Executive Summary

This thought-piece addresses a persistent and consequential misunderstanding about police speech: the belief that the New York City Police Department may preclude, chill, or punish speech by fraternal organizations because their members are police officers. That belief is legally wrong, structurally unsound, and constitutionally dangerous.

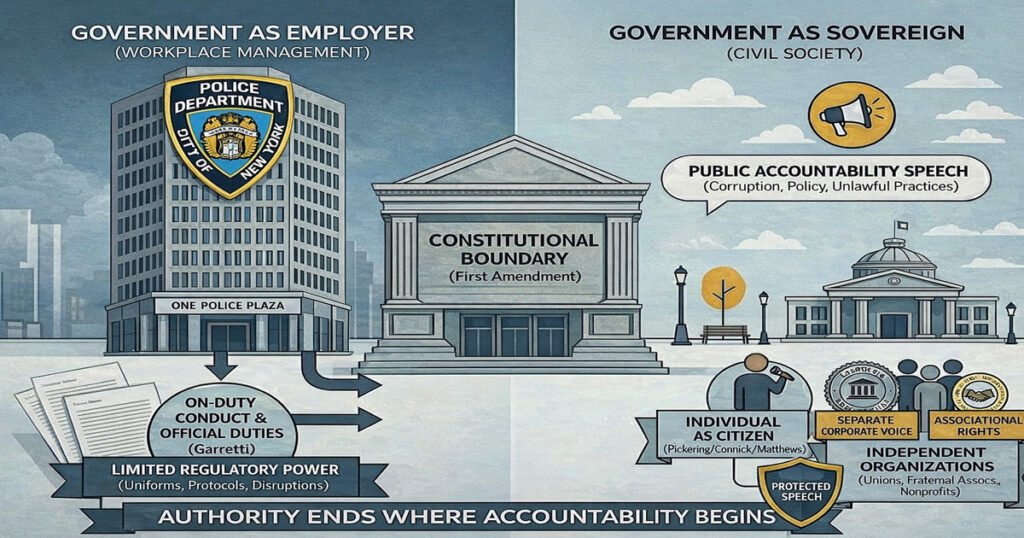

At its core, the error arises from a failure to distinguish between government authority over employees and government power over independent speakers. The NYPD, like any public employer, possesses limited authority to regulate on-duty conduct and speech made pursuant to official duties. What it does not possess is a general license to suppress criticism of its own practices by recasting independent organizational speech as employee misconduct.

This essay explains why that distinction matters, how it is repeatedly blurred in practice, and why the blurring is institutionally useful to government actors seeking to avoid accountability.

The analysis begins with first principles. Public-employee speech doctrine—rooted in cases such as Pickering v. Board of Education and Connick v. Myers—recognizes that the government wears two hats: employer and sovereign. When the government acts as an employer, it may impose narrow speech restrictions tied to workplace function. When it acts as a sovereign censor, however, it is bound by the full force of the First Amendment. The Constitution does not permit the state to convert sovereign censorship into managerial discipline by relabeling speech.

The Second Circuit’s decision in Matthews v. City of New York is central to this analysis. Matthews rejects the overextension of Garcetti v. Ceballos and makes clear that speech criticizing policing practices—such as arrest quotas—is not automatically unprotected simply because it comes from a police officer. Critically, Matthews establishes that even individual officers retain First Amendment protection when speaking as citizens on matters of public concern. That holding sets a constitutional floor.

From there, the essay moves to corporate separateness. Labor unions and fraternal organizations are not employees; they are separately incorporated legal entities with independent governance, institutional voice, and associational rights. When such organizations speak, they do so as corporations, not as extensions of the NYPD’s chain of command. The Department does not employ these entities, does not assign them duties, and does not possess disciplinary jurisdiction over them. Any attempt to control or suppress their speech is therefore not an exercise of employer authority—it is state action directed at a private speaker.

The essay then examines how suppression actually occurs in practice. Rarely does it take the form of explicit gag orders. Instead, it appears as viewpoint discrimination disguised as “neutral discipline,” and as retaliation by proxy—where pressure is applied to individual members in order to chill organizational speech. Supreme Court precedent makes clear that such indirect retaliation is constitutionally indistinguishable from direct censorship, and that chilling association is itself a First Amendment injury.

Importantly, the essay also delineates what the NYPD can lawfully regulate: on-duty conduct, speech pursuant to official duties, neutral time-place-manner restrictions, and genuinely disruptive behavior supported by concrete evidence. These powers are real—but they are narrow by design. They exist to ensure operational integrity, not to shield institutions from criticism or suppress speech about corruption, discrimination, or unlawful employment practices.

Finally, the essay explains why this confusion persists. Blurring the line between employee speech and organizational speech benefits institutions. It allows suppression to be reframed as management, constitutional scrutiny to be avoided, and accountability to be delayed or denied—often before discovery ever begins. The result is a chilling effect on civil society and a distorted application of First Amendment doctrine.

The central conclusion is straightforward: the NYPD’s authority ends where independent organizational speech begins. The Department may manage its workforce, but it may not manage dissent in civil society. When fraternal organizations or unions speak on matters of public concern, especially about corruption or unlawful employment practices, attempts to silence or retaliate against that speech violate the First Amendment’s most basic protections.

