EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The New York City Police Department’s current fixation on so-called “overtime abuse” is not a belated discovery of misconduct. It is a governance maneuver. More precisely, it is an effort to launder systemic management failure through downward blame—recasting the predictable outputs of institutional design as individual moral fault.

That maneuver has a name: Selective Outrage.

Selective Outrage is how public institutions respond when long-tolerated systems become politically inconvenient. Rather than confront the architecture they designed, funded, approved, and relied upon, institutions redirect accountability toward the most expendable actors in the hierarchy—rank-and-file employees, retirees, whistleblowers, and disproportionately Black officers, Latino officers, women, and others outside traditional White-male power networks—while insulating leadership, policy choices, and structural incentives from scrutiny.

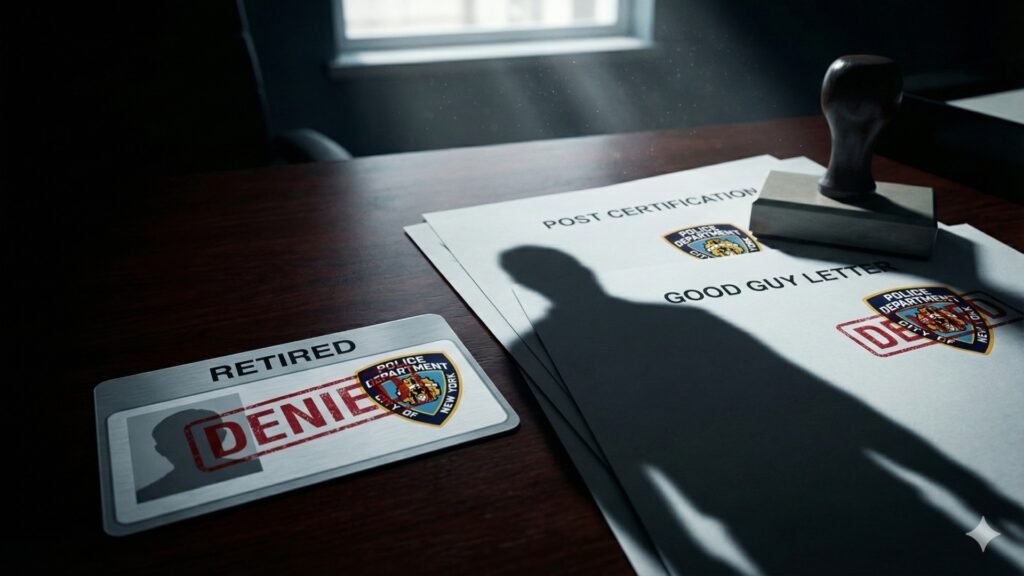

Under the current NYPD posture, Selective Outrage does not stop at rhetoric. It hardens into consequence. Credentials are delayed or denied. Certifications are questioned. Approvals are withheld. Reputations are quietly damaged. What is framed publicly as “reform” functions operationally as retaliation.

The law has rejected this strategy for decades.

Liability Flows Upward, Not Downward

The foundational principle is set out in Becker v. City of New York, where New York’s highest court made clear that institutions cannot evade responsibility for systemic failure by scapegoating employees who acted within structures management designed, tolerated, or relied upon. When conduct occurs inside an institutional system—however imperfectly—liability does not evaporate simply because leadership later regrets the outcome. It flows upward, not downward.

Becker forecloses the NYPD’s preferred post-scandal posture: the fiction that a leadership transition resets responsibility and permits retroactive moral condemnation of conduct that was previously approved, normalized, budgeted, or ignored. Institutional memory cannot be selectively erased to manufacture the appearance of reform.

The “Rogue Employee” Narrative Is a Near-Nullity

Agency law reinforces the same conclusion. In Center v. Hampton Affiliates, the Court of Appeals sharply narrowed the “rogue employee” escape hatch. An employer avoids responsibility only where an employee totally abandons the employer’s interests and acts solely for personal gain.

That standard is fatal to the NYPD’s overtime narrative.

Overtime in the NYPD exists to meet operational needs created by management decisions: chronic understaffing, unfunded deployment mandates, vacancy rates, court obligations, event policing, and command-level approvals. Where the institution benefited operationally—and where supervisors approved, forecasted, and relied upon the work—the adverse-interest exception collapses. Conduct that sustains institutional function cannot be rebranded as personal deviance without denying the institution’s own dependence on the system.

Employers Bear the Risk of the Systems They Control

Federal wage-and-hour law makes the point even more explicit. In Anderson v. Mt. Clemens Pottery, the Supreme Court rejected the oldest institutional trick in the book: employers profiting from their own recordkeeping and control failures. When an employer designs the system, controls the records, and benefits from the work, uncertainty cuts against the employer—not the worker.

Translated into the NYPD context, Anderson makes one conclusion unavoidable. An agency cannot build an overtime-dependent system, approve its outputs, rely on its flexibility, and then declare those outputs “abuse” once they become politically embarrassing.

Structural Failure Cannot Be Rebranded as Misconduct

New York law echoes the same warning. In Matter of Mid-Hudson Pam Corp. v. Hartnett, courts rejected employer narratives that attempted to recharacterize structural and managerial failures as individual wrongdoing—particularly where enforcement activity, wage claims, or resistance to the employer’s narrative triggered retaliation.

Mid-Hudson Pam matters here because the NYPD’s overtime crackdown is not occurring in isolation. It is unfolding alongside credential delays, disciplinary investigations, and paper-based sanctions that disproportionately fall on those who challenge the narrative, separate from service, enforce their rights, or simply lack institutional protection.

“Paper” Decisions as Punishment

The modern warning flare appears in Perros v. County of Nassau. There, the Eastern District of New York confronted what agencies prefer to dismiss as trivial: the withholding of credentials. The court found that denying “good guy” letters to disabled retirees functioned as punishment with real-world consequences—humiliation, reputational injury, employability harm, and safety risk. The court awarded compensatory damages against the County and punitive damages against the former Sheriff.

Perros exposes what institutions avoid saying out loud. These so-called administrative or “paper” decisions are not neutral. They operate as scarlet letters. They are discipline by other means, designed to punish without due-process visibility and to chill dissent, separation, and enforcement activity.

Judicial Skepticism of Optics-Driven “Reform”

Recent cases—including Chislett—signal growing judicial skepticism toward post-scandal “reform” that looks less like accountability and more like retaliation. Courts are increasingly unwilling to accept the premise that retroactive discipline equals progress, particularly where it is untethered from contemporaneous rules, selectively enforced, and disproportionately imposed on disfavored employees.

The Through-Line

Taken together, these decisions articulate a single, consistent legal message:

Institutions cannot profit from systems they designed and then disown those systems through moral outrage.

Liability flows upward when employees act within tolerated or encouraged structures.

The “rogue employee” narrative fails where the institution benefited.

Recordkeeping and control failures cannot be weaponized against workers.

Credential denial and reputational sabotage are materially adverse actions—not neutral administration.

And retaliation disguised as reform increasingly attracts judicial condemnation.

This thought-piece applies those principles to the NYPD’s current overtime narrative and its expanding use of credential-based retaliation—POST certification interference, Good Guy letters, identification cards, and related gatekeeping—as tools of selective enforcement.

