I. Introduction: The Misplaced Debate

The contemporary debate surrounding qualified immunity is fundamentally misplaced. It is framed almost exclusively as a contest of competing policy goals: on one side, the need to shield government officials from the chilling effects of litigation, and on the other, the urgent necessity of providing a remedy for citizens whose constitutional rights have been violated. This framing, which presents the issue as a balancing act for the judiciary to perform—weighing the “dampened ardor” of public servants against the vindication of civil liberties—is a profound misapprehension of the legal question at hand. It treats the existence of immunity as a legitimate judicial choice, a matter of prudential policy to be debated and reformed.

This entire discourse is built upon a false premise. The central issue is not whether qualified immunity is good or bad policy, but whether it is lawful. The doctrine, a judicial invention of the twentieth century, stands in direct and irreconcilable conflict with the express statutory command of the law it purports to interpret: Section 1 of the Civil Rights Act of 1871, the great legislative achievement of the Reconstruction Congress, now codified as 42 U.S.C. § 1983. The Court’s decades-long project of judicial policymaking, which openly weighs the “social costs” of litigation against individual remedies, is an exercise made possible only by ignoring the actual law passed by Congress.

The thesis of this analysis is unambiguous: Qualified immunity should be abolished not as a matter of policy preference, but because it is textually and historically incompatible with the original mandate of the statute. For over half a century, the Supreme Court has predicated the doctrine upon a foundational error—the assumption that the 42nd Congress enacted § 1983 in silence against a backdrop of common-law immunities it implicitly intended to preserve. This judicial presumption, which became the lynchpin of qualified immunity, is not merely incorrect; it is a historical falsehood.

The original text of the 1871 Act was not silent. It contained a powerful and explicit textual command, a “lost clause” that has been ignored by the courts for generations. This provision, a “Notwithstanding Clause,” was specifically designed by its drafters to override and displace the very state laws, customs, and common-law defenses that the Supreme Court has painstakingly reassembled in the form of qualified immunity. Its disappearance from the modern U.S. Code was the result of a clerical revision for stylistic concision, not a substantive act of legislative repeal.

By restoring this omitted mandate to its rightful place, the illegitimacy of qualified immunity becomes a matter of statutory fidelity, not judicial policymaking. The doctrine is not a mere “contour” of the statute; it is a judicial reconstruction that flagrantly contradicts the will of Congress. The debate must therefore be reframed. We must move past the misguided policy calculus and ask the primary question of law: what did the statute, as written and enacted, actually command? Answering that question reveals that the law to abolish qualified immunity has been on the books for over 150 years. The courts simply need to enforce it.

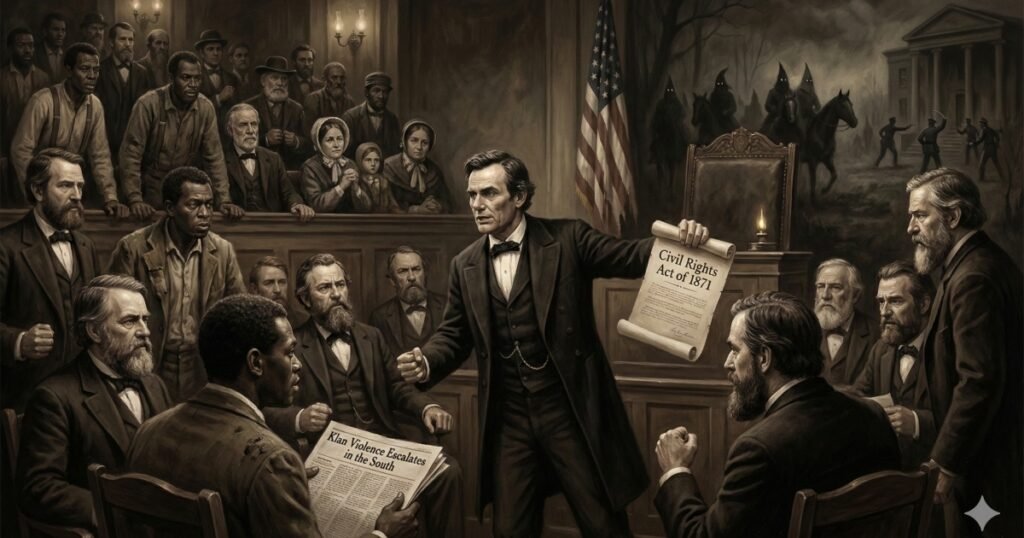

II. The Civil Rights Act of 1871: A Tool Forged in Crisis

To comprehend the radical and uncompromising nature of Section 1 of the Civil Rights Act of 1871, one must first understand the crisis from which it was born. The Act was not a piece of ordinary legislation; it was an emergency measure, a fundamental reordering of American federalism designed to combat a state of lawlessness that threatened the very survival of the Union and the promises of emancipation. It was, in the words of its drafters, a “strong medicine” for a nation in peril.

The years following the Civil War and the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment did not bring peace or freedom to the newly emancipated Black citizens of the South. Instead, Southern state governments, restored to power, enacted the infamous Black Codes, a web of discriminatory laws that effectively nullified the amendment’s protections and sought to re-establish a system of racial subjugation. Simultaneously, a campaign of private terror, spearheaded by the Ku Klux Klan, swept across the region. The Klan systematically and ruthlessly perpetrated what became known as “outrages”—beatings, whippings, lynchings, shootings, rapes, and murders—to prevent Black people from exercising their basic civil and political rights. This was not random violence; it was, as one historian described it, a campaign of “barbaric savagery” designed to terrorize and disenfranchise.

