When The New York Times published its November 11, 2025 article, “How Do You Judge Whether a Police Officer Is Mentally Fit for the Job?”, it presented what it described as a serious policy dilemma: how to evaluate police officers who “fail psychological exams.”

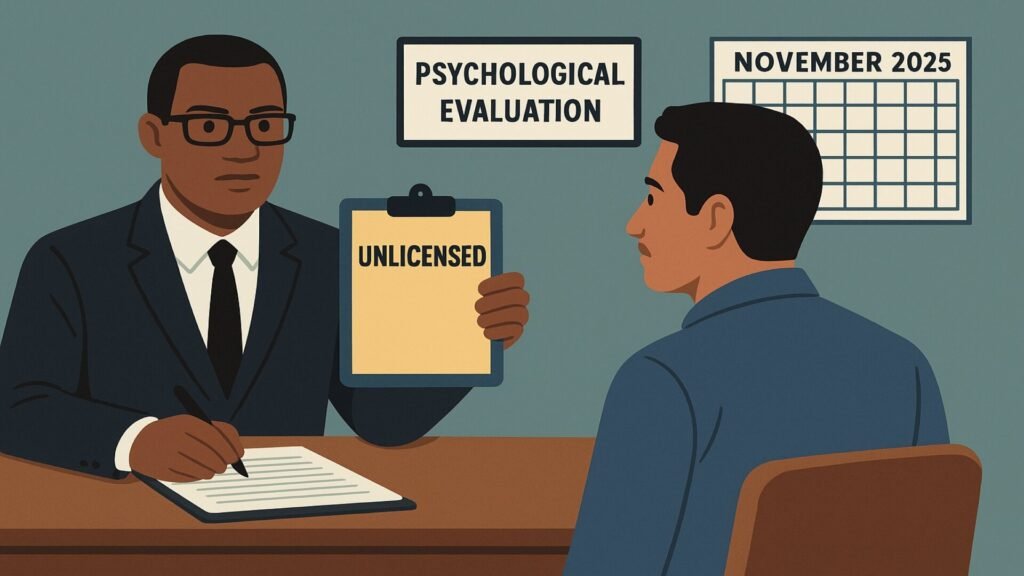

The problem is that the premise itself is false. There is no such thing as a legally defined, scientifically validated “police psychological exam” in New York State. What the Times accepted as fact is, in truth, an unlawful and unregulated opinion process masquerading as psychological science.

By uncritically adopting the NYPD’s framing, the Times didn’t illuminate a complex issue — it legitimized a fiction. The article’s tone and structure convey to readers that the Department’s methods are standard practice, professionally administered, and rooted in objective assessment. They are none of those things.

I. The Premise Is False: No Law Authorizes a “Police Psychological Exam”

The Times piece begins from an unexamined assumption: that “psychological exams” are a normal part of law-enforcement hiring, backed by clear legal authority and professional standards. But under New York Education Law, no such mechanism exists.

The practice of psychology is defined by statute — Education Law § 7601-a — as the observation, evaluation, and modification of behavior for the purpose of determining mental or emotional health, including in employment contexts. That activity may only be performed by individuals licensed as psychologists under Article 153, or by those operating under a limited permit pursuant to § 7605, which requires direct supervision by a licensed psychologist.

Yet, for decades, the NYPD has allowed unlicensed or improperly supervised personnel — often uniformed officers or civilian employees — to conduct “psychological interviews” and issue opinions that determine whether an applicant can work as a police officer. These decisions carry enormous legal consequences, yet they are made outside the boundaries of professional licensure and without oversight by the State Education Department’s Office of the Professions.

The Times did not ask the obvious question: Who are these psychologists? Are they licensed? Under what law do they operate? By failing to ask, the article transmuted illegality into legitimacy. It presented an administrative convenience as a scientific process, reinforcing the illusion that this practice is normal, lawful, and reliable.

II. The Category Error: Clinical Subjectivity Posing as Forensic Objectivity

The article repeatedly refers to “psychological tests,” “evaluations,” and “exams,” suggesting a rigorous forensic process — one designed to measure job-relevant psychological competence. But the evaluations the NYPD uses are not forensic; they are clinical.

This distinction matters.

A forensic psychological evaluation must be objective, standardized, and validated for the specific legal or occupational purpose it serves. It relies on data, statistical reliability, and measurable correlations to job performance.

A clinical evaluation, by contrast, is subjective and interpretive. It is designed for therapeutic insight, not legal determination. Tools like the MMPI-2, CPI, or 16PF — commonly used by police departments — were never developed for employment screening. They measure general personality or psychopathology, not suitability for police work.