The question is not whether the NYPD needs reform. It does.

The question is whether reform will be structural—or whether the Department will continue to practice Selective Outrage: punishing compliance with yesterday’s rules to protect the architects of those rules today.

The law has already answered that question.

The institution simply refuses to listen.

I. Introduction: From “Overtime Abuse” to Institutional Panic

Selective outrage rarely ends with rhetoric. Public institutions do not manufacture moral crises merely to express disapproval; they do so to justify consequence. Once conduct is rebranded as “abuse,” punishment becomes reframed not as retaliation but as reform. Credentials are withheld, approvals are delayed, letters are denied, certifications are revoked—not because the conduct suddenly became unlawful, but because the narrative surrounding it has been rewritten. This is the transformation institutions prefer not to name: when outrage hardens into discipline, selective outrage acquires its second name. It becomes retaliation.

The New York City Police Department’s sudden fixation on “overtime abuse” is not the product of discovery. It is the product of institutional panic, carefully staged and politically choreographed under the banner of reform. Panic emerges when an institution is forced to confront the political consequences of systems it designed, normalized, and relied upon for years—but lacks the will to confront those systems honestly. In such moments, accountability is not eliminated; it is redirected.

This redirection now operates under the public-facing image of the Tisch administration, which has been marketed aggressively as a break from the past: technocratic, disciplined, data-driven, and morally corrective. The narrative is seductive. A “reformer” arrives. Order is restored. Excess is purged. The institution cleanses itself.

But symbolism is not structure. And what is being sold as reform is, in reality, political theater.

Overtime at the NYPD did not metastasize in the dark. It was not a rogue phenomenon tolerated by inattentive leadership. It was an open, budgeted, and institutionally indispensable mechanism through which the Department reconciled chronic understaffing, expanding deployment mandates, and relentless political pressure to project control without funding it. Overtime was not merely permitted; it was relied upon. It allowed City Hall to promise omnipresence without paying for it and allowed senior leadership to meet performance metrics without confronting institutional limits.

For years, this reality was not contested. Commanders approved overtime as routine. Budget offices forecasted it. Payroll processed it. Deployment models assumed it. The Department functioned on the shared understanding that without overtime, its operational commitments would collapse.

What changed was not the system. What changed was the political narrative.

The arrival of the Tisch administration coincided with a need for reputational reset. The NYPD did not require structural reform so much as optical redemption. The “overtime abuse” narrative supplied the perfect vehicle. It allowed the Department to announce discipline without admitting design failure, to perform accountability without touching leadership decisions, and to satisfy media demand for villains without implicating policy.

This is the essence of Selective Outrage.

Selective Outrage is not accidental. It is a governance strategy deployed when institutions need to protect themselves from their own history. It works by collapsing systemic outcomes into individualized moral failure. The institution disappears from the story; the employee becomes the problem.

Under the Tisch administration, this strategy has been refined and legitimized through the language of modernization and reform. Data dashboards replace historical memory. Managerial vocabulary replaces institutional responsibility. And “abuse” replaces architecture.

But this outrage is not evenly distributed.

Within the NYPD, Selective Outrage has always tracked power, race, and gender. When institutional systems disproportionately benefited White male officers embedded within favored units, legacy command networks, or politically insulated hierarchies, the response was accommodation. Rules were quietly rewritten. Expectations were recalibrated. Practices were justified as “meeting the needs of the Department.”

When those same systems appear to benefit Black officers, Latino officers, women, or others outside the Department’s traditional power core, the tone shifts. Silence becomes suspicion. Accommodation becomes investigation. Structural necessity becomes moral condemnation. The conduct does not materially change; the identity of the beneficiary does.

This asymmetry is not incidental. It is the mechanism by which institutions preserve hierarchy while claiming neutrality. Selective Outrage allows leadership to say, “We are restoring integrity,” while quietly reinforcing who is presumed legitimate and who is perpetually suspect.

The Tisch administration’s “savior” narrative depends on this asymmetry. Reform requires contrast. To appear corrective, the present must be framed as disciplined against a morally deficient past. Overtime becomes the symbol of that deficiency—not because it newly emerged, but because it can be weaponized rhetorically. The Department does not explain why overtime was necessary. It declares that it was abused. And once abuse is declared, punishment becomes not only permissible but inevitable.

This is how political theater substitutes for structural reform.

The danger of this substitution is profound. By moralizing the outputs of institutional design, the NYPD avoids confronting the drivers of overtime altogether: chronic understaffing, unfunded mandates, politically imposed deployments, and performance metrics untethered from capacity. Those drivers remain intact. The system remains unchanged. Only the narrative shifts.

And that shift carries consequences.

Employees learn that compliance with yesterday’s rules offers no protection against today’s condemnation. Supervisors learn that approvals given in good faith may later be reclassified as negligence. Officers of color and women—already navigating conditional legitimacy—learn that visibility itself can become liability. The message is unmistakable: institutional memory is selective, and protection is hierarchical.

Selective Outrage thus performs a dual function. It reassures the public that reform is underway, while signaling internally that power remains insulated. Leadership is absolved. Architecture is untouched. Accountability is displaced downward.

This thought-piece proceeds from the premise that the law does not permit this maneuver, no matter how carefully it is staged. Courts have repeatedly rejected attempts by institutions to profit from systems they designed and then disown those systems through retrospective moral judgment. The doctrine is settled. What remains unsettled is whether the NYPD, under the Tisch administration, will continue to treat reform as theater—or confront the legal and structural consequences of its own design choices.

II. Overtime Is a System, Not a Vice

Overtime at the New York City Police Department is not a behavioral anomaly. It is not a moral lapse. It is not a vice indulged by a few bad actors. It is a systemic output, produced predictably and repeatedly by institutional design choices that predate any individual officer, supervisor, or administration—including the current one.

To describe overtime as “abuse” is therefore not merely inaccurate. It is conceptually dishonest.

The NYPD is the largest municipal police force in the United States, charged with maintaining continuous coverage across a city of more than eight million people. That mission has never been resourced in proportion to its scope. Chronic understaffing is not episodic; it is structural. Patrol strength has declined even as deployment expectations have expanded. Specialized units proliferate while precinct-level staffing thins. Political leaders demand omnipresence—on subways, at protests, in nightlife corridors, around sensitive infrastructure—without funding the personnel required to meet those demands within standard tours.

Overtime is how that gap has been bridged for decades.

This is not conjecture. Deployment mandates routinely exceed scheduled staffing. Emergency conditions are declared with regularity. Planned events become “unplanned” overtime sinks. The result is predictable: supervisors authorize overtime to meet command expectations, and officers accept it to comply with orders and maintain coverage. Payroll systems process it. Budget offices anticipate it. Year after year, overtime is not treated as aberrational—it is treated as inevitable.

The key point is control.

Individual officers do not control staffing levels. They do not determine deployment mandates. They do not design tour structures, authorize minimum headcounts, or set performance benchmarks. Those decisions are made at the command, bureau, and executive levels—often in direct response to City Hall pressure. To later describe overtime as “abuse” by those subject to these decisions is to invert reality.

