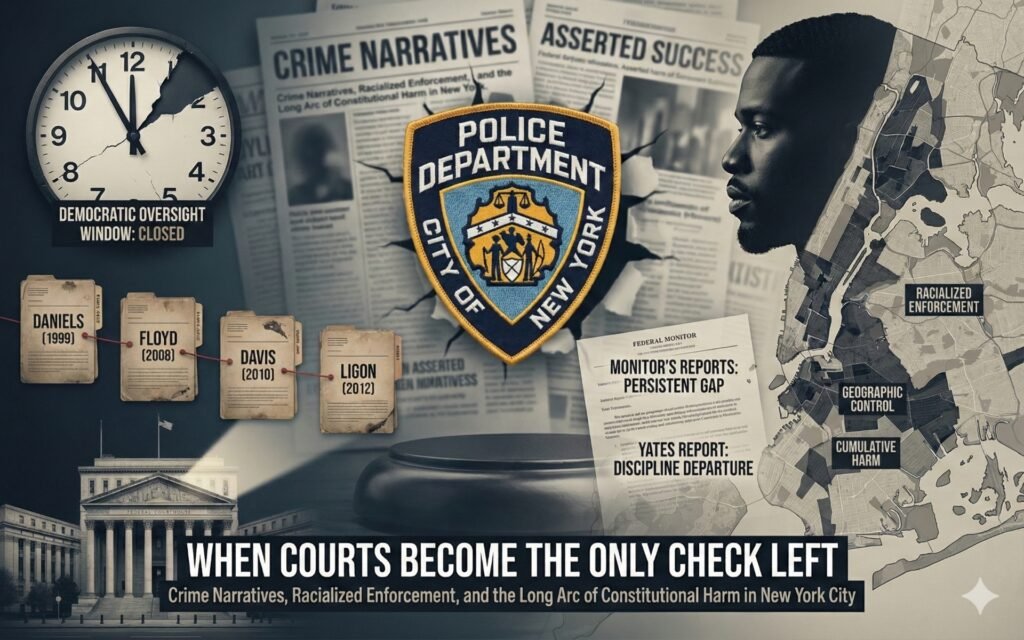

Crime Narratives, Racialized Enforcement, and the Long Arc of Constitutional Harm in New York City

From Daniels, Floyd, Davis, and Ligon — and why Black New Yorkers paid the price of delayed oversight

Executive Summary

Crime narratives do not merely describe public safety. They authorize power. They determine when enforcement may expand, when scrutiny is postponed, and when accountability is treated as unnecessary. In New York City, for decades, those narratives asserted success with a confidence that outran proof—closing democratic windows long before courts were forced to intervene.

This analysis begins from a simple but consequential premise: oversight has a window. Democratic accountability is not an abstract ideal; it is a time-sensitive process. It must occur before enforcement strategies harden into doctrine, before budgets lock in assumptions, before metrics are normalized as truth, and before entire neighborhoods are transformed into sites of presumed suspicion. When that window closes, later transparency cannot restore what was lost. At best, it can document damage after the fact.

For years, New York City was told a story of crime control success—repeated by the Police Department and amplified by legacy media as settled fact. That story relied on correlation presented as causation, on aggregate trends substituted for attribution, and on selective metrics treated as proof rather than description. Methodological limits were not merely underexplained; they were rendered irrelevant by repetition. Once success was asserted with sufficient confidence, scrutiny became unnecessary. Skepticism was reframed as indifference to safety. Oversight was deferred in the name of progress.

This piece asks what happened during that period of asserted certainty—before courts intervened, after warnings were issued, and while enforcement expanded without proof.

The answer is not theoretical. It is documented in a long judicial record of systemic constitutional violations, disproportionately borne by Black New Yorkers—particularly Black men. Those findings did not emerge because harm was hidden. They emerged because harm was endured long enough, normalized deeply enough, and insulated thoroughly enough that judicial intervention became the only remaining check.

That record begins earlier, with Daniels v. City of New York (1999), which challenged the Street Crimes Unit’s practices as racially discriminatory and unconstitutional. Daniels ended not with a merits verdict but with a court-approved settlement requiring policy changes, audits, training, and periodic reporting—an institutional chance to correct course while oversight still had time to function. The fact that later litigation was necessary is the point: the logic survived the paperwork.

