Kristin Cabot. Paige Shiver. Lieutenant Quathisha Epps. And How Power, Race, and Institutional Self-Preservation Decide Credibility

Executive Summary

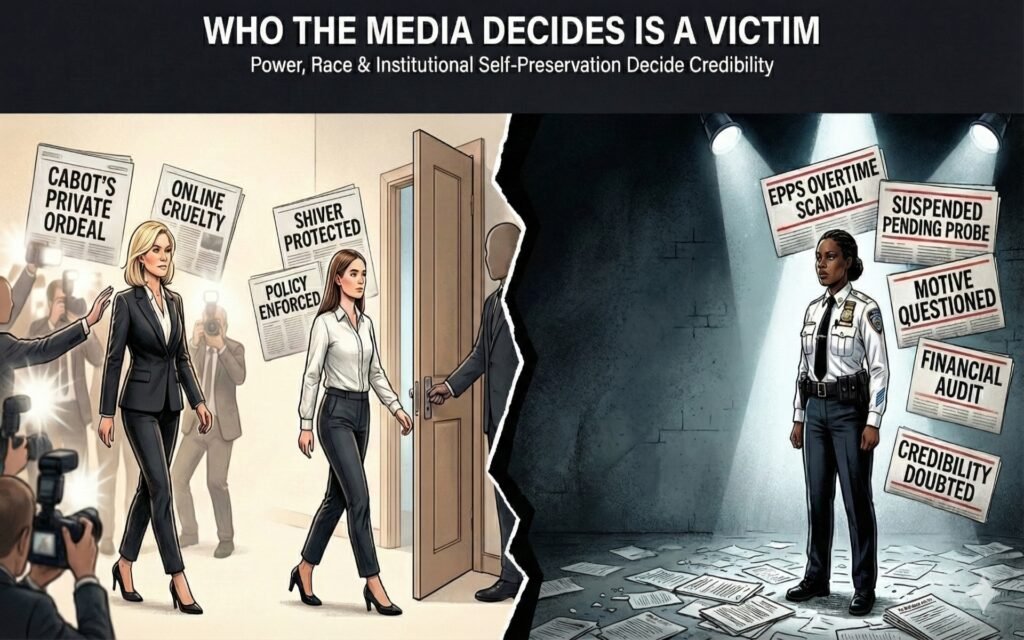

Sexual-harassment law does not collapse because the rules are unclear. It collapses because credibility is rationed—early, quietly, and unevenly—before any formal process begins. Long before a court weighs evidence or an investigator interviews witnesses, institutions and the media make an implicit threshold decision: which woman is allowed to be believed without having to survive the consequences of disclosure.

This commentary examines that credibility threshold through three recent public controversies: Kristin Cabot, Paige Shiver, and Lieutenant Quathisha Epps. These are not the same case and do not involve identical facts. But together they reveal a consistent structural pattern in how credibility is assigned—and how power, race, and institutional self-preservation determine whether the response to sexual-harassment allegations becomes protection or punishment.

In Cabot’s case, credibility functions as a shield. Her denial is treated as a framing fact rather than a claim requiring scrutiny, and the narrative centers on reputational harm and public cruelty. The institution appears measured, humane, and stabilizing; structural questions about power and accountability recede. In Shiver’s case, institutional responsibility is assigned upward. The power imbalance is acknowledged, policy enforcement is applied as written, and the subordinate is not converted into a target of discipline or credibility prosecution. In both cases, the institutional posture reflects an ability to contain reputational risk without punishing the woman at the center of the story.

Lieutenant Quathisha Epps’ case illustrates the opposite: the immediate collapse of presumed credibility when the allegations threaten the institution itself. Rather than centering the power imbalance between the highest-ranking uniformed NYPD official and a lieutenant subordinate, the public frame shifts quickly to Epps—her finances, timing, and supposed motives. From there, the institutional response becomes procedural retaliation: suspension, investigative saturation, payroll-based reframing, reputational attack, and post-employment credential harm. In modern institutional cases, retaliation rarely announces itself as punishment; it migrates through “process,” leveraging administrative tools—audits, investigations, and licensing consequences—to make protected activity professionally radioactive.

This commentary argues that credibility is not a fact-finding outcome. It is an institutional decision. Once credibility is conferred, institutions narrow their response and stabilize the narrative. Once credibility is withheld, institutions expand process, manufacture collateral suspicions, and launder retaliation through compliance. The result is a two-track system: belief is granted when it is cheap and withheld when it is costly—especially when the complainant is a Black woman accusing powerful leadership.

The legal bottom line is straightforward. Civil-rights law prohibits retaliation not only in obvious forms, but in cumulative procedural forms that would deter a reasonable person from reporting misconduct. When institutions respond to sexual-harassment complaints by suspending the reporter, escalating collateral investigations, fueling narrative criminalization, and impairing post-employment standing, they are not enforcing the law—they are protecting themselves. The question is not who is telling the truth. It is who is allowed to be believed long enough for the truth to matter.

I. Introduction

Sexual-harassment law does not fail at the margins. It fails at the gate.

Before a court evaluates evidence, before investigators interview witnesses, and long before liability is assessed, a quieter determination is made: whose allegation is entitled to credibility without proof, and whose must earn belief through survival. That determination is rarely articulated, but it is decisive. Once made, it shapes every institutional response that follows.

Credibility is not merely a cultural concept; it is the first enforcement mechanism in civil-rights law—determining whether protection is triggered or withheld before any formal process begins. It determines whether an allegation triggers protection or suspicion, whether power is interrogated or insulated, and whether the institution turns outward in accountability or inward in defense. Although statutes purport to be neutral, credibility is distributed unevenly in practice—shaped by race, institutional hierarchy, and the perceived cost of exposure.

The phrase ‘who is believed’ is often treated as a matter of public sentiment. It is not. It is a legal threshold. Disbelief does not merely injure reputation; it restructures institutional conduct. It determines who is suspended, who is investigated, who is isolated, and who ultimately bears the professional and personal consequences of disclosure.