This reign of terror was enabled by the complicity of state and local officials. The law enforcement and judicial systems of the former Confederacy had become instruments of oppression. The problem was not merely the existence of discriminatory statutes, but the willful failure of state agents to enforce any law that protected the rights of the freedmen. As one member of the House of Representatives lamented before his colleagues, the apparatus of state justice had utterly failed. In the face of Klan violence, he observed that, “[s]heriffs, having eyes to see, see not; judges, having ears to hear, hear not;” and “all the processes of justice[] skulk away as if government and justice were crimes and feared detection.” State courts and officials, either through active participation or willful neglect, allowed violence and the deprivation of rights to proceed with impunity.

It was in this crucible of state-sanctioned anarchy that the 42nd Congress acted. The purpose of the Civil Rights Act of 1871 was nothing short of revolutionary. It sought to transform the very premise of the nation’s founding-era federalism. For the first time, Congress would “interpose the federal courts between the States and the people, as guardians of the people’s federal rights.” The federal government, through its judiciary, would step in where states had failed, providing a forum for redress against any state official who deprived a citizen of their constitutional rights. This was a deliberate and foundational shift in the balance of power between the state and federal governments, a recognition that the original constitutional design had failed to protect the most vulnerable citizens.

The statute’s constitutional mission was emblazoned in its official title: “An Act to enforce the Provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, and for other Purposes.” This was not merely a law about torts; it was a law about enforcing the nation’s highest charter against recalcitrant states and their agents. The men who drafted this legislation were not engaged in a subtle exercise of common-law interpretation. They were forging a weapon to secure the promises of a bloody war and to give life to the new constitutional amendments. They intended it to be powerful, direct, and free from the very local customs and legal traditions that had, for years, served as a shield for oppression.

III. The Original Text: An Unmistakable Command of Liability

The analytical core of the case against qualified immunity lies not in policy arguments or moral appeals, but in the plain, unvarnished text of the law as it was written. The language chosen by the 42nd Congress in 1871 was not, as the Supreme Court would later suggest, “loose and careless.” It was deliberately and “expressly sweeping,” crafted with precision to achieve its revolutionary purpose. An honest examination of the original statutory language reveals a clear and unambiguous command of liability, a command that leaves no room for the exceptions and immunities the judiciary would later invent.

A. The Full Statutory Language

To understand what the law requires, we must first read the law as it was enacted. The operative text of Section 1 of the Civil Rights Act of 1871, as it appears in Volume 17, Page 13 of the United States Statutes at Large, is the only authoritative version of the law. It reads:

“Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That any person who, under color of any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage of any State, shall subject, or cause to be subjected, any person within the jurisdiction of the United States to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution of the United States, shall, any such law, statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage of the State to the contrary notwithstanding, be liable to the party injured in any action at law, suit in equity, or other proper proceeding for redress…”

The command is absolute. Any state actor who causes the deprivation of a constitutional right “shall… be liable.” There are no qualifiers, no exceptions, and no references to good faith, reasonableness, or the state of pre-existing case law. The liability is a direct and necessary consequence of the constitutional injury.

B. The “Notwithstanding Clause”: A Textual Bomb

The most critical—and most tragically ignored—portion of this text is the clause that modern scholarship has termed the “Notwithstanding Clause”: “any such law, statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage of the State to the contrary notwithstanding”. This was not redundant or superfluous language. It was a textual bomb, a provision deliberately designed by the bill’s drafters to blow through any and every potential defense rooted in state authority or local legal tradition. Representative Samuel Shellabarger, the bill’s House manager, added the clause specifically to ensure that the list of state legal authorities could not be used as a shield against federal accountability.

The clause creates what has been aptly described as a “reflexive liability loop.” It takes the preceding list of state legal sources under which an official might act—”law, statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage”—and repurposes it as a definitive instruction to the judiciary. The syntax is a masterpiece of legislative precision. The use of the word “such” before the list of state authorities directly refers back to the same list that establishes the “under color of” element of the offense. The clause effectively commands that if an official acts under color of any state law or custom, that same state law or custom is explicitly nullified as a defense to liability.

In practical terms, the clause instructs federal courts to disregard any state-level legal authorities that stand in the way of a remedy. Congress did not simply create a new federal cause of action; it simultaneously and explicitly disarmed the anticipated defenses. It anticipated that state officials would argue that their actions were authorized or even mandated by a state statute, sanctioned by local ordinance, or protected by entrenched custom. The Notwithstanding Clause was Congress’s preemptive strike against all such arguments, a textual command to prioritize the federal remedy above all else.

C. Displacing Common Law “Custom”

Within this powerful clause, the inclusion of the word “custom” carries profound legal significance. In the legal lexicon of 1871, “custom” was a standard term of art used to refer to the unwritten common law—the body of rules and precedents established by judicial decisions rather than by legislative enactment. The Reconstruction Congress was fighting a war on two fronts: against the discriminatory formal statutes of the Southern states, and against the equally pernicious unwritten “customs” of official complicity and common-law defenses that rendered those statutes effective. The drafters of the 1871 Act were not naive; they were sophisticated lawyers and legislators who understood that official impunity was often grounded not in formal statutes but in long-standing common-law traditions and judicial doctrines, including immunities that historically protected state officers.

