Why logs, metadata, and access histories are the new ‘Brady problem’ (metaphor)

Executive Summary

Body-worn cameras were marketed as transparency. But in modern excessive-force litigation, the decisive question is increasingly not what the footage shows—it is whether the City can prove the integrity of the evidence pipeline that produced the footage. When video is missing, incomplete, starts late, or ends early, the courtroom becomes a credibility contest. The only reliable antidote is verifiable proof of what happened to the evidence inside the system: logs, metadata, trackers, and access histories.

The New York City Comptroller’s audit of NYPD’s body-worn camera program describes a record ecosystem where oversight and completeness are not consistently assured. The Comptroller found activation rates are “lower than they should be,” and that footage was “missing and incomplete,” with NYPD not consistently conducting required reviews or collecting required documentation. The audit also reports that footage was not on file for 36% of incidents in the dataset and that where footage was on file, late activation or early deactivation occurred 18% of the time. In that environment, “the video” cannot be treated as self-authenticating transparency; integrity must be proven.

Crucially, the audit shows that NYPD already manages body-camera disclosure through structured tracking systems. The Comptroller reports that NYPD’s Legal Bureau BWC Unit tracks FOIL requests in an Intranet Tracker database (including incident information, requester contact information, and progress notes) and maintains separate spreadsheets tracking requests that were released and denied. The audit also describes formalized tracking of FOIL appeals through a Log of Appeals. Those internal systems illustrate the central claim of this thought-piece: the audit trail is not administrative residue; it is the evidentiary backbone that determines whether cameras function as transparency or as narrative control.

This piece reframes the accountability demand from “produce the video” to “prove the record.” It explains why audit trails matter, how missing integrity artifacts reshape litigation outcomes, and what an integrity-first disclosure model looks like—so that legitimacy is not presumed, but demonstrated.

I. The Audit Trail Is the Evidence

Why logs, metadata, and access histories are the new “Brady problem” (metaphor)

The public still thinks the fight over body-worn cameras is a fight over a video file. Did it exist? Was it produced? What does it show? That framing made sense when cameras were new and the novelty was visibility itself. But as policing scaled into mass recording, the decisive conflict moved again—away from the existence of footage and into the evidence pipeline that determines what footage becomes “the record.”

In modern excessive-force litigation, the most important evidence is increasingly not the image on the screen. It is the audit trail behind the image: the logs and tracking systems that show what was requested, what was located, what was categorized, what was reviewed, what was exported, what was denied, what was withheld, and who touched the record at each step. In a system where recordings can start late, end early, or never appear at all, credibility cannot rest on assurances. Credibility rests on whether the institution can prove—through contemporaneous records—how the evidence moved through its own hands.

That point sounds technical until you put it in human terms. A missing minute does not behave like a neutral absence. In court, a missing minute becomes a credibility vacuum. Juries do what human beings always do when they face a gap: they fill it. The party that carries institutional authority—uniform, structure, official confidence—often benefits when the record is incomplete, because the gap forces the factfinder to lean on narrative and demeanor rather than proof.

This is why the audit trail matters. It is the difference between “trust us” and “here is the chain.”

The Comptroller’s audit makes the audit-trail point unavoidable because it documents that NYPD already treats body-camera evidence as something that must be tracked, managed, and escalated through internal systems. The audit describes how the Legal Bureau’s body-camera unit tracks requests for body-camera footage in an internal Tracker database that includes incident details, requester contact information, and progress notes. It also describes separate tracking for requests that were released and denied. That’s not a public-relations detail. It’s the architecture of control. It confirms that “the footage” is not a thing that simply exists; it is an object that passes through a workflow governed by classification decisions and administrative handling.

The audit then describes formalized tracking of appeals through a dedicated appeals log, and it reports what should be a flashing warning light for anyone who thinks disclosure decisions are stable: between 2020 and 2024, NYPD received 355 appeals of body-camera FOIL decisions and granted 344 of them—97%. When a system reverses itself at that rate, it tells you something structural: the first disclosure decision is frequently not the last one, and escalation is often the practical mechanism that unlocks the record.

That is not merely a FOIL story. It is a record-integrity story. It tells you that “what the record is” can change depending on how hard the requester pushes, how long the requester waits, and whether the requester forces additional review. When transparency depends on escalation, transparency becomes conditional. And conditional transparency is the opposite of the public promise that made cameras politically palatable in the first place.

Now bring that logic into litigation, where the stakes are constitutional and the consequences are existential. The plaintiff is not asking for footage as a media artifact. The plaintiff is asking for an evidentiary record that can be tested. And testing is impossible if the system cannot produce the integrity artifacts that explain what happened inside the pipeline: how the footage was handled, who accessed it, whether it was reviewed, how it was categorized, whether it was exported, and whether any steps occurred that would reasonably affect completeness or continuity.

This is where the Comptroller’s findings about the underlying camera system become critical. The audit reports that footage was not on file for 36% of incidents in the dataset it reviewed. It also reports that even when footage was on file, cameras were activated late or deactivated early 18% of the time. Those two numbers tell you everything you need to know about why “just give me the video” is no longer a serious accountability demand. If a substantial share of incidents have no footage on file, and nearly one in five available recordings begins late or ends early, the legal system cannot treat video as self-authenticating truth. The system must ask the pipeline questions, because the pipeline is where completeness is won or lost.

The Comptroller also reports that oversight mechanisms are inconsistent: self-inspections for activation were missing for 53% of sampled months, and the Department did not consistently aggregate results to identify anomalies or trends. That matters because integrity is not a one-time event. It is a discipline. A system can survive individual failures if it reliably detects, aggregates, and corrects them. But when the detection and trend mechanisms are missing or sporadic, failure becomes normalized. The institution loses the ability to say, with credibility, “we police our own compliance.” It also loses the ability to prove that noncompliance is isolated rather than patterned.

The department’s own stated position in the audit also reveals how accountability can be quietly limited by “administrative” framing. NYPD told auditors that trend analysis of late activation and early deactivation is not accomplished through data pulls and that evaluating proper activation requires watching entire videos for context, making it difficult to scale across the volume of annual recordings. The Comptroller disagreed and described that position as dubious, noting that auditors were able to aggregate review results and perform trend analysis. That dispute is not about analytics. It is about whether the institution will treat integrity as a scalable obligation or as an ad hoc aspiration.

This is why the Monitor’s diagnosis belongs in Section I even before we get to the more detailed oversight sections. The Monitor describes an ongoing lack of meaningful accountability and states that relying solely on training without discipline has proven ineffective. That is the cultural layer that makes the audit trail decisive. In an environment where consequences are inconsistent, “failures” do not self-correct. They repeat. And when failures repeat in a record system, the record itself becomes a contested battlefield.

So here is the central thesis of this piece: the audit trail is not administrative residue; it is the evidence layer that determines whether body-worn cameras function as transparency or as narrative control. The existence of internal tracking systems is not incidental. It is the Department acknowledging, in practice, that the record is a workflow. Once you accept that, the next move follows automatically: accountability demands must evolve. They must shift from “produce the video” to “prove the record.”

If you want transparency that doesn’t depend on faith, you don’t start by pressing play. You start by demanding the pipeline.