Over the past year, three public controversies have exposed this mechanism with uncommon clarity. They are not the same case. They do not involve identical allegations or factual postures. But they illuminate the same structural truth:

A white executive woman who denies a relationship is framed as a victim of public cruelty.

A white subordinate woman in an acknowledged supervisor–subordinate relationship is protected by institutional policy.

A Black woman alleging repeated sexual coercion by the most powerful official in her organization is met with skepticism, scrutiny, and institutional countermeasures.

This commentary does not purport to adjudicate truth. That function belongs to fact-finders. What it examines instead is how institutions and media decide whose credibility is presumed and whose must be proven, and how that decision—made early and often implicitly—determines outcomes before formal processes begin.

What follows belief—or the denial of it—is not passive. Institutions do not merely withhold sympathy. They act. They suspend. They investigate. They audit. They recast narratives. They facilitate leaks. They litigate. In modern civil-rights cases, retaliation rarely appears as a single adverse act. It emerges as a pattern of procedural decisions that, taken together, would deter a reasonable person from reporting misconduct.

Race is not an overlay on this process. It is the engine.

The cases of Kristin Cabot, Paige Shiver, and Lieutenant Quathisha Epps demonstrate how credibility is assigned, how responsibility is allocated, and how institutional self-preservation operates when power is threatened. Read together, they reveal not inconsistency, but design.

II. Kristin Cabot and the Architecture of Presumptive Credibility

Kristin Cabot’s case is the point of entry because it reveals how credibility is granted, not tested.

Cabot denies a sexual relationship with her employer. That denial is not treated as a claim requiring corroboration; it is treated as a framing fact. From that moment forward, the analysis proceeds not toward questions of power, influence, or institutional responsibility, but toward reputational harm and public cruelty.

The New York Times article is explicit in its orientation. The central injury is not workplace misconduct; it is viral humiliation. The legal questions that might otherwise arise in a supervisor–subordinate context—conflicts of interest, disclosure obligations, misuse of authority—are present only as background noise. They do not structure the inquiry.

This is not an oversight. It is a function of presumptive credibility.

A. Denial as a Credibility Shield

Cabot’s denial does not trigger skepticism. It resolves it.

The Times does not ask whether denial is strategic, incomplete, or self-protective. It does not interrogate the asymmetry between a chief executive officer and a chief people officer whose professional survival depends on perceived trust. Instead, denial becomes the predicate that allows the story to shift immediately into human-interest terrain.

This matters legally. In civil-rights enforcement, denial by a complainant or participant is not neutral. It functions as a gatekeeping device: once denial is accepted, the institution’s exposure narrows. The inquiry becomes about optics rather than power.

Cabot’s credibility is therefore not examined; it is presumed. And because it is presumed, no investigative urgency follows.

B. The Reframing of Harm

Once credibility is granted, harm is redefined.

The injury Cabot is understood to have suffered is not professional coercion or institutional compromise. It is social annihilation: doxxing, threats, paparazzi, online abuse, and the emotional toll on her children. These harms are real. But their elevation has legal consequence. They displace inquiry into whether the employer’s structure enabled impropriety in the first place.

The institution is portrayed as responsive, measured, and humane. An investigation is conducted. A negotiated resignation occurs. There is no language of discipline, breach, or enforcement. The employer fades into the background as a neutral administrator rather than a regulator of power.

What is striking is not what is said, but what is absent:

No sustained examination of disclosure obligations.

No scrutiny of reporting lines.

No analysis of whether consent is complicated by hierarchy.

These omissions are not accidental. They are permitted because the subject has already been assigned victim status.

C. Executive Proximity and the Disappearance of Power Analysis

Cabot occupies a rare position: she is not merely an employee; she is an executive charged with managing workplace integrity. That role might ordinarily heighten scrutiny. Here, it does the opposite.

Executive proximity functions as insulation. It collapses the distinction between actor and institution. Because Cabot is framed as a peer rather than a subordinate, power asymmetry is neutralized rhetorically. The CEO’s authority is acknowledged, but not interrogated. It is present, but legally inert.

The result is a story about a woman undone by public spectacle, not about a workplace compromised by authority.

D. What Presumptive Credibility Accomplishes

Presumptive credibility accomplishes three things simultaneously:

First, it stabilizes the institution. There is no demand for structural reform because no structural failure is identified.

Second, it confines the narrative to personal consequence rather than institutional responsibility.

Third, it forecloses retaliation analysis entirely. There is no need to examine adverse action because the subject exits on negotiated terms, with dignity intact.

Cabot is not required to prove harm. Harm is assumed. And because harm is assumed, the law recedes.

E. Why This Case Matters

Cabot’s case is not troubling because she is believed. Belief is not the problem. The problem is who is allowed to be believed without inquiry, and what institutional questions are never asked as a result.

Presumptive credibility is invisible to those who benefit from it. But it is decisive. It determines whether power is examined or excused, whether institutions are scrutinized or absolved, and whether the law is invoked or bypassed.

Cabot’s case shows how easily legal inquiry dissolves when credibility is granted at the outset.

The next case shows what happens when institutions do the opposite: when power is acknowledged, responsibility is assigned upward, and credibility is not treated as a trial.

III. Paige Shiver and Institutional Assignment of Responsibility

If Kristin Cabot’s case demonstrates how credibility can be presumed and inquiry narrowed, the University of Michigan’s handling of Paige Shiver demonstrates something different—and rarer: an institution that assigns responsibility upward once power dynamics are exposed.

This distinction matters. Not because Michigan is uniquely virtuous, but because its response illustrates what compliance looks like when credibility is not racialized and institutional self-preservation does not depend on discrediting the subordinate.

A. The Legal Posture: Power Imbalance Acknowledged

In the Shiver matter, the relevant power dynamic was not ambiguous in the way institutions often claim ambiguity. Reporting established an intimate relationship between a head coach and his executive assistant. That alone placed the situation squarely within Michigan’s governing policy framework.

