, or marital status.” N.Y. Exec. Law § 291(1).

While historically interpreted in tandem with federal standards, the NYSHRL was fundamentally reshaped by the 2019 legislative amendments (L. 2019, ch. 160), which deliberately broke from federal precedent to impose broader protections and lower evidentiary thresholds for claimants. The Legislature’s directive that the statute “be construed liberally for the accomplishment of the remedial purposes thereof, regardless of whether federal civil rights laws … have been so construed” id. § 300, marked a profound shift in interpretive philosophy. Under this framework, New York’s state-law protections operate as an independent civil-rights charter—particularly in the public employment context.

A. Post-Employment Retaliation and Continuing Jurisdiction

The 2019 amendments codified what had already been emerging through judicial construction: that the NYSHRL protects not only current employees but also former employees subjected to post-employment retaliation or interference with professional standing. In McHenry v. Fox News Network, LLC, 510 F. Supp. 3d 51, 68 (S.D.N.Y. 2020), the court recognized that retaliatory post-employment actions—such as reputational sabotage or credential interference—fall within the ambit of the amended NYSHRL. Likewise, Golston-Green v. City of New York, 184 A.D.3d 24, 39 (2d Dep’t 2020), held that the statute “must be interpreted broadly to effectuate its remedial purpose” and no longer incorporates the restrictive federal concepts of “severe or pervasive” conduct or temporal limitation.

Accordingly, when a public employer such as the NYPD denies a retired identification card, obstructs access to POST certification, or otherwise interferes with the ability of a separating officer to obtain comparable employment, those actions constitute adverse employment consequences within the meaning of Executive Law § 296(1)(a). Because the NYSHRL now explicitly prohibits retaliation “in any manner against any person” who has opposed discriminatory practices, id. § 296(7), the statute captures retaliatory conduct that occurs after separation, provided it is causally related to the employment relationship.

B. Disparate Impact and Absence of Validation

New York’s state courts have long aligned the NYSHRL with the Griggs principle that ostensibly neutral practices yielding disproportionate harm to protected groups require empirical validation. In People v. New York City Transit Authority, 59 N.Y.2d 343, 349 (1983), the Court of Appeals held that “a neutral employment practice that happens to have a disparate impact on a protected group is unlawful unless it is shown to be job-related.”

When a police department employs credential-revocation procedures or discretionary identification denials that disproportionately affect older, female, or minority officers—particularly those who have filed prior complaints—the absence of a validated, neutral rationale renders such conduct presumptively unlawful under Executive Law § 296(1)(a). In this regard, the NYSHRL dovetails with federal disparate-impact analysis under 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(k) but without the procedural constraints or burden-shifting limitations of Title VII.

C. Procedural and Substantive Rights to Certification and Recognition

Beyond the anti-discrimination mandate, the NYSHRL operates in tandem with the New York Civil Service Law and the Professional Policing Act of 2021, both of which establish objective criteria for police qualification and certification. Once a police officer satisfies the state’s training, fitness, and certification standards, those credentials constitute a protected property and professional interest under state law. Arbitrary denial or revocation—particularly as reprisal for lawful separation or whistleblowing—violates both Executive Law § 296(1) and the procedural-due-process guarantees embedded in Civil Service Law §§ 75–76.

By withholding retired identification cards or revoking POST certification without stated cause, notice, or hearing, the NYPD and the City of New York engage in precisely the kind of discretionary abuse that the Legislature sought to eliminate. The 2019 amendments to the NYSHRL amplify that intent: public employers now bear the affirmative duty to ensure that their employment and post-employment actions are free from even the appearance of discrimination or retaliation.

D. Remedies and Oversight

The remedial architecture of the NYSHRL provides multiple enforcement pathways. Claimants may pursue administrative relief before the New York State Division of Human Rights (DHR) or bring direct judicial action under Executive Law § 297(9). The statute authorizes compensatory damages, civil fines, and injunctive relief, including orders requiring reinstatement or restoration of credentials wrongfully withheld. In cases involving willful violation or reckless indifference, the DHR or the court may also impose punitive penalties under § 297(4)(c).

For police personnel, the DHR’s jurisdiction coexists with that of the Civil Service Commission, the Municipal Police Training Council (MPTC), and the Division of Criminal Justice Services (DCJS), each of which remains accountable to the Legislature and Governor for ensuring adherence to uniform standards. When a department’s internal policy conflicts with those statutory mandates, oversight bodies retain the authority to order corrective action and refer systemic violations to the Attorney General for enforcement under Executive Law § 63(1).

