Executive Summary

This thought-piece reads the dispute in the order the law requires: first the First Amended Complaint, then the DRPG arbitration ruling. In that sequence, the story is not one hiring outcome. It is a civil-rights governance dispute over the decisive question—who controls the forum and, with it, the rules that govern discovery, record-making, and review.

The amended complaint is framed as a systemic challenge. It alleges race-based exclusion across hiring, retention, and termination inside a leaguewide employment system. That framing shifts the inquiry away from personalities and toward the pressure points: where discretion sits, what gets recorded (and what doesn’t), how “compliance” is performed, and whether procedure is being used to bless outcomes that were effectively set in advance.

The prayer for relief confirms that this is a redesign case, not just a damages case. Plaintiffs seek objective criteria, disciplined evaluation records, and transparency tools—and, critically, an end to forced arbitration for discrimination and retaliation disputes. That is not an add-on. It is the complaint identifying the choke point.

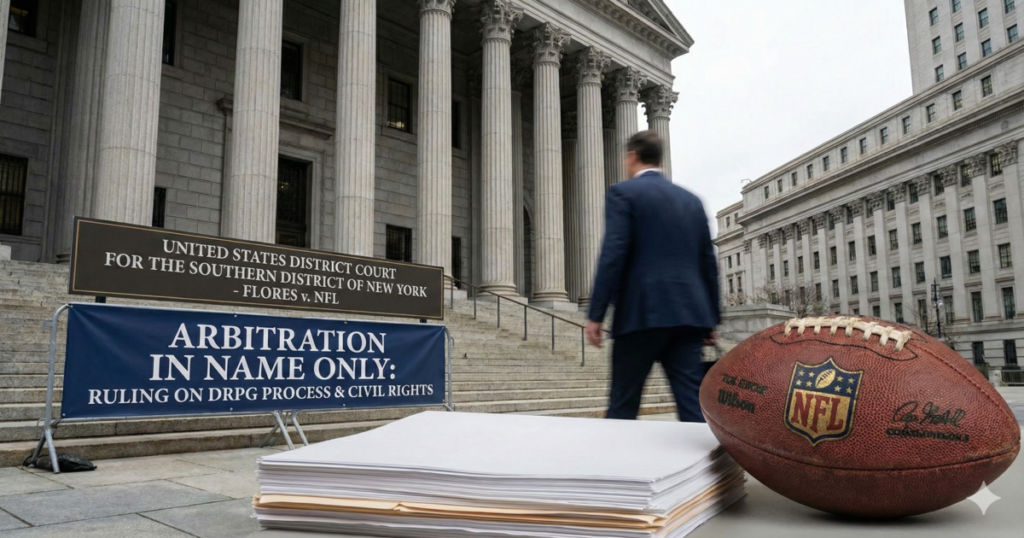

The February 13, 2026 arbitration order is the turning point because it answers the power question: public court or private system. The court denied the motion to compel arbitration in full. That is not scheduling. It is forum allocation—and in civil-rights litigation, forum allocation often determines the practical force of the right long before anyone reaches the merits.

DRPG sits at the center of that decision. The NFL’s Dispute Resolution Procedural Guidelines were offered as the solution to neutrality concerns. The court disagreed—because the defect was designed into the ruleset: independence, mutual process, amendment opacity, emergency-relief uncertainty, conflict controls, and review ambiguity. The same problem kept resurfacing: concentrated institutional control over the dispute system.

The thesis is simple: labels don’t decide enforceability; structure does. Calling something “arbitration” does not make it a neutral forum for statutory rights. In discrimination litigation, the forum can narrow the claim—compress discovery, limit public accountability, and constrain meaningful review—before the merits are ever tested.

So this piece proceeds as legal analysis, not commentary: what the amended complaint alleges and why it is framed as system litigation; what the DRPG ruling actually tests; and why the result matters far beyond football for any institution relying on privately controlled dispute systems to adjudicate public-law rights.

If the forum is controlled, the right is subject to conditions.