The University of Michigan’s rule—SPG 201.97—is explicit. It prohibits supervisors from initiating or engaging in intimate relationships with individuals they supervise or over whom they exercise professional influence. Critically, the policy places the burden of disclosure and compliance on the supervisor, not the subordinate. It does so precisely because consent is legally compromised by hierarchy.

This allocation of responsibility is not symbolic. It is the backbone of modern employment law. The existence of a power imbalance does not require proof of force or explicit coercion to trigger institutional obligation. The imbalance itself is sufficient.

Michigan treated it that way.

B. Responsibility Assigned Upward

When the relationship became public, the institution did not equivocate. It did not conduct parallel credibility inquiries into the subordinate. It did not suspend or discipline Paige Shiver. It did not launch audits into her compensation, background, or motives as a condition of protection.

Instead, Michigan terminated the supervisor.

That decision is the most legally significant fact in the case. It reflects an institutional determination that responsibility for managing power lies with those who possess it. Shiver was not required to prove exploitation in order to remain employed. The acknowledgment of hierarchy resolved the question.

This is what enforcement looks like when policy is applied as written.

C. Media Scrutiny Without Institutional Conversion

Shiver was subjected to press attention. Tabloids scrutinized her salary increase, her family connections, her medical history, and even her apartment lease. That scrutiny was invasive and, in places, gratuitous.

But the critical point is this: Michigan did not convert media suspicion into institutional punishment.

The university did not retroactively reframe Shiver as a wrongdoer. It did not initiate internal investigations into her credibility. It did not treat press curiosity as a predicate for discipline. The institution drew a line between public noise and legal obligation.

That separation is not common. It is deliberate.

D. Containment Without Retaliation

Michigan’s response also demonstrates how institutions can contain reputational harm without retaliating against complainants or subordinates. The university’s action narrowed the controversy rather than expanding it. It removed the supervisor. It allowed law enforcement to address criminal conduct separately. It did not widen the aperture to engulf the subordinate.

There was no investigatory sprawl. No procedural saturation. No economic coercion. No symbolic exile.

In legal terms, the institution acted in a way that would not deter a reasonable person from reporting misconduct.

E. Why This Case Is the Pivot Point

Shiver’s case is not important because it is dramatic. It is important because it shows that the assignment of responsibility is a choice.

Michigan could have framed the situation as murky. It could have demanded proof of coercion. It could have suspended both parties “pending investigation.” It did none of those things. It followed its policy and the logic of power.

This case therefore stands as a control sample. It demonstrates what happens when an institution accepts that hierarchy distorts consent and acts accordingly.

The contrast with what follows is not accidental.

In the next case, the allegations are more severe, the power differential more extreme, and the institutional stakes far higher. Yet the response moves in the opposite direction.

That is where credibility stops being presumed and starts being litigated.

IV. Lieutenant Quathisha Epps and the Immediate Collapse of Presumed Credibility

Lieutenant Quathisha Epps’ allegations against former NYPD Chief of Department Jeffrey B. Maddrey did not enter the public sphere as a controversy in search of facts. They entered as a credibility problem in search of containment.

That framing decision—made early and reinforced repeatedly—distinguishes this case from both Kristin Cabot’s and Paige Shiver’s, and it explains nearly everything that followed.

A. The Nature of the Allegations

Epps did not allege a consensual relationship later regretted.

She did not allege an “inappropriate relationship.”

She did not allege ambiguity.

She alleged repeated quid pro quo sexual harassment and sexual assaults by the highest-ranking uniformed officer in the New York City Police Department, occurring inside NYPD Headquarters, tied explicitly to overtime, career survival, and financial coercion.

The accused did not deny sexual contact. He denied coercion and asserted consent.

Legally, that distinction does not neutralize power. Under Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 1983, the NYSHRL, and the NYCHRL, consent asserted by a supervisor does not dissolve coercion where professional leverage exists—particularly where economic vulnerability is alleged.

And yet, from the moment the allegations became public, the inquiry did not center on power.

It centered on Epps.

B. The Immediate Reframing: From Abuse to “Controversy”

Unlike Kristin Cabot and Paige Shiver, Lieutenant Quathisha Epps’ allegations were not framed as either a human-cost narrative or a resolved power-imbalance failure. They were framed, from inception, as a credibility dispute requiring public skepticism.

That distinction is critical.

Cabot’s case—where no sexual relationship was admitted and no coercion alleged—was framed as a story about humiliation, internet cruelty, and the psychological toll of viral exposure. The inquiry centered on harm suffered, not truthfulness.

Shiver’s case—where an intimate relationship between a supervisor and subordinate was acknowledged—was framed as an institutional violation resolved through policy. Responsibility was assigned upward. The subordinate’s credibility was not publicly litigated.

Epps’ case followed neither path.

Instead of beginning with the nature of the power imbalance between the Chief of Department and a lieutenant, the framing immediately shifted to whether Epps herself was believable. The allegations were treated not as presumptively serious claims requiring protection, but as assertions that needed to be tested against collateral narratives.

This reframing did not occur after investigation.

It occurred before one.

And once that frame was set, every subsequent response—media, institutional, and investigative—operated within it.

C. Media Framing: Severity Without Presumption

The reporting on Epps is striking for its contradiction.

On the one hand, media outlets—including the New York Post—published graphic descriptions of alleged sexual conduct. The allegations were detailed, disturbing, and explicit. They left little doubt as to their seriousness.

On the other hand, the framing never permitted the reader to settle into belief.

Credibility qualifiers saturated the coverage:

“alleged”

“claims”

“denies”

“convenient timing”

“caught stealing time”

These phrases were not merely balance. They were narrative anchors. They instructed the audience how to read the allegations: cautiously, skeptically, conditionally.

This is not how Kristin Cabot was framed.

It is not how Paige Shiver was framed.

Severity did not produce belief.

It produced hesitation.

D. The Overtime Pivot

Almost immediately, coverage of Epps’ allegations became entangled with her overtime earnings. This was not incidental. It was structural.

Overtime did not contextualize the allegations; it competed with them. The story became bifurcated:

Was this about sexual coercion by the Chief of Department?