E. The State Principle

The NYSHRL’s post-2019 structure transforms what was once a reactive statute into a proactive instrument of equal governance. It commands that public employers prevent—not merely respond to—discrimination and retaliation. It rejects the notion that separation from service terminates the State’s interest in fairness or equality.

Thus, when a police department uses administrative tools—credential denial, ID withholding, certification revocation—as leverage or punishment against departing employees, it violates not only federal law but the State’s explicit legislative commitment to equitable treatment. Under New York law, dignity at exit is a statutory right, not a courtesy, and its violation carries both moral and legal consequence.

III. Local Liability — The NYCHRL’s Independent Mandate

The New York City Human Rights Law (NYCHRL), Admin. Code § 8-101 et seq., extends the most expansive protection against discriminatory employment practices within the five boroughs. Enacted through the 2005 Restoration Act and strengthened by later amendments, the NYCHRL must be construed “liberally for the accomplishment of the law’s uniquely broad and remedial purposes.” (Williams v. New York City Hous. Auth., 61 A.D.3d 62 [1st Dep’t 2009].)

Unlike Title VII or the NYSHRL, the NYCHRL dispenses with rigid burden-shifting. Under Mihalik v. Credit Agricole Cheuvreux N.A., Inc., 715 F.3d 102 (2d Cir. 2013), an employer violates the statute whenever its conduct “tends to deprive” a person of employment opportunities, even absent intent. This standard applies fully to municipal employers, including the NYPD, which acts as an agency of the City itself.

Accordingly, the denial of a retired identification card, the revocation of POST certification, or the selective withholding of credentials for employees exiting service—whether by retirement, vesting, or settlement—constitutes actionable discrimination where it makes continued employment in the security or law-enforcement field “less well available” to members of protected classes. (Admin. Code § 8-107(1)(a).) Remedies under § 8-502 include injunctive relief, reinstatement of credentials, compensatory damages, and attorney’s fees.

The NYCHRL thus serves as the City’s own mirror: it compels the government that enforces equal-protection principles to embody them internally. Where the NYPD weaponizes credentialing against dissent or disfavored groups, municipal liability follows not as punishment, but as restoration of the rule of law.

IV. Institutional and Policy Implications

The legal violations described above reflect more than isolated misconduct; they expose systemic defects in New York’s administrative architecture. Credential revocation and ID denials are not random—they are tools of institutional control that persist because oversight remains diffuse and accountability fragmented.

At the state level, neither the Civil Service Law nor Executive Law § 837 vests any agency with direct enforcement power over such practices. This vacuum allows departments to treat credentialing as internal privilege rather than legal right. At the municipal level, the City Council’s Committees on Public Safety and Civil and Human Rights possess subpoena authority under Charter § 29 to investigate patterns of discriminatory exit practices and to refer findings to the Department of Investigation (DOI). Their inaction perpetuates the same culture of silence that retaliatory credentialing seeks to enforce.

Fiscal implications follow close behind. Each unlawful denial of credentials invites federal and state liability, triggering compensatory and punitive exposure—and, if systemic, the possibility of federal monitoring or consent-decree oversight under Title VII or 42 U.S.C. § 1983. The New York City Law Department and Comptroller must therefore treat compliance as a mandatory legal duty—not an internal personnel matter.

True reform requires structural transparency. The City should codify a uniform credential-issuance policy, publish data on all denials and revocations, and establish independent review under the Department of Investigation or DCAS. Only when credentialing decisions are auditable can they cease to serve as instruments of reprisal.

V. Conclusion — Dignity at Exit as a Legal Imperative

The right to leave public service without retaliation is as fundamental as the right to serve. The NYPD’s manipulation of retired identification cards and POST certifications transform separation into sanction, contradicting every principle embedded in federal, state, and local civil-rights law.

Under Title VII and § 1983, such acts constitute retaliatory deprivation of rights under color of law. Under the NYSHRL, they violate Executive Law § 296(1)(a) by imposing disparate impact without validation. Under the NYCHRL, they “tend to deprive” former employees of equal opportunity in violation of Admin. Code § 8-107. Across all frameworks, the common denominator is arbitrariness—a hallmark of discrimination.

Reform begins where retaliation ends. Every retiring, vesting, or separated employee is entitled to the same procedural dignity that governed their appointment: fairness, transparency, and equal treatment under the law. Until those guarantees are institutionalized, New York’s largest police agency will continue to model selective legality rather than lawful governance.

Because dignity at exit is not ceremonial—it is constitutional. It is the final test of whether public power remains accountable to the public it serves.