II. The Record Already Has a Paper Trail—So Why Is the Truth Still So Negotiable?

If the public wants to understand why body-worn camera disputes persist, it should start with a counterintuitive fact: the record system is not chaotic. It is organized. It is tracked. It is managed.

That is precisely the problem.

The Comptroller’s audit describes an internal structure for handling body-camera disclosure that looks nothing like the casual public assumption that “someone just pulls the video.” The audit describes how the Legal Bureau’s body-camera unit tracks body-camera FOIL requests in an internal Tracker database that includes incident information, requester contact information, and progress notes. It also describes separate spreadsheets tracking which requests were released and which were denied, and an appeals log tracking FOIL appeals. This is not window dressing. It is a process map—an evidence pipeline with checkpoints, classifications, and decisions.

Once you absorb that, you see why “video” is no longer the right accountability unit. The right unit is the pipeline, because the pipeline is where discretion lives. Progress notes are not neutral; they are narrative. Categorization is not neutral; it can determine how a request is handled, how long a file is retained, how quickly it moves, and which parts are treated as responsive. Release and denial tracking is not neutral; it reflects judgment calls about what the public gets to see and when. The appeals log is not neutral; it is the record of institutional reconsideration—proof that the first answer is often not the final answer.

That last point is critical. The Comptroller reports that between 2020 and 2024, NYPD received 355 appeals and granted 344 of them—97%. In human terms, that means escalation is not an exception. It is a common route to disclosure. And when a system produces a 97% reversal rate on appeal, the public is entitled to ask why the initial posture so often fails to match the final result. In a transparency regime, a reversal rate that high doesn’t read like careful gatekeeping; it reads like a process that requires pressure to produce what should have been produced in the first instance.

This is where the “audit trail” becomes evidentiary, not administrative. If the system is tracked, then the tracking records are the proof of what happened inside the institution. They show when a request was received, what incident it was linked to, what actions were taken, what reasons were recorded for delay or denial, and what changed on appeal. That audit trail is the only practical way to evaluate whether the system behaves like a transparency mechanism or like a negotiation mechanism. And a system that behaves like a negotiation mechanism produces a predictable outcome: the truth becomes conditional on persistence.

Now bring that dynamic into excessive-force litigation, where the stakes are higher and the incentives are sharper. In court, “the truth” is what can be proven. Proof depends on integrity. Integrity depends on contemporaneous records that show how the evidence was handled. The Comptroller’s audit, in effect, confirms that the institutional machine already generates those records—it relies on trackers, progress notes, spreadsheets, and logs to manage the movement of footage through its own process. The legal community’s mistake has been treating those artifacts as housekeeping rather than as the spine of evidentiary reliability.

The Comptroller’s findings about the underlying completeness of footage are what make this urgent rather than academic. The audit reports that footage was not on file for 36% of incidents in the dataset and that when footage was on file, late activation or early deactivation occurred 18% of the time. Those numbers are not simply quality-control statistics. They are the reason an integrity-first approach is mandatory. If footage is frequently missing, and if existing footage is frequently discontinuous, then the legal system cannot treat the footage as the whole record. It must treat the audit trail as the record’s backbone—because the audit trail is what can confirm whether the missingness is explainable, whether it is patterned, and whether the institution’s own integrity mechanisms detected it and responded.

The audit then explains why the system’s ability to self-correct is uncertain: self-inspections for activation were missing for 53% of sampled months, and the Department did not consistently aggregate review results to identify anomalies or trends. When the self-inspection record is missing more than half the time, “we monitor compliance” stops being a verifiable assertion and becomes an untestable reassurance. When results are not aggregated and trends are not systematically identified, the institution loses the ability to say with credibility that repeat failures are being detected and corrected. And once repeat failures are not reliably detected, the system begins to produce what the public experiences as “camera issues” and what litigators experience as “record integrity disputes.”

This is also where institutional incentives quietly reshape reality. A system that cannot scale its integrity analytics will always describe failures as isolated. It will always attribute late activation to a lapse, early deactivation to a mistake, and missing footage to misfortune. Without scalable oversight and auditable trend outputs, those explanations cannot be tested. And the untestable explanation becomes the default narrative. That is how legitimacy erodes—not always through a scandal, but through a slow normalization of unprovable claims.

The Monitor’s report supplies the governance context that explains why this matters beyond any single request or lawsuit. The Monitor describes an ongoing lack of meaningful accountability and states that relying solely on training without discipline has proven ineffective. That is a system-level warning: when consequences are inconsistent, deficiencies persist. Apply that to the evidence pipeline and the implication is direct: if integrity failures do not trigger predictable escalation and meaningful consequences, the pipeline will keep producing missingness and discontinuity. The record remains negotiable.

So Section II sharpens the argument introduced in Section I. The audit trail is not evidence only because it exists. It becomes evidence because it is the only objective way to test institutional claims in a system where the footage itself is often incomplete. In a world where body-worn cameras were supposed to settle facts, the audit trail is what now determines whether facts can be settled at all.

This is why the phrase “prove the record” is not rhetorical. It is the minimal accountability demand that matches the structure NYPD already uses internally. The Department already tracks the pipeline. The legal system must require the Department to produce the pipeline when the record is contested—because without the pipeline, the court is left with the most dangerous currency in police cases: credibility unmoored from verification.

If Section I tells the reader that the audit trail is the evidence, Section II tells the reader why: because the institution already treats the record as a tracked process, and the record itself—by the City’s own audit—cannot be presumed complete.

III. Discretion Is the Enemy of the Record: Why Policy Design Determines Whether the Audit Trail Can Tell the Truth

Once you accept that the audit trail is evidence, the next question becomes unavoidable: what is the audit trail actually measuring? In a body-worn camera system, the audit trail is not measuring philosophy. It is measuring compliance with a set of decisions that happen before anyone ever argues about “the video.” Those decisions are mostly not cinematic. They are administrative. But they are decisive: when to activate, when to keep recording, how to categorize, whether to flag, whether to review, whether to escalate, whether to treat a gap as an anomaly or as “normal.”

This is where the public story breaks down. The public believes cameras create objectivity. The evidence says cameras create objectivity only when policy design and supervision shrink discretion in the places where discretion naturally expands. Otherwise, the record becomes optional at the margins—and it is at the margins where force cases live.

National research makes the point in a way that is impossible to dismiss as “lawyer cynicism.” The finding is not simply that cameras have “mixed results.” The finding is that results depend on whether activation rules are strict and comprehensive or discretionary and porous. In departments with stricter activation requirements, measurable accountability outcomes appear; in departments with more discretionary activation policies, those measurable outcomes do not appear in the same way. The takeaway is straightforward: a camera that can be switched on and off at will is not a transparency tool. It is a tool that records what the institution is prepared to have recorded.

That same research highlights how uneven activation requirements can be across real-world contexts. In some scenarios—especially one-on-one encounters—activation is widely required across agencies. In other scenarios, especially those involving public events, activation mandates are far less consistent. The policy choice is telling. When a context is volatile, crowded, politically sensitive, and likely to produce contested narratives, discretion tends to increase. If policy design gives discretion space in those contexts, the camera becomes least reliable at precisely the moment it is most socially necessary.