Or was this about a lieutenant who “made too much money”?

That false equivalence served a function. It recast power as suspect and shifted institutional scrutiny away from the alleged abuser and onto the complainant.

No similar pivot occurred in Cabot’s case.

No such pivot was institutionally sanctioned in Shiver’s case.

This is the moment where credibility ceased to be presumed and began to be litigated in public.

E. Institutional Posture: Defense Before Inquiry

The NYPD’s posture from the outset was not protective. It was defensive.

There was no public articulation of safeguarding obligations. No acknowledgment of the inherent power imbalance between the Chief of Department and a lieutenant subordinate. No language of insulation or non-retaliation.

Instead, the institution moved quickly to frame the matter as contested, complex, and entangled with unrelated issues—exactly the posture that maximizes institutional discretion and minimizes accountability.

This is not an accident. It is a known strategy in high-stakes organizational crises: delay moral clarity by multiplying procedural questions.

F. Credibility as a Racialized Threshold

The most consequential aspect of this framing is not gendered alone. It is racialized.

Black women who accuse powerful men of sexual abuse are rarely permitted to occupy the status of “credible complainant” without first clearing an evidentiary and moral gauntlet. Their allegations may be aired, but belief is withheld.

Epps was required—immediately—to survive scrutiny that neither Cabot nor Shiver faced:

Scrutiny of finances

Scrutiny of timing

Scrutiny of motive

Scrutiny of professionalism

This is the credibility tax imposed on women of color within hierarchical institutions. It is not written into law, but it is enforced through practice.

G. The Structural Consequence

Once credibility is framed as unresolved, everything that follows becomes permissible.

Investigations multiply.

Discipline can be justified as “neutral.”

Isolation can be framed as “process.”

Retaliation can be laundered as compliance.

This is why the opening frame matters more than any later finding.

By the time formal proceedings begin, the outcome has already been shaped—not by evidence, but by who the institution decided to protect.

V. Retaliation by Procedure: How Institutions Punish Credible Threats Without Saying So

Retaliation, as courts increasingly recognize, is rarely blunt. In modern institutions—particularly paramilitary ones like the NYPD—it is administrative, procedural, and cumulative. It does not announce itself as punishment. It presents as process.

What followed Lieutenant Quathisha Epps’ filing was not a single adverse act. It was a sequence of institutional decisions, each defensible in isolation, but together unmistakable in purpose and effect: to neutralize the complainant, reframe the narrative, and reassert control.

What makes this sequence legally and morally significant is not merely that it occurred—but that it did not occur for Kristin Cabot or Paige Shiver.

This is not conjecture. It is pattern.

A. Immediate Suspension: Signaling Isolation, Not Neutrality

Shortly after her allegations against Chief of Department Jeffrey B. Maddrey became public, Lieutenant Quathisha Epps was suspended.

Suspension is often described as a neutral administrative step—an effort to “stabilize” an organization while allegations are reviewed. In practice, particularly in paramilitary institutions, it operates very differently. Suspension severs institutional affiliation, strips authority, and sends a clear message to colleagues and subordinates that the complainant is a problem to be contained. It is reputational quarantine masquerading as process.

The timing here is dispositive. Epps was suspended after engaging in protected activity, and after the accused had already resigned. The Department was no longer managing an active power imbalance between supervisor and subordinate. Yet the first visible act of institutional control was directed not at the alleged abuser, but at the accuser.

That choice matters.

In the public record surrounding Kristin Cabot and Paige Shiver, there is no indication that either woman was immediately removed from the workplace as an institutional response to her allegations. There is no reporting that either was suspended as a preliminary measure, publicly isolated to signal distrust, or administratively sidelined in the name of organizational stability. Whatever internal steps their employers may have taken, the outward posture was not one of preemptive separation.

That contrast is instructive—not because it proves identical circumstances, but because it highlights discretion.

Suspension is not mandatory. It is a choice. And here, that choice was exercised against the complainant, not the accused, at a moment when the stated rationale of “neutral stabilization” no longer applied.

Legally, suspension following protected activity is a classic adverse action under Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 1983, the New York State Human Rights Law, and the New York City Human Rights Law. Courts do not require a formal finding of guilt to recognize its retaliatory effect. Timing, context, and comparator treatment are enough.

Viewed in that light, the suspension of Lieutenant Epps cannot be understood as routine administration. It functioned as discipline—imposed early, imposed publicly, and imposed selectively.

That is the first procedural signal in a larger pattern.

B. The Overtime Narrative as Retaliatory Reframing

Almost immediately, the Department advanced a new narrative: overtime abuse.

Overtime did not emerge organically as a compliance concern. It emerged as a counterweight to the allegations—an alternative explanation for scrutiny that conveniently reframed the complainant as the problem.

This move matters for two reasons.

First, overtime authorization is not unilateral. It is approved, supervised, and budgeted at higher levels. To retroactively cast overtime as misconduct without addressing systemic approval mechanisms is to weaponize oversight selectively. The decision to elevate overtime into a misconduct narrative—rather than treat it as an internal accounting matter—was a discretionary institutional choice, not a legal necessity.

Second, courts recognize that manufactured performance or compliance critiques following protected activity are among the most common forms of retaliation. They convert whistleblowers into rule-breakers.

No comparable “financial misconduct” narrative was constructed for Cabot or Shiver.

Their earnings were not retroactively scrutinized.

Their compensation was not reframed as suspect.

Their credibility was not attacked through accounting.

The overtime allegations served exactly that function—transforming a complainant into a compliance problem in a way that neither Cabot nor Shiver experienced.

In the publicly reported treatment of Kristin Cabot and Paige Shiver, no comparable compliance-based counter-narrative emerged to reframe their allegations. There was no parallel effort to recast either woman as a rule-breaker, financial opportunist, or administrative problem as a response to coming forward. Whatever internal reviews may have occurred, the public-facing narrative remained focused on the conduct of others—not on alleged improprieties by the complainants themselves.

No analogous financial narrative was constructed contemporaneously—or retroactively—against Cabot or Shiver, reinforcing that this reframing was reactive, not routine.