The later cases—Floyd v. City of New York, Ligon v. City of New York, and Davis v. City of New York—are not discrete episodes or historical anomalies. Read together, they form a chronological record of delayed accountability. Each represents a moment when courts were compelled to step into a space where democratic oversight should have acted earlier and more forcefully. Each reflects not the sudden discovery of misconduct, but the judicial confirmation of patterns that had already been lived, protested, and ignored.

In Floyd, the court found that stop-and-frisk practices violated the Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments through widespread, racially discriminatory enforcement. Floyd is a liability decision reached after discovery and a lengthy bench trial, followed by a remedial order. The point is not that courts “disagreed” with policing strategy—the point is that the record compelled constitutional findings, and the remedy required ongoing institutional supervision precisely because internal controls were insufficient. Black and Latino men were subjected to suspicion at scale—not because of individualized conduct, but because crime narratives had transformed racial presence into proxy for criminality. The constitutional injury did not lie solely in unlawful stops. It lay in the normalization of suspicion applied repeatedly to the same communities under the banner of public safety success.

Ligon extended that logic spatially. Ligon challenged the City’s private-building trespass regime under Operation Clean Halls / the Trespass Affidavit Program and produced injunctive relief based on a documented pattern of unlawful stops in that context. Its significance here is architectural: it shows how “place” became a standing proxy for suspicion, expanding the footprint of intrusion while the City continued to rely on broad safety narratives rather than proof tethered to individualized conduct. Trespass enforcement became a mechanism of geographic control, particularly in and around residential buildings disproportionately occupied by Black New Yorkers. Presence itself was treated as suspect. Aggregated crime narratives masked neighborhood-level disparities, depriving residents of the ability to contest enforcement that functioned less as response to conduct than as presumption of illegitimacy.

Davis demonstrated what happens when institutional learning fails. Davis arose in a distinct enforcement setting—NYCHA buildings—where vertical patrols and trespass arrests produced a separate evidentiary record and separate settlement obligations. It belongs in this chronology not as a duplicate of Floyd, but as proof that the same discretionary logic reappeared in spaces with even less visibility, and therefore even weaker real-time accountability. Even after judicial rebuke, the underlying logic persisted. Enforcement rationales adapted in form but not in substance. Vocabulary shifted. Metrics were reconfigured. But the narrative architecture remained intact. The same communities continued to bear the weight of strategies justified by asserted effectiveness rather than demonstrated causation.

Together, these cases reveal a pattern that cannot be dismissed as coincidence or isolated misconduct. They show how crime narratives, once accepted as truth, foreclose oversight by converting questions into inconveniences and objections into threats. They show how democratic mechanisms—budget hearings, policy debates, legislative inquiry—were narrowed, redirected, or deferred while enforcement expanded. And they show why courts, by design reactive and limited, were ultimately forced to intervene only after harm had already accumulated.

But the record does not end with liability findings.

Post-liability monitoring and discipline reviews—reflected in the federal Monitor’s recent reporting and the Yates discipline analysis—show a persistent gap between rule-writing and consequence. The recurring failure mode is not ignorance of constitutional standards; it is implementation: unlawful or unsupported encounters identified through audits and review mechanisms do not reliably translate into supervisory correction or meaningful discipline. In other words, visibility has improved, but deterrence remains structurally weak—allowing the institution to “comply” on paper while preserving discretionary practices where harm concentrates.

This post-liability record matters because it dispels any lingering illusion of redemption through disclosure alone. Transparency initiatives are necessary. They are also insufficient. Disclosure can illuminate patterns going forward, but it cannot retroactively reopen democratic windows closed by assertion and repetition. Budgets were adopted. Strategies were expanded. Careers were shaped. Trust was eroded. Those moments cannot be replayed simply because data is now visible.

For the communities on the receiving end, the cost of delayed oversight was paid in units that never appear on dashboards: hours taken by repeated stops, job opportunities lost after arrests that never led to prosecution, housing instability triggered by trespass enforcement, and the cumulative humiliation of being treated as presumptively suspicious in one’s own neighborhood. The point is not sentiment. It is governance: when intrusion is normalized for years before it is tested, the damage becomes irreversible long before the City concedes the methodology.

The racial dimension of this history is not incidental. When enforcement expands without proof, it does not distribute evenly. It concentrates where political resistance is weakest, where visibility is lowest, and where aggregated data most easily erases lived experience. Black New Yorkers—particularly Black men—became the predictable subjects of suspicion, stop discretion, geographic control, and metric-driven enforcement. The resulting constitutional violations were not aberrations. They were the foreseeable outcome of governance by narrative rather than evidence.