This is not a pro-police or anti-police argument. It is a pro-constitutional one. The same rules that protect police-affiliated organizations today protect teachers, doctors, engineers, and other public servants tomorrow. In a constitutional democracy, accountability is not a threat to authority—it is its necessary limit.

I. Introduction: The Persistent Misunderstanding About Police Speech

There is a recurring error that shows up in three places at once—inside police departments, in public commentary, and in the way even sophisticated observers talk about “speech by police.” The error is the assumption that because police officers are employees of the NYPD, any organization made up of police officers can be treated as if it is subject to NYPD control over what it says. That assumption collapses constitutional boundaries, distorts doctrine, and—most importantly—invites institutional overreach under the false comfort of “employment authority.”

This thought-piece is not about whether speech is polite, prudent, politically convenient, or good for morale. It is about power: who has it, what kind of power it is, and where it stops. The NYPD has real authority over on-duty conduct and over the workplace. But that authority is not a general license to suppress criticism, and it is not a transferable weapon that can be pointed at any speaker the Department finds embarrassing. When a government agency tries to silence an independent voice by calling it “employee speech,” the First Amendment issue is not subtle: the agency is trying to re-label censorship as supervision.

The confusion persists because the NYPD is not just any employer. It is a government employer with a paramilitary culture, a public-safety mandate, and a command-and-control operational model. Those institutional features create a temptation to treat speech as another form of “order.” The impulse is familiar: if the Department can regulate uniforms, patrol assignments, radio discipline, and use-of-force protocols, why not regulate the narrative too? The problem is that narrative control is not a managerial function in a constitutional democracy. It is the very thing the First Amendment is designed to restrain when it is exercised by the state.

To write credibly about this topic, you have to separate three things that get blended together in practice:

First, individual officers sometimes speak “as employees”—pursuant to job duties, inside the chain of command, performing or purporting to perform official functions. That category triggers one set of doctrines.

Second, individual officers sometimes speak “as citizens”—outside job duties, on matters that the public has a legitimate stake in, including the governance of policing itself. That category triggers a different analysis.

Third, organizations composed of officers—unions, fraternal associations, benevolent organizations, advocacy nonprofits—speak “as organizations,” meaning they speak through separate governance, separate institutional voice, and separate legal identity. That category is the one most people intuitively misunderstand, and it is the category that tends to expose the greatest institutional appetite for overreach.

When critics say, “The Department can shut them up because they’re cops,” what they are doing is collapsing all three categories into one. It is a doctrinal shortcut that assumes the conclusion: “they’re cops, therefore it’s employee speech, therefore the NYPD can control it.” But the Supreme Court’s public-employee speech jurisprudence does not work that way, and—more importantly—the Constitution’s structural limits on state censorship do not work that way.

This misunderstanding is not academic. It changes real-world outcomes.

If organizational speech is wrongly treated as “employee speech,” the Department gains an easy rhetorical tool: it can frame suppression as discipline. It can call criticism “insubordination.” It can describe public accountability speech as a threat to “unit cohesion.” It can substitute internal norms for constitutional standards. And once the conversation shifts into internal norms, the public loses the only tool it has to constrain the state: the rule that the government cannot punish speech because it dislikes the viewpoint.

That is the practical danger: viewpoint suppression recast as workplace management.

To be clear, nothing in this essay requires romanticizing any police organization. Police unions and fraternal associations can say things that are irresponsible, inflammatory, or self-serving. That is not the constitutional question. The constitutional question is whether the NYPD—an arm of the municipal government—can leverage its employment power to preclude or chill independent criticism about corruption, discriminatory employment practices, or unlawful institutional behavior.

If the answer were yes, it would not stop with police organizations. It would become a blueprint: any agency could silence a class of critics by exploiting their connection to government employment. Teachers could be threatened for speaking through professional associations. Public hospital staff could be punished for speaking through medical societies. City engineers could be chilled from speaking through licensing groups. Once you accept the premise that employment status allows the state to control organizational speech, you have effectively created a government veto over civil society whenever the membership overlaps with public service.

That cannot be squared with constitutional design.

The purpose of this piece is to restore the right frame. The right frame does not start with whether a statement is “appropriate.” It starts with whether the statement is the kind of speech the state is constitutionally forbidden to suppress. And it starts with a simple but often ignored truth: the government’s power is different when it acts as an employer than when it acts as a sovereign censor. If you don’t keep that distinction clean, you will misread everything that follows—Pickering, Connick, Garcetti, Lane, and the Second Circuit’s corrections in cases like Matthews.

This essay proceeds in stages.

Section II explains the structural boundary between the government-as-employer and the government-as-sovereign, because that boundary determines whether you are even asking the right question. Later sections will show how Garcetti is frequently misapplied as a broad gag rule, why public-concern speech about policing practices sits near the core of First Amendment protection, and why corporate separateness matters when the speaker is an organization rather than an individual employee.

But the thesis can be stated now: the NYPD may manage its workforce; it may not police independent speech in civil society. And the more the state tries to control criticism about corruption or unlawful employment practices, the more obvious the First Amendment violation becomes—because that is the moment the state’s motive is most likely to be viewpoint suppression rather than operational necessity.

If we are going to talk about “who speaks for the badge,” we have to begin by insisting on the one thing institutions resist most: a limit.