C. Internal Investigations as Pressure, Not Fact-Finding

Following the complaint, internal NYPD investigations proliferated.

Again, investigations are often defended as neutral. But retaliation doctrine does not ask whether investigations are permitted; it asks whether they are weaponized.

Multiple investigations—particularly when overlapping, publicized, and prolonged—operate as pressure. They consume time, resources, and emotional capacity. They also create a steady stream of negative information that feeds media narratives.

In the publicly reported handling of Kristin Cabot and Paige Shiver, there is no indication that either woman was subjected to cascading, parallel internal investigations directed at them personally after coming forward. Whatever internal reviews may have occurred, the institutional response did not manifest as a multi-track investigative posture aimed at the complainant herself.

Here, investigation did not narrow the dispute. It widened it.

That is not how good-faith fact-finding operates. It is how institutions deter.

D. Federal Scrutiny Redirected Toward the Complainant

The escalation did not stop internally. Federal scrutiny entered the picture—but not solely as oversight of alleged abuse by a senior official.

Instead, scrutiny expanded to encompass Epps herself.

This inversion is critical. Federal involvement is often cited as evidence of seriousness. But seriousness directed at the complainant is not accountability; it is chilling.

In the publicly reported handling of Kristin Cabot and Paige Shiver, federal scrutiny—where it existed—remained external and contextual. Neither woman was publicly framed as the subject of federal concern, nor was federal attention used to cast suspicion on her credibility or suggest personal criminal exposure.

By contrast, in Epps’s case, the existence of federal interest was redirected inward—toward the complainant herself—through insinuation, narrative inversion, and reputational framing.

Retaliation law is explicit: actions that would deter a reasonable person from reporting discrimination are unlawful, regardless of whether they appear procedurally legitimate. Federal attention aimed at the whistleblower accomplishes precisely that deterrent effect.

E. Not Fraud, But Failure: How “Payroll Compliance” Becomes Retaliation by Procedure Under Federal and State Labor Law

In a functioning institution, payroll compliance is boring. It is accounting, not character. It is a question of recordkeeping, not morality. But in a defensive institution—particularly a paramilitary one—payroll becomes something else entirely: a procedural instrument used to reframe a complainant as a suspect and to convert protected activity into alleged misconduct.

That is exactly the maneuver that followed Lieutenant Quathisha Epps’s allegations against former Chief of Department Jeffrey B. Maddrey.

In the publicly documented handling of Kristin Cabot and Paige Shiver, payroll compliance did not become a character narrative. Neither woman was publicly reframed as financially suspect, nor subjected to clawbacks, payroll audits cast as misconduct, or insinuations of criminality tied to compensation.

The NYPD did not respond to Epps’ protected disclosures by stabilizing the workplace, insulating the complainant, and investigating the alleged abuse of power. Instead, it escalated a counter-narrative—“overtime abuse”—and then dressed that narrative in the language of neutral enforcement: audits, missing slips, reconstructed records, clawbacks, and referrals.

This is retaliation by procedure. And the law that governs it—federal wage-and-hour law—does not support the NYPD’s theory. It defeats it.

1. Federal Law Controls First: The FLSA Places Recordkeeping Responsibility on the Employer

The Fair Labor Standards Act governs first. 29 U.S.C. § 211(c) and the implementing regulations in 29 C.F.R. Part 516 impose a nondelegable duty on employers to “make, keep, and preserve” accurate records of hours worked and wages paid. The statute assigns that burden to the employer for a reason: employers control the system. Employees do not.

The consequence of employer recordkeeping failure is not a gray area. The Supreme Court resolved it in Anderson v. Mt. Clemens Pottery Co., 328 U.S. 680 (1946). Where an employer’s records are inadequate or nonexistent, the employee may prove hours worked through evidence sufficient to permit a “just and reasonable inference”—including estimates, testimony, reconstructed logs, calendars, and indirect proof. Once the employee makes that showing, the burden shifts to the employer to produce precise records to rebut it. If the employer cannot, the employee’s approximation controls.

This doctrine is remedial by design. The Supreme Court’s point was not subtle: an employer cannot benefit from the uncertainty created by its own recordkeeping failure.

So when an institution like the NYPD begins implying that reconstruction equals deception, it is not applying the law. It is inverting it.

2. New York Law Confirms the Same Rule—It Does Not Alter It

New York law follows the same framework. Labor Law § 195(4) and 12 NYCRR § 142-2.6 require employers to preserve payroll records for at least six years. New York courts adopt the federal burden-shifting principle: when an employer fails to maintain adequate records, the resulting inexactitude is charged to the employer, not weaponized against the worker.

In Matter of Mid Hudson Pam Corp. v. Hartnett, 156 A.D.2d 818 (3d Dep’t 1989), the Appellate Division held that where the employer failed to keep adequate records, “any inexactitude in the computation of wages due should be resolved against the employer whose failure to keep adequate records made the problem possible.”

That line matters here because it clarifies what reconstructed records mean in law: they do not create a presumption of fraud. They create a presumption of employer noncompliance.

3. Applied to Epps: “Missing Slips” Are Not Proof of Misconduct—They Are Proof of System Control

This is where Section IV’s procedural-retaliation framework becomes concrete.

Lieutenant Epps was not a private employee free-lancing her own hours. She was a lieutenant in a command-driven institution where overtime is:

authorized through supervisory structures,

budgeted through command decisions,

submitted and coded through payroll personnel,

and paid only after approval by the employer.

If the NYPD’s recordkeeping in that environment produced missing slips, replaced forms, or reconstructed entries, those irregularities do not establish employee fraud. Under the FLSA and NYLL, they establish institutional responsibility—because the institution controls the recordkeeping architecture and bears the legal duty to preserve it.

That is why this is retaliation by procedure: it uses the employer’s own recordkeeping failures as the predicate for punitive action against the complainant.

4. Fraud Requires Intent; Reconstruction Is Often the Legally Anticipated Substitute

The most revealing feature of this tactic is linguistic. “Fraud” is not an audit term; it is an accusation term. It is designed to trigger moral judgment and criminal suspicion.