This analysis is not an argument against policing or public safety. It is an argument about timing, power, and legitimacy. Courts are not governance mechanisms; they are last resorts. When they become the primary forum for addressing systemic policing practices, it is not evidence of a healthy accountability system. It is evidence that democratic oversight arrived too late.

What follows traces that record chronologically and analytically, without rhetorical excess. It begins before the courts spoke, examines what they were forced to address, and concludes with what accountability would have required—in time.

The measure of legitimacy going forward will not be how persuasively institutions tell their story, but whether they resist the temptation to tell it before it can be proven.

I. Oversight Has a Window

Oversight is not an abstract principle. It is a time-bound function of democratic governance. It must occur while policy choices are still fluid, before authority hardens into routine, and before narratives of success become self-sealing. When oversight is delayed—when it arrives only after strategies have expanded, budgets have been adopted, and metrics have normalized—it loses its corrective force. At that point, accountability can document harm, but it cannot prevent it.

This distinction is essential. Democratic oversight is prospective by design. It is meant to interrogate assumptions before they become commitments and to test justifications before they acquire institutional momentum. Once those moments pass, oversight does not disappear—but it changes character. It becomes reactive, defensive, and constrained by the very decisions it failed to examine in time.

This is the sense in which oversight has a window. It does not remain equally available at all stages of governance. There is a point at which scrutiny ceases to function as a check and instead becomes an after-action report.

In New York City, crime narratives played a decisive role in closing that window. Claims of declining crime, rising clearance rates, and improved public safety outcomes were asserted with a confidence that outran proof. Correlation was treated as causation. Aggregate trends were substituted for attribution. Methodological limits were not merely underexplained; they were rendered irrelevant by repetition. Once success was asserted confidently enough, scrutiny appeared unnecessary. Questions about efficacy, distribution, or disparate impact were reframed as distractions—or worse, as threats to public safety itself.

This is how democratic windows close: not through censorship or conspiracy, but through premature certainty.

When success is treated as settled fact, oversight becomes redundant by definition. Legislative inquiry appears wasteful. Journalistic skepticism is recoded as contrarianism. Community objections are dismissed as anecdotal or ideologically motivated. The burden of proof shifts quietly but decisively—from institutions exercising power to individuals and communities asked to endure it. At that point, accountability does not vanish; it is deferred. It reemerges later, typically in courtrooms, after harm has already accumulated.

That temporal displacement matters because enforcement does not expand in a vacuum. Policing strategies are embedded in annual budget cycles, staffing decisions, performance metrics, and political commitments. Once adopted, those strategies generate their own inertia. Officers are trained to produce certain outputs. Units are structured around specific activity levels. Promotions and evaluations become tethered to metrics that assume the legitimacy of the underlying approach. Data systems are calibrated to reflect activity rather than interrogate purpose.

By the time questions arise about whether the premises were sound, the system has already organized itself around their presumed validity.

At that stage, oversight confronts a fundamentally different challenge. It is no longer asking whether a strategy should be adopted, but whether it should be dismantled. That is a far higher bar—politically, institutionally, and rhetorically. Officials who asserted success cannot easily concede uncertainty without undermining their own authority. Media institutions that amplified those claims face little incentive to revisit them. And communities that experienced harm are told, implicitly, that the moment for objection has passed.

This is not primarily a failure of intent. It is a structural feature of governance by narrative.

Crime data, when treated as proof rather than description, accelerates this process. Aggregated statistics compress complexity, smooth disparities, and reward confident interpretation. They are effective tools of reassurance and poor instruments of accountability. When data is presented without attribution discipline—without sustained attention to causation, context, and distribution—it invites overclaiming. When overclaiming is rewarded with political capital, oversight becomes not merely inconvenient, but destabilizing.

The consequences of delayed oversight are not evenly distributed. Enforcement expanded under asserted certainty does not distribute itself neutrally across a city. It concentrates where discretion is greatest and resistance is weakest. Neighborhoods already subject to heightened police presence absorb additional scrutiny. Individuals already perceived as suspicious encounter it more frequently. The resulting harms—unlawful stops, discriminatory enforcement, erosion of trust—accumulate gradually, often without a single discrete policy decision that can be easily challenged.

This accumulation is critical. Constitutional harm rarely announces itself at inception. It develops through repetition, normalization, and administrative routine. By the time patterns become visible at scale, they are defended not as choices, but as outcomes. What was once discretionary becomes inevitable. What was once contested becomes assumed.