II. Government as Employer vs. Government as Sovereign

Public-employee speech doctrine is often summarized in a way that makes it sound like the government gets to decide what its employees may say. That summary is wrong in both tone and content. The doctrine is not a grant of censorship authority. It is a set of narrow accommodations that recognize two truths at once: the government must be able to run a workplace, and public employees do not lose their constitutional rights at the office door.

The Supreme Court’s framework begins with the recognition that the government, when acting as an employer, has interests that are different from the government acting as a sovereign regulator of the public square. In Pickering v. Board of Education, the Court confronted a teacher fired after speaking on matters related to school funding and governance. The Court did not say, “the school district can fire employees for criticizing policy.” It created a balancing approach that asks whether the employee spoke as a citizen on a matter of public concern, and if so whether the government’s interest in efficient service outweighs the speech interest. The point is not that the government wins; the point is that the analysis exists because the government wears two hats and the Constitution treats those hats differently.

Connick v. Myers sharpened the “public concern” inquiry. The Court distinguished between speech that is essentially an internal workplace dispute and speech that meaningfully addresses issues the public has a stake in. That distinction matters because it limits the government’s ability to justify suppression based on vague claims of disruption. If the speech is truly about public concern, courts are less willing to accept “workplace harmony” as a talisman that dissolves constitutional protection.

That is the employer-side of the line.

On the other side is the government as sovereign. In that role, the government does not get to balance away speech because it is inconvenient. Viewpoint discrimination is presumptively unconstitutional. Retaliation for protected speech becomes a constitutional tort when state action is involved. The state cannot impose a general restraint on criticism simply because it believes criticism undermines confidence in an institution. In the sovereign role, the state is bound by the First Amendment’s core premise: the government cannot suppress speech to protect itself from accountability.

The doctrinal problem in police speech controversies is that agencies often try to smuggle sovereign censorship into the employer framework. They do this by redefining speech as “employment-related,” then treating that label as a trump card. But the Supreme Court has never held that any speech touching the workplace is unprotected. The question is capacity: was the speaker acting as an employee performing job duties, or as a citizen speaking on matters of public concern?

That is where Garcetti v. Ceballos enters, and also where it is frequently abused.

Garcetti held that when public employees speak pursuant to their official duties, the Constitution does not insulate that speech from employer discipline in the same way it does when they speak as citizens. This is not a general “work-related speech” exception; it is a job-duty rule. The key move is not “this is about work,” but “this is part of your assigned responsibilities.”

That distinction is crucial for policing. Police work intersects with public governance constantly. If “about policing” were enough to make speech unprotected, officers would effectively be barred from speaking as citizens about the most important issues in law enforcement—use-of-force patterns, corruption, discriminatory enforcement, quota-driven policing, and unlawful employment practices. Courts, particularly in the Second Circuit, have repeatedly had to correct that overreach by insisting that Garcetti has a boundary: job duties, not subject matter.

Lane v. Franks reinforces the point from another angle by emphasizing that truthful testimony outside one’s ordinary job duties is citizen speech even if it concerns information learned at work. The message is consistent: the government cannot convert all speech into employee speech merely because it is informed by the workplace. Government employment may supply information, perspective, and credibility; it does not erase citizenship.

Now, here is where your thought-piece becomes distinctive: once the government-as-employer line is properly drawn for individuals, it becomes even clearer for organizations.

An organization’s speech is not automatically “employee speech” because its members are employees. The government does not employ the corporation. The corporation does not have “official duties” within the agency’s job descriptions. The organization speaks through its own governance and institutional voice, not pursuant to a supervisor’s orders. So when a government employer tries to suppress organizational speech, it is often not merely misapplying Garcetti; it is trying to extend the employer framework beyond the employment relationship entirely.

That matters because the government’s justification changes when it acts against organizations. The “efficiency” rationale that sometimes carries weight in an employment context becomes far harder to sustain when the state is regulating an independent institutional actor. The state can manage the workplace. It cannot manage civil society.

At this point, it helps to name the recurring sleight of hand that causes confusion: “discipline framing.” Discipline framing is when the agency takes an act of public criticism and forces it into a workplace box—misconduct, insubordination, unbecoming conduct—so the constitutional question becomes a managerial one. The agency’s argument then becomes: “we’re not censoring speech; we’re enforcing discipline.” But in First Amendment terms, that is often just another way of saying: “we are punishing speech because of its viewpoint, but we are using employment leverage to do it.”

Courts are not blind to this maneuver. They ask whether the action is motivated by the content or viewpoint of the speech, whether the speech is on a matter of public concern, and whether the government’s asserted operational interest is real and concrete rather than speculative. Those inquiries exist precisely because the First Amendment anticipates what governments will do when criticized: claim disruption, claim morale issues, claim loss of trust—then insist those claims justify suppression.

There is, of course, a legitimate managerial sphere. Police departments can regulate on-duty communications, protect confidential investigative information, enforce rules against threats, and prevent disruptions that materially impair operations. But those are narrow, fact-specific justifications. They are not a general license to preclude criticism of corruption or unlawful employment practices.

And here is the key line for your readers: if an agency could silence speech simply by calling it “work-related,” the First Amendment would be optional for public employees. That is not the law. The whole point of Pickering, Connick, Garcetti, and Lane is to distinguish protected citizen speech from unprotected job-duty speech, and to prevent the state from using employment power as a proxy for sovereign censorship.