This is not merely a critique of individual officers. It is a critique of system design. Discretion is not a moral defect. It is an organizational reality. Officers work in dynamic conditions. Supervisors triage. Commands manage risk. But if discretion is left unbounded, it migrates to the points of maximum pressure. In a police encounter, maximum pressure is exactly where force becomes likely and where later litigation becomes predictable. If discretion governs the existence of the record at those points, then the camera becomes a credibility amplifier for whoever controls the narrative after the fact.

Now bring that back to what the Comptroller found in New York City. The audit reports that footage was not on file for a substantial share of incidents in the dataset and that, even when footage was on file, late activation or early deactivation occurred at a meaningful rate. Those two findings are not just compliance failures; they are the operational signature of discretion living in the wrong place. A system cannot promise “transparency” if the record often does not exist or often begins after the critical moment has already passed. The best evidence in a force case is often the beginning—approach, commands, escalation, resistance, and the moment force starts. If the video begins after that, the factfinder is forced to reconstruct the most important part of the encounter with inference and credibility.

This is also where the audit trail becomes more than a back-end log. It becomes the only tool capable of distinguishing between a truly exceptional failure and a patterned design problem. In a healthy system, the audit trail would show activation compliance, continuity, and the reasons for any interruption. It would show whether a gap triggered internal review, whether the gap was categorized as improper activation, and whether repeated failures by the same member or the same unit triggered escalating consequences. In other words, the audit trail is how the institution proves it treats discretion as a risk that is managed rather than as a reality that is tolerated.

But the Comptroller’s audit identifies oversight weaknesses that undermine that proof function. Self-inspections for activation were missing for more than half of sampled months. Aggregation to identify anomalies and trends was not consistently performed. And the audit explains why that matters: without trend analysis and systematic aggregation, the institution has limited assurance that repeat activation failures are even being detected, much less corrected. That is the structural condition that allows discretion to persist in practice even when policies exist in theory.

This is why policy design cannot be divorced from audit trail design. If an institution says activation must occur, but does not enforce a process that reliably documents compliance, aggregates failures, identifies repeat patterns, and imposes predictable consequences, then the policy becomes aspirational and the audit trail becomes thin. A thin audit trail produces the worst of both worlds: it allows integrity problems to recur while depriving courts of the records needed to test institutional explanations. It turns the legal inquiry back into what cameras were supposed to reduce: a credibility contest.

The Monitor’s reporting adds the cultural layer that explains why thin audit trails persist. The Monitor describes ongoing lack of meaningful accountability and emphasizes that relying on training without discipline has proven ineffective. That warning matters here because camera integrity lives or dies on consequences. If improper activation is treated as a coaching opportunity rather than as a serious integrity defect, repeat failure becomes inevitable. And if repeat failure becomes inevitable, missing footage becomes routine. Routine missingness creates routine credibility vacuums. Routine credibility vacuums corrode legitimacy.

The deeper point of Section III is this: the audit trail can only function as evidence if the institution designs policy to reduce discretion where it matters and designs oversight to make compliance provable. Otherwise, the audit trail becomes merely an administrative memory of how the institution managed access, rather than an integrity instrument capable of proving that the record is complete, continuous, and trustworthy.

This is why “audit trail” is not a technical obsession. It is the natural endpoint of accountability in the era of mass recording. When policy design leaves the existence of the record in the hands of discretion, the only way to restore trust is to demand the artifacts that can verify—or falsify—the institution’s story about what happened to the evidence. And when those artifacts are missing, the absence itself becomes a fact: the system cannot prove the record.

Section III therefore sets up the practical shift this thought-piece will insist on going forward: the public should stop treating camera debates as gadget debates, and the legal community should stop treating camera disputes as clip disputes. The real question is whether the institution has built a record system where discretion is constrained and integrity is provable. If the answer is no, then cameras will keep producing the same outcome: not clarity, but argument—and not trust, but negotiation.

IV. Workflow, Not Window: How “The Video” Becomes the Record—And How the Record Becomes a Narrative

Most people think a body-worn camera creates a straightforward artifact: a recording. Something you can watch, interpret, and use to settle a dispute. That assumption treats video like a window—look through it and you see what happened.

But in litigation, video is not a window. It is a product. And like any product, it is shaped by the process that manufactures it.

That process is the evidence pipeline.

The simplest way to understand the pipeline is to ask a plain question: how does a recording become “the record”? It does not become the record at the moment the encounter happens. It becomes the record after a chain of events occurs inside an institution—events that can add friction, create gaps, and shape narrative without anyone ever “editing” in the way the public imagines.

The Comptroller’s audit, read carefully, is a guide to this reality. It does not describe a casual or ad hoc approach to body-camera records. It describes a structured disclosure operation. The Legal Bureau’s body-camera unit tracks requests in an internal Tracker database that includes incident information, requester contact information, and progress notes; it maintains separate tracking for releases and denials; and it tracks appeals through an appeals log. Once you see that architecture, it becomes difficult to keep pretending that “the video” is merely something that exists waiting to be retrieved. The institution is managing a workflow, and every workflow has decision points.

Decision points are where narratives are shaped.

A progress note is a decision point because it records what someone believes the request is about and what steps they believe are required. A release/denial spreadsheet is a decision point because it reflects an institutional conclusion about whether disclosure is appropriate at that stage. An appeals log is a decision point because it reflects when a conclusion was revisited—often after the requester applied pressure. And a system that records those decisions creates a second, parallel record: not the camera record of the street encounter, but the administrative record of how the institution chose to handle the camera record.

That administrative record—what we are calling the audit trail—often becomes more revealing than the footage itself, particularly when footage is missing, incomplete, or discontinuous.

This is where the Comptroller’s quantified findings are not just “bad statistics.” They are the reason the pipeline must be treated as evidence. The audit reports that footage was not on file for 36% of incidents in its dataset, and that where footage was on file, late activation or early deactivation occurred 18% of the time. Those facts mean the “window” assumption is unsafe. The record is frequently not whole. And when the record is not whole, the institution’s administrative handling becomes the only available proof of what happened to the evidence.

The pipeline, in plain language, is the story of five questions.

First: did the recording exist in the first place? That question is not philosophical; it is operational. It depends on activation and continuity. The audit’s late-activation/early-deactivation finding shows why this is not a rare edge case. If recording begins late or ends early at meaningful rates, the system is producing partial narratives by default.

Second: if the recording existed, was it preserved as a complete artifact? In a mature accountability system, this would be where oversight mechanisms detect noncompliance and correct it. But the Comptroller reports missing self-inspections for activation across more than half of sampled months, as well as inconsistent aggregation to identify anomalies and trends. That means the pipeline’s self-correction mechanisms are not consistently provable, and the institution’s ability to say “we police compliance” becomes a claim that often cannot be verified with documentation.

Third: how was the recording categorized? Categorization is the hidden lever most members of the public never see. It can govern retention, review priority, and the pathway the file takes through internal systems. If categorization decisions are treated as administrative rather than as integrity-critical, they become a quiet way for a system to reduce visibility. That is why the Monitor’s warning about administrative focus matters here. When oversight concentrates on activation and categorization as checkboxes rather than on constitutional outcomes, the pipeline can produce the appearance of compliance while still failing to produce reliable accountability.