This is why later transparency, however robust, cannot substitute for timely oversight. Disclosure reveals what happened; it does not recreate the conditions under which it could have been prevented. Data released after strategies are entrenched cannot restore the legislative debates that never occurred, the methodological questions that were never asked, or the objections that were dismissed as premature. Oversight that arrives after normalization functions as audit, not governance.

Courts enter this landscape by necessity, not design. Judicial review is reactive by nature. It addresses claims brought after injury has occurred. It is constrained by doctrines of standing, remedy, and deference. When courts intervene in policing practices, they do so because other mechanisms failed to act while action was still possible. Judicial findings of systemic constitutional violations are therefore not evidence of robust accountability; they are evidence that accountability arrived too late.

Understanding oversight as time-sensitive clarifies why the cases examined in this analysis matter beyond their specific holdings. They are not simply adjudications of unlawful conduct. They are institutional signals that democratic mechanisms did not operate when they should have. The injuries they document—disproportionately borne by Black New Yorkers, particularly Black men—were not sudden or unforeseeable. They were the predictable outcome of enforcement strategies expanded under narratives of success that were never rigorously tested.

This section establishes the framework for what follows. The question is not whether oversight eventually occurred. It is whether it occurred before power was exercised at scale. In New York City, the answer is unambiguous. Oversight was deferred while narratives hardened. By the time courts spoke, democratic windows had already closed.

What follows traces that record—beginning before the courts intervened, examining what they were forced to address, and assessing what accountability would have required while it still mattered.

II. Before the Courts Spoke: Warning Signs Ignored

The constitutional violations later addressed by federal courts did not emerge suddenly, nor were they uncovered through novel judicial insight. They accumulated in plain sight. Long before litigation forced institutional reckoning, communities—particularly Black New Yorkers—had been reporting, documenting, and contesting the same patterns of enforcement that courts would eventually find unlawful. What failed was not awareness, but institutional response during the period when oversight could still operate preventively.

This matters because the legitimacy of later intervention turns in part on whether earlier warnings were available and actionable. In New York City, they were. Complaints about discriminatory stops, geographically concentrated enforcement, and routine suspicion directed at Black men were neither rare nor ambiguous. They were persistent, public, and often corroborated by the City’s own data—data that, when aggregated and framed narratively, was used not to interrogate practice but to neutralize criticism.

Community testimony preceded litigation by years. Residents of heavily policed neighborhoods described repeated stops without explanation, questioning untethered to specific conduct, and enforcement that treated presence itself as suspicious. These accounts were not isolated anecdotes; they were patterns described across precincts, housing developments, and transit corridors. Yet they were routinely discounted as subjective, emotional, or politically motivated—insufficiently rigorous to challenge official claims of success.

This asymmetry was structural. Lived experience, particularly when racialized, was required to meet an evidentiary standard that aggregate statistics were never asked to satisfy. Community complaints were expected to prove causation. Official narratives were permitted to assume it.

At the same time, early oversight mechanisms existed but were underutilized or constrained by the same narrative logic. Legislative hearings focused on sustaining progress rather than interrogating attribution. Budget deliberations treated enforcement expansion as self-justifying. Internal audits, where conducted, examined compliance with procedure rather than the validity of underlying premises. External watchdogs raised concerns that were acknowledged rhetorically but rarely translated into structural change.

The problem was not the absence of information. It was the framing of relevance.

Crime data played a central role in this framing. Aggregate reductions in reported crime were presented as evidence of effective policing without sustained analysis of alternative explanations—demographic shifts, economic changes, national trends, or reporting variation. Clearance rates were offered as proof of responsiveness without examination of delay, non-resolution, or neighborhood disparity. Enforcement intensity was conflated with effectiveness, even where outcomes lagged or stagnated.

In this environment, the burden of skepticism was inverted. Those questioning the narrative were required to disprove success, rather than institutions being required to demonstrate causation. Methodological humility was treated as indecision. Requests for disaggregated data were framed as unnecessary or destabilizing. Oversight bodies, rather than insisting on rigor, often accepted reassurance.

This inversion had consequences. Without granular scrutiny, localized failures disappeared into citywide averages. Neighborhoods experiencing persistent non-resolution were statistically absorbed by adjacent areas with better outcomes. Patterns of enforcement concentrated on Black men were rendered administratively invisible through aggregation. The absence of disaggregated reporting did not merely limit public understanding; it constrained the ability of affected communities to articulate claims of unequal treatment in terms institutions were willing to recognize.