This is the platform on which the rest of the essay must stand. Before you argue corporate separateness, before you argue associational rights, before you argue viewpoint discrimination and retaliation, you must force the reader to see the correct frame: the NYPD is not just a supervisor; it is the state. The moment it attempts to silence independent speakers—especially on topics like corruption and unlawful employment practices—it is acting not as an employer maintaining efficiency, but as a sovereign attempting to shield itself from accountability.

That is where constitutional danger begins.

III. Matthews v. City of New York: Policing the Boundary Between Employee Speech and Public Accountability

Any serious discussion of police speech in New York that does not grapple directly with Matthews v. City of New York is incomplete. Matthews is not simply another datapoint in the long line of public-employee speech cases; it is a doctrinal correction aimed squarely at how the NYPD and similar agencies have attempted to stretch Garcetti v. Ceballos into something it was never meant to be: a general silencing rule for internal critics of policing.

To understand why Matthews matters so much for the issue of organizational speech, it is important to see the problem it was addressing. For years after Garcetti, police departments leaned heavily on a simplified proposition: if the speech “relates to work,” it is unprotected. That formulation is attractive to management because it collapses the analysis into a single step and avoids uncomfortable inquiries into motive, viewpoint, or public concern. It is also wrong.

In Matthews, the City of New York argued precisely this overbroad theory. Officer Matthews raised concerns about an arrest quota system that, in his view, distorted policing priorities and encouraged unconstitutional stops. The City responded by characterizing his speech as part of his job—after all, he was talking about policing, and he learned about quotas through his work. From the Department’s perspective, that should have ended the inquiry.

The Second Circuit refused to accept that shortcut. The court focused not on the subject matter of Matthews’s speech, but on the capacity in which he spoke. Matthews was not tasked with formulating policy, setting quotas, or advising management on arrest practices. He was not writing an internal memorandum as part of an assigned duty. He was raising concerns as a citizen about how public power was being exercised. That distinction mattered, and the court treated it as dispositive.

What Matthews makes clear is that the “official duties” inquiry under Garcetti is not a rhetorical label; it is a functional test. Speech is unprotected only when it is part of what the employee is paid to do. Policing is a public function, but not every utterance by a police officer is an act of policing. To hold otherwise would mean that police officers—precisely because they are closest to misconduct—are least able to speak about it. The Second Circuit understood that result to be incompatible with the First Amendment.

Equally important is Matthews’s treatment of public concern. The court had no difficulty concluding that criticism of arrest quotas implicated matters of public concern. That conclusion is significant because it rejects a familiar institutional move: rebranding systemic critique as a “mere workplace grievance.” Arrest quotas are not about personal job dissatisfaction; they are about how the state exercises coercive power over the public. Speech about them belongs to the citizenry, not just to management.

This matters enormously for your thought-piece, because Matthews does two things at once. First, it protects individual officers who speak out about policing practices, even when that speech arises from inside the institution. Second, and more subtly, it exposes the logical flaw in the Department’s attempt to control organizational speech. If the NYPD cannot automatically silence an individual officer who criticizes policy as a citizen, it certainly cannot claim greater authority over a separate corporate entity speaking in its own voice.

Put differently, Matthews establishes a floor. It tells us the minimum level of protection that even an individual employee enjoys when speaking on matters of public concern. Organizational speech sits above that floor, not below it. An independent corporation has no “official duties” within the NYPD. It cannot be reassigned, disciplined, or evaluated through performance reviews. The very features that made Matthews’s speech protected—citizen capacity and public concern—are even more clearly present when the speaker is an organization.

There is also an institutional lesson embedded in Matthews. The case reflects judicial skepticism toward claims that internal criticism necessarily undermines discipline or efficiency. The court did not accept abstract assertions of disruption; it demanded a real showing. That skepticism is directly relevant when agencies attempt to justify chilling organizational speech by invoking morale, unity, or public confidence. Those are the same interests, recast at a higher level of generality.

Finally, Matthews is important because it is local. This is not an abstract Supreme Court pronouncement applied at a distance. It is the Second Circuit telling the NYPD, in concrete terms, that its instinct to suppress internal dissent through expansive readings of Garcetti has limits. Your argument builds naturally on that foundation: if Matthews draws a constitutional line for individual officers, corporate separateness ensures that the line is even firmer when the speaker is an independent organization.

IV. Corporate Separateness: Why Unions and Fraternal Organizations Are Not “Employees”

The most common way people get this issue wrong is by failing to appreciate how deeply corporate separateness is embedded in American law. We treat it casually in everyday language, but legally it is one of the most consequential ideas in modern governance. A corporation is not a convenient label for a group of people; it is a distinct legal person with its own rights, obligations, and voice.

That principle applies with equal force to labor unions, fraternal organizations, professional associations, and nonprofit advocacy groups. The fact that their members share an employer does not collapse the organization into the employer’s hierarchy. The government does not employ the corporation. The corporation does not report to a precinct commander. The corporation does not have “job duties” assigned by the NYPD.

Unions illustrate this most clearly. Police unions are corporations. They bargain collectively, litigate, issue public statements, endorse or oppose policies, and openly criticize management. No one seriously argues that a police commissioner may pre-approve union press releases or discipline the union for criticizing departmental policy. That would be immediately recognized as an attempt by the employer to silence an independent institutional actor.