By explicitly stating that liability would attach “notwithstanding… custom,” the Reconstruction Congress issued a direct and unmistakable command to the federal courts: displace the common-law rules that shield state officials. This single word demolishes the central pillar upon which the Supreme Court later built the doctrine of qualified immunity—the idea that Congress legislated in silence, implicitly intending to preserve the “settled” common-law immunities of 1871. Congress was not silent; it spoke directly to the issue, and it mandated that common-law custom must yield to the new federal remedy. The clause was a comprehensive disarmament of all state-level legal authority that could be invoked to defeat a federal civil rights claim.

D. A Strict Liability Statutory Tort

The structure of the statute confirms that Congress keyed liability to the constitutional deprivation itself, without inserting a fault or intent prerequisite into the cause of action. The focus of the cause of action is entirely on the harm inflicted upon the victim—the “deprivation of any rights”—not on the fault or state of mind of the perpetrator. The only operative questions under the plain text are (1) whether a person acting under color of state law (2) subjected a person to the deprivation of a right secured by the Constitution. If the answer to both is yes, liability attaches. The statute imposes liability for the injurious act itself, making it a classic harm-based tort.

This legislative choice was deliberate. The same Congress that enacted Section 1 of the Civil Rights Act of 1871 knew precisely how to write a fault-based cause of action when it wished to do so. This was a body of lawmakers who demonstrated a mastery of legal drafting, making the absence of a fault standard in Section 1 a deliberate and unmistakable choice, not an oversight. In other sections of the very same Act, Congress included explicit fault requirements. Section 2 of the Act (now codified in part at 42 U.S.C. § 1985(3)) made conspiracies actionable only where the tortfeasor acted with “the purpose… of depriving any person… of the equal protection of the laws.” Section 6 (now codified at 42 U.S.C. § 1986) imposed bystander liability only on those “having knowledge” of a conspiracy who “neglect or refuse” to prevent it.

The contrast could not be starker. For Sections 2 and 6, Congress required proof of purpose and knowledge. For Section 1, it required only the act of deprivation. The drafters made a conscious and calculated decision to impose strict liability for the constitutional harms covered by Section 1, ensuring that the victim’s right to redress would not be contingent on proving the malevolent intent or negligence of the state official who violated their rights. The focus was, and was always meant to be, on making the injured party whole.

E. “Every Person”: The Deliberate Breadth of Reconstruction Liability

The breadth of Section 1’s liability command is reinforced by another phrase the modern qualified-immunity doctrine has quietly neutralized: Congress’s choice to impose liability on “any person” who, under color of state law, causes the deprivation of a constitutional right. That phrase was neither casual nor accidental. In the statutory vernacular of the Reconstruction era, “any person” was language of inclusion, not ambiguity. It signaled Congress’s intent to cast the net of accountability broadly—wide enough to encompass precisely the class of state actors who had, for generations, operated beyond the reach of meaningful legal consequence.

The Supreme Court has frequently treated the phrase “any person” in § 1983 as if it were a term of art riddled with implied exceptions. But that interpretive instinct is anachronistic. In the mid-nineteenth century, when Congress wished to exempt categories of actors from liability—judges, legislators, or executive officers—it did so expressly. Federal statutes of the period routinely carved out immunities, limitations, or scienter requirements with unmistakable clarity. The absence of such carve-outs in Section 1 of the 1871 Act is therefore not a gap to be filled by judicial inference; it is an affirmative drafting choice.

This point bears emphasis because the Court’s qualified-immunity jurisprudence rests on the opposite assumption: that Congress must have intended to preserve common-law immunities unless it unmistakably abrogated them. That assumption collapses under scrutiny. Congress did unmistakably abrogate them—first through the “Notwithstanding Clause,” and second through the unqualified imposition of liability on “any person.” Read together, these provisions form a cohesive statutory design. The former strips away state-law defenses; the latter identifies the full universe of potential defendants. There is no textual warrant for reading into “any person” a silent exclusion for officials acting in good faith, reasonably, or without prior judicial notice.

Indeed, the legislative debates surrounding the Civil Rights Act of 1871 confirm that Congress understood exactly how far this language would reach. Opponents of the bill repeatedly objected that its terms would expose state judges, prosecutors, and law-enforcement officers to personal liability for actions taken in the course of their official duties. Those objections were not brushed aside as misunderstandings; they were met head-on and rejected. The breadth of the phrase “any person” was not lost on the 42nd Congress. It was the point.

What modern doctrine treats as an intolerable consequence—the prospect that state officials might be held liable for constitutional violations absent proof of bad faith—was, for the Reconstruction Congress, a necessary corrective. Congress had witnessed, in real time, how discretionary authority cloaked in good intentions could coexist with systematic constitutional abuse. The problem was not merely malicious actors; it was an entire apparatus of governance that functioned without accountability. By imposing liability on “any person” who caused a constitutional deprivation, Congress shifted the focus from the official’s subjective mindset to the objective harm inflicted on the citizen.

This understanding also undercuts the frequent claim that § 1983 must be read against a background presumption of official immunity in order to preserve governmental functionality. The Reconstruction Congress was fully aware that its statute would alter the operating conditions of state governance. It enacted Section 1 precisely because the existing equilibrium—one in which officials enjoyed broad immunity and victims were left remediless—was intolerable. The statute was designed to change behavior by changing incentives, ensuring that constitutional rights would no longer depend on the grace or goodwill of those entrusted to enforce them.