Importantly, none of this occurred in a vacuum of protest or silence. Advocacy organizations, community groups, and affected individuals repeatedly raised alarms. They documented stop patterns, geographic concentration, and racial disparity. They filed complaints, testified at hearings, and sought media attention. What they encountered was not outright denial, but institutional deflection—the insistence that the overall picture was positive, that progress should not be undermined by localized concerns, and that existing metrics demonstrated success.

This is how oversight becomes performative rather than corrective. Hearings occur, reports are issued, and commitments are voiced—but the premises driving policy remain unexamined. The window for meaningful intervention narrows not because no one is looking, but because what is seen is filtered through a narrative already declared true.

Race intensified this dynamic. The communities raising concerns were the same communities most affected by enforcement. Their credibility was assessed through a lens shaped by the very narratives they sought to contest. Objections from Black residents were more easily dismissed as oppositional or biased, while official assurances were treated as neutral. The result was a feedback loop in which those most exposed to harm were least able to influence the framing of its legitimacy.

This racialized discounting of experience is critical to understanding why harm persisted long enough to require judicial intervention. When Black communities report over-policing, discriminatory stops, or geographic targeting, those claims are often treated as political speech rather than empirical evidence. Yet courts later relied on precisely those patterns—corroborated by data and testimony—to find constitutional violations. The difference was not substance. It was institutional willingness to listen.

By the time litigation commenced, many of the contested practices were already normalized. Enforcement strategies had been operational for years. Officers had been trained under their assumptions. Performance metrics had been calibrated to reward their outputs. The costs—lost time, repeated humiliation, erosion of trust—had already been paid by those subjected to routine suspicion. What litigation offered was not prevention, but recognition after the fact.

This chronology matters. It undercuts any claim that judicial findings represented overreach or hindsight bias. Courts did not impose new standards on previously unexamined practices. They intervened after extended periods during which oversight mechanisms failed to test the validity of asserted success. The constitutional violations they identified were not surprises. They were the culmination of warnings unheeded.

Understanding this pre-litigation landscape clarifies the role courts were forced to play. Judicial intervention did not initiate accountability; it substituted for democratic processes that had deferred it too long. The cases that follow did not emerge because harm was unknowable. They emerged because harm was knowable and known—and yet allowed to persist under the protection of narrative certainty.

This section establishes the historical predicate for the analysis that follows. It demonstrates that when courts eventually spoke, they did so against a backdrop of ignored warnings, discounted experience, and oversight delayed past its effective window. The constitutional injuries later identified were not aberrations. They were the foreseeable outcome of governance that privileged narrative over proof and reassurance over rigor.

What follows examines how courts addressed that accumulated harm—not as first responders, but as last resorts.

III. When the Record Finally Broke Through

Courts did not intervene in New York City policing because of abstract disagreement with policy choices. They intervened because the evidentiary record—once forced into view—demonstrated patterns that could no longer be reconciled with constitutional norms. What had been dismissed for years as anecdotal, localized, or politically motivated became, under judicial scrutiny, systemic, measurable, and unlawful.

This shift did not occur because the underlying practices suddenly changed. It occurred because the standards of proof changed.

In democratic and administrative contexts, policing narratives were evaluated through aggregate statistics, executive assertions, and generalized claims of necessity. Courts, by contrast, demanded specificity. They required individualized accounts, distributional analysis, and direct examination of how discretion was exercised in practice. When that scrutiny was applied, the gap between narrative and reality became impossible to ignore.

Central to this reckoning was the exposure of how discretion actually functioned on the ground. Stop practices that had been defended as intelligence-led or behavior-driven were revealed to rely heavily on vague, post hoc justifications. Officers routinely articulated reasons that collapsed into generalizations—presence in a “high-crime area,” perceived nervousness, or non-specific suspicion untethered to observable criminal conduct. These rationales, tolerated administratively, failed constitutional scrutiny.

Importantly, the record showed that such discretion was not randomly distributed. It clustered racially and geographically. Black men were stopped at rates wildly disproportionate to their share of the population and far in excess of any demonstrable link to criminality. Entire neighborhoods experienced saturation enforcement untethered to individualized suspicion, transforming public space into zones of presumptive guilt.

This was not a matter of isolated misconduct. It was a system of permission—one reinforced by performance expectations, managerial pressure, and data regimes that rewarded volume without interrogating legality. Courts recognized that when unlawful practices are incentivized rather than corrected, responsibility cannot be confined to individual actors. The harm becomes institutional.