The same analysis applies to fraternal organizations, even if people are less accustomed to seeing it that way. These organizations are separately incorporated, governed by their own bylaws, led by officers elected by members, and funded through their own treasuries. When they speak, they speak as institutions, not as a collection of officers performing job functions. Their speech is not issued through the NYPD’s chain of command, and it does not purport to represent the Department.

Once this is understood, the constitutional implications follow almost automatically. The NYPD has no disciplinary jurisdiction over a corporation. It cannot issue lawful orders to a corporate entity. It cannot assign it duties or evaluate its performance. Any attempt to control what a corporation says is therefore not an exercise of employer authority; it is an exercise of state power directed at a private speaker.

This is where associational rights come into play. The Supreme Court has long recognized that the First Amendment protects not only individual speech, but collective expression. NAACP v. Alabama stands for the proposition that the state may not suppress or burden organizational expression simply because it dislikes the message or fears its consequences. That protection does not evaporate because the organization’s members work for the government.

Corporate speech doctrine reinforces the point. Whatever controversies surround Citizens United, one thing it makes unmistakable is that corporate form does not disqualify speech from First Amendment protection. The government cannot say, “you are a corporation, therefore you speak at our pleasure.” If that is true in the context of campaign finance, it is certainly true when the state is attempting to silence criticism of its own conduct.

This is why the “they’re cops” argument fails at a structural level. Employment status attaches to individuals, not to independent legal persons. An officer may be subject to discipline for violating workplace rules while on duty. That does not give the Department a derivative right to control the speech of every organization the officer belongs to. If it did, public employment would function as a permanent waiver of associational freedom.

The danger of ignoring corporate separateness is not hypothetical. Once agencies are permitted to collapse organizations into their membership, the chilling effect is immediate. Criticism becomes risky not because it is false or disruptive, but because it is costly. Officers learn that speaking through an organization does not insulate them; it merely paints a larger target. Over time, the line between civil society and the state erodes, and organizations that exist precisely to provide collective voice are reduced to silence.

There is also a deeper constitutional concern. Allowing a government agency to suppress organizational speech because of who belongs to the organization creates a powerful incentive for viewpoint discrimination. Agencies will tolerate friendly organizations and target hostile ones. They will describe suppression as “maintaining discipline,” but the real driver will be disagreement with the message. That is exactly the scenario the First Amendment is designed to prevent.

When you put Matthews and corporate separateness together, the picture becomes clear. Matthews tells us that even individual officers retain protected speech rights when they speak as citizens on matters of public concern. Corporate separateness tells us that independent organizations composed of officers are even further removed from the Department’s employment authority. The NYPD’s power simply does not reach that far.

This is not about granting special privileges to police organizations. It is about insisting that the state respect the same constitutional boundaries here that apply everywhere else. A government employer may manage its workforce. It may not silence civil society. And when the state is tempted to do so—especially in response to criticism about corruption or unlawful employment practices—that is precisely when courts and the public must be most vigilant.

If you’re ready, the next sections can build on this foundation by addressing viewpoint discrimination and retaliation directly, and by explaining why attempts to chill organizational speech through indirect pressure are constitutionally indistinguishable from outright censorship.

V. Viewpoint Discrimination, Retaliation, and the Illusion of “Neutral Discipline”

Once the analysis reaches this point, the constitutional problem should be unmistakable. If an independent organization speaks on matters of public concern, and the NYPD attempts to suppress or chill that speech, the Department is no longer operating in the realm of neutral workplace regulation. It is engaging in viewpoint discrimination. And viewpoint discrimination is not a technical violation—it is the most disfavored form of speech regulation in First Amendment law.

Viewpoint discrimination occurs when the government targets speech not because of how it is delivered, but because of what it says or the position it takes. The Supreme Court has been explicit: when the state punishes or suppresses speech because it disagrees with the speaker’s message, the action is presumptively unconstitutional. The reason is structural. A government that can silence criticism of itself is a government that has escaped democratic constraint.

In the policing context, viewpoint discrimination rarely announces itself openly. Agencies do not typically say, “we are suppressing this speech because it accuses us of corruption.” Instead, they adopt a set of euphemisms—discipline, professionalism, decorum, unity, morale. The vocabulary sounds neutral, managerial, even benign. But neutrality is not determined by labels. It is determined by motive and effect.

This is where courts look past formal justifications and ask what is actually happening. Is the speech being punished because it disrupts operations in a concrete, demonstrable way? Or is it being punished because it embarrasses leadership, undermines public confidence, or exposes unlawful practices? The latter justifications are not constitutionally permissible, no matter how carefully they are dressed up.

Cases like Perry v. Sindermann and O’Hare Truck Service v. City of Northlake are instructive here because they make clear that the government may not retaliate against speech indirectly. In Perry, the Court held that the absence of a formal entitlement does not give the state license to penalize protected expression. In O’Hare, the Court extended that principle to situations where retaliation takes the form of lost opportunities rather than explicit punishment. The lesson is simple: the First Amendment forbids retaliation, not just censorship.

This principle is especially important when dealing with organizational speech, because suppression often occurs by proxy. Rather than attempting to sanction the organization directly—which would make the constitutional problem obvious—the agency applies pressure to individual members. Promotions stall. Assignments change. Evaluations sour. Disciplinary scrutiny intensifies. The message is clear even if it is never written down: association has consequences.