The modern qualified-immunity doctrine effectively rewrites the phrase “any person” to mean “any person except those performing discretionary governmental functions, unless their conduct violated clearly established law.” That limiting language appears nowhere in the statute Congress enacted. It is not a reasonable construction of ambiguous text; it is a judicial amendment. When the Court insists that Congress must speak more clearly to impose liability on officials, it is not interpreting § 1983—it is demanding a clarity standard that Congress already satisfied in 1871.

In short, “any person” means what it says. It reflects a deliberate legislative judgment that no category of state actor should be categorically shielded from accountability for constitutional violations. To read that phrase as silently incorporating a complex regime of immunities is to invert the statute’s structure and to nullify one of its most fundamental commands. The Reconstruction Congress did not whisper liability; it declared it.

IV. The Disappearing Clause: How Clerical Conciseness Rewrote American Law

The explicit command of liability embedded in the 1871 Act was not repealed by a subsequent Congress. It did not fade from the law through judicial interpretation. It vanished from view because of an administrative process of legal consolidation, a clerical effort at conciseness that had the unintended consequence of rewriting one of the most important civil rights statutes in American history. The “silence” upon which the Supreme Court built qualified immunity is not legislative; it is a ghost, a clerical artifact of the 1874 codification of federal law.

In the early 1870s, federal law was a chaotic and nearly inaccessible thicket of legislation. The statutes were scattered across seventeen volumes of the Statutes at Large, making it “practically impossible” for lawyers and judges to reliably determine the current state of the law. To bring order to this disarray, Congress authorized a commission of revisers to compile and consolidate all general and permanent federal statutes into a single, organized code. This massive undertaking culminated in the enactment of the Revised Statutes of 1874.

During this process, Section 1 of the Civil Rights Act of 1871 was extracted, renumbered, and reenacted as Revised Statutes § 1979. In rephrasing the text, the revisers made several changes. They moved the jurisdictional language to other sections of the code and, most momentously, they omitted the “Notwithstanding Clause” in its entirety.

Crucially, the historical record demonstrates that this omission was intended to be a stylistic edit for the sake of concision, not a substantive repeal of the law’s command. The prevailing view among nineteenth-century legal drafters was that such “notwithstanding” clauses were often redundant. The primary statutory command—in this case, “shall be liable”—was considered sufficient on its own to automatically displace any contrary law or custom. The revisers, under immense pressure to condense thousands of pages of statutes, believed that the clause was “immaterial” and that the core meaning of Section 1 would be preserved “without that clause.” They saw themselves as trimming lexical fat, not performing legislative surgery.

The revisers and the 43rd Congress did not intend to alter the law’s meaning. To ensure that the original intent was preserved in cases of doubt, they implemented a standard contingency plan. In the margins next to the new text of § 1979, the revisers included a citation directing the reader back to the original statute: “17 Stat. 13.” This note was a formal instruction, designed to direct judges and lawyers back to the authoritative text of the Statutes at Large to resolve any ambiguity. It was an acknowledgment that the codification was a convenience, not a replacement for the original source law.

This history is not merely academic. It is governed by a bedrock principle of American law: the act of codifying statutes cannot amend their substantive meaning unless Congress explicitly states its intention to do so. Where a discrepancy exists between the original text in the Statutes at Large and its later codification in the Revised Statutes or the modern U.S. Code, the original enactment controls. This principle is especially potent with respect to Title 42 of the U.S. Code, which contains § 1983. Title 42 has never been enacted as positive law. This means that while the U.S. Code is a convenient reference, it is legally only a preliminary guide, or prima facie evidence of the law. In any conflict, the authoritative text is not what is printed in the modern blue book, but what is found in the Statutes at Large. Legally, the “Notwithstanding Clause” has never left the statute.

Therefore, the silence in the modern version of 42 U.S.C. § 1983 is an illusion. The entire legal foundation of qualified immunity is therefore built not on a rock of legislative intent, but on the sand of a clerical error—an error the Court failed to identify because it neglected to read the authoritative version of the very law it was interpreting.

A. Codification Is Not Repeal: Why Courts Have Been Reading the Wrong Statute

The modern doctrine of qualified immunity rests on a foundational interpretive mistake: the assumption that the silence of the current U.S. Code reflects the intent of the Reconstruction Congress. It does not. That silence is not legislative. It is the product of nineteenth-century codification—a clerical process that reorganized federal statutes for convenience, not a substantive act of amendment or repeal.

To understand how this error arose, it is essential to distinguish between two very different sources of federal law. The Statutes at Large contain the authoritative text of every act of Congress as it was enacted. The United States Code, by contrast, is a later organizational compilation. Unless Congress has enacted a title of the Code as positive law, the Code is not itself the law; it is only prima facie evidence of the law. In the event of a discrepancy, the Statutes at Large control.

That distinction is decisive here. Title 42 of the United States Code—the title in which § 1983 appears—has never been enacted as positive law. As a result, the legally controlling version of § 1983 is not the streamlined text printed in the modern Code, but the language Congress enacted in 1871 and preserved in the Statutes at Large. Any interpretive methodology that treats the codified text as dispositive, while ignoring material omitted during codification, is legally unsound.

The omission of the “Notwithstanding Clause” occurred during the 1874 revision that produced the Revised Statutes. That revision was authorized for a limited purpose: to consolidate and simplify existing federal statutes without changing their meaning. The revisers were not empowered to amend substantive law, and nothing in the legislative record suggests that Congress intended the revision process to narrow the scope of civil-rights liability. To the contrary, the revision act expressly disclaimed any intent to alter substantive rights.