Fourth: who reviewed the footage, and what did the institution do with what it saw? The Monitor’s account of ComplianceStat shows video review being used as a governance tool. But the Monitor also describes the limits of review when consequences are inconsistent: initial responses to identified deficiencies were insufficient, retraining was used where discipline was needed, and sustained change depended on leadership demanding accountability over time. That is a lesson about pipelines. A pipeline is not just storage; it is consequence. If review does not reliably lead to correction, the pipeline can identify problems without reducing them.

Fifth: what was produced externally, and under what conditions? This is where FOIL becomes a supporting mirror. The Comptroller reports that NYPD took an average of 133 business days to grant or deny FOIL requests for body-camera footage, with the longest taking more than four years, and that appeals resulted in production 97% of the time. That is a system in which disclosure often arrives after escalation. In other words, production itself is part of the narrative environment. If the record appears only after procedural pressure, it changes how the public experiences accountability—and it changes how litigators experience discovery. It teaches the same lesson: access is not automatic; it is negotiated.

This is why “workflow not window” is the correct frame for any serious discussion of body-worn cameras in 2026. The camera is only the first step. The meaning of the footage—its completeness, its continuity, its credibility—depends on what happens after it is recorded. And what happens after it is recorded is precisely what the audit trail documents.

A court that sees only the footage is being asked to evaluate the incident with one eye closed. The open eye sees what is shown. The closed eye cannot see what is missing, why it is missing, who handled the file, whether oversight was triggered, and whether the system treated the missingness as an anomaly or as normal. The audit trail is the evidence that opens the second eye.

If the public wants transparency and the legal system wants proof, the pipeline must be treated as a substantive object of accountability. The question cannot be “do you have body cams?” The question has to be “can you prove, with auditable records, what happened to the evidence from the moment it was created to the moment it was produced?”

That is the point where a camera program stops being a technological ornament and becomes what it claimed to be: governance infrastructure.

And it is the point where discovery stops being a procedural fight and becomes what it actually is: the test of whether the state can be trusted with the record of its own power.

V. The Integrity Artifact Model: What “Prove the Record” Actually Requires

A serious accountability system does not ask the public, the courts, or injured plaintiffs to take it on faith. It produces integrity artifacts—reliable, repeatable outputs that prove the record is what the institution says it is. In the body-worn camera context, integrity artifacts are the documentary backbone that turns a clip into evidence.

This section puts a name to what courts and litigators are increasingly doing implicitly: moving from a footage-first mindset to an integrity-first mindset. The slogan version is “prove the record.” The operational version is more concrete: prove completeness, prove continuity, prove handling, prove review, prove escalation, and prove consequences.

The need for this model is not theoretical. The Comptroller’s audit reports that footage was not on file for 36% of incidents in the dataset and that where footage was on file, late activation or early deactivation occurred 18% of the time. Those findings alone mean the record cannot be presumed complete. When completeness is not presumed, the integrity artifacts become the only way to determine whether the system failed, whether the failure was detected, and whether the institution’s explanation is testable.

An integrity artifact model has five core categories. Each category is legible to the public, and each category is indispensable to the legal community.

The first category is the existence proof: the artifacts that show what should exist and whether it exists. In a force case, “what should exist” is rarely a mystery. There is a dispatch, a response, a unit assignment, an incident report, an arrest packet, or some internal reference to the encounter. The integrity question is whether the recording exists for that event and whether the absence is explainable in a way that can be verified, not simply asserted. If footage is not on file for a substantial share of incidents in an audited dataset, then the institution must be able to prove, with system records, why the file does not exist in a particular case and whether the absence triggered any internal review. Otherwise, the absence becomes an untestable narrative, and untestable narratives are exactly how credibility contests replace proof.

The second category is the continuity proof: the artifacts that show whether recording began when it should have begun and ended when it should have ended. Late activation and early deactivation are not neutral issues. They remove context. They remove the lead-up that makes later conduct legible. They remove the resolution that often determines whether force was necessary, whether medical aid was provided, and whether post-incident statements were consistent or opportunistic. If late activation and early deactivation occur at meaningful rates in an audited sample, continuity cannot be treated as an assumption. It must be proven with integrity artifacts that establish the start time, end time, and whether any gaps were treated as compliance failures.

The third category is the handling proof: the artifacts that show how the record moved through the institution’s own system. This is where the audit trail becomes the evidence. The Comptroller’s audit describes a disclosure workflow that uses an internal Tracker database with incident information, requester contact information, and progress notes, as well as separate tracking for releases and denials and an appeals log. Those are integrity artifacts. They show the internal life of the record: when the request came in, what it was linked to, what decisions were made, and whether those decisions changed under pressure. A record system that can track these details internally cannot credibly argue that it is unreasonable to demand similar integrity artifacts in litigation when the record’s completeness is contested. The institution has already built the machinery. The question is whether the machinery can be produced for adversarial testing.

The fourth category is the oversight proof: the artifacts that show whether compliance checks were performed and whether patterns were identified. This is where the Comptroller’s findings about missing self-inspections and limited aggregation become decisive. If self-inspections for activation are missing for more than half of sampled months, and if results are not consistently aggregated to identify anomalies and trends, then the institution cannot reliably prove that its integrity system is functioning as designed. In that environment, the legal community should expect two recurring phenomena: first, repeat failures framed as isolated; second, “we reviewed this” assertions that cannot be verified with documentation. Oversight proof is how a system demonstrates it is not merely recording, but governing the recording.

The fifth category is the consequence proof: the artifacts that show what happened when failures were detected. The Monitor’s reporting supplies the cultural reason this category matters. The Monitor describes an ongoing lack of meaningful accountability and emphasizes that relying solely on training without discipline has been ineffective. That point is not abstract. It is a design principle. A system that treats integrity failures as coaching moments without predictable escalation creates an incentive environment where failures persist. Consequence proof is what converts oversight from performance into governance. It documents whether repeat failures triggered meaningful responses, whether leadership demanded correction, and whether the institution treats record integrity as a constitutional obligation rather than an administrative preference.

Once you have these five categories, “prove the record” stops being rhetorical. It becomes a method. And the method clarifies what discovery must seek in a force case: not only footage, but the integrity artifacts that make footage testable. Without that method, courts are forced into the most dangerous posture in police cases: deciding contested facts without a complete record and then filling the gaps with credibility judgments.