But under wage-and-hour doctrine, reconstruction is not synonymous with falsification. Reconstruction is the legally anticipated substitute when the employer cannot produce reliable primary records. Fraud, by contrast, requires scienter—knowing falsification with intent to deceive for unlawful gain.

Courts applying Anderson do not demand perfect records from employees; they demand good-faith approximation when the employer’s records fail. The NYPD’s attempt to treat imperfection as intent is not a legal argument. It is a credibility attack wearing the costume of compliance.

And in the retaliation context, that matters because credibility attacks are often the real objective.

5. Supervisory Direction and Institutional Custom Cannot Be Retroactively Criminalized

This point is particularly important in paramilitary workplaces. Employees follow orders. Payroll systems are not negotiated; they are imposed. Where supervisors or payroll staff instruct employees to recreate documentation, submit time retroactively, or rely on manual processes in lieu of electronic systems, subordinates do not thereby become fraudsters. They become witnesses to a system’s informal customs.

An institution cannot normalize a workaround for months or years and then—once a complainant engages in protected activity—declare the workaround fraudulent. That is not enforcement. It is selective enforcement.

And selective enforcement is one of the clearest procedural signatures of retaliation because it is the mechanism by which an institution punishes without admitting it is punishing.

6. The Section IV Point: The Payroll Narrative Functions as a Second, Parallel Prosecution

Within Section IV’s architecture, the payroll tactic functions as a parallel case built against the complainant.

The institution does not need to disprove the harassment allegations. It only needs to make the complainant untrustworthy in public view—so that every allegation becomes “a convenient time,” every disclosure becomes “a distraction,” and every act of courage becomes “motive.”

That is why the payroll framing is so powerful as retaliation-by-procedure: it converts a woman alleging abuse of power into an alleged abuser of funds. And in a public-facing agency, “taxpayer money” is the most effective moral cudgel available.

7. If the NYPD Wants to Argue Fraud, It Must First Explain Its Own Records

Under the FLSA, recordkeeping is not optional, and gaps do not authorize a presumption of guilt. Under New York law, any uncertainty created by inadequate records is charged to the employer.

So when reconstructed payroll records are treated as “fraud” in the wake of protected activity, the issue is no longer payroll. It is retaliation—disguised as accounting.

And that is the throughline of Section IV: the institution does not have to announce punishment. It only has to convert process into pressure, and paperwork into condemnation.

F. Professional Erasure After Separation: Denial of Credentials, Certification, and Lawful Carry

Following her retirement, Lieutenant Epps was denied a Good Guy Letter and a retired identification card. Standing alone, those denials might be dismissed as discretionary slights. In context, they were something far more consequential: the opening moves in a coordinated effort to sever her professional legitimacy and foreclose her future.

In contrast, neither Kristin Cabot nor Paige Shiver experienced post-separation institutional erasure. In their cases, separation did not trigger credential invalidation, regulatory referral, or administrative steps designed to foreclose future employment.

In law enforcement culture, a Good Guy Letter and retired ID are not ceremonial. They function as institutional attestations of service, integrity, and separation without dishonor. They determine whether a retired officer may credibly seek post-separation employment, consultative work, or law-enforcement-adjacent roles. Withholding them communicates condemnation without adjudication—punishment without process.

Critically, these denials occurred in the absence of any sustained disciplinary finding, trial, or formal adjudication of misconduct. They were not mandatory. They were discretionary. And discretion is where retaliation most often hides.

But the retaliation did not end with symbolic exclusion.

The NYPD went further. It transmitted formal notice to the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services (DCJS)—the agency responsible for Police Officer Standards and Training (POST)—resulting in the revocation of Lieutenant Epps’s POST certification. This action carried profound and irreversible consequences. POST certification is not merely a credential; it is—as a practical and legal matter—the professional license that determines whether a former officer may lawfully work in law enforcement and, as a practical matter, whether she may pursue post-separation employment in security, investigations, compliance, training, or related fields. Revocation does not place a career in jeopardy—it extinguishes it.

This maneuver matters for several reasons.

First, it extended the Department’s control beyond separation. Retirement is supposed to mark the end of institutional authority. By invoking DCJS, the NYPD ensured that Epps would remain under professional restraint long after she left its payroll.

Second, it transformed unproven allegations and administrative disputes into de facto disqualifications. No hearing preceded the notice. No sustained finding justified it. The mere existence of controversy—manufactured through prior investigative and media pressure—was leveraged into credential jeopardy.

Third, it directly impacted her eligibility under H.R. 218 (LEOSA), the federal statute that permits qualified retired law enforcement officers to carry firearms nationwide. LEOSA eligibility hinges on good standing at separation and possession of qualifying identification. By denying retired ID and triggering credential scrutiny, the Department materially interfered with her ability to exercise a federally protected right.

This is not incidental. Lawful carry under LEOSA is not a perk; it is a safety and professional necessity for many former officers. Denying it increases vulnerability while signaling to future employers that the individual is “problematic,” regardless of the absence of adjudicated wrongdoing.

Taken together, these actions amount to professional erasure by administrative means. The institution did not need to terminate Lieutenant Epps again. It did not need to issue a formal finding. It simply needed to deny credentials, alert regulators, and allow the consequences to cascade.

This is retaliation refined.

Courts recognize that adverse action is not limited to termination or demotion. Any action that would dissuade a reasonable person from engaging in protected activity—including actions that impair future employment, licensure, or professional standing—falls squarely within retaliation doctrine. Credential interference, certification threats, and licensing consequences are among the most potent forms of post-employment retaliation precisely because they are difficult to unwind and devastating in effect.

The message communicated here was unmistakable: speaking up would not merely cost Lieutenant Epps her position. It would cost her career, her credentials, and her autonomy—even after she left.

That is not neutral administration.

It is institutional punishment by procedure.