From a constitutional perspective, this distinction is meaningless. The Supreme Court made this explicit in Heffernan v. City of Paterson, where it held that adverse action based on perceived engagement in protected political activity violates the First Amendment even if the perception is mistaken. What matters is the government’s motive. If the state acts because it believes someone is aligned with a disfavored viewpoint, the constitutional injury is complete.

Applied here, the principle is straightforward. If the NYPD targets officers because they are associated with a fraternal organization that criticizes departmental corruption or unlawful employment practices, the retaliation is no less unconstitutional than if the Department had censored the organization directly. The Constitution does not permit the state to do indirectly what it cannot do openly.

There is an additional layer to the problem when the speech concerns corruption or discrimination. Courts have repeatedly recognized that speech exposing abuse of public power lies at the heart of the First Amendment. When the government retaliates against that speech, the inference of viewpoint discrimination is particularly strong, because the government’s interest in suppressing criticism is at its apex precisely when the criticism is most damaging.

This is why abstract claims of “loss of trust” or “harm to morale” carry little weight in these cases. If such claims were sufficient, the government could always justify suppressing whistleblowers. Every disclosure of misconduct undermines someone’s trust. Every allegation of discrimination affects morale somewhere. The Constitution does not permit the government to convert those predictable consequences into a veto over speech.

The illusion of neutral discipline collapses once motive is examined. When the trigger for enforcement is criticism, when similarly situated speakers are treated differently based on message, or when discipline tracks public embarrassment rather than operational disruption, viewpoint discrimination is the only plausible explanation. At that point, the First Amendment violation is not close.

VI. Association as a Target: Why Chilling Organizational Speech Is Constitutionally Indistinguishable from Censorship

At its core, the NYPD’s attempt to control organizational speech rests on a deeper constitutional mistake: the failure to recognize that freedom of speech and freedom of association are inseparable. The First Amendment does not protect only isolated speakers standing alone. It protects the ability of individuals to band together, amplify their voices, and speak collectively—especially when confronting powerful institutions.

The Supreme Court recognized this reality long before modern public-employee speech doctrine developed. In NAACP v. Alabama, the Court held that state action burdening association can be just as constitutionally offensive as direct censorship. The case is often remembered for its protection of membership anonymity, but its deeper principle is broader: the state may not use its power to deter collective expression by making association costly or dangerous.

That principle applies with particular force when the association exists to criticize the state itself. Collective speech is often the only way individuals can safely and effectively challenge institutional misconduct. This is especially true in hierarchical organizations like police departments, where individual dissent carries professional risk. Fraternal organizations and unions exist, in part, to diffuse that risk by providing collective voice.

When the NYPD attempts to chill organizational speech—whether through direct warnings, informal pressure, or retaliatory action against members—it attacks that collective function. The harm is not limited to the individuals who experience retaliation. The harm is systemic. Other officers observe the consequences and learn the lesson: silence is safer than association.

From a constitutional standpoint, this chilling effect is not incidental. It is the injury. The First Amendment is violated not only when speech is punished, but when the state creates conditions that deter speech before it occurs. Courts have long recognized that chilling effects are particularly pernicious when the speaker is criticizing government conduct, because fear suppresses information the public has a right to hear.

This is why the government’s insistence that “we did not discipline the organization, only individuals” fails as a defense. Association is itself protected activity. Retaliating against individuals for their association with a speaking organization is no different, constitutionally, from retaliating against the organization directly. In both cases, the state is using its power to suppress a viewpoint by targeting the mechanisms through which that viewpoint is expressed.

There is also a structural danger in allowing the state to police association in this way. If government employers may punish employees for belonging to organizations that criticize policy, then civil society becomes contingent on government approval. Organizations that flatter authority flourish; organizations that challenge it wither. That is not a free marketplace of ideas. It is a managed one.

This danger is amplified in the policing context because of the asymmetry of power. The NYPD controls assignments, evaluations, promotions, and disciplinary processes. Even subtle signals of disfavor can have significant career consequences. When that power is used—explicitly or implicitly—to discourage association with critical organizations, the imbalance becomes constitutionally intolerable.

The law does not require proof of an express gag order to recognize this harm. Patterns matter. Timing matters. Disparate treatment matters. When criticism is followed by adverse action, and when association becomes a predictor of professional risk, courts are entitled to draw inferences about motive. The First Amendment does not demand naivete.

Taken together, Sections V and VI complete the arc that began earlier in this essay. If Matthews establishes that individual officers retain speech rights when criticizing policing practices, and if corporate separateness establishes that organizations are not subject to employment control, then viewpoint discrimination and retaliatory chilling explain how agencies attempt to evade those limits in practice. The techniques vary, but the objective is consistent: suppress criticism without calling it censorship.

The Constitution sees through that strategy. It treats retaliation as suppression, chilling as coercion, and association as speech. And it insists on a simple rule that institutions often resist: the state may govern, but it may not silence those who challenge how it governs.

If you want, the next sections can address the “what the NYPD can regulate” question in detail and then close with institutional implications and litigation consequences, maintaining this same level of depth and rigor.

VII. What the NYPD Can Regulate — and Why Those Powers Are Narrow by Design

Up to this point, the analysis has focused on what the NYPD cannot do: it cannot suppress independent organizational speech, it cannot retaliate against association, and it cannot disguise viewpoint discrimination as discipline. But a serious thought-piece also has to confront the other side of the equation. The NYPD does have regulatory authority. The mistake is not recognizing that authority exists; the mistake is inflating it beyond its constitutional limits.