At the time, “notwithstanding” clauses were often viewed as stylistic emphases rather than substantive innovations. The revisers, charged with condensing thousands of pages of statutes into a coherent code, treated such clauses as surplusage where the operative command appeared otherwise clear. In their view, the directive that an official “shall be liable” already carried preemptive force against contrary law or custom. The deletion of the clause was therefore understood as an act of concision, not repeal.

That understanding was made explicit in the margins of the Revised Statutes themselves. Next to Revised Statutes § 1979—the provision that would later become § 1983—the revisers included a cross-reference to the original enactment: “17 Stat. 13.” This was not decorative. It was an instruction to courts and practitioners to consult the Statutes at Large to resolve ambiguity or uncertainty. The codification was meant to be a guide, not a substitute for the enacted law.

Yet over time, courts lost sight of this hierarchy. As the U.S. Code became the dominant reference point for statutory interpretation, the omitted clause faded from judicial awareness. What had been a drafting convenience hardened into an interpretive assumption: that Congress had spoken in silence about immunity. That assumption, in turn, became the doctrinal foundation for qualified immunity.

This is not how statutory interpretation is supposed to work. Courts do not have the authority to treat codification choices as implied amendments—particularly when those choices were made by revisers operating under explicit constraints not to alter substantive law. Where a civil-rights statute enacted by Congress contains an express liability command, courts may not narrow that command by pointing to language removed for stylistic reasons during a non-positive-law compilation.

The consequences of this mistake have been profound. By mistaking codification for repeal, the Supreme Court built an immunity doctrine on the absence of words that Congress actually wrote and enacted. The resulting jurisprudence does not reflect congressional silence; it reflects judicial reliance on an incomplete text. Once the Statutes at Large are restored to their proper role, the premise underlying qualified immunity collapses.

V. The Judicial Invention of Immunity: Building a Doctrine on a False Premise

The clerical omission detailed in the previous section did not remain a dormant historical footnote. Instead, it created an interpretive vacuum—a phantom silence—that the Supreme Court would rush to fill, not with historical inquiry, but with its own policy preferences. The doctrine of qualified immunity was built, brick by brick, upon this void. It is a judicial creation, constructed over several decades by a Court that either was unaware of or chose to ignore the original text of the Civil Rights Act of 1871. The doctrine’s development is a case study in judicial legislation, moving progressively further from the law’s text and history and deeper into the realm of pure policy-making.

A. Pierson v. Ray and the Myth of Congressional Silence

The foundational case for qualified immunity is Pierson v. Ray (1967). The case involved a group of clergymen arrested for attempting to use a segregated bus terminal in Jackson, Mississippi. In deciding whether the police officers could be held liable under § 1983, the Supreme Court confronted the statute’s absolute language, which makes “every person” who deprives another of their rights liable. The Court, however, looked at the codified text, saw no explicit mention of immunities, and from this perceived silence, inferred a congressional intent to preserve them.

The majority’s central reasoning established the false premise that has defined the doctrine ever since. The Court held that the common-law defenses available to police officers were not abolished by § 1983, reasoning that the Court could not presume that the Reconstruction Congress had intended such a radical departure from tradition without saying so directly. In the Court’s own words:

“we presume that Congress would have specifically so provided had it wished to abolish the doctrine.”

This judicial presumption, which became the lynchpin of qualified immunity, is not merely incorrect; it is a historical falsehood. As the full text of the 1871 Act proves, Congress did specifically so provide. The “Notwithstanding Clause,” with its explicit override of any contrary state “law, statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage,” was precisely the specific provision the Pierson court claimed was missing. The entire legal foundation of qualified immunity rests on the Court’s failure to read the authoritative version of the law it was interpreting.

B. The Ignored Legislative History

The historical record was not as opaque as the Pierson majority implied. In his powerful dissent, Justice William O. Douglas pointed directly to the legislative history of the 1871 Act, which confirmed that the 42nd Congress was perfectly aware of the statute’s broad, strict scope and enacted it over strenuous objections from its opponents.

Justice Douglas quoted directly from the debates in the Congressional Globe, where those who opposed the bill voiced their alarm that it would eviscerate traditional immunities. Mr. Arthur of Kentucky, for example, decried the bill because its provisions meant that state officials would have to “enter upon and pursue the call of official duty with the sword of Damocles suspended over him.” He complained that the bill subjected “every judge in the State court” to liability for their judicial acts.

Similarly, Senator Allen Thurman of Ohio, a leading opponent, warned that the statute was designed to ensure “that no longer a judge sitting on the bench to decide causes can decide them free from any fear except that of impeachment.” He understood, correctly, that the bill’s plain language would allow state judges to be “mulcted in damages” for decisions made “honestly and conscientiously.” His fear was that the bill would empower a federal judge to impose damages if he simply thought a state judge’s “opinion was erroneous.”

This legislative history proves two dispositive points. First, the 42nd Congress—both proponents and opponents—was fully cognizant that the statute’s plain language would impose liability on officials who had traditionally enjoyed immunity, including judges. The issue was openly and vigorously debated on the floor of Congress. Second, despite these explicit warnings about the statute’s broad sweep, Congress enacted Section 1 anyway, without adding an exception for good faith or honest mistakes. The historical record confirms what the text already makes clear: the imposition of strict liability was a feature, not a bug.

C. Harlow v. Fitzgerald and the Shift to Policy

If Pierson laid the faulty foundation for immunity, the 1982 case of Harlow v. Fitzgerald built the modern superstructure. In Harlow, the Court radically transformed the doctrine. It abandoned the subjective “good faith” standard from Pierson, which required an inquiry into an official’s personal state of mind, and replaced it with the modern, objective “clearly established law” test.