G. Media Reinforcement and Pleading Abuse: How Retaliation Migrates From the Press to the Courtroom

Retaliation in modern institutional cases does not operate on a single track. It moves laterally—between media, internal process, and litigation—each reinforcing the other. In Lieutenant Epps’s case, the New York Post’s repetitive focus on overtime and alleged improprieties did not exist in isolation. It was mirrored, amplified, and legitimized through the misuse of civil pleadings as narrative weapons.

The New York Post published repeated stories centered not on former Chief of Department Jeffrey B. Maddrey’s alleged conduct, but on Epps’s overtime, earnings, and purported misconduct. The repetition mattered. Retaliation does not require direct authorship of media coverage; it requires facilitation, leakage, and tolerance. When an institution allows a single discrediting narrative to dominate public discourse, the cumulative effect is to reframe the complainant as suspect and the allegations as diversionary.

In Cabot’s case, media emphasis remained on reputational harm, privacy, and proportionality. In Shiver’s case, coverage centered institutional policy, power imbalance, and supervisory responsibility. In Epps’s case, coverage fixated on character, credibility, and alleged impropriety—substituting personal suspicion for structural analysis.

What distinguishes this case is that the same narrative migration occurred inside court filings.

In Thomas G. Donlon v. City of New York, Index No. 25-cv-5831 (S.D.N.Y. 2025), attorney John Scola escalated this tactic beyond insinuation into outright fabrication. In Paragraph 1263 of the Federal Complaint, Scola alleged that the Federal Bureau of Investigation conducted a raid on the home of Lieutenant Quathisha Epps—an event that never occurred. There was no factual basis, no corroboration, and no legitimate litigation purpose for the claim. Its function was obvious: to portray a Black female whistleblower as the subject of a criminal investigation and thereby collapse her credibility in the public imagination.

The falsity of the allegation is not incidental. Scola was fully aware that federal scrutiny existed not because of Epps, but because of Epps’s own complaints—complaints alleging quid pro quo sexual harassment, coercion, and conduct amounting to a criminal sexual act under New York Penal Law §§ 130.05 and 130.50, actionable under the Gender-Motivated Violence Act, and implicating broader patterns of public corruption within the NYPD. That investigation, now understood to extend beyond Maddrey to executive commands, the Aviation Unit, and City Hall, was inverted through pleading into a narrative of Epps as target rather than catalyst.

By inserting a fabricated FBI raid into a federal complaint, Scola attempted to reverse victim and perpetrator, poison the judicial record, and chill other officers from coming forward. This was not zealous advocacy. It was retaliatory storytelling dressed as pleading.

The same pattern reappeared in Jamie Nardini v. City of New York, Index No. 161972/2025 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Cnty. 2025). There, Scola again relied on salacious, irrelevant, and demonstrably false narrative devices to smear Lieutenant Epps. Within the Verified Complaint, he gratuitously alleged that Epps was the “girlfriend” of Assistant Chief Ruel Stephenson, a Black male executive—an assertion wholly immaterial to any claim or defense and plainly prohibited by CPLR 3024(b), which bars scandalous or prejudicial matter unnecessary to the litigation.

These allegations served no lawful purpose. They were not probative. They were not relevant. They were designed to taint the record, racialize suspicion, undermine Epps’s pending sexual-harassment claims, and signal to other officers—particularly officers of color—that reporting misconduct would invite personal destruction.

This is how retaliation modernizes. Media repetition supplies the backdrop. Civil pleadings provide the imprimatur of legitimacy. Together, they transform accusation into atmosphere.

Retaliation doctrine does not require proof that the employer authored every headline or drafted every paragraph. It asks whether institutional actors tolerated, facilitated, or benefited from a campaign that would deter a reasonable person from engaging in protected activity. Here, the answer is unmistakable. The same overtime narrative migrated from press to pleading. The same credibility attack reappeared under oath. The same objective persisted: to make Lieutenant Epps radioactive.

The public learns what to think by what is repeated. Courts learn what to assume by what is pled. When false narratives are allowed to travel uncorrected across both domains, retaliation no longer looks like punishment.

It looks like process.

H. The Legal Bottom Line

Viewed individually, each of these actions can be rationalized.

Viewed together, they cannot.

That conclusion is underscored by comparison: neither Kristin Cabot nor Paige Shiver was subjected to cascading discipline, investigative saturation, credential destruction, or narrative criminalization after reporting—or being associated with—workplace misconduct.

Retaliation doctrine does not require a smoking gun. It requires a pattern that would deter a reasonable person from engaging in protected activity. Suspension, investigation, financial punishment, reputational attack, and post-retirement exclusion meet that standard decisively.

This is not institutional confusion.

It is institutional self-preservation.

And it explains why credibility was never allowed to settle in the first place.

With that procedural pattern established, the remaining question is what it reveals about credibility itself—and what the law actually requires institutions to do once a report is made.

VI. Credibility as an Institutional Decision — Not a Fact-Finding Outcome

By the time a sexual-harassment case reaches a courtroom, credibility is often treated as a question of proof. But as the preceding sections demonstrate, credibility is rarely adjudicated first. It is assigned first.

Institutions do not wait for findings to decide how seriously an allegation will be treated. They decide—often immediately—whether the allegation represents a threat to institutional stability or a problem that can be contained without cost. That decision determines the trajectory of the case long before evidence is weighed.

This is the structural failure point of modern civil-rights enforcement: credibility functions as a gatekeeping mechanism, not as a conclusion.

Once credibility is conferred, institutions narrow their response. Once credibility is withheld, institutions expand it.

A. Credibility Determines Institutional Posture

The law presumes neutrality. Institutions do not.

At the moment an allegation becomes public or formally lodged, an institution makes a strategic assessment:

Does this allegation expose the organization itself?

Does it implicate senior leadership?

Does it threaten reputational capital, budgetary authority, or political alliances?

If the answer is no, the institution can afford to believe.

If the answer is yes, belief becomes dangerous.

Credibility, in that context, is no longer a moral judgment. It is a risk calculation.