The Integrity Artifact Model: A Framework for Verifiable Accountability

| Category | Operational Question | Primary Integrity Artifacts | Verified Anchor (Audit/Monitor Data) |

| 1. Existence Proof | Does the institution have a record for this specific event? | ICAD Dispatch Logs, Unit Assignment Sheets, BWC Inventory Lists. | 36% of incidents in the audited dataset had no footage on file. |

| 2. Continuity Proof | Did the recording capture the full “Pre-Force Window”? | Start/End Metadata, Activation Logs, ICAD Audit Results. | 18% of footage was activated late or deactivated early. |

| 3. Handling Proof | How did the record move through the administrative pipeline? | Intranet Tracker Database, Progress Notes, Release/Denial Spreadsheets. | NYPD Legal Bureau already maintains these internal tracking systems. |

| 4. Oversight Proof | Was compliance actually monitored by supervisors? | Contemporaneous Self-Inspection Logs, Trend Analysis Reports. | 53% of self-inspections were missing; Trend Analysis found to be “dubious.” |

| 5. Consequence Proof | Did non-compliance trigger a structured escalation? | Disciplinary Records, Command Removals, Corrective Action Logs. | Monitor: Training without discipline is ineffective; change requires “sustained effort.” |

This model also explains why FOIL belongs in the story as a public mirror. The Comptroller reports that NYPD took an average of 133 business days to grant or deny FOIL requests, with the longest taking more than four years, and that appeals resulted in production 97% of the time. That is the signature of a system where disclosure is frequently the product of escalation. Escalation-based disclosure trains the public to understand transparency as conditional. In litigation, escalation-based disclosure trains the parties to treat discovery as negotiation. The integrity artifact model is a direct response to that culture. It says: no. The record is not a negotiation. It is a thing that must be proven.

There is a final human point worth stating plainly. The integrity artifact model is not anti-police. It is anti-ambiguity. It protects officers from false accusations by proving what happened. It protects civilians from false narratives by proving what happened. It protects courts from making decisions in evidentiary fog. And it protects the institution’s legitimacy by replacing faith with verification.

That is what accountability looks like in the era of mass recording: not simply cameras, but governance of cameras. Not simply footage, but integrity artifacts. Not simply “we have a body-cam program,” but “we can prove the record.”

If Section IV explained how the pipeline manufactures the record, Section V defines what the system must produce to be credible. The next step is practical: translating these integrity categories into a disciplined set of demands—what the public should ask for, what lawyers should request, and what courts should normalize—so that audit trails become standard evidence rather than exceptional suspicion.

VI. The Integrity-First Disclosure Protocol: What to Demand, What to Test, and How to Stop Letting “Explanation” Substitute for Proof

If Sections I through V built the argument that the audit trail is evidence, Section VI answers the practical question: what does an integrity-first protocol actually look like in a force case or any contested police encounter where body-camera footage is central?

The goal is not to “over-lawyer” a production. The goal is to prevent the system from converting a missing or partial record into a credibility contest that predictably favors the institution. When footage is missing, starts late, ends early, or appears incomplete, the truth cannot be resolved by tone. It can only be resolved by integrity artifacts—records that allow the parties and the court to test what happened inside the pipeline.

An integrity-first protocol begins with a shift in mindset: stop treating “video” as the object of discovery and start treating “the record system” as the object. The video is one output. The record system produces multiple outputs—footage, categorizations, review traces, tracking notes, appeals records, and other internal handling artifacts. If the system already relies on internal trackers and logs to manage disclosure and review, then producing those artifacts in litigation is not an exotic request. It is the natural extension of how the institution already governs its own evidence.

The first step is a completeness map. This is not a technical exercise; it is a logic exercise. The institution should identify what recordings should exist for the event window and why. That includes every officer or unit reasonably expected to have been present, every camera assignment relevant to the response, and every time window that makes the event intelligible. Completeness is not just “the moment of force.” Completeness includes the approach, the escalation, the actual force, and the aftermath. If footage is missing for a meaningful share of incidents in an audited dataset, then a completeness map is not optional. It is the minimum predicate for determining whether the record is absent for a legitimate reason or absent in a way that should trigger a remedial response.

The second step is a continuity test. A late start or early stop is not a minor defect; it removes the narrative context that courts and juries need to assess reasonableness, threat, resistance, and necessity. A continuity test asks whether the recording runs through the encounter without gaps and whether any gaps are documented as compliance issues. It also forces a key distinction that is often blurred: “we have footage” is not the same as “we have the encounter.” A continuity test treats discontinuity as an integrity event that must be explained with documentation, not just asserted in a sentence.

The third step is the handling record. This is where the “audit trail is evidence” model becomes operational. The handling record is the administrative life of the footage inside the institution: when it was identified, how it was categorized, what internal notes exist about its status, and what decisions were made about release or withholding. If the institution maintains internal trackers with progress notes and separate release/denial tracking for disclosure requests, then the handling record is not speculative. It exists because the system relies on it. In an integrity-first protocol, those artifacts are treated like chain-of-custody documentation. They tell the court whether the record moved predictably or whether it was delayed, recharacterized, revisited, or produced only after escalation.

The fourth step is the review chain. A mature accountability system does not simply store footage; it triggers review where the stakes demand review. If an audited system has gaps in self-inspections, inconsistent aggregation, or limited trend visibility, that is precisely why the review chain matters in litigation: it is the only way to know whether the institution treated the incident as a record-integrity event or as an administrative inconvenience. A review chain asks who reviewed the footage, when, for what purpose, and whether any compliance deficiencies were identified. It also asks whether missingness or discontinuity triggered any internal scrutiny. If the institution cannot produce the review chain, that inability itself becomes probative of whether the integrity system is performing the role the public has been promised it performs.

The fifth step is pattern visibility. Integrity disputes often fail in court because each failure is framed as isolated. A battery died. A malfunction occurred. An officer forgot. An upload failed. Those explanations may be true in individual instances, but without trend visibility they are untestable. An integrity-first protocol therefore requires the institution to disclose whether the officer, unit, or command has a history of activation deficiencies, and whether the system aggregates results to identify anomalies and repeat failures. The point is not to smear. The point is to restore proportionality. If a system cannot reliably detect and correct repeat failure, then the court should not treat repeat failure as a surprise. It should treat it as a foreseeable system output.

The sixth step is consequence documentation. This is where the Monitor’s diagnosis matters as governance, not just commentary. If oversight relies primarily on training and coaching without predictable discipline, the system does not self-correct. An integrity-first protocol therefore asks: when improper activation, discontinuity, or missingness occurs, what consequence pathway is triggered? Was it triggered here? Was it triggered before? Were remedial steps imposed? This is not about turning discovery into disciplinary proceedings. It is about determining whether the record system is governed in a way that makes noncompliance costly enough to change behavior. A record system without consequences will always drift toward tolerance of failure, and tolerated failure becomes normalized missingness.

The Integrity-First Disclosure Protocol

| Protocol Step | The Question to the Institution | The Verified Anchor |

| 1. Completeness Map | What cameras should have been recording during the “Pre-Force Window”? | 36% of incidents in the audit were missing footage. |

| 2. Continuity Test | Does the metadata confirm a continuous record, or are there “Integrity Events”? | 18% of footage was activated late or ended early. |

| 3. Handling Record | What do the Intranet Tracker “Progress Notes” say about this specific record? | NYPD already tracks these details internally for FOIL. |

| 4. Review Chain | Who reviewed this force event, and did they document any record-integrity defects? | 53% of oversight logs were missing in audited samples. |

| 5. Pattern Visibility | Is this officer’s “malfunction” part of an aggregated trend of activation failure? | Trend Analysis was found to be “dubious” and unscaled. |

| 6. Consequence Proof | Did this specific record-integrity failure trigger a Consequence Pathway? | Monitor: “Training without discipline” has proven ineffective. |

Once these steps are in place, “prove the record” becomes a court-manageable concept rather than a rhetorical demand. It produces practical results. It forces specificity where institutions often offer generalities. It turns “malfunction” into a proposition that can be tested against integrity artifacts. It turns “we produced everything” into a statement that can be assessed against completeness maps, continuity tests, and handling records. And it turns credibility contests back into what courts are supposed to prefer: proof.