The First Amendment does not disable government employers. It constrains them. Understanding the scope of permissible regulation is essential, because agencies routinely justify overreach by pointing to real—but limited—powers and treating them as universal.

At the most basic level, the NYPD may regulate on-duty conduct. Officers can be required to follow orders, adhere to operational protocols, maintain radio discipline, and comply with use-of-force policies. None of this raises First Amendment concerns because it does not regulate speech as speech; it regulates conduct within the performance of official duties. When an officer is acting as an agent of the state, the state may dictate how that agency relationship functions.

Closely related is the authority to regulate speech made pursuant to official duties. This is the narrow holding of Garcetti v. Ceballos. When an officer speaks because the job requires it—writing reports, giving testimony as part of assigned duties, communicating internally in the chain of command—the speech is treated as government speech or employee performance, not citizen expression. In that limited context, the First Amendment does not insulate the speaker from discipline.

The critical point, often ignored, is that this category is defined by function, not by topic. Speech is unprotected under Garcetti because it is part of what the employee is paid to do, not because it is about work. Courts have repeatedly rejected attempts to expand this category to cover all speech informed by professional experience. If subject matter alone were enough, public employees would be uniquely silenced on the very issues they know best.

The NYPD also retains authority to enforce content-neutral time, place, and manner restrictions, so long as those restrictions are genuinely neutral and narrowly tailored. For example, the Department may prohibit officers from holding press conferences while on duty, in uniform, or on Department property without authorization. It may restrict the use of official insignia to prevent false attribution. These rules are permissible because they regulate how and when speech occurs, not what is said.

Finally, the Department may regulate speech that materially interferes with operations, but this authority is often misunderstood and overstated. Courts require more than speculative claims about morale or trust. There must be a concrete showing that the speech caused, or was reasonably likely to cause, actual disruption to the functioning of the workplace. Abstract fears of embarrassment or criticism do not suffice.

This is where agencies frequently cross the constitutional line. They invoke “efficiency” as a talisman, without evidence, and treat disagreement as disruption. But the First Amendment does not allow the government to define disruption as “speech we don’t like.” If that were the rule, public-concern speech would always lose, because meaningful criticism is, by its nature, uncomfortable.

Once these narrow categories are exhausted, the NYPD’s authority ends. It does not extend to off-duty speech by independent organizations. It does not extend to commentary issued through separate corporate governance. It does not extend to public criticism of corruption, discrimination, or unlawful employment practices simply because such criticism reflects poorly on leadership.

This limitation is not an oversight. It is intentional. The Constitution draws these lines precisely because governments—especially law-enforcement agencies—have strong incentives to suppress criticism. The regulatory powers that do exist are meant to ensure operational integrity, not to insulate institutions from accountability.

Understanding what the NYPD can regulate is therefore inseparable from understanding what it cannot. The former is narrow, specific, and tied to function. The latter is broad, structural, and tied to the core purpose of the First Amendment: preventing the state from using its power to silence dissent.

VIII. Why the Confusion Persists — and Why It Is Institutionally Useful

Given how settled these principles are, a natural question follows: why does this misunderstanding persist? Why do so many people—including lawyers, commentators, and even judges—continue to blur the line between employee regulation and unconstitutional suppression of organizational speech?

The answer lies less in doctrine than in institutional incentives.

From the perspective of a powerful government agency, the ability to control narrative is enormously valuable. Public criticism threatens legitimacy, invites oversight, and creates legal exposure. Allegations of corruption or unlawful employment practices are not merely reputational nuisances; they are gateways to discovery, litigation, and structural reform. It is therefore rational, in an institutional sense, for agencies to seek ways to discourage such speech without triggering constitutional alarms.

Reframing suppression as discipline accomplishes exactly that. If criticism can be labeled “unprofessional,” “divisive,” or “harmful to morale,” the agency can invoke internal norms rather than constitutional rules. The fight moves from the First Amendment to departmental policy manuals, from courts to internal affairs. That shift is not accidental; it is strategic.

This strategy is particularly effective in hierarchical organizations like police departments, where power is asymmetric and careers are vulnerable. Officers understand, often without being told, that challenging leadership carries risk. When they see colleagues marginalized after associating with outspoken organizations, they draw their own conclusions. Silence becomes a form of self-preservation.

The confusion also persists because public-employee speech doctrine is often taught and discussed in shorthand. Garcetti becomes “employees can’t criticize their employer.” Pickering becomes “balancing test.” Nuance is lost. Capacity, function, and public concern collapse into vague impressions. That doctrinal flattening makes it easier for agencies to overclaim authority and harder for observers to spot the overreach.

There is another reason the confusion endures: it benefits not only agencies, but sometimes courts. Treating disputes as internal employment matters allows courts to avoid confronting uncomfortable questions about state power and accountability. Early dismissal becomes easier when claims are framed as personnel issues rather than constitutional conflicts. Deference replaces scrutiny.

But this avoidance has consequences. When courts accept discipline framing uncritically, they reinforce the very dynamics the First Amendment is meant to counteract. They teach agencies that suppression works if it is subtle enough. They teach employees that constitutional rights are theoretical. And they teach the public that criticism of government institutions is a privilege, not a right.