Yet that inversion is precisely what Selective Outrage requires.

Once overtime is reframed as moral failure rather than structural necessity, the institution can disown its own architecture. The same approvals that were once routine become suspect. The same conduct that was once praised as dedication becomes recast as greed. The narrative shifts from how did this system require so much overtime to who took too much.

This rhetorical maneuver is not neutral. It is downward-facing by design.

And it is not applied evenly.

When overtime disproportionately benefited White male officers embedded within favored units, legacy command networks, or politically insulated hierarchies, it was normalized. Rules were bent. Caps were ignored. Internal adjustments were made quietly to “meet operational needs.” The system accommodated itself.

When overtime patterns appear to benefit Black officers, Latino officers, women, or others outside the NYPD’s traditional power core, accommodation gives way to scrutiny. Silence gives way to investigation. Structural necessity becomes individualized suspicion. The numbers do not suddenly change—the identity of the beneficiary does.

This is not conjectural; it is institutional muscle memory.

Overtime, like promotion, discipline, and credentialing, has always functioned as a proxy through which the Department signals who belongs and who remains provisional. Selective Outrage transforms neutral metrics into moral judgments precisely when those metrics threaten the existing hierarchy.

The Tisch administration’s framing of overtime “abuse” fits squarely within this pattern. Marketed as technocratic reform, it relies heavily on data visualization and managerial language to create the appearance of objectivity. But data does not interpret itself. Someone decides what constitutes excess, which timeframes matter, which comparators are relevant, and which contextual factors are ignored.

Those decisions are political.

By focusing on outcomes rather than inputs, the Department avoids uncomfortable questions: Why were these deployments required? Why were staffing levels insufficient? Why were supervisors approving this overtime repeatedly? Why did budget forecasts anticipate it? These questions implicate leadership, not line officers.

Selective Outrage answers those questions by refusing to ask them.

The danger of post-hoc moralization is not only unfairness; it is instability. When institutions retroactively condemn conduct they previously relied upon, they erode trust in governance itself. Officers learn that compliance offers no protection. Supervisors learn that approvals given in good faith may later be reclassified as negligence. Entire classes of employees—particularly those already subject to conditional legitimacy—learn that visibility itself can become liability.

This is the environment in which retaliation flourishes.

Once overtime is rebranded as abuse, punishment must follow to validate the narrative. Discipline becomes proof of reform. Credentials become leverage. Administrative actions that once would have been unthinkable are reframed as necessary housekeeping. The system demands consequence, not because the conduct changed, but because the story did.

That is why overtime cannot be analyzed as conduct in isolation. It must be understood as institutional output, and any attempt to punish individuals for producing that output necessarily implicates retaliation. The law has long recognized this principle, even when institutions pretend otherwise.

Which brings us to Becker.

III. Becker v. City of New York: The Prohibition on Downward Accountability

Becker v. City of New York stands for a principle that institutions repeatedly test and courts repeatedly reaffirm: liability flows upward when employees act within systems created, authorized, or tolerated by management. The case is not merely about agency law; it is about institutional honesty.

Becker rejects the convenient fiction that organizations can reap the benefits of a system while disowning responsibility for its consequences. When an institution designs a structure, tolerates its operation, and benefits from its outputs, it cannot later cleanse itself by blaming the individuals who functioned within that structure.

This doctrine is devastating to Selective Outrage.

In Becker, the City attempted to distance itself from the conduct of its employees by characterizing their actions as unauthorized or excessive. The court rejected that framing, recognizing that formal limits on authority do not sever institutional responsibility where the conduct occurred within the scope of employment and advanced institutional interests. Acting beyond precise formal authority does not erase the reality of structural permission.

That holding matters profoundly in the NYPD overtime context.

Officers did not invent overtime. Supervisors did not invent the need for it. The Department designed tour structures that made overtime inevitable, imposed deployment mandates that required it, and approved it repeatedly over time. Even where individual approvals may have exceeded nominal thresholds, the system itself depended on those approvals to function.

Under Becker, the NYPD cannot retroactively declare that dependency illegitimate and punish those who satisfied it.

This is particularly true following leadership transitions. Institutions often attempt to draw a bright line between “then” and “now,” portraying new administrations as untainted reformers confronting inherited dysfunction. Becker forecloses that maneuver. An institution does not reset its legal obligations by changing leadership or rebranding itself. Continuity of structure defeats claims of discontinuity of responsibility.

The Tisch administration’s reform narrative runs directly into this wall.

By casting overtime as “abuse,” the Department implicitly asserts that prior practices were improper. But Becker makes clear that if those practices were tolerated, approved, and operationally beneficial, responsibility cannot be shifted downward after the fact. To do so is not reform—it is scapegoating.

And scapegoating, when coupled with adverse consequences, becomes retaliation.

The significance of Becker extends beyond overtime. It establishes a broader prohibition against downward accountability masquerading as discipline. Institutions may discipline for genuine misconduct. They may not punish employees for complying with systems the institution itself designed or relied upon, particularly when those systems disproportionately impacted disfavored groups.

When Black officers, Latino officers, women, or others outside traditional power networks are targeted under a narrative of reform for conduct long tolerated—and often encouraged—the inference of retaliatory motive strengthens. Becker supplies the doctrinal backbone for that inference.

Crucially, Becker also dismantles the “rogue employee” trope before it can be deployed. The City cannot argue that individual actors wholly departed from institutional interests when the institution benefited from their actions. Overtime ensured coverage. Coverage satisfied political demands. Political satisfaction preserved leadership. The benefit chain is unbroken.

Once that chain is acknowledged, punishment can no longer be framed as neutral enforcement. It becomes what it is: an effort to launder systemic failure through individual consequence.

That laundering is precisely what the law forbids.

Becker thus performs a dual function in this analysis. It clarifies responsibility, and it exposes pretext. It reminds courts—and institutions—that reform does not authorize amnesia, and that leadership transitions do not license retroactive blame.

When applied to the NYPD’s current posture, Becker leads inexorably to the conclusion that disciplining employees for overtime generated by institutional design is not accountability. It is retaliation dressed as reform.

And once retaliation is understood as the legal name for Selective Outrage, the remaining cases—Center, Anderson, Mid-Hudson Pam, Perros, and Chislett—fall into place not as anomalies, but as confirmation.

IV. Center v. Hampton Affiliates: Why the “Rogue Employee” Narrative Fails

When the NYPD describes overtime as “abuse,” it is not merely condemning conduct — it is telling a story. That story is essential to the Department’s current political survival, particularly under an administration marketed as reformist. The story is simple, familiar, and dangerously effective: a few bad actors exploited the system; management intervened; integrity was restored. In this telling, the institution is cast as victim, rescuer, and moral authority all at once.

But Center v. Hampton Affiliates, Inc. stands as a direct legal rejection of that narrative architecture.

Center addresses a doctrine institutions routinely weaponize when scandal threatens to climb upward: the “adverse interest” exception. Employers invoke it to argue that misconduct by employees should not be imputed to the institution because the employee allegedly acted against the employer’s interests. But the Court of Appeals made unmistakably clear that this exception is extraordinarily narrow. It applies only where the employee has totally abandoned the employer’s interests and acted entirely for personal gain. Partial benefit to the employer — even if coupled with wrongdoing — destroys the exception.