I. Introduction: Start With the Pleading, Not the Commentary

If this case is going to be analyzed with any legal seriousness, it has to be read in the order the law reads it: pleading first, procedural rulings second, narrative last. Public conversation tends to reverse that sequence. It starts with reaction, moves to personalities, and then backfills legal meaning. That is exactly backward. In civil-rights litigation—especially in high-visibility employment systems—early framing errors produce strategic errors later: wrong discovery targets, wrong assumptions about burden, and a distorted view of what the court is actually being asked to decide.

The thesis of this thought-piece is straightforward: this is a system-design case, not a headline case. The core dispute is not reducible to a single interview, a single employer decision, or a single plaintiff narrative. The pleading posture and requested relief make clear that plaintiffs are challenging an institutional model—how hiring authority is exercised, how retention and termination decisions are structured, how “compliance” is documented, and how dispute mechanisms can either preserve statutory enforcement or blunt it. Once you see the design problem, the arbitration fight stops looking like a detour and starts reading like the leverage point.

That methodology matters. We begin with the First Amended Complaint because it defines the legal theory, the proof horizon, and the remedial target. Pleadings are not just formalities; they are architecture. They tell you what facts will matter, what conduct is alleged, and what legal pathways are being invoked. They also signal whether plaintiffs are primarily seeking individual redress or institutional reform. Here, the pleading is aimed at the latter. It is designed to test whether anti-discrimination law can operate effectively inside a private labor market where discretion is expansive, transparency is uneven, and policy language can operate both as protection and as shield.

Only after that do we proceed to the arbitration order and the DRPG analysis. That sequence is deliberate. If you start with the order, arbitration can look like a technical waypoint. It is not. In this litigation, forum allocation is a control question: who decides, under what procedural constraints, with what neutrality safeguards, and with what review structure. Those features determine practical enforceability long before the merits are fully briefed, let alone tried. In civil-rights cases, procedure and substance do not live in separate silos. Process design often decides what “rights” are available in real life.

The stakes, therefore, exceed any single industry dispute. Forum control is often outcome control in civil-rights litigation. A public-law claim routed into a privately controlled system can remain valid in doctrine while shrinking in real-world force. Conversely, keeping statutory claims in a public judicial forum preserves transparency, precedential constraint, and a fuller mechanism for evidentiary development and legal review. That is why this thought-piece treats the amended complaint and the arbitration order as one continuous legal sequence: first, plaintiffs allege structural discrimination; second, the court tests whether the proposed private forum can credibly adjudicate those rights.

This framing also clarifies what this thought-piece is not doing. It is not resolving disputed liability facts. It is not converting allegations into findings. And it is not performing sports commentary with legal vocabulary attached. It is doing something more demanding: tracing the legal logic from pleading theory to forum ruling—and showing why that progression matters for civil-rights enforcement beyond this case.

The roadmap is simple. Section II reads the amended complaint as structural litigation—parties, class posture, systemic theory, and the institutional design claims embedded in the requested relief. Later sections then examine the DRPG ruling as a stress test of private dispute architecture: whether the ruleset can support statutory enforcement without collapsing neutrality or undermining effective vindication. Read this way, the case is neither episodic nor personality-driven. It is a governance dispute about control over process.

And control over process is often control over outcomes.

II. The Amended Complaint as Structural Litigation

The amended complaint is drafted to do more than recount adverse events. It is built to establish a system-level theory of discrimination across hiring, retention, and termination. That distinction is decisive. A conventional adverse-action case asks whether one decision was unlawfully motivated. A structural case asks whether the decision environment itself is configured to predictably produce exclusion while preserving managerial deniability. The plaintiffs’ posture, claim construction, and requested remedies read as the latter.

A. Parties and Class-Representative Posture

At the most basic level, party structure signals litigation ambition. Plaintiffs are positioned not merely as individual claimants but as class representatives, and defendants include both league-level and club-level actors. That arrangement is not cosmetic. It reflects an allegation that discriminatory outcomes are not confined to a single workplace node; they arise from interacting levels of authority—league governance, club discretion, and shared decision norms.