The Court’s reasoning for this shift was explicit and unapologetically grounded in judicial policymaking, not statutory text. The majority wrote at length about the need to protect officials from the burdens of litigation, expressing concern over the “social costs” involved, which it defined to include “the expenses of litigation, the diversion of official energy from pressing public issues, and the deterrence of able citizens from acceptance of public office.”

To mitigate these perceived costs, the Court created a new standard:

“Government officials performing discretionary functions generally are shielded from liability for civil damages insofar as their conduct does not violate ‘clearly established’ statutory or constitutional rights of which a reasonable person would have known.”

This move was a profound departure. The Court was no longer even pretending to interpret the statute Congress wrote. It was now openly balancing competing values and redesigning the law to achieve its preferred policy outcome: limiting litigation against government officials. This open reliance on “social costs” is the ultimate expression of the misplaced policy debate, a debate made possible only by ignoring the “lost clause.” Had the Court engaged with the original text, it would have been confronted with the fact that the 42nd Congress had already performed its own policy calculus and had concluded that the cost of unremedied constitutional violations far outweighed the cost of litigation against state officials. The “clearly established” test has no basis whatsoever in the text or history of § 1983. It is a judge-made rule created for the express purpose of protecting government officials—the very class of defendants the Reconstruction Congress had sought to hold accountable.

D. Why the Court Never Revisited the Premise

Once the Supreme Court constructed qualified immunity on the mistaken premise of congressional silence, it never meaningfully returned to test that premise against the authoritative text of the statute. This failure was not the result of a single oversight, but of an institutional dynamic that rewards doctrinal continuity over foundational reexamination. Over time, the assumption hardened into orthodoxy, and orthodoxy displaced inquiry.

The Court’s qualified-immunity jurisprudence evolved incrementally, case by case, each decision building upon the last. After Pierson v. Ray supplied the initial inference—that Congress had implicitly preserved common-law immunities—subsequent cases treated that inference as settled law. The Court cited its own precedents rather than the statute’s original text. What began as an interpretive assumption became a background axiom. Once embedded, it no longer appeared to require justification.

This phenomenon is familiar in constitutional adjudication but especially pernicious in statutory interpretation. Unlike constitutional provisions, statutes do not evolve through accretion of judicial gloss. They mean what Congress enacted until Congress amends them. Yet qualified immunity developed as if § 1983 were a common-law field, malleable to judicial recalibration in response to perceived policy concerns. The Court repeatedly refined the doctrine’s contours—first introducing a subjective good-faith standard, then abandoning it for an objective “clearly established law” test—without ever returning to the threshold question: whether any immunity doctrine was compatible with the statute Congress wrote.

Two institutional forces reinforced this drift. First, the Court’s increasing reliance on the U.S. Code as the default source of statutory text obscured the omission that gave rise to the error. As the Code supplanted the Statutes at Large in day-to-day practice, the original “Notwithstanding Clause” faded from view. The Court interpreted what it saw, not what Congress enacted. The codified silence appeared natural, and the premise it supported went unchallenged.

Second, qualified immunity produced a self-reinforcing feedback loop that insulated the doctrine from correction. Because the doctrine shields officials from liability absent factually on-point precedent, fewer cases reach merits adjudication. Fewer merits decisions mean fewer clearly established rights. That scarcity, in turn, strengthens immunity in subsequent cases. Over time, the doctrine generates the very evidentiary vacuum it requires to operate. In such an environment, there is little occasion—and even less institutional incentive—for the Court to revisit first principles.

The Court’s own framing of qualified immunity further entrenched the error. By characterizing the doctrine as a balance between competing social costs, the Court recast statutory interpretation as policy management. Questions about litigation burdens, deterrence of public service, and administrative efficiency crowded out textual analysis. Once the inquiry shifted from what Congress commanded to what the Court deemed prudent, the relevance of Reconstruction-era drafting choices diminished. The statute became a canvas for judicial optimization rather than a directive to be enforced.

Notably absent from this evolution is any sustained engagement with the hierarchy of legal authority. At no point did the Court confront the implications of interpreting a non–positive-law title as if it were controlling text, or acknowledge the significance of a clause omitted during codification but preserved in the Statutes at Large. The premise of silence survived not because it was correct, but because it was never squarely tested against the proper source of law.

This institutional inertia explains why qualified immunity persists despite mounting criticism from across the ideological spectrum. The doctrine is not merely defended on the merits; it is protected by path dependence. To revisit the premise would require the Court to acknowledge that a central feature of its § 1983 jurisprudence rests on a misreading of the statute. Such admissions are institutionally difficult, but difficulty does not confer legitimacy.

In the end, the Court’s failure to revisit the premise is not a defense of qualified immunity; it is an explanation for its endurance. Once the original text is restored to view, the doctrine’s foundation is exposed as contingent, not compelled. The question is no longer why the Court crafted qualified immunity, but why—having done so—it never returned to ask whether it had the authority to do so in the first place.

VI. Institutional Consequences: Separation of Powers and the Rule of Law

Qualified immunity is often defended as pragmatic—a doctrine said to protect governance from the burdens of litigation. But once § 1983’s enacted command is restored to view, qualified immunity’s true character becomes clear: it is not merely a screen. It is a judicial alteration of a Reconstruction statute designed to impose accountability notwithstanding state law, custom, or usage.