This protocol also solves a problem that too many lawyers accept as inevitable: the fight over discovery becomes an endurance contest. Who will file the motion? Who will appeal the denial? Who has the time and resources to push? A public-access system where disclosure arrives after escalation teaches the same lesson that adversarial discovery can teach: pressure is the pathway to production. An integrity-first protocol pushes against that culture. It says that the pathway to production is not pressure. The pathway to production is governance—documented, auditable, and consistent.

There is also a strategic advantage for the institution in adopting this approach, and it is worth stating plainly because it makes the model credible to a broad audience. Integrity-first disclosure protects officers from false accusations by establishing a reliable chain of evidence. It protects the City from speculative claims by allowing it to prove completeness and continuity when it can. And it protects the legitimacy of policing by reducing the space in which the public suspects that records are curated rather than produced.

If the goal of body-worn cameras was to replace argument with clarity, then the integrity-first protocol is what makes that goal real. Cameras alone do not deliver clarity. A governed record system does. And a governed record system is one that can prove—not merely assert—what happened to the evidence from the moment it was created to the moment it was placed before a court.

That is the point at which audit trails stop being “back office” material and become what they already are in practice: the decisive evidence layer in modern police accountability.

VII. The Public Mirror: FOIL Shows What Happens When the Pipeline Is Allowed to Gatekeep

FOIL is not the center of this thought-piece, but it is the clearest public-facing demonstration of the same institutional dynamic that litigators confront in civil discovery: when the record pipeline controls access, “transparency” becomes something you earn through escalation rather than something you receive as a matter of principle.

The Comptroller’s audit describes a disclosure environment in which body-camera footage is often not produced promptly and in which production frequently arrives only after an appeal is filed or litigation is commenced. That is the key point for the public: the existence of a body-camera program does not guarantee that the public receives body-camera evidence when it matters. The pipeline can delay, deny, and then produce later—often under pressure.

The audit quantifies the delay. NYPD took an average of 133 business days to grant or deny FOIL requests for body-camera footage, and the longest time to grant or deny during the audit period was more than four years—1,076 business days. Those numbers are not minor administrative slippage. They describe a transparency system that is functionally slow enough to defeat the purpose of timely public accountability. A record that arrives after seasons have passed is not “real-time transparency.” It is historical disclosure, often stripped of its ability to influence civic debate when it matters most.

But the most revealing metric is not the delay itself. It is what happens when requesters refuse to accept the first answer. The Comptroller reports that the FOIL appeal process resulted in production 97% of the time, and that court challenges resulted in footage being provided 92% of the time. Those figures matter because they show that escalation is frequently the pathway to disclosure. In plain language: the system often says “no” or “not yet” before it says “yes,” and it becomes far more likely to say “yes” when the requester pushes harder.

That dynamic changes how the public experiences legitimacy. If disclosure depends on persistence, then transparency becomes stratified. People and organizations with time, money, and legal resources can push. Ordinary residents, community journalists, and families often cannot. A system that produces footage primarily after escalation therefore produces a second injustice: unequal access to the public record.

This is also why the audit trail is evidence, not paperwork. The Comptroller’s audit describes how NYPD tracks requests in an internal Tracker database with progress notes, maintains separate tracking for released and denied requests, and tracks appeals through a dedicated log. Those systems reflect that NYPD is not improvising disclosure; it is managing disclosure through a structured pipeline. When that pipeline produces delay and denial, the internal notes and tracking records become the only objective way to understand what happened inside the system and why the requester had to escalate.

For the legal community, FOIL is not a substitute for civil discovery, but it is a warning. A disclosure culture that relies on escalation teaches the same behavioral pattern that litigators see in adversarial cases: partial production, delayed production, and meaningful production only after motion practice. FOIL therefore belongs here as a supporting mirror. It allows the public to see—in a familiar, everyday mechanism—the truth that litigators are trying to explain in court: transparency is not a video file. It is an institutional habit of timely, provable disclosure.

FOIL also clarifies the moral stake of the integrity-first protocol described earlier. If you accept escalation as normal, you accept that “pressure” is the mechanism of truth. That is not a sustainable model for democratic legitimacy. A government agency should not produce records because it fears losing an appeal; it should produce records because the public’s right to know is part of the agency’s duty.

The deeper lesson of Section VII is this: when the pipeline controls access, the pipeline becomes power. And when the pipeline becomes power, the audit trail becomes the only check on that power. That is why audit trails, metadata, and access histories matter to the public even if they never read a discovery demand. Those artifacts determine whether the record is a shared civic resource or a controlled institutional asset.

If the body-camera program was supposed to reduce conflict by producing shared facts, FOIL shows how quickly shared facts turn into negotiated facts when the pipeline is allowed to gatekeep. The solution is not to abandon cameras. The solution is to treat disclosure integrity as a governance obligation—one that can be audited, proven, and enforced—so that the record does not belong to the institution alone, but to the public it serves.

VIII. Reforms That Make the Audit Trail Verifiable: Turning “Tracking” Into Accountability

If the audit trail is evidence, the reform question is not “should we have logs?” NYPD already has tracking systems, progress notes, release/denial tracking, and an appeals log. The question is whether those mechanisms function as accountability infrastructure or as administrative gatekeeping. A pipeline can be meticulously tracked and still produce conditional transparency if the system is designed to tolerate delay, treat missingness as routine, and rely on escalation to trigger meaningful action.

The Comptroller’s audit shows why reform has to be structural, not rhetorical. The audit reports that oversight needs improvement, activation rates are lower than they should be, footage is missing and incomplete, and required reviews and documentation are not consistently conducted or collected. It also reports that footage was not on file for 36% of incidents in the dataset and that late activation or early deactivation occurred 18% of the time where footage was on file. Those findings are not solved by more slogans about transparency. They are solved by designing a record system that generates integrity artifacts by default and treats their absence as a governance failure.

The first reform bucket is mandatory integrity artifacts as non-negotiable outputs. In a mature evidence system, compliance cannot depend on whether a supervisor remembers to complete a review or whether a unit chooses to upload a self-inspection record. Those artifacts must be produced as part of the system’s operation, stored in a way that makes them retrievable, and auditable in a way that makes missingness visible. When self-inspections are missing across more than half of sampled months, the obvious lesson is that a discretionary integrity artifact is not an integrity artifact at all. Reform means making the artifact compulsory and making the absence of the artifact itself a detectable event that triggers command-level accountability.

This reform is not about paperwork fetish. It is about proving integrity in a system where the footage itself cannot be presumed complete. If a court is asked to accept a “malfunction” explanation, the court should be able to see the contemporaneous documentation that the integrity system generated when that malfunction occurred. If the system generates nothing, or the institution cannot produce it, then the explanation is not proven. It is a narrative.