That multi-level design has immediate practical consequences. It expands discovery beyond plaintiff-specific files to include league–club communications, governance interfaces, comparative decision data, and process documentation across entities. It also undermines the standard compartmentalization defense (“one team,” “one owner,” “one year”). By pleading across institutional layers, plaintiffs force the litigation to test whether apparent fragmentation is real—or whether it operates as cover for a coherent pattern of exclusionary practice.

B. Systemic Discrimination Theory Across Hiring, Retention, and Termination

The complaint’s theory is not limited to point-of-entry hiring. It links hiring access, retention security, and termination vulnerability as interconnected stages of a single employment system. That matters because discrimination in elite labor markets rarely presents as a single gate denial. More often, it shows up as a sequence: constrained access to top roles, heightened scrutiny once inside, a shorter runway, and differential tolerance for performance variance.

By pleading across all three stages, plaintiffs avoid the narrow trap of litigating one hiring decision detached from the career lifecycle. They can argue that the harm is cumulative and structural: unequal opportunity is reproduced through recurring discretionary judgments that look individualized in isolation but read as a pattern when assessed longitudinally.

This approach also shifts the evidentiary center of gravity. Instead of depending solely on direct evidence tied to a single decision-maker, structural pleading invites comparative proof, statistical context, chronology, and policy–practice divergence. It also foregrounds the questions that drive systemic cases: Who receives repeat opportunities? Who is labeled “ready”? Who is treated as “high risk”? Who is retained through adversity? Who is displaced quickly? In this posture, those questions are not rhetoric—they are proof pathways.

C. Why This Is Broader Than Individual Adverse Actions

A common defensive move in employment litigation is atomization—treat each event as an isolated managerial judgment. Structural pleading rejects atomization. It alleges that outcomes are produced by repeatable institutional conditions: opaque criteria, inconsistent documentation, concentrated discretion, and compliance frameworks that can be satisfied formally while underdelivering substantively.

That framing is especially potent where institutions are policy-rich. Formal policy language can create an appearance of fairness that obscures operational disparity. The plaintiffs’ theory, as framed, is that process form and process function may diverge. A system can generate procedural artifacts—interviews, checklists, policy statements—without delivering equal opportunity in practice. When that divergence is placed in issue, the inquiry shifts from whether rules exist to how they are applied, by whom, with what consistency, and with what measurable outcomes.

This does not collapse into a claim that every unfavorable outcome is discriminatory. Structural pleading still demands disciplined proof. But it properly centers what systemic litigation is designed to test: whether institutional design features create predictable asymmetry that individual narratives alone cannot capture.

D. Leaguewide Context and Institutional Design

The complaint’s leaguewide framing does significant legal work. It situates decisions within a shared governance and cultural environment rather than treating each club as a sealed silo. Even where clubs retain formal autonomy, institutional ecosystems can still harmonize behavior through norms, incentives, informal signaling, and reputational risk management. Structural litigation is designed to test those cross-entity dynamics.

Institutional design analysis in this setting typically turns on five domains: (1) selection criteria—specific, stable, and auditable versus malleable and post hoc; (2) contemporaneous documentation—whether reasons are recorded in real time and in comparable form; (3) comparator control—whether similarly situated individuals are evaluated under consistent baselines; (4) governance interfaces—how league-level policy interacts with club-level discretion in practice, not just on paper; and (5) audit and enforcement—whether meaningful checks exist to detect and correct pattern-level inequities.

A structural complaint need not prove each domain at the pleading stage. It must plausibly place them in issue. This complaint does so by linking allegations to broader employment architecture and by seeking remedies aimed at systemic correction rather than isolated compensation.

E. Strategic Implications of Structural Pleading

Treating the amended complaint as structural litigation has immediate consequences for case management and advocacy.

For plaintiffs, it supports broader, integrated discovery and reinforces remedies aimed at preventing recurrence.

For defendants, it increases the cost of fragmented narratives and heightens pressure to demonstrate operational consistency—not merely the existence of policy.