The consequences therefore extend beyond any single plaintiff. They implicate statutory interpretation as an institution, the separation of powers, and the rule of law. Section 1983 was crafted to make constitutional rights enforceable against state officials in federal court. Qualified immunity operates as the inverse—adding an extra-statutory prerequisite to liability that the statute’s text and historical design do not supply.

A. The False Appeal to Stare Decisis

When the textual and historical foundations of qualified immunity are challenged, the doctrine’s defenders typically retreat to a final institutional refuge: stare decisis. Even if the Court’s modern immunity regime cannot be reconciled with the Reconstruction Congress’s design, the argument goes, the doctrine has existed for decades; stability demands that it remain.

This appeal is misplaced. Stare decisis is not a constitutional license to maintain an interpretive mistake once the mistake is identified. It is a prudential doctrine intended to promote continuity in law—not to ratify an enduring conflict between enacted text and judge-made exception.

Stare decisis carries its weakest force in statutory interpretation precisely because statutes are not judicially owned. They are legislative commands. Courts do not revise them by precedent; Congress revises them by amendment. Where precedent rests on a faulty premise about what Congress enacted—particularly where that premise was generated by reliance on codified silence rather than enacted text—adhering to precedent does not promote legal stability. It promotes legal drift.

Moreover, the premise that Congress has “acquiesced” in qualified immunity is difficult to sustain. Congress has never amended § 1983 to add an immunity defense. The doctrine persists not because Congress endorsed it, but because the Court repeatedly reaffirmed it. Duration is not legitimacy. A doctrine can persist for half a century and still be wrong—especially when its persistence is the result of doctrinal path dependence rather than fidelity to statutory text.

Reliance interests do not rescue the doctrine. The Court often invokes the expectations of public officials who allegedly structure their conduct around qualified immunity. But qualified immunity does not actually operate as a behavioral guide. It operates as a litigation shield, one that is applied after the fact and often in ways no reasonable official could predict in advance. The doctrine’s “clearly established” requirement is not an operational standard of conduct; it is a retrospective clearance mechanism. If anything, it invites risk, because it teaches that novel constitutional violations can be insulated until they are repeated enough times to generate on-point precedent.

In short, stare decisis cannot be permitted to function as an immunity doctrine’s second immunity. Once the conflict between qualified immunity and § 1983’s enacted command is made plain, the question is not whether the Court has repeated the doctrine for decades. The question is whether the Court has the authority to continue enforcing a judge-made exception that contradicts a statute Congress enacted to impose liability.

B. The Separation of Powers Breach

The institutional stakes become unmistakable once qualified immunity is described in plain constitutional terms. The Constitution vests the power to enact and amend federal law in Congress, not in the judiciary. The judiciary’s duty is to interpret and apply statutes as written, not to redesign them to mitigate perceived “social costs.”

Yet that is exactly what qualified immunity represents. Beginning with Pierson and accelerating through Harlow, the Court inserted a major limitation into § 1983 that Congress did not write: an official will not be liable unless the plaintiff can show that the right was “clearly established” in a sufficiently specific and factually analogous prior case. That requirement appears nowhere in the statute. It is not an interpretation of text; it is a new condition of liability. It changes the statute’s operation in the real world from a remedial command into a narrow, precedent-gated regime.

The Court has justified this alteration by invoking policy concerns—litigation burdens, deterrence of public service, diversion of official energy, and the like. Those concerns may be legitimate matters for legislative debate. They are not legitimate grounds for judicial revision of statutory meaning. The Reconstruction Congress weighed competing consequences in its own time and reached its own conclusion: that state officials must be held answerable in federal court when constitutional rights are violated. A judiciary that disagrees with that policy judgment does not have authority to change it by doctrinal invention.

This is why the qualified-immunity debate cannot be reduced to an argument over “balance.” The real question is institutional: who decides the scope of civil-rights liability under federal law? If the answer is Congress, then the statute controls. If the answer is the Court, then § 1983 becomes a pliable instrument of judicial administration rather than a legislative command. Qualified immunity only makes sense in a legal system that permits courts to amend statutes by precedent.

That is a separation-of-powers breach. And it is magnified here because § 1983 is not a minor regulatory enactment. It is a Reconstruction statute designed to enforce the Fourteenth Amendment against state officials and hostile state systems. When courts narrow that remedy through immunity doctrines not enacted by Congress, they do more than adjust litigation incentives. They subvert the federal remedy Congress wrote to confront state resistance to constitutional rights.

C. The “Clearly Established” Feedback Loop

The most destructive institutional consequence of qualified immunity is not merely that it blocks relief in hard cases. It is that it creates a self-reinforcing system that prevents constitutional law from developing and then uses that stagnation as the justification for further immunity.

The “clearly established law” requirement purports to be a notice doctrine. In practice, it functions as a precedent scarcity doctrine. Liability is denied unless prior cases exist with sufficiently similar facts. But when courts routinely resolve cases on qualified-immunity grounds without reaching the merits, they produce fewer merits decisions. Fewer merits decisions mean fewer clearly established rights. And fewer clearly established rights mean broader immunity.

This is not an accident. It is a structural loop—one that turns the absence of precedent into a defense and then uses the defense to ensure that precedent remains absent. The result is a legal catch-22: constitutional violations may persist so long as they are not already adjudicated with sufficient factual specificity. The doctrine therefore incentivizes repetition. It permits the first violation without liability, and it makes the second violation harder to litigate if the first case was dismissed without a merit ruling.