The second bucket is scalable trend analysis as an obligation, not an option. NYPD told auditors that trend analysis of late activation and early deactivation is not accomplished with a data pull and that determining proper activation requires watching entire videos for context, something done ad hoc for ComplianceStat and not scalable to the volume of recordings. The Comptroller found that position dubious and noted auditors were able to aggregate and trend-analyze review results. That dispute reveals a central governance point: scalability is not a defense against accountability. Scalability is a requirement of accountability.

A system that records at scale must be overseen at scale. That means the pipeline must produce routine, periodic trend outputs that identify repeat activation failures, repeat continuity failures, repeat missingness, and repeat disclosure delays. Those trend outputs should not be optional internal memos. They should be standard products of the system, subject to review and capable of being disclosed when integrity is contested. Without trend visibility, every failure will be framed as isolated. With trend visibility, institutions lose the ability to treat repeat failure as misfortune.

The third bucket is independent cross-checking of force-related triggers. The Comptroller reports that NYPD does not independently review body-camera footage to identify use-of-force incidents and does not ensure required TRI reports are filed when force is used, meaning the footage is not reviewed. That reveals a fragile dependency: when integrity review depends on self-reporting, integrity breaks at the precise moment it is most needed. Reform requires independent trigger mechanisms that do not rely solely on whether the involved officers or units properly initiate the review. In practice, this means cross-checking against other internal indicators so that the system can flag incidents for review even when self-reporting fails.

This is not punitive. It is rational. A system cannot promise public trust while relying on the very actors whose conduct may be contested to initiate the integrity review. Independent triggers are how systems protect themselves from predictable human incentives.

The fourth bucket is consequence architecture that treats integrity failures as serious. The Monitor’s reporting is instructive here, not because it is about cameras directly, but because it describes why reforms fail when consequences are inconsistent. The Monitor describes an ongoing lack of meaningful accountability and states that reliance solely on training without discipline has proven ineffective. That lesson applies directly to a camera program. If improper activation is treated as a coaching event, if missingness is treated as a shrug, and if repeat failures are not escalated, the pipeline will keep producing the same integrity defects.

Reform therefore requires predictable escalation. Not discipline for its own sake, but discipline as an engineering feature of compliance. An integrity system must be able to answer a simple question: when late activation, early deactivation, or missing footage occurs, what happens next? And when it happens again with the same officer, unit, or command, what happens then? A pipeline without predictable escalation becomes a pipeline that tolerates failure. And tolerated failure becomes the system’s normal output.

The fifth bucket is disclosure discipline that breaks the escalation habit. FOIL is the supporting mirror here. The Comptroller reports that NYPD took an average of 133 business days to grant or deny FOIL requests for body-camera footage, with the longest taking more than four years, and that appeals and court challenges frequently resulted in production. That is a transparency model that is triggered by pressure. The reform lesson is direct: delay must be treated as a governance defect, not a normal administrative reality.

If the institution’s internal tracking systems are robust enough to document progress notes and categorical decisions, they are robust enough to document time-to-production metrics and to treat prolonged delay as an integrity event. A system that can track requests can measure itself. And a system that measures itself can be held accountable for delay, just as it can be held accountable for activation failures.

The sixth bucket is normalizing audit-trail production as a standard expectation in contested cases. Courts and litigators often treat audit-trail demands as aggressive because they sound technical. The reality is that the institution already creates these artifacts for internal management. Reform means treating production of audit-trail materials as normal when footage is contested, missing, or discontinuous. The public should not have to litigate to learn how the evidence was handled. The integrity materials should be part of routine disclosure when the record is at issue.

The Reform Architecture: From Gatekeeping to Governance

| Reform Bucket | The “Gap” (Oct 2025 Audit Anchor) | The Structural Solution |

| 1. Mandatory Artifacts | 53% missing self-inspections. | Make integrity logs automatic system outputs, not discretionary tasks. |

| 2. Scalable Trends | Trend analysis found “dubious” and unscaled. | Require routine, periodic aggregated trend reports on activation and delay. |

| 3. Independent Triggers | Force footage not reviewed because TRI reports weren’t filed. | Cross-check BWC review against Dispatch and Medical response logs to flag force events. |

| 4. Consequence Architecture | Monitor: “Training without discipline” is ineffective. | Build a predictable escalation ladder for repeat activation and continuity failures. |

| 5. Disclosure Discipline | 133-day average FOIL delay; 97% reversal on appeal. | Treat delay as a governance defect and measure “Time-to-Production” as a key performance metric. |

| 6. Normalized Audit Trails | Internal tracking exists but is used as a gatekeeping tool. | Standardize the production of Handling Proof whenever a record is contested in court. |

This is the point where reform becomes conceptually simple. A body-worn camera program is either an accountability system or it is a legitimacy system. An accountability system produces verifiable integrity artifacts, measures itself at scale, cross-checks triggers independently, enforces compliance with predictable consequences, and discloses without requiring escalation. A legitimacy system does the opposite: it records sometimes, explains gaps with untestable narratives, produces transparency late, and relies on internal tracking as a gatekeeping tool rather than as an accountability instrument.

The Comptroller’s findings about missingness, discontinuity, and inconsistent oversight show why the choice matters. The Monitor’s diagnosis about accountability and the limits of training-only reform explains why the choice cannot be left to goodwill. Governance must be built into the pipeline. Otherwise the audit trail remains what it too often becomes in practice: a record of how the institution managed access, not a record that proves the institution can be trusted with the evidence of its own power.

IX. Closing: The Audit Trail Is Where Legitimacy Lives Now

Body-worn cameras were supposed to settle disputes by replacing argument with proof. That promise was always incomplete, because it assumed technology could substitute for governance. A camera can record what happens in front of it. It cannot guarantee that recording exists when it should, continues when it must, is preserved as a complete artifact, and is produced without delay or negotiation. Those guarantees come from systems—rules, oversight, trend visibility, and consequences—and those systems are only as credible as the integrity artifacts they generate.

The Comptroller’s audit makes the record-integrity problem impossible to minimize. It reports that footage was not on file for 36% of incidents in the dataset and that, where footage was on file, late activation or early deactivation occurred 18% of the time. It also reports inconsistent oversight: self-inspections for activation missing for 53% of sampled months, and limited aggregation to identify anomalies and trends. These are not abstract weaknesses. They are the structural conditions that turn trials into credibility contests. When the record is missing or discontinuous, the factfinder does what human beings always do: fills the gap with inference. And in police cases, inference is rarely neutral.

FOIL shows the public-facing version of the same dynamic. When disclosure becomes slow and frequently requires escalation, transparency starts to function like a negotiation rather than a duty. The public learns—explicitly or implicitly—that “access” depends on persistence, resources, and procedural stamina. The institution learns the same lesson from the other side: delay reduces pressure, and escalation narrows the pool of people who can keep pushing.

This is why the audit trail is no longer secondary. It has become the decisive evidence layer. In a world where the footage cannot be presumed complete, the only reliable way to test an institution’s account is to test the institution’s handling of the record: what should exist, what exists, how it was categorized, how it was reviewed, how it was tracked, how it was escalated, and what happened when integrity failed. That is what the audit trail captures. It is not administrative residue. It is the modern chain of legitimacy.