For the court, it puts early procedural choices—especially forum allocation—on the merits-adjacent side of the line because those choices determine whether systemic proof can be developed in a credible way.

That final point bridges directly to the arbitration section. Once a complaint is properly understood as a system-design challenge, the forum question cannot be minimized. If systemic rights are to be vindicated, the adjudicative forum must be capable of handling systemic proof. That is why the DRPG ruling matters: it sits on top of the pleading’s core theory.

F. Section Conclusion

The amended complaint should be read as a deliberate attempt to move the case from anecdote to architecture. Its party structure, lifecycle discrimination theory, and system-focused remedial posture collectively reject the notion that this litigation concerns one disputed employment call. It targets whether institutional design can generate unequal outcomes while insulating those outcomes behind procedural form.

That is the right place to start. Because once you see the complaint this way, the arbitration fight is no longer a side issue—it becomes the next stage in a larger contest over who controls civil-rights enforcement: public court under public-law constraints, or private process under concentrated institutional control.

III. What Plaintiffs Allege, Precisely

The amended pleading is strongest when read as an allegation about institutional mechanics, not merely institutional motive. Put plainly: this is not only a claim that adverse outcomes occurred; it is a claim that the decision environment was structured so inequitable outcomes were predictable, defensible, and hard to audit in real time. That is why precision matters. When critics dismiss the complaint as “headline litigation,” they miss what the pleading is doing: it identifies how process can be used to generate the appearance of fairness while preserving the discretion that defeats equal opportunity in practice.

A. Rooney Rule Context: The Process–Substance Fault Line

The Rooney Rule exists because professional football acknowledged a representation crisis in leadership pipelines. On paper, it creates procedural obligations—interview requirements and related hiring-process expectations. The complaint raises the harder question: what happens when the procedure is satisfied on paper but defeated in function?

That is the process–substance fault line. Process asks whether steps occurred. Substance asks whether those steps were meaningful vehicles for competitive consideration. A system can be process-rich and equity-poor at the same time if interviews are scripted, criteria are elastic, comparative assessments are undocumented, and the decisive judgment is effectively made outside the formal window.

The pleading places that tension at the center of the case. It contends that compliance artifacts can be produced without compliance outcomes. That allegation matters because civil-rights enforcement is not designed to reward procedural theater; it is designed to ensure equal access, equal consideration, and non-discriminatory outcomes under legitimate, consistently applied standards.

And the litigation consequence is straightforward: if plaintiffs can show that the process was structurally incapable of changing outcomes—or was used to insulate outcomes already set—then “we followed the process” is not a defense. It becomes the opening question: what was the process designed to accomplish, and for whom?

B. Horton as Case Study: Alleged Sham Interview and Performative Compliance

The Horton allegations operate as a test case for the complaint’s broader structural thesis. The claim is not merely that Horton was not hired; it is that the interview functioned as a compliance artifact—formal completion rather than good-faith evaluation. In plain terms, the process is alleged to exist to certify optics, not to create a real competitive pathway.

That matters because sham-process allegations expose the gap between eligibility to interview and eligibility to be meaningfully selected. Anti-discrimination law is not satisfied by symbolic access to a room where the decision has already been made elsewhere. The law tests opportunity quality, not opportunity symbolism.

The proof design follows from that theory. A sham interview allegation is typically tested through chronology, internal communications, comparator interview treatment, pre-interview decision signals, consistency of evaluative documentation, and post-hoc rationale formation. If those categories show the outcome was effectively locked before the formal process concluded, the “procedure” becomes evidence of discriminatory infrastructure rather than neutral decision-making.

That is what “performative compliance” means here: rule-following that is externally legible as compliant but internally organized to preserve preferred outcomes. It can be harder to prove than overt exclusion, but when proven it is more consequential, because it implicates governance design across cycles—not a single employment decision.