Equally significant was how data itself functioned as both shield and sword. Internally, activity numbers were used to demonstrate productivity and justify deployment. Externally, aggregate crime declines were cited to validate the very practices producing those numbers. Yet when courts disaggregated the data—examining who was stopped, where, and why—the asserted link between enforcement intensity and public safety collapsed.

The evidentiary record revealed a pattern of enforcement that burdened constitutional rights without demonstrable benefit. Stops overwhelmingly failed to yield weapons, contraband, or arrests. The intrusion was real; the payoff was not. Courts were thus confronted with a system in which the costs of policing were concrete and racialized, while its claimed benefits were speculative and unsupported.

What made judicial intervention unavoidable was not merely the presence of disparity, but the absence of corrective mechanisms. Internal review processes had not meaningfully constrained unlawful discretion. Political oversight had not insisted on attribution discipline. Transparency had been partial and delayed. In that vacuum, constitutional litigation became the only forum capable of compelling disclosure, testing claims, and imposing enforceable limits.

Courts are structurally cautious actors. They do not seek to manage police departments or dictate policy preferences. But they are obligated to act when constitutional violations are demonstrated at scale. In New York City, the record showed not just error, but endurance—practices sustained over years despite mounting evidence of harm.

This is the critical point: judicial intervention was not the product of judicial ambition. It was the consequence of institutional failure elsewhere. Courts did not insert themselves prematurely into policing. They arrived after democratic oversight had failed to interrogate premises while it still could.

Section III establishes that when the record was finally examined under constitutional standards, the narrative of success could not survive. What had been defended as necessary, effective, and data-driven was revealed as overbroad, discriminatory, and detached from demonstrable public safety outcomes.

The next question, then, is not whether courts were right to intervene. It is what that intervention reveals about the cost of delay—and who bore it.

IV. The Racial Cost of Delayed Accountability

The harms addressed by the courts were not evenly distributed. They fell with particular force on Black New Yorkers—especially Black men—whose daily lives were shaped by a policing regime that treated presence as suspicion and routine movement as potential threat. This racial asymmetry is not incidental to the analysis. It is central.

Delayed accountability does not merely postpone correction; it concentrates harm. When unlawful practices persist unchecked, they do so in the spaces where enforcement is most intense and resistance is least institutionally valued. In New York City, those spaces were overwhelmingly Black neighborhoods.

For Black men, the consequences were cumulative and pervasive. Repeated stops without justification imposed costs that rarely appear in official metrics: lost time, public humiliation, psychological stress, and the normalization of state intrusion. These encounters shaped how individuals understood their relationship to government—not as one of protection, but of surveillance and control.

Critically, these harms accrued even in the absence of arrest or formal charge. Constitutional injury does not require prosecution. The Fourth Amendment protects against unreasonable intrusion itself. Courts recognized that a stop unsupported by reasonable suspicion is not rendered lawful by its outcome. The harm lies in the act.

Yet for years, administrative and political discourse minimized this reality. Stops that yielded no enforcement action were framed as preventative or intelligence-gathering. The absence of contraband was treated as neutral rather than probative. Black men were asked, implicitly, to accept routine intrusion as the price of collective safety—despite the lack of evidence that such intrusion produced that safety.

This is where narrative policing intersects with civil rights most sharply. Assertions of success insulated practices from scrutiny precisely where their burdens were greatest. Aggregate crime declines were invoked to justify continued enforcement in neighborhoods already subject to disproportionate policing. The very communities paying the highest constitutional price were told that the strategy was working.

Delayed accountability compounded this injustice. Each year that passed without intervention meant thousands more unconstitutional stops, each individually minor in the eyes of administrators, but devastating in the aggregate. By the time courts imposed constraints, entire generations of Black New Yorkers had experienced policing not as episodic contact, but as a defining feature of public life.

The racial dimension also shaped who was believed. Early warnings from Black communities were discounted or dismissed. Their experiences were treated as subjective grievance rather than evidence of systemic failure. When courts later credited those same experiences—corroborated by data and testimony—the institutional response shifted abruptly from skepticism to compliance. The difference was not the facts. It was the forum.

This pattern underscores a broader civil-rights failure: harm was deemed credible only after it was judicially validated. Democratic institutions did not lack access to information; they lacked willingness to credit it when it came from those most affected. Courts became the arbiters of truth not because they were best positioned to be, but because they were the last remaining venue where proof could not be rhetorically managed away.