When used in hiring, these tools transform into pseudo-forensic instruments — opinion-based filters that reflect examiner bias far more than scientific validity. The NYPD’s process conflates these categories completely. Its “psychological exam” is nothing more than a subjective interview paired with inappropriate test batteries, analyzed by individuals who may not even hold the licenses required to interpret them.

The Times never interrogated that contradiction. Instead, it described this hybrid process as though it were both lawful and scientific. In doing so, it perpetuated one of the most persistent myths in American policing: that subjectivity cloaked in professional language equals objectivity.

III. Journalism Without Verification: How the Times Became a Conduit

The responsibility of serious journalism is to verify institutional claims, not repeat them. Yet in this case, the Times adopted the NYPD’s terminology wholesale — referring to “failed psychological exams,” “department psychologists,” and “fitness evaluations” as though these were established professional constructs.

A single call to the New York State Education Department would have revealed that there is no statutory category called a “police psychologist.” The Department does not recognize any license or certification by that name. The NYPD’s “psychologists” are internal employees, not a legally distinct professional class.

By neglecting this due diligence, the Times blurred the line between regulation and rhetoric. It reported the appearance of expertise instead of examining its absence. That is not investigative reporting; it’s institutional stenography.

The damage goes beyond one article. When a newspaper with the reach of The New York Times treats an unlawful practice as legitimate, it shapes public understanding. Readers assume that if the Times describes a process as an “exam,” it must exist within a legal and scientific framework. It does not — and the article’s failure to clarify that point is not an oversight. It is a profound abdication of journalistic responsibility.

IV. The False Assurance of Science

The language of the Times article trades heavily on the idea that the psychological evaluation process is objective — that candidates “fail” or “pass” based on measurable qualities like “emotional regulation” or “decision-making.” Those phrases sound technical, but they have no quantifiable meaning in this context. They are evaluative shorthand, not diagnostic or forensic categories.

In legitimate psychometrics, objectivity is achieved through standardization, reliability, and validity testing. To be used in hiring, a psychological instrument must meet the federal standards set by the Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures (UGESP), 29 C.F.R. § 1607. These guidelines require:

Documented criterion validity — showing that the test actually predicts job performance;

Evidence of reliability — demonstrating consistent results across examiners and populations;

Proof that the tool is free from disparate impact based on race, ethnicity, or gender.

The NYPD has never publicly produced validation data meeting any of those requirements. Yet the Times article cited “department psychologists” as though they were administering a scientifically validated process. By doing so, the paper granted scientific legitimacy to a system that is neither scientific nor legitimate.

V. The Ethical Consequences: Disparate Impact and Cultural Bias

Even as the article noted concerns about minority candidates being disproportionately disqualified, it failed to connect those outcomes to the absence of validation or compliance with federal law. Under UGESP, if a test disproportionately excludes protected groups — as these psychological “exams” routinely do — the employer must prove that the test is job-related and consistent with business necessity.

The NYPD cannot make that showing because its assessments are subjective. There are no predictive data, no reliability studies, and no demonstrable link between the traits measured and actual job performance. The result is a self-fulfilling cycle: evaluators, steeped in institutional norms, disqualify candidates whose experiences diverge from their own cultural expectations.

The Times reduced this to a passing observation — that “some say the test doesn’t account for different life experiences.” But that is not a matter of perception; it is a structural violation of both federal employment law and basic professional ethics. When a major newspaper treats systemic discrimination as a matter of “debate,” it transforms illegality into mere controversy.

VI. Professional Misrepresentation and the Erosion of Accountability

Perhaps the most misleading aspect of the Times coverage is its uncritical use of the term “department psychologist.” That phrase implies professional independence and regulatory oversight. In reality, these individuals are employees of the very agency whose hiring decisions they validate. They are not neutral experts; they are institutional actors operating without external accountability.

A forensic evaluator must be independent of the parties affected by the evaluation. That is a basic tenet of professional ethics. The NYPD’s model collapses that separation entirely. It allows the Department to act as both examiner and employer — a conflict of interest that would be unacceptable in any legitimate forensic context.

By describing these individuals as “psychologists” without verifying licensure or professional status, the Times helped the Department cloak administrative subjectivity in the language of expertise. That linguistic sleight of hand turns bureaucratic opinion into “science” and makes the unlawful appear lawful.