This dynamic is the functional opposite of § 1983’s Reconstruction design. The statute was enacted precisely because constitutional rights could not be made real if enforcement depended on local willingness to hold officials accountable. Congress created a federal remedy to ensure that rights would be vindicated even when states failed to enforce them. Qualified immunity reconstructs a comparable barrier through federal doctrine: rights may be declared in principle, but they are not enforceable in practice until a court has already condemned the same conduct in a nearly identical factual setting.

This feedback loop also distorts judicial incentives. Courts are encouraged to dispose of cases quickly on immunity grounds to avoid burdensome discovery and trial, which is precisely the policy rationale the Court invoked in Harlow. But the cumulative effect is doctrinal stagnation. Constitutional law becomes trapped in abstractions while novel violations evade liability. The law does not develop because the doctrine prevents it from developing, and the doctrine remains justified because the law has not developed.

In institutional terms, this is a system that converts constitutional rights into advisory principles rather than enforceable guarantees. It creates a hierarchy in which the government’s interest in insulation from litigation burdens eclipses the individual’s interest in a remedy for constitutional injury. That inversion is not a natural outgrowth of § 1983. It is a judicial policy choice imposed onto a statute designed to do the opposite.

The conflict between § 1983 as enacted and qualified immunity as applied is not abstract or theoretical. It is structural. The two regimes operate on fundamentally incompatible premises, as the comparison below makes clear.

| Feature | The 1871 Statutory Mandate | Modern Qualified Immunity Doctrine |

| Source of Law | The text of the Civil Rights Act of 1871 (17 Stat. 13). | Judge-made common law, based on policy goals. |

| Trigger for Liability | Deprivation of a constitutional right under color of state law. | Deprivation plus violation of “clearly established” law. |

| Fault Requirement | Liability keyed to the constitutional injury itself, without a fault or intent prerequisite. | Objective reasonableness assessed through fact-specific precedent. |

| Treatment of Defenses | Express displacement of contrary state law, custom, and common-law usage. | Reconstruction of immunity defenses through federal doctrine. |

| Governing Principle | Statutory fidelity and congressional supremacy. | Judicial management of perceived “social costs.” |

Once this structural conflict is acknowledged, the qualified-immunity debate can no longer be treated as a disagreement over policy calibration or institutional comfort. It becomes a question of legal authority. A judiciary committed to the rule of law cannot continue to enforce a doctrine that rests on a misreading of a statute Congress enacted to impose liability, not to evade it. At that point, abolition is no longer a radical demand. It is the minimum requirement of statutory fidelity.

VII. Conclusion: The Path Forward is Restoration, Not Reform

For more than half a century, qualified immunity has been treated as an inevitable feature of civil-rights litigation—an embedded doctrine to be managed, refined, or cautiously adjusted at the margins. That framing is mistaken. Qualified immunity is not an interpretive gloss on § 1983; it is a judicial reconstruction of a statute that was designed to do precisely the opposite of what the doctrine now permits.

The historical and textual record leaves little room for doubt. Section 1 of the Civil Rights Act of 1871 imposed liability on any person who, under color of state law, caused the deprivation of a constitutional right. It did so notwithstanding any contrary state law, custom, or usage. That language was not accidental. It was the Reconstruction Congress’s answer to a system in which constitutional rights existed in theory but failed in practice because officials were insulated from accountability. The statute’s purpose was remedial, not aspirational. It was written to be enforced.

Qualified immunity survives only because courts have treated a codified omission as legislative silence and then built an immunity regime atop that silence. Once the authoritative text of the statute is restored to view, that foundation collapses. The premise that Congress intended to preserve common-law immunities is not merely unsupported; it is contradicted by the statute Congress enacted and by the legislative debates that accompanied it.

The path forward therefore does not lie in reforming qualified immunity, narrowing its contours, or recalibrating its tests. Those approaches accept the legitimacy of a doctrine that lacks statutory grounding. The proper course is restoration. Courts must return § 1983 to its enacted meaning and enforce it as written. Doing so does not require judicial innovation. It requires judicial restraint—the discipline to apply Congress’s command even when doing so carries institutional consequences.

This is not a choice between accountability and effective governance. It is a choice between statutory fidelity and judicial amendment. The Reconstruction Congress confronted a nation in which constitutional rights were systematically violated by state actors shielded by law, custom, and judicial habit. Its response was unequivocal. It enacted a federal remedy designed to pierce those shields and make rights enforceable in fact.

That law remains on the books. The question is not whether qualified immunity should be abolished as a matter of policy. The question is whether courts will continue to enforce a doctrine that Congress never enacted—or whether they will honor the statute Congress did.

Restoring § 1983 to its original meaning would not create new law. It would vindicate old law—law written in the shadow of civil war, enacted to confront state resistance to constitutional equality, and intended to ensure that rights promised on paper would be real in practice. The integrity of the statute, and of the judicial role itself, demands nothing less.

Reader Supplement

To support this analysis, I have added two companion resources below.

First, a Slide Deck that distills the core legal framework, case law, and institutional patterns discussed in this piece. It is designed for readers who prefer a structured, visual walkthrough of the argument and for those who wish to reference or share the material in presentations or discussion.

Second, a Deep-Dive Podcast that expands on the analysis in conversational form. The podcast explores the historical context, legal doctrine, and real-world consequences in greater depth, including areas that benefit from narrative explanation rather than footnotes.

These materials are intended to supplement—not replace—the written analysis. Each offers a different way to engage with the same underlying record, depending on how you prefer to read, listen, or review complex legal issues.