The Monitor’s warning about accountability underscores why this cannot be left to goodwill. When systems rely primarily on training without meaningful consequences, noncompliance persists and reforms flatten into performance. The same is true of record integrity. If late activation, early deactivation, missing footage, or missing integrity documentation does not trigger predictable escalation and consequences, then the pipeline will continue to produce the same defect: conditional truth.

So the closing claim of this thought-piece is not anti-camera. It is anti-illusion. The question is not whether NYPD has body-worn cameras. The question is whether NYPD can prove record integrity when the stakes require proof. A camera program that cannot consistently produce completeness, continuity, and auditable handling cannot deliver the legitimacy benefits cameras were sold to provide.

The way forward is conceptually simple even if administratively demanding: stop treating “the video” as the accountability and start treating “the record system” as the accountability. Demand integrity artifacts as a matter of course. Normalize integrity-first disclosure when footage is missing or discontinuous. Build trend visibility that identifies repeat failures rather than explaining them away. And create consequence architecture that makes record integrity a constitutional obligation rather than an administrative preference.

In 2026, legitimacy does not turn on whether a camera exists on a uniform. It turns on whether the City can prove—step by step—what happened to the evidence after the encounter ended. If the City can prove the record, the public gets something rare in police accountability: shared facts. If the City cannot prove the record, the camera becomes what it too often is today: a device that records enough to claim transparency, but not enough to guarantee it.

That is the choice. And the audit trail is where the choice becomes visible.

X. Reader Toolkit / Practical Checklist: How to “Prove the Record” Without Guesswork

This toolkit is designed to be usable by two audiences at once: the public trying to assess whether transparency is real, and lawyers trying to test record integrity in an adversarial setting. The principle is the same in both contexts: do not argue about what a clip “means” until you have proven what the record is.

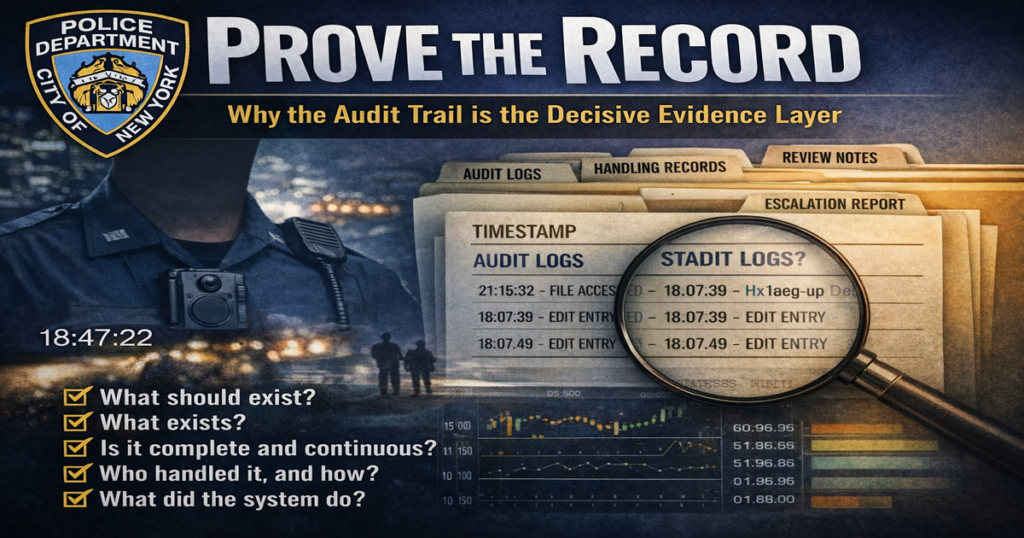

A. The Five Integrity Questions (the one-minute test)

What should exist?

What exists?

Is what exists complete and continuous?

Who handled it, and what did they do with it?

What did the system do when integrity failed?

If any answer is “we can’t tell,” the system is not delivering transparency; it is delivering narrative.

B. Public Toolkit: Questions That Expose Conditional Transparency

Existence: Which officers or units were involved, and how many recordings should exist for the event window?

Completeness: Does the footage show the full encounter from the earliest relevant moment through resolution, or does it start late/end early?

Continuity: Are there gaps, abrupt stops, muted segments, or missing context? If yes, what contemporaneous record explains why?

Timing of disclosure: When did the requester ask, and when did the requester receive the footage?

Escalation: Was the footage produced only after an appeal or court pressure? If yes, what changed between the first decision and the eventual production?

Consistency: If the system says “this was a one-off,” what records exist to prove it was not a repeat pattern?

C. Litigation Toolkit: Integrity-First Discovery Checklist (Plain English, Court-Usable)

Completeness Map (who/when):

Identify every member/unit reasonably expected to have been present and define the time window that must be covered (pre-contact → force → aftermath). Demand a definitive statement of all recordings located and all recordings not located for that window, with the reason for nonexistence.

Continuity Proof (start/stop):

Treat late activation and early deactivation as integrity defects that require documentation. Demand the full narrative arc—do not accept curated fragments as “the encounter.”

Handling Record (the pipeline file):

Demand the internal handling records that show how the footage moved through the system—tracking notes, release/denial determinations, and any escalation records—so the institution cannot substitute explanation for proof.

Review Chain (who reviewed and when):

Demand documentation of required internal reviews triggered by the incident and triggered by any recording deficiencies. If the institution claims it reviewed or audited, require the record of that review.

Pattern Visibility (repeat failures):

Demand whether the system aggregates activation/continuity failures and whether the involved members/units appear in repeat-failure patterns. Isolated-incident framing should not be accepted where the system can test repeat behavior.

Consequence Proof (what happened next):

Demand documentation of corrective actions triggered by integrity failures and whether repeat failures triggered escalation beyond retraining. A system without consequences does not self-correct.

Production Integrity (completeness of production):

Demand confirmation that production represents the complete set of responsive recordings for the defined window and participants—not a curated selection—along with the internal basis for that confirmation.

D. The “Credibility Trap” Warning (Why This Toolkit Exists)

When the record is missing or discontinuous, the case becomes a credibility contest. Credibility contests are where institutional power tends to win. The only reliable counterweight is an integrity method that forces proof of what exists, what is missing, why it’s missing, and how the system handled the evidence.

E. The Core Takeaway

“Produce the video” is not the accountability demand.

“Prove the record” is.

Reader Supplement

To support this analysis, I have added two companion resources below.

First, a Slide Deck that distills the core legal framework, case law, and institutional patterns discussed in this piece. It is designed for readers who prefer a structured, visual walkthrough of the argument and for those who wish to reference or share the material in presentations or discussion.

Second, a Deep-Dive Podcast that expands on the analysis in conversational form. The podcast explores the historical context, legal doctrine, and real-world consequences in greater depth, including areas that benefit from narrative explanation rather than footnotes.

These materials are intended to supplement—not replace—the written analysis. Each offers a different way to engage with the same underlying record, depending on how you prefer to read, listen, or review complex legal issues.

Related