This is fatal to the NYPD’s “rogue employee” framing of overtime.

Overtime at the NYPD does not occur in a vacuum. It exists because the Department is chronically understaffed, politically over-tasked, and required to project omnipresence without commensurate funding. Overtime fills that gap. It keeps patrol cars staffed, demonstrations policed, details covered, crime statistics politically manageable, and City Hall insulated from the consequences of underinvestment. When officers work overtime — whether excessive, poorly monitored, or aggressively pursued — the NYPD benefits operationally. That benefit is not incidental; it is the point.

Under Center, that operational benefit collapses the adverse-interest defense entirely.

The Department cannot plausibly claim that officers who worked overtime abandoned the NYPD’s interests when that overtime allowed the Department to meet deployment mandates it otherwise could not meet. Nor can it argue that supervisors who approved overtime acted against institutional interests when those approvals were necessary to satisfy performance metrics and political expectations. The conduct may later be characterized as “mismanaged,” but mismanagement is not abandonment. Reliance is not betrayal.

This distinction matters because Selective Outrage depends on erasing it.

The NYPD’s overtime panic did not arise because the Department suddenly discovered a moral violation. It arose because overtime became politically inconvenient — expensive, visible, and rhetorically useful as a symbol of disorder under prior leadership. The arrival of the Tisch administration created a demand for contrast. A “savior” narrative requires a sinful past. Overtime was rebranded to supply that past.

But Center refuses to let institutions rewrite history by isolating individuals from systems. If the system produced a predictable output that benefited the institution, the institution cannot wash its hands by pointing downward.

This is where race and power enter the analysis — not as rhetoric, but as evidence.

Historically, when overtime practices disproportionately benefited White male officers embedded in favored units, legacy commands, or politically protected hierarchies, the NYPD’s response was accommodation. Rules were informally bent. Oversight was lax. Practices were justified as “meeting operational needs.” Silence reigned.

When those same overtime practices visibly benefited Black officers, Latino officers, women, or others outside the Department’s traditional power core, silence gave way to scrutiny. Scrutiny hardened into suspicion. Suspicion hardened into moral condemnation. The conduct did not materially change. The identity of the beneficiary did.

Selective Outrage operates precisely at this inflection point. It allows the institution to declare neutrality while enforcing hierarchy. It allows leadership to say “we are restoring integrity” while ensuring that accountability never reaches those who designed, approved, and relied upon the system itself.

Center forecloses that maneuver doctrinally. It asks not whether the employee followed every rule, but whether the employer benefited. And if the employer benefited — operationally, politically, reputationally — the employer cannot pretend the conduct was foreign to its interests.

This has particular force in the public-sector context. The NYPD is not a private enterprise stumbling upon hidden misconduct. It is a command-and-control institution with layered supervision, formal approvals, payroll systems, audits, and data analytics. Overtime does not materialize spontaneously. It is requested, approved, recorded, and paid. To describe that process as “rogue” is not merely inaccurate; it is disingenuous.

And disingenuousness becomes retaliation when it is operationalized.

Once the “rogue employee” narrative is accepted, the institution gains moral cover to impose consequences that would otherwise appear punitive. Credentials can be delayed. Letters can be denied. IDs can be withheld. Careers can be stalled — all under the guise of reform. Center strips away that cover by insisting that institutions remain accountable for the systems they profit from, even when they later regret the optics.

In short, Center is not a technical agency case. It is a warning. Institutions do not get to launder systemic dependence through individualized blame. When they try, the law is prepared to follow the benefit — and the responsibility — upward.

V. Wage-and-Hour Law Rejects Institutional Gaslighting

The NYPD’s “overtime abuse” storyline is not merely a disciplinary posture; it is a legal strategy disguised as moral commentary. It attempts to convert a management-designed system into an employee-created vice, and then to justify “reform” by punishing the people who lived inside the structure rather than the people who built, approved, and relied on it. Wage-and-hour doctrine—federal and New York—has spent nearly a century rejecting this exact maneuver. It rejects it not because employers may never discipline fraud, but because institutions may not profit from their own control failures and then pretend those failures are proof of worker wrongdoing.

That is the core insight of Anderson v. Mt. Clemens Pottery Co. Overtime controversies are often framed as disputes about numbers—how much time, how many hours, what documentation. Anderson reframes the inquiry as a dispute about power and information. The Supreme Court recognized what employers prefer not to say out loud: the employer controls the workplace, the rules of timekeeping, the supervisory chain, and the recordkeeping system. When that system produces uncertainty, the law does not allow the employer to weaponize that uncertainty against the worker. Instead, once an employee shows work performed with evidence sufficient to support a “just and reasonable inference,” the burden shifts to the employer to negate that inference. The employer may not defeat liability by pointing to the very record defects it created or tolerated.

The institutional logic is simple and devastating: recordkeeping failures are not neutral accidents; they are governance failures, and governance failures do not become worker blame.

Apply that to the NYPD’s overtime structure. The Department’s overtime is not generated by isolated decisions by officers at the bottom of a hierarchy. It is the predictable output of chronic understaffing, deployment mandates imposed by City Hall and the Commissioner’s office, and command-level approvals embedded in the Department’s daily machinery. Payroll systems process overtime. Supervisors approve it. Commanders depend on it to keep posts filled. Budget offices forecast it. Performance metrics assume it. The Department has historically treated overtime as a substitute for hiring, a method for meeting coverage demands without confronting political resistance to full staffing. In other words, overtime is not a hidden glitch; it is a structural feature.

That is precisely why the “abuse” label is so useful to political theater and so incompatible with wage-and-hour doctrine. Once overtime is moralized as “abuse,” the institution gains the rhetorical right to punish, even if it cannot truthfully claim it was blind to the underlying architecture. “Abuse” is the language that converts predictable outputs into individualized misconduct, and individualized misconduct is the narrative bridge to retaliation.

New York’s administrative wage enforcement reinforces the same principle. Matter of Mid-Hudson Pam Corp. v. Hartnett stands for more than the proposition that employers must maintain lawful records and pay wages owed. It reflects New York’s refusal to entertain employer storytelling designed to recharacterize structural failures as employee wrongdoing. When recordkeeping is defective, New York enforcement does not treat that defect as a mere procedural inconvenience; it treats it as the employer’s problem. And critically, the case law and enforcement framework reject an employer’s attempt to obscure its own statutory noncompliance by reframing the worker as the wrongdoer for accepting wages for time the employer’s system permitted, demanded, or knowingly allowed.

This is what I mean by institutional gaslighting: the process by which management claims the outputs of its own system are evidence of employee moral failure, and then sells discipline as reform.

The NYPD’s current posture echoes that pattern. For years, overtime was treated as operational necessity. Commanders approved it because the Department would not function without it. Senior leadership benefited from it because it allowed the Department to project capacity beyond its funded headcount. City Hall benefited because overtime postponed the political cost of staffing honesty. And the media ecosystem benefited because it could celebrate “results” without asking how the results were financed.

What changed was not the operational reality. What changed was the political utility of outrage.