Even then, judicial remedies were necessarily limited. Injunctions, monitoring, and reporting requirements can constrain future conduct, but they cannot undo past harm. They cannot restore lost dignity, erase years of unwarranted suspicion, or repair the erosion of trust between Black communities and the institutions meant to serve them. Accountability arrived, but too late to prevent the bulk of the damage.

Section IV thus reframes the cases that follow. They are not merely legal landmarks. They are evidence of accumulated harm that democratic oversight failed to prevent. They document not just unconstitutional practices, but the racialized cost of allowing narrative certainty to override evidentiary rigor.

What follows will examine those cases directly—not as isolated episodes, but as judicial responses to a long-running failure of accountability. Their chronology matters. Their findings matter. And the communities whose rights they vindicated matter most of all.

V. When Courts Replace Oversight: A Judicial History of Predictable Harm

The constitutional violations exposed in New York City policing did not erupt suddenly, nor were they discovered accidentally. They unfolded in a discernible sequence, across time and geography, as enforcement strategies expanded under unproven narratives of success while democratic oversight lagged or receded. Each major case in this history marks not a discrete failure, but a missed opportunity for correction—a moment when earlier warnings went unheeded and harm was allowed to compound.

What emerges from this record is not episodic misconduct, but institutional persistence. The same core logic—suspicion by category rather than conduct, enforcement justified by aggregate crime narratives rather than individualized evidence—reappears in different forms, targeting different spaces, but producing the same constitutional injuries. Black New Yorkers, particularly Black men, appear not as incidental victims of this evolution, but as its consistent subjects.

The courts did not initiate this reckoning. They inherited it.

A. Daniels v. City of New York (1999–2007): The First Warning Ignored

The modern judicial record begins not with Floyd, but with Daniels. Filed in 1999, Kelvin Daniels challenged the practices of the NYPD’s Street Crimes Unit—an elite enforcement apparatus celebrated publicly for its aggressive approach to crime. Plaintiffs alleged what communities had long experienced: suspicionless stops, racially targeted encounters, and routine Fourth Amendment violations carried out under the banner of proactive policing.

Crucially, Daniels was not dismissed as speculative or anecdotal. Judge Shira A. Scheindlin recognized that the plaintiffs plausibly alleged an express racial classification, sufficient to sustain Equal Protection claims. The case resulted in a settlement requiring written anti-profiling policies, audits of stop-and-frisk practices, and training obligations—an early acknowledgment that the problem was systemic rather than individual.

Yet Daniels also illustrates the core pathology that defines this history: oversight without enforcement is not correction. The Street Crimes Unit was disbanded, but the enforcement logic it embodied was not dismantled. The settlement expired. The audits ended. And the practices resumed—rebranded, redistributed, and rejustified through data narratives that claimed success without proving causation.

By 2007, when plaintiffs sought to enforce compliance, Judge Scheindlin directed them to file a new lawsuit. That instruction was not procedural housekeeping. It was a judicial acknowledgment that negotiated reform had failed. The warning had been issued. It had not been heeded.

B. Floyd v. City of New York (2008–Present): From Warning to Liability

Floyd did not arise in a vacuum. It was filed precisely because the post-Daniels regime produced data showing that unconstitutional stops continued at scale. The plaintiffs—four Black men initially, later a certified class—challenged what had become the NYPD’s dominant enforcement strategy: widespread stop-and-frisk, justified through aggregate crime declines and managerial metrics rather than individualized suspicion.

After years of discovery, evidentiary disputes, and a nine-week bench trial, Judge Scheindlin issued findings that stripped away the narrative scaffolding. The scale was industrial: between 2004 and 2012, the NYPD conducted over 4.4 million stops, roughly 88% of which resulted in no enforcement action, exposing millions of innocent New Yorkers to unconstitutional intrusion. It further held that the NYPD violated the Equal Protection Clause by engaging in indirect racial profiling, regardless of whether discriminatory intent could be proven in each instance.

These findings are essential for what they reject. The court did not accept crime reduction claims as self-validating. It did not treat aggregate trends as proof of constitutionality. It examined training materials, supervisory failures, and data patterns—and concluded that the narrative of effectiveness masked systemic illegality.

The remedy imposed—a federal monitor overseeing policies, training, supervision, and discipline—was extraordinary not because it was novel, but because it was overdue. Courts do not assume operational control lightly. They do so when political and administrative mechanisms have exhausted their credibility.