C. Federal and State/Local Claim Architecture: §1981 at the Core

The complaint’s legal architecture is deliberate. Section 1981 sits at the core because it provides a federal framework for race-based discrimination in contractual and employment opportunity structures. In a case alleging systemic exclusion in elite hiring and retention pathways, § 1981 is not decorative—it is the doctrinal spine tying decision practices to enforceable federal rights.

Around that federal core, the pleading layers state and local anti-discrimination frameworks. Strategically, that does two things: it prevents the case from being reduced to one doctrinal lane, and it preserves parallel enforcement pathways where standards, burdens, and remedies may operate differently.

The practical implication is also plain: institutions cannot rely on a single rebuttal narrative across layered civil-rights claims. A defense that sounds adequate under one framework may fail under another depending on comparator analysis, causation structure, or remedial scope. That is why systemic cases are often pleaded this way—not for redundancy, but for enforcement resilience.

D. Pleading-Level Implications for Discovery Scope

If the complaint is structural, discovery must match the structure. Narrow, incident-only discovery would be analytically inconsistent with allegations targeting the system’s design. The pleading-level implications are concrete:

- Comparator breadth matters. Plaintiffs will seek similarly situated decision cohorts across hiring cycles, retention windows, and termination events—not isolated files.

- Documentation timing matters. Contemporaneous records distinguish real-time rationale from litigation-stage reconstruction.

- Decision chronology matters. Sequence analysis can reveal whether the formal interview occurred before or after the practical decision was already made.

- Criteria stability matters. Plaintiffs will test whether selection standards were pre-defined, consistently applied, and auditable across candidates.

- Cross-entity communications matter. In a leaguewide context, governance signals may travel through formal and informal channels.

- Policy–practice divergence matters. The existence of a policy is not endpoint proof; operational fidelity is.

That discovery design is not overreach. It is proportional to the pleaded theory. A systemic claim cannot be tested with an anecdotal record.

E. Proof Design: From Anecdote to Pattern

The pleading’s precision also previews proof strategy. In structural cases, plaintiffs typically build a layered evidentiary stack: narrative evidence, comparative evidence, chronological evidence, documentary evidence, and institutional evidence. No single layer is usually sufficient. The strength comes from convergence—independent lines of proof pointing to the same conclusion: that the process was constrained in function and managed through discretionary opacity.

Defendants often respond with fragmentation: isolate each event, narrow comparators, emphasize policy language, and reframe discretion as merit judgment. That approach can succeed in incident-only litigation. It is less reliable when plaintiffs build a pattern record that links decisions across time and governance levels.

F. Why Precision at Pleading Stage Is Strategic, Not Cosmetic

In system cases, detail is not rhetoric; it is discipline. Precision at pleading stage serves four strategic functions:

- It anchors discovery in mechanism, not general allegation.

- It constrains evasive defenses by specifying how the system is alleged to operate.

- It preserves remedy arguments aimed at recurrence prevention.

- It frames forum disputes—including arbitration—as rights-enforcement questions rather than procedural housekeeping.

That last point matters here: once plaintiffs allege systemic process distortion, the forum becomes merits-adjacent. A constrained forum can neutralize structural claims by compressing discovery, limiting transparency, or embedding asymmetrical procedural controls. That is why complaint precision and forum litigation are connected chapters of the same strategy.

G. Section Conclusion

What plaintiffs allege is not simply discriminatory outcome; it is discriminatory infrastructure: a process environment where formal compliance can coexist with substantive exclusion, where interviews may function as optics, where discretion can be shielded by policy language, and where enforcement therefore must examine design—not just discrete acts.

That is the value of reading the pleading carefully. It shows the case is not about whether a rule existed. It is about whether the rule had operational integrity when it mattered.

IV. Prayer for Relief as a Governance Blueprint

In most public discussions, the prayer for relief is treated as boilerplate at the end of the complaint. In structural civil-rights litigation, that is a costly misread. The remedies section often tells you more about the case’s true ambition than any press statement ever could. Here, the requested relief is not framed as a one-time monetary correction. It reads as a governance blueprint aimed at changing institutional behavior going forward.