Under the Tisch administration, “overtime abuse” became a narrative vehicle for reputational reset. It provided an easy contrast with prior leadership, an easy set of villains, and an easy way to perform accountability without confronting the structural decisions that created overtime dependency in the first place. That is why the Tisch “reformer” brand matters here. A savior narrative requires a sin. Overtime becomes that sin, not because it suddenly emerged, but because it can be rhetorically weaponized.

And this is where the Selective Outrage framework becomes legally consequential: the outrage is not evenly distributed.

Within the NYPD and similar agencies, institutional accommodation has historically followed power. When overtime patterns disproportionately benefited White male officers embedded within favored units, legacy networks, or politically insulated command structures, the response was often selective silence—rules recalibrated quietly, practices justified as “meeting the needs of the Department,” and enforcement treated as discretionary. When those same patterns appeared to benefit Black officers, Latino officers, women, and others outside the Department’s traditional power core, the vocabulary shifted: suspicion replaced accommodation, and “integrity” replaced operational necessity.

Wage-and-hour doctrine does not use the phrase “selective outrage,” but it polices the same behavior: post-hoc moralization and downward blame. It insists that institutions cannot treat time worked as optional because the optics changed, and cannot convert management dependence into worker misconduct simply because a new administration needs to project discipline.

The central warning of Anderson and Mid-Hudson Pam is therefore structural: when the employer controlled the system, the employer owns the consequences. Where the NYPD attempts to turn system outputs into individualized sin, wage-and-hour law supplies the rebuttal: the institution bears the burden of its own design, supervision, and recordkeeping choices. Anything else is not reform. It is narrative laundering—often followed, predictably, by retaliation.

VI. From Discipline to Retaliation: When “Reform” Crosses the Line

Selective outrage does not end at rhetoric. It is a pipeline. Institutions manufacture a moral crisis not to describe reality, but to justify consequence. Once conduct is rebranded as “abuse,” punishment becomes reframed not as retaliation but as reform. This is the institutional alchemy that matters most in the NYPD’s current moment: outrage hardens into discipline; discipline migrates into credential control; and credential control becomes the modern mechanism of retaliation.

This section is where the thesis becomes operational: Selective Outrage has a second name—Retaliation.

Retaliation doctrine exists because institutions rarely announce what they are doing. They do not say, “We are punishing you for speech,” or “We are punishing you for complaining,” or “We are punishing you for separating from service.” They say “review.” They say “procedure.” They say “administrative discretion.” They say “integrity.” In public employment, the most effective retaliation is often the kind that looks mundane on paper but is catastrophic in practice: delays, denials, holds, credential interference, and reputational signaling.

The NYPD is structurally suited for this form of retaliation because it controls the very instruments that determine post-employment dignity, safety, and economic mobility. “Reform” can be staged through paperwork while leadership remains insulated from accountability. The question is not whether any agency may regulate credentials; it is whether credentials are being used as a punitive lever to enforce loyalty, punish disfavored groups, and rewrite history through discipline.

Here is what credential retaliation looks like in the NYPD context—specifically the mechanisms you have emphasized as materially adverse actions in modern public employment:

1) Revocation or delay of POST-related standing or equivalent certifications.

In any law-enforcement-adjacent labor market, certification functions like employability. It is not a plaque; it is access to future work in security, training, investigations, consulting, and public-sector roles that require proof of standing. When a department delays, questions, or obstructs the issuance of certification, it constricts the employee’s economic future while maintaining plausible deniability: “It’s under review.” That phrase is often the retaliation.

2) Denial of “good guy” letters (or analogous recommendation credentials).

The label is deceptively informal; the consequence is not. A recommendation letter is a reputational passport within law enforcement culture. Its absence is not neutral; it is an insinuation. It communicates suspicion to licensing officials, employers, and other agencies. In a system where credibility and perceived trustworthiness are currency, denial operates as punishment. Even delay can function identically, because opportunity windows close.

3) Refusal to issue or renew police identification cards and retirement credentials.

This is where retaliation becomes both symbolic and dangerous. Credentials are not mere memorabilia. They are safety mechanisms and professional identity documents. Refusal to issue them is a way to signal disgrace, to impose humiliation, and to destabilize a retiree’s standing in encounters with law enforcement and employers. It is also a method to punish separation itself—to teach employees that leaving is treated as dissent.

These acts are not accidental side effects. They are governance tools, particularly in a department that has long treated “integrity” language as a mechanism of control. And once the Department has publicly moralized an issue like overtime, credential control becomes the cleanest way to produce visible consequences without litigating the uncomfortable question: who designed and depended on the overtime system in the first place?

This is why the Tisch administration’s “reformer” branding matters substantively, not just rhetorically. A technocratic savior narrative requires performance. Performance requires targets. Targets are rarely chosen by neutral principle; they are chosen by political convenience. Overtime provides a perfect pretext because it is numeric, headline-friendly, and easily moralized. “Abuse” is a convenient word because it permits punishment without admitting structural dependence.

But the Selective Outrage framework requires the next step: who gets targeted, and who gets insulated.

In the NYPD, selective enforcement has repeatedly mapped onto race, gender, and proximity to institutional power. When practices advantaged White male officers embedded in favored networks, management often found ways to normalize and accommodate those practices as “operational needs.” When similar practices visibly benefited Black officers, Latino officers, women, and others outside the traditional power core, scrutiny intensified and moral condemnation followed. The same institutional outputs were treated as evidence of competence or corruption depending on the identity of the beneficiary.

That is not merely unfair; it is legally consequential because retaliation claims and equal protection claims often turn on comparative evidence—who was treated differently, under what conditions, and with what institutional explanations. When the NYPD applies moral language selectively, it strengthens the inference that enforcement is not neutral reform but discipline directed downward to protect leadership and preserve hierarchy.

And retaliation doctrine does not require a firing to be actionable. The modern standard focuses on whether the conduct would deter a reasonable person from engaging in protected activity—complaining, reporting, participating in investigations, refusing unlawful orders, or simply separating from service. Credential denial and credential delay are textbook deterrence mechanisms because they threaten the employee’s future while preserving the employer’s cover story.

The operational consequence is chilling. Officers learn that compliance with yesterday’s rules can be rebranded as misconduct tomorrow. Supervisors learn that approvals given in good faith may be recast as negligence when the political winds shift. Officers of color and women—already subject to conditional legitimacy—learn that being visible can become a liability. And anyone considering whistleblowing learns the real cost is not always immediate termination; it is administrative suffocation.

That is how “reform” crosses the line. Not through dramatic announcements, but through the quiet conversion of discretionary administrative processes into punitive levers. The institution claims it is restoring integrity. In reality, it is enforcing loyalty and redistributing blame away from the architects of the system.

If Selective Outrage is the narrative stagecraft, retaliation is the enforcement mechanism. And the more effectively outrage is marketed—especially under a “savior” administration—the more likely retaliation can be sold as discipline, discipline as reform, and reform as progress.

That is the institutional trick. This thought-piece is designed to strip it of its camouflage.