Floyd marks the point at which oversight, long deferred, became judicially compelled.

C. Davis v. City of New York (2010–Present): When Enforcement Moves Indoors

Even as Floyd progressed, the enforcement logic it challenged did not pause. It migrated.

Davis exposed how suspicion-based policing adapted by shifting from public streets into public housing developments. Through “vertical patrols,” officers conducted floor-by-floor sweeps of NYCHA buildings, stopping residents and visitors without individualized suspicion and arresting them for trespass without probable cause. Race and residence became proxies for criminality.

Data revealed that in some precincts, Black and Hispanic men were stopped in public housing at rates double their actual presence in the census population.

The plaintiffs—Black and Latino tenants and their guests—alleged not only Fourth and Fourteenth Amendment violations, but violations of the Fair Housing Act, Title VI, and federal housing statutes. The case revealed a particularly insidious evolution: constitutional norms that applied on sidewalks were treated as optional in stairwells.

Judge Scheindlin’s rulings again rejected the City’s defenses, allowing claims to proceed and ultimately producing a settlement that revised patrol guidelines, imposed documentation requirements, and brought NYCHA enforcement under the Floyd monitoring regime.

Davis matters because it demonstrates that liability findings do not end unconstitutional behavior; they redirect it. When one tactic becomes legally vulnerable, another emerges—often affecting the same populations in spaces with even less visibility and fewer witnesses.

D. Ligon v. City of New York (2012–Present): Geography as Suspicion

Ligon completes the spatial arc. Filed in 2012, it challenged Operation Clean Halls—later renamed the Trespass Affidavit Program—which authorized police patrols in and around private residential buildings designated as “high crime.” In practice, this designation functioned as a standing presumption of suspicion, untethered from actual crime levels and disproportionately imposed on Black and Latino neighborhoods, particularly in the Bronx.

The evidentiary record in Ligon was devastating. Judge Scheindlin relied on five independent categories of proof: testimony from prosecutors declining to pursue unlawful arrests, statistical analysis by Dr. Jeffrey Fagan, uniform plaintiff accounts, and NYPD training materials misstating constitutional standards. The court issued a preliminary injunction, ordering the NYPD to cease suspicionless trespass stops around TAP buildings.

Ligon is not merely an extension of Floyd. It is its geographic corollary. Where Floyd addressed stop-and-frisk broadly, Ligon demonstrated how place itself became a proxy for suspicion—how entire buildings and neighborhoods were transformed into zones of diminished constitutional protection.

Together, Daniels, Floyd, Davis, and Ligon reveal a pattern: enforcement strategies expanding outward and inward, adapting faster than oversight, consistently burdening the same communities.

E. Monitoring, Resistance, and the Illusion of Closure

The imposition of a federal monitor did not end this history. It extended it.

The Twenty-Seventh Monitor’s Report (2025) documents what a decade of supervision has failed to cure: persistent unlawfulness in self-initiated encounters, chronic underreporting, and a yawning gap between frontline supervisory review and independent audits. Lawfulness rates for stops, frisks, and searches remain unacceptably low. Supervisors continue to flag only a fraction of unconstitutional conduct identified by monitors.

This is not drift. It is structural inertia.

The Yates Report highlighted that even when the CCRB substantiated misconduct, the Police Commissioner departed from those recommendations in nearly 71% of cases, neutralizing the deterrent effect of discipline.

These reports matter because they dismantle the final refuge of narrative policing: the claim that reform is complete because monitoring exists. Monitoring without enforcement is observation, not correction. It records harm; it does not prevent it.

F. The Through-Line: Predictability, Not Surprise

Taken together, these cases do not tell a story of sudden revelation or isolated misconduct. They tell a story of predictable escalation. Each judicial intervention responded to harms that were foreseeable from the last. Each remedy addressed practices that had already entrenched themselves.

The common denominator is not officer intent or even departmental culture. It is governance by narrative—policy justified by asserted success rather than demonstrated causation, shielded from timely scrutiny, and corrected only after courts were forced to intervene.

For Black New Yorkers, particularly Black men, this history is not academic. It is lived. It is the cumulative effect of being repeatedly positioned as the raw material of public safety metrics—stopped, searched, arrested, and counted, long before the numbers were ever questioned.

Section V establishes what the record makes unavoidable: courts did not overstep. They stepped in where oversight had already stepped out.