VII. The Manufactured Legitimacy of Pseudo-Science

The broader consequence of this journalistic failure is the manufacture of legitimacy. Each time the press uses the phrase “psychological exam” without qualification, it reinforces the illusion that there is a standardized, lawful, and evidence-based process behind it.

That illusion has real-world effects. Candidates who are disqualified on the basis of these opinions often believe — as the Times would have them believe — that they have failed a genuine scientific test. In reality, they have been excluded by an unvalidated and unlicensed apparatus that answers to no regulatory body.

This isn’t science. It’s bureaucracy wearing a lab coat.

The Times could have exposed that contradiction. Instead, it repeated it, lending its brand of credibility to one of the most enduring myths in police administration: that psychological “fitness” is something you can measure without law, license, or evidence.

VIII. The Human Cost of Institutional Convenience

What’s missing from the Times narrative is the human cost. When candidates are labeled “psychologically unfit,” that stigma follows them for life. It affects future employment, professional reputation, and self-worth. Yet the determinations are often based on trivialities: adolescent behavior, counseling history, or misinterpreted statements during subjective interviews.

Worse, these determinations are rendered by evaluators operating under institutional pressure — aware that rejecting a candidate poses no risk, while approving one who later faces scrutiny could end their own career. The result is a system structurally incentivized toward over-exclusion.

That system is not protecting public safety; it is protecting itself. And by presenting that system as legitimate, the Times inadvertently participated in its preservation.

IX. The Broader Implications: Journalism and Power

This episode is not merely about the NYPD. It is about how journalism interacts with power. When reporters adopt the language of authority without examining its foundations, they become part of the machinery they are supposed to scrutinize.

The Times article reads like a case study in what happens when institutional deference replaces investigative rigor. The reporter spoke to officers, lawyers, and psychologists — but not to regulators, not to licensing authorities, and not to experts in forensic assessment who could have explained why the entire premise is untenable.

In doing so, the Times provided readers with a moral drama — some officers unfairly rejected, others justifiably disciplined — but no factual understanding of the system’s legal or scientific legitimacy. It framed a bureaucratic failure as a moral debate, allowing readers to feel informed while leaving the central fiction untouched.

X. What Real Journalism Would Have Asked

A journalist seeking the truth would have asked:

What statutory authority governs the NYPD’s psychological evaluations?

Who are the evaluators, and are they licensed psychologists under New York Education Law?

What validated instruments are used, and where are the published reliability and validity studies?

How does the Department ensure compliance with federal anti-discrimination standards under 29 C.F.R. § 1607?

What independent oversight exists to prevent misuse of psychological opinions in hiring or discipline?

None of these questions appeared in the Times story. Instead, readers were left with the impression that the issue is simply one of fairness — whether “some officers” are treated unjustly. The real issue is legitimacy: whether the process itself has any lawful or scientific foundation.

XI. The Real Story: Power Without Oversight

The NYPD’s psychological evaluation process exemplifies what happens when administrative power operates without regulation. It allows unlicensed personnel to render unreviewable judgments about mental fitness, using unvalidated tools, in a system with no transparency. That is not public safety; it is institutional self-preservation.

By failing to expose that reality, the Times not only misinformed its readers — it perpetuated the very opacity it should have challenged. Its article functions as an endorsement of the status quo, reinforcing the myth that exclusionary systems are inherently protective.

But public safety does not come from unregulated power. It comes from accountability, transparency, and the rule of law — the very principles ignored in both the NYPD’s practice and the Times’ reporting.

XII. Conclusion: Journalism’s Duty to Truth, Not Authority

The New York Times has long positioned itself as the paper of record, a guardian of factual rigor and public trust. Yet in this case, it failed in that duty. By presenting the NYPD’s pseudo-scientific screening process as legitimate, it helped entrench an unlawful practice and misled the public about both psychology and policing.

The paper did not merely misunderstand a technical issue; it validated a fiction. It told readers that there is such a thing as a “police psychological exam,” that it measures something real, and that it operates under lawful authority. None of those claims are true.

The NYPD’s “psychological exam” is not an exam, not psychological in the scientific sense, and not lawful under New York’s professional-licensing statutes. It is a bureaucratic instrument of control — a tool of exclusion disguised as expertise.

And now, thanks to the Times, it carries the imprimatur of the nation’s most influential newspaper.

That is why this critique matters. When powerful institutions — police departments, city governments, or national newspapers — converge to construct and reinforce a shared illusion, it is not just misinformation; it is structural deception. The public deserves better. The law demands better. And the truth requires that we call this system what it is: a legal and scientific fiction.