VII. Perros v. County of Nassau: Retaliation Made Visible

Institutions often insist that retaliation is too blunt a concept to describe what they are doing. They prefer softer language—administrative discretion, process, review, compliance. What Perros v. County of Nassau, 2025 WL 2533586 (E.D.N.Y. Sept. 3, 2025), makes unavoidable is that these euphemisms collapse the moment form is separated from function. The case does not merely award damages. It exposes, with unusual clarity, how “paper decisions” operate as punishment, stigma, and deterrence—precisely the mechanism now being normalized within the NYPD under the banner of reform.

The factual posture of Perros appears narrow only if one ignores institutional context. Former law-enforcement officers—many disabled in the line of duty—were denied so-called “good guy” letters by the Nassau County Sheriff. On paper, the letters were discretionary recommendations. In practice, they were gatekeeping devices that determined whether a retiree could lawfully possess a firearm, retain professional standing, or move through the world without visible markers of disfavor. Without the letter, retirees were required to surrender personal weapons, issued identification cards that visibly marked them as suspect, and deprived of the reputational closure that law-enforcement service traditionally confers.

Judge Brown refused to accept the fiction that this was neutral administration.

The opinion treats discretion with the seriousness it deserves: not as a talisman against liability, but as a tool whose use reveals motive. The court recognized that the denials were systematic, not incidental; targeted, not random; and driven by animus toward disabled retirees who departed on terms the institution resented. The result was not inconvenience but harm—humiliation, reputational injury, and tangible safety risk. Compensatory damages were imposed against both the County and the former Sheriff. Punitive damages were imposed against the Sheriff personally. The message was unmistakable: when discretion is used to punish, it is retaliation, regardless of the label attached.

This matters for the NYPD because Perros dismantles the Department’s most reliable shield—the claim that credential control is merely administrative housekeeping.

Within the NYPD, credentials are not symbolic. They are currency. “Good guy” letters, POST certifications, retirement IDs, and related approvals determine employability, safety, and social standing inside and outside law enforcement. To interfere with those credentials is to impose consequence. The Department understands this intuitively, which is why such tools are so effective as instruments of discipline without due process.

Perros makes explicit what agencies prefer to keep implicit: that credential denial functions as a scarlet letter.

The opinion also rejects a second fiction central to selective outrage—that harm must be economic to be legally cognizable. The court credited testimony about humiliation, stigma, and fear. It recognized that reputational injury in law enforcement is not abstract; it is operational. A retired officer marked as disfavored is not merely embarrassed; they are exposed. That recognition is devastating to agencies that rely on the idea that “nothing happened” because no paycheck was docked.

The parallels to the NYPD are immediate.

Under the current “overtime abuse” narrative, the Department has created conditions in which administrative tools are poised to become punitive ones. Officers whose overtime was previously approved, forecasted, and relied upon now face retroactive scrutiny. Supervisors who signed off in accordance with longstanding practice face second-guessing. And those most vulnerable to this shift—Black officers, Latino officers, women, and others outside the Department’s traditional power core—are disproportionately exposed once outrage demands consequence.

Perros teaches that when consequence flows from narrative rather than rule, retaliation is no longer speculative. It is inferable.

The case is also instructive in its treatment of separation. The harm in Perros was triggered not by misconduct but by the manner of departure—disability retirement. The message was clear: exit on our terms, or pay the price. That logic mirrors what is emerging within the NYPD, where separation, whistleblowing, or even visibility can trigger administrative hostility disguised as integrity enforcement.

Most importantly, Perros confirms that courts will not allow institutions to hide behind discretion when discretion is wielded as punishment. The decision places the burden where it belongs—on the institution to explain why its discretionary choices align with legitimate governance rather than retaliatory motive.

For the NYPD, the warning is stark. Credential control cannot be used to validate a reform narrative without exposing the Department to liability. Once outrage hardens into administrative consequence, selective outrage acquires its second name. It becomes retaliation.

VIII. Monell Liability and Credential Weaponization

If Perros exposes retaliation at the ground level, Monell explains why institutions cannot escape liability by pretending that retaliation is aberrational. Municipal liability exists precisely to prevent the maneuver now unfolding within the NYPD: laundering systemic failure through individualized punishment while insulating leadership and architecture from scrutiny.

Under Monell v. Department of Social Services, a municipality is liable when constitutional injury results from official policy, custom, or the acts of a final policymaker. What agencies routinely misstate—and what courts increasingly emphasize—is that policy does not require a written directive. Policy can be proven through pattern, practice, selective enforcement, or deliberate indifference. When retaliation becomes a method, it becomes policy.

Credential weaponization fits squarely within this framework.

The NYPD maintains centralized control over critical credentials: certifications, recommendations, identification cards, and post-employment approvals. That control is intentionally opaque. Decisions are slow, discretionary, and poorly documented. This opacity is not accidental; it allows discipline to occur without explanation and deterrence to operate without accountability. When such tools are deployed selectively, they cease to be administrative. They become instruments of governance.

Selective outrage supplies the justification. Credential control supplies the enforcement.

When the Department announces an “overtime abuse” crisis, it creates political demand for consequence. Leadership cannot discipline itself without admitting design failure. Architecture cannot be punished without restructuring. Credentials, however, can be delayed, denied, or revoked quietly. The institution appears disciplined. The hierarchy remains intact.

That is the Monell problem.

When credential interference follows leadership messaging rather than contemporaneous rulemaking, it suggests pretext. When it disproportionately affects Black officers, Latino officers, women, or those perceived as disloyal, it evidences discriminatory custom. When supervisors understand—implicitly or explicitly—that credentials are how “problems” are handled, the practice becomes institutional knowledge. At that point, the municipality owns it.

The NYPD’s command structure only strengthens this inference. Authority over credentials flows upward, not outward. Decisions are centralized. Appeals are limited. When senior leadership tolerates or encourages the use of credential delay as discipline, that tolerance is itself policy.

Perros illustrates how easily such conduct is traced back to policymaker authority. The Sheriff was a final decision-maker; his animus was the County’s animus. The NYPD’s hierarchy is even more consolidated. When credential interference aligns with executive rhetoric about reform and integrity, the link to policy is not subtle.

Monell also forecloses the defense that discipline is neutral because discretion exists. Discretion does not absolve selective enforcement. In fact, selective enforcement is how discriminatory policy most often manifests. When similarly situated employees are treated differently based on race, gender, or perceived loyalty, discretion becomes evidence, not insulation.

Credential weaponization also solves a political problem for institutions: it allows reform to be performed backward. Instead of changing rules prospectively, the Department punishes compliance with yesterday’s architecture under today’s narrative. That inversion is precisely what Monell exists to prevent. Municipalities may not discipline away their own exposure.

For the NYPD, the implication is unavoidable. If overtime was systemically approved, forecasted, and relied upon, then post-hoc punishment framed as integrity enforcement risks becoming proof of retaliatory custom. If credential denial becomes the preferred method of enforcing outrage, liability flows upward with the same inevitability as responsibility.

Selective outrage may succeed politically. Under Monell, it fails legally.

IX. Chislett and the Judicial Rejection of Optics-Driven Discipline

The NYPD’s current “overtime abuse” posture cannot be understood as a neutral compliance initiative. It must be understood as governance by narrative—an institutional move in which political pressure and reputational crisis are translated into discipline, while the system that produced the outcome remains largely untouched. Recent decisions—including Chislett—are best read as part of a broader judicial trend: courts are becoming less tolerant of post-scandal enforcement that functions less like rule-based regulation and more like a retrospective moral campaign. In other words, courts are increasingly skeptical of reforms staged as punishment.