A. Structural Remedies Sought: Rewiring Decision Architecture

The relief framework seeks mechanisms to convert a culture of discretionary decision-making into an auditable decision-making practice. That includes objective criteria, documented evaluation systems, and transparency tools designed to make opportunity allocation verifiable rather than impressionistic.

These remedies do not eliminate managerial judgment; they discipline it. That distinction is legally and operationally important. Anti-discrimination law does not require institutions to abandon discretion altogether. It requires that discretion not operate as a covert channel for prohibited bias. Structural remedies target that risk by imposing process-integrity conditions:

Objective criteria constrain post-hoc rationalization;

Written evaluations create contemporaneous accountability;

Comparative tools reduce arbitrary asymmetry;

Transparency mechanisms allow pattern detection before a litigation crisis.

In other words, the remedy logic matches the liability logic: if an opaque and malleable process produces harm, remediation must increase clarity, consistency, and traceability.

B. Why the Anti-Arbitration Relief Request Is Central

One of the most strategically significant aspects of the prayer for relief is the request that the court bar forced arbitration of discrimination and retaliation claims. This is not a side issue. It is central to whether statutory rights are enforceable in practice.

When plaintiffs seek anti-arbitration relief in a structural discrimination case, they are making a governance claim: private forum design can function as a mechanism for constraining enforcement—through reduced transparency, limited precedent, asymmetrical procedural leverage, and diminished public accountability.

In this case, that relief request became especially consequential once arbitration moved to the forefront through DRPG-related litigation. The sequence matters. Plaintiffs did not add forum concerns as an afterthought once the dispute escalated; they embedded forum governance in the remedial design from the outset of the complaint. That coherence strengthens the argument that forum control and merits enforcement are inseparable here.

C. Individual Compensation vs. Institutional Redesign

A robust prayer for relief distinguishes between two categories of remedy that are often conflated:

Individual compensation remedies (back pay, front pay, compensatory or punitive frameworks where applicable); and

Institutional redesign remedies (rules, documentation standards, monitoring structures, and process constraints aimed at recurrence prevention).

Compensation answers: how do we address harm already suffered?

Redesign answers the harder question: how do we prevent repetition under the same governance model?

The complaint’s relief framework indicates that plaintiffs seek both—while recognizing that compensation alone does not cure structural exposure. Institutions can pay claims and preserve the same decision system that produced them. Structural remedies are the mechanisms aimed at breaking that cycle.

D. Governance Blueprint as Litigation Signal

Courts and defendants read prayers for relief as strategic signals. A narrow damages-only demand often invites narrow settlement logic: price the claim, close the file, preserve the system. A governance-focused demand changes the negotiation terrain. It puts process legitimacy on the table and raises reputational, operational, and compliance stakes beyond immediate damages calculus.

That signaling function matters in high-visibility industries. Once plaintiffs seek measurable structural reforms, institutional defendants must decide whether to defend design choices publicly and under discovery pressure. For many organizations, that is a more consequential risk than the monetary component of a single case.

E. Operational Implications of a Governance-Oriented Remedy Model

If courts take governance-oriented remedies seriously, institutions face practical implementation choices:

Define stable, role-specific selection criteria;

Require contemporaneous written rationale at each key decision step;

Establish comparator review protocols;

Track outcome disparities across cycles;

Formalize conflict safeguards in dispute processes;

Build independent oversight with clear authority and audit rights.

These are not performative commitments. They are operational controls. Their function is to reduce legal exposure by reducing structural ambiguity—the space where bias can be exercised without detection and later defended as “discretion.”

F. Section Conclusion

The prayer for relief should be read as the complaint’s enforcement philosophy in compact form. It does not just seek damages; it seeks redesign. It treats discrimination risk as an institutional systems problem requiring institutional systems correction. And by placing anti-arbitration relief within that framework, it identifies forum control as part of the architecture of harm—not merely the architecture of adjudication.

That is why this remedies section matters: it tells the court—and the public—that the goal is not to litigate a headline. The goal is to change the machinery that makes the headline predictable.