B. Retaliation Is the Downstream Effect of Withheld Credibility

Retaliation doctrine often focuses on discrete acts: suspension, investigation, discipline, termination. But those acts are not the cause. They are the consequence.

What precedes retaliation is the institutional refusal to settle on belief.

When credibility is treated as unresolved, every protective norm dissolves. Suspension becomes “neutral.” Audits become “compliance.” Investigations multiply under the guise of diligence. Media narratives are tolerated—or quietly reinforced—because uncertainty is institutionally useful.

This is why retaliation today rarely announces itself. It masquerades as process.

C. Why Race Matters at the Credibility Stage

Race does not merely affect how allegations are received. It affects how much institutional risk an allegation is perceived to carry.

When a complainant is Black—particularly when she accuses a powerful white or institutionally protected actor—the allegation is more likely to be framed as destabilizing. The institution anticipates scrutiny not only of conduct, but of structure. Credibility, therefore, becomes something to be managed rather than granted.

This is not implicit bias alone. It is organizational self-preservation operating through racialized assumptions about trustworthiness, motive, and resilience.

The result is predictable: belief is deferred, scrutiny intensifies, and the complainant is forced to survive the process in order to earn legitimacy.

D. Media as a Credibility Multiplier — Not an Independent Actor

Media coverage does not create institutional response, but it locks it in.

Once an institution has chosen to treat credibility as unresolved, media narratives that emphasize doubt, timing, money, or character become useful. They justify continued investigation. They rationalize delay. They normalize skepticism.

This is why credibility attacks migrate so easily between press coverage and legal pleadings. Both serve the same function: preserving institutional discretion by preventing narrative closure.

E. The Core Legal Failure

Civil-rights law is built on the premise that reporting misconduct should not expose the reporter to harm. That premise collapses if credibility must be earned through endurance.

When belief is conditional, retaliation does not need to be explicit. The process itself becomes punitive. The law’s promise—to protect those who report abuse of power—fails not because standards are unclear, but because institutions decide whom they are willing to believe before the law ever speaks.

F. The Throughline

The cases discussed in this commentary do not reveal inconsistent enforcement. They reveal consistent incentives.

Institutions believe when belief is cheap.

They doubt when belief is costly.

And they retaliate—procedurally—when doubt preserves power.

That is not a failure of individual actors.

It is a structural feature of how credibility is allocated in systems built to protect themselves.

VII. What the Law Requires — and What Institutions Choose Instead

The preceding sections establish a difficult but unavoidable conclusion: the failure exposed here is not evidentiary. It is institutional.

Sexual-harassment law does not collapse because standards are unclear or because power dynamics are hard to identify. It collapses because institutions make an early, consequential choice about credibility—one that determines whether the law will ever meaningfully engage.

This choice is not compelled by statute. It is not required by doctrine. It is not inevitable.

It is strategic.

A. The Law’s Command Is Clear

Federal, state, and local civil-rights regimes are explicit about three principles that govern sexual-harassment enforcement.

First, power distorts consent. Title VII, § 1983, the NYSHRL, and the NYCHRL all recognize that supervisor–subordinate relationships are inherently coercive, and that formal authority—over pay, assignments, promotion, discipline, or professional survival—renders “consent” legally suspect.

Second, protected activity must be insulated. Once an employee reports sexual harassment, the employer’s obligation is not merely to investigate the allegation, but to protect the reporting individual from adverse action, isolation, reputational harm, and professional sabotage—both during and after the process.

Third, retaliation doctrine is functional, not formal. Courts do not ask whether an institution labeled its actions “discipline” or “process.” They ask whether the employer’s conduct, viewed cumulatively, would deter a reasonable person from reporting misconduct.

These are not aspirational principles. They are settled law.

B. Where Institutions Deviate

The cases examined here show how institutions depart from those principles—not overtly, but procedurally.

Rather than begin with protection, institutions begin with risk assessment.

Rather than interrogate power, they interrogate credibility.

Rather than contain harm, they expand process.

This inversion produces a predictable pattern:

Credibility is treated as unresolved.

Neutrality is invoked to justify delay.

Process becomes pressure.

And retaliation is laundered through compliance.

None of this requires bad faith in the conventional sense. It requires only an institutional belief that believing the complainant would be more dangerous than doubting her.

C. Why Comparison Matters

Comparative analysis is not rhetorical flourish. It is legal proof.

The differential treatment of Kristin Cabot, Paige Shiver, and Lieutenant Quathisha Epps demonstrates that institutional response is not driven by the severity of allegations, the clarity of power imbalance, or the availability of policy frameworks. It is driven by who poses a threat to institutional equilibrium.

When belief stabilizes the organization, it is granted.

When belief destabilizes it, skepticism follows.

This is not inconsistency.

It is calibration.

D. The Cost of Conditional Belief

The greatest harm revealed by this pattern is not reputational. It is deterrent.

When institutions require complainants—particularly Black women accusing powerful officials—to endure suspension, investigation, audit, media scrutiny, and professional erasure before being deemed credible, they redefine the price of reporting.

The message becomes unmistakable:

You may report.

But you must survive the response.

That message violates the core promise of civil-rights law. And it explains why underreporting persists—not because misconduct is rare, but because retaliation is predictable.

E. What Accountability Would Actually Look Like

Meaningful compliance does not require perfection. It requires sequence.

Institutions that act lawfully do three things, in order:

They presume seriousness, not deceit.

They assign responsibility upward, not outward.

They insulate the complainant, not the organization.

This does not predetermine outcomes. It preserves legitimacy.

Where institutions instead suspend complainants, escalate collateral narratives, weaponize payroll or compliance mechanisms, tolerate credibility attacks, and interfere with post-employment standing, they are not enforcing the law. They are defending themselves.

F. The Final Point

The question this commentary poses is not who is telling the truth.

It is who is allowed to be believed long enough for the truth to matter.

Until institutions confront the reality that credibility is being allocated—not discovered—sexual-harassment law will continue to fail at the gate. And those failures will continue to fall hardest on those whose allegations threaten power most directly.

The law already knows what to do.

The remaining question is whether institutions are willing to do it.