This matters because the Tisch administration’s public brand depends on a highly specific performance: a “savior” arrives, the institution becomes “disciplined,” and the prior era is recast as a moral failure rather than a management failure. That is political theater. But it is also litigation posture, because once the NYPD labels a system output “abuse,” it manufactures a justification for consequences that will predictably fall down the hierarchy rather than up. And once consequence becomes the purpose, the name changes. Selective outrage becomes retaliation.

The judicial concern reflected in Chislett and comparable cases is not abstract. It is about temporal honesty and institutional consistency—two things the NYPD’s overtime narrative is designed to avoid.

First, temporal honesty. Courts have long understood that an employer cannot credibly punish what it knowingly permitted, relied upon, or normalized, unless the employer can show clear rule boundaries, fair notice, and consistent enforcement. When agencies discover “abuse” only after a scandal becomes politically useful, judges ask the obvious question: what changed—conduct, or narrative? If the answer is narrative, then “reform” begins to resemble retaliation in a suit and tie.

Second, institutional consistency. Courts increasingly analyze whether discipline is being used to solve optics rather than enforce standards. Optics-driven discipline tends to share identifiable features: selective targeting, vague charges (“integrity,” “abuse,” “unbecoming”), and retrospective reframing of what was previously ordinary. It also tends to avoid meaningful structural change—understaffing, deployment mandates, and performance metrics remain intact, while individuals are made to absorb the consequences. The NYPD’s overtime “crisis” fits this pattern cleanly. Overtime at the NYPD did not appear spontaneously; it is the predictable output of chronic understaffing, politically imposed deployment mandates, command-level approvals, and performance metrics that assume omnipresence without funding it. The system was built. It was used. It was budgeted. Then it became scandal.

That is where courts are moving: away from deference to labels and toward scrutiny of function.

Chislett is useful here not because it is “about overtime,” but because it is emblematic of judicial resistance to institutional bait-and-switch: “We tolerated this, we benefited from this, and now we will punish you for it because the narrative demands a villain.” That is not compliance. That is scapegoating as management strategy. And courts are increasingly unwilling to treat it as neutral discipline, particularly where consequences are imposed through discretionary levers that can be deployed selectively and explained vaguely.

This is why credential-related retaliation—POST certification interference, denial of “good guy” letters, refusal to issue or renew identification cards—has become the preferred enforcement mechanism in agencies like the NYPD. These are “paper decisions” that function as sanctions while preserving plausible deniability. The institution says: “This is administrative.” The employee experiences: “This is punishment.” Courts, as Perros makes vivid, are increasingly willing to look past the label and evaluate the consequences: humiliation, reputational injury, employability impairment, and safety risk. The fact that these sanctions are inflicted without an overt suspension or formal termination does not make them less coercive; it makes them more attractive to institutions seeking to discipline without due process friction.

That is exactly why the NYPD’s current posture is dangerous. When the Tisch administration is marketed as a moral corrective and overtime is framed as proof of prior decadence, the institution will inevitably require visible enforcement to sustain the story. The question becomes: who pays for that enforcement? Historically and predictably, the NYPD’s answer has not been leadership accountability. It has been downward consequence—especially toward those already placed on conditional legitimacy inside the organization: Black officers, Latino officers, women, and others outside the Department’s traditional White-male power networks. When White male beneficiaries of overtime systems and internal accommodations dominated the narrative, the posture was often selective silence: quiet rule adjustments, recalibrated expectations, and managerial tolerance framed as “meeting the needs of the Department.” When the perceived beneficiaries shift—particularly toward disfavored groups—the same conduct is reframed as moral defect. That is not speculation; it is the operational logic of selective outrage.

Courts are increasingly attuned to that distributional reality. Anti-retaliation law is not only about explicit “because you complained” causation. It is also about predictable deterrence—whether an employer’s conduct would dissuade a reasonable employee from engaging in protected activity, separating from service, reporting violations, or challenging unlawful practice. Optics-driven discipline in a high-control public employer like the NYPD produces precisely that deterrence, especially when enforced through credential gatekeeping. The message becomes: “You may comply with today’s system, but tomorrow we will call it abuse—and we control the paperwork that determines whether you can work, carry, retire safely, or hold standing.” That is retaliation by architecture.

The other trend visible in judicial treatment of these cases is skepticism of “post-scandal reform” that is not prospective. Courts do not reward institutions for moralizing after the fact. They look for coherent rulemaking, documented standards, and fair enforcement. The more an institution relies on vague integrity rhetoric and discretionary paper sanctions, the more it invites the inference that discipline is being used as narrative management rather than lawful governance.

That inference is amplified where leadership branding is central to the enforcement posture. The Tisch administration’s “reformer” image is not incidental; it is the engine of the current narrative. If reform is being performed as theater—discipline for headlines, “accountability” aimed downward, and structural drivers left intact—courts will be more willing to treat the resulting sanctions as pretextual. “New era” rhetoric does not immunize an institution; it raises the stakes of its choices, because it invites comparison between what is said and what is done.

The through-line is simple: Chislett and similar decisions reflect a judiciary increasingly unwilling to let public employers substitute optics for standards. The NYPD can reform prospectively. It can staff honestly. It can revise deployment mandates. It can change overtime authorization architecture. What it cannot do—without legal exposure—is rewrite history by punishing employees for functioning inside a system the NYPD designed, approved, and relied upon. Once outrage is used to justify downward consequence, the line is crossed. Selective outrage acquires its second name. It becomes retaliation.

X. The Pattern Exposed: Selective Outrage as Institutional Self-Preservation

By the time an institution reaches for selective outrage, it is no longer attempting to govern. It is attempting to preserve itself. What is unfolding inside the New York City Police Department under the banner of “overtime abuse” is not a discrete scandal, nor an earnest effort at fiscal discipline. It is the latest iteration of a long-standing institutional survival strategy: when systemic design choices become politically inconvenient, the institution reframes them as individual moral failures and deploys discipline downward to protect leadership upward.

This pattern is not subtle. It is recursive.

The NYPD builds a system—chronic understaffing combined with expansive deployment mandates, layered approval structures, and performance metrics that reward omnipresence without funding it. That system produces predictable outcomes: reliance on overtime, normalization of extended tours, and institutional dependence on labor flexibility. Leadership approves it. Budget offices forecast it. Payroll processes it. The Department functions because of it.

Then the political climate shifts.

Media pressure intensifies. City Hall demands optics. A new administration—marketed as reformist, technocratic, and morally corrective—requires contrast to justify its authority. The same system that was once indispensable becomes rhetorically toxic. The outputs are relabeled. Overtime is no longer necessity; it is “abuse.” Compliance becomes excess. Participation becomes complicity.

At that moment, selective outrage is activated.

Selective outrage is not about uncovering wrongdoing. It is about reallocating blame. It collapses architecture into character. It transforms collective design into individual defect. Most importantly, it redraws the accountability map so that consequences travel downward and outward, never upward or inward.

At the NYPD, this redirection predictably tracks power, race, and gender. When White male officers embedded within legacy command networks or politically insulated units benefited disproportionately from institutional accommodations—including overtime flexibility, assignment latitude, and informal tolerance—the Department’s response was historically quiet recalibration. Rules were bent. Practices were justified as “operational need.” Silence functioned as endorsement.

When similar or identical outcomes are associated with Black officers, Latino officers, women, or others outside the Department’s traditional power core, the response changes tone. Silence becomes scrutiny. Accommodation becomes investigation. The same conduct is recast as ethical lapse. The same system output becomes evidence of moral failure. The asymmetry is not incidental; it is structural. Selective outrage is how hierarchy survives reform rhetoric.

This is why retaliation follows so naturally. Once an institution commits to selective outrage, it must demonstrate seriousness. Outrage without consequence is hollow. But consequence aimed upward threatens the very structure the institution is trying to preserve. So discipline is displaced onto safer targets—those with less institutional protection, less political insulation, and less narrative credibility.

In the modern NYPD, that displacement increasingly takes the form of credential and paper-based sanctions. Rather than overt termination or suspension—which invite procedural scrutiny—institutions rely on subtler levers: delays or revocations of POST certification, denial of “good guy” letters, refusal to issue or renew police identification cards, stalled approvals, unexplained holds. These actions are framed as administrative, but function as punishment. They impair employment prospects, damage reputation, expose individuals to safety risk, and signal internal disfavor.

Crucially, these mechanisms allow leadership to maintain plausible deniability. The institution can say, “No one was disciplined,” while the affected employee experiences real, material harm. Courts, as seen in Perros, are increasingly unwilling to accept that fiction. But institutions persist because the internal benefits are immediate: control without transparency, punishment without admission, retaliation without naming it.

The Tisch administration’s role in this pattern is not accidental. Its public image as a “savior” depends on visible contrast—an identifiable wrong that can be condemned, and identifiable actors who can be disciplined. Structural reform is slow, expensive, and politically risky. Narrative reform is immediate and inexpensive. Selective outrage supplies the storyline. Retaliation supplies the enforcement.

This is institutional self-preservation masquerading as integrity.

The danger of this strategy extends beyond individual harm. It corrodes institutional memory. Employees learn that compliance offers no protection. Supervisors learn that approvals granted in good faith may later be reclassified as negligence or misconduct. Officers of color and women—already navigating conditional legitimacy—learn that visibility itself can become liability. The rational response is silence, disengagement, and risk avoidance. Whistleblowing is chilled. Separation becomes hazardous. Lawful wage enforcement becomes dangerous.

At that point, the institution has succeeded in preserving itself—but only by sacrificing trust, legality, and professional integrity.

What makes this moment legally significant is that courts are no longer blind to the pattern. The line of cases you have identified—Becker, Center, Anderson, Mid-Hudson, Perros, and now Chislett—forms a coherent judicial rejection of institutional gaslighting. The law does not permit employers to design systems, benefit from them, and then disown those systems through moral reframing when politics demand a villain. Nor does it permit retaliation disguised as reform, particularly when enforced through discretionary credential controls.

Selective outrage is thus not merely a cultural phenomenon. It is evidence. It reveals motive. It explains why retaliation follows scandal so reliably. And in the NYPD, under the Tisch administration’s reform theater, it exposes a familiar truth: when institutions feel threatened, they do not change. They protect themselves.

XI. Conclusion: Reform Without Amnesia

The law does not require public institutions to be perfect. It requires them to be honest. What it does not tolerate—no matter how carefully choreographed—is reform without memory.

The New York City Police Department stands at precisely that crossroads. Under the Tisch administration, the Department has embraced the language of modernization, discipline, and accountability. It has promised a break from the past. But a break that depends on selective outrage is not reform; it is erasure. And erasure is incompatible with legality.

Overtime did not suddenly become abusive because a new commissioner arrived. It became rhetorically useful. The system that produced it—chronic understaffing, politically imposed deployment mandates, command-level approvals, and performance metrics untethered from capacity—remains intact. What has changed is the story being told about that system, and the distribution of consequences flowing from it.

That distribution matters.

When accountability is displaced downward—onto individual officers, supervisors, retirees, and employees whose only “misconduct” was functioning within approved structures—the institution sends a clear message: history will be rewritten, and compliance will not be remembered. For Black officers, Latino officers, women, and others outside the NYPD’s traditional White-male power core, that message is amplified by experience. They have seen this pattern before. They know that outrage is not applied evenly, and that reform rhetoric often masks retrenchment rather than transformation.

The cases discussed throughout this piece do not merely support that intuition; they codify it. Becker rejects the laundering of systemic failure through individual blame. Center narrows the “rogue employee” narrative to near extinction. Anderson and Mid-Hudson foreclose employer attempts to profit from their own control and recordkeeping failures. Perros exposes credential retaliation for what it is: punishment with real-world consequences, even when delivered through paper. Chislett signals growing judicial impatience with post-scandal discipline untethered from contemporaneous rules.

Taken together, these cases say something institutions prefer not to hear: reform must be prospective, structural, and evenly applied. It cannot be retroactive moralization. It cannot be selective. And it cannot function as retaliation without consequence.

The NYPD has choices. It can confront the real drivers of overtime—staffing levels, deployment mandates, budget honesty, and command accountability. It can design systems that align capacity with expectation. It can enforce rules going forward with clarity and fairness. Or it can continue down the path of narrative management, punishing yesterday’s compliance to satisfy today’s optics.

The first path is difficult. It requires political courage, institutional humility, and a willingness to disrupt internal hierarchies. The second is familiar. It preserves leadership, insulates architecture, and sacrifices individuals. History suggests which path institutions prefer.

But the law is increasingly clear about the cost of that preference.

Selective outrage may succeed as theater. Retaliation may succeed as control. Neither succeeds as reform. Courts are not obligated to participate in institutional amnesia, and neither are employees required to absorb the consequences of systems they did not design.

Reform without memory is not reform. It is reenactment.

And in the NYPD—an institution with centuries of experience perfecting the appearance of change while preserving power—the choice now is stark. Either reform will be grounded in truth, structure, and accountability that flows upward as well as down, or it will continue to rely on selective outrage and retaliatory consequence to manage perception.

The difference is not academic. It is legal. It is human. And it is already being litigated.

Selective outrage has a second name. The courts know it. The employees feel it. The only remaining question is whether the NYPD, under the Tisch administration, will confront it—or continue to perform reform until performance itself becomes evidence.

Reader Supplement

To support this analysis, I have added two companion resources below.

First, a Slide Deck that distills the core legal framework, case law, and institutional patterns discussed in this piece. It is designed for readers who prefer a structured, visual walkthrough of the argument and for those who wish to reference or share the material in presentations or discussion.

Second, a Deep-Dive Podcast that expands on the analysis in conversational form. The podcast explores the historical context, legal doctrine, and real-world consequences in greater depth, including areas that benefit from narrative explanation rather than footnotes.

These materials are intended to supplement—not replace—the written analysis. Each offers a different way to engage with the same underlying record, depending on how you prefer to read, listen, or review complex legal issues.