In the context of organizational speech, the cost is especially high. Civil society depends on institutions that can aggregate voices, share risk, and speak collectively. If government employers can chill those institutions whenever membership overlaps with public service, the result is a hollowed-out public sphere. The most informed critics—the people inside the system—are effectively neutralized.

This is why the confusion is not benign. It is not merely a misunderstanding to be corrected in law-review footnotes. It is a functional doctrine of control that operates through ambiguity. The more unclear the boundaries are, the easier it is for power to flow in one direction.

Clarifying these boundaries, then, is not pedantry. It is accountability work. It forces agencies to justify restrictions openly, under the correct constitutional standards. It forces courts to confront motive and effect rather than accept managerial rhetoric at face value. And it reminds the public that the First Amendment is not a courtesy extended by institutions, but a limit imposed on them.

By the time this essay reaches its conclusion, the through-line should be unmistakable. The NYPD’s authority is real, but it is bounded. It may manage employees; it may not manage truth. It may regulate conduct; it may not regulate dissent. And when independent organizations speak about corruption or unlawful employment practices, the persistence of confusion about these limits is not an accident—it is a warning sign.

IX. Litigation Consequences: How Misframing Speech Claims Warps Accountability

By the time disputes over organizational speech reach litigation, the damage caused by misframing is often already done. Complaints are dismissed early, discovery is curtailed, and constitutional claims are reduced to “personnel matters” long before courts ever confront the actual exercise of state power. This is not because the First Amendment is unclear. It is because the frame has been set incorrectly from the outset.

When organizational speech is treated as employee speech, courts are invited—sometimes subtly, sometimes explicitly—to analyze the case under the narrowest possible doctrine. Instead of asking whether the state has engaged in viewpoint discrimination against a private speaker, the court is encouraged to ask whether an employer reasonably disciplined an employee. That shift alone can determine the outcome of a case.

This is why framing is not a stylistic choice; it is outcome determinative.

In properly framed cases, the analysis begins with state action directed at an independent speaker. The questions are constitutional and structural: Was the speech on a matter of public concern? Was the government motivated by disagreement with the message? Was there retaliation or chilling effect? Was the action attributable to official policy or custom? These inquiries open the door to discovery, motive analysis, and Monell liability.

In misframed cases, those questions never get asked. Instead, the court evaluates whether internal rules were violated, whether discipline was justified, and whether disruption was alleged. The First Amendment becomes background noise. Accountability evaporates.

This is particularly dangerous in the context of policing because of the asymmetry of information. Allegations of corruption, discriminatory employment practices, or retaliatory discipline often cannot be proven without discovery. If courts allow agencies to suppress organizational speech under the guise of internal discipline, they effectively grant the state a pre-discovery veto over claims that challenge institutional misconduct.

The consequences ripple outward.

First, retaliation becomes easier. Agencies learn that they can chill criticism without formal gag orders, so long as they apply pressure indirectly. Promotions can be delayed. Assignments can be reassessed. Evaluations can quietly sour. None of these actions, standing alone, may look dramatic. Together, they create a powerful deterrent against association and speech.

Second, Monell accountability is undermined. Organizational suppression rarely happens by accident. It is typically the product of informal norms, leadership signals, and repeated practices. When courts dismiss these cases as isolated employment disputes, they obscure the systemic nature of the conduct. Patterns disappear into anecdotes. Policies hide behind discretion.

Third, civil society loses a critical source of information. Police-affiliated organizations—precisely because of their proximity to power—are often the first to identify institutional problems. When those organizations are silenced or chilled, the public hears less, not more, about how policing actually operates. Transparency suffers not because there is nothing to see, but because the speakers with the most knowledge are muted.

From a litigation perspective, the lesson is clear: claims involving suppression of organizational speech must be pleaded and argued as First Amendment violations by a government actor against independent speakers, not as garden-variety employment disputes. The capacity of the speaker, the corporate separateness of the organization, and the public-concern nature of the speech are not peripheral details; they are the core of the case.

When that framing is done correctly, the law is not hostile to accountability. Courts have tools to address viewpoint discrimination, retaliation, and chilling effects. What they lack—too often—is a clean presentation of the constitutional boundary that has been crossed.

X. Conclusion: Authority Ends Where Accountability Begins

The through-line of this essay is not complicated, but it is often resisted: government power has limits, and those limits do not dissolve simply because the government finds criticism inconvenient or threatening.

The NYPD is entitled to manage its workforce. It is entitled to regulate on-duty conduct, enforce operational rules, and maintain functional discipline. None of that is controversial. What is controversial—and unconstitutional—is the attempt to extend those powers beyond the employment relationship and into the realm of independent speech by civil society organizations.

When fraternal organizations, unions, or other police-affiliated corporations speak about corruption or unlawful employment practices, they are not engaging in insubordination. They are engaging in public accountability. They are doing exactly what the First Amendment exists to protect: criticizing the exercise of state power so that the public can judge it.

The temptation for institutions to suppress that speech is understandable. Criticism invites scrutiny. Scrutiny invites reform. Reform redistributes power. But the Constitution was written with that temptation in mind. It assumes that those who wield power will prefer silence to dissent, and it erects barriers to prevent that preference from becoming policy.

The confusion this essay addresses—between employee speech and organizational speech, between management and censorship, between discipline and retaliation—is not merely a technical mistake. It is a pressure point. It is where institutional incentives collide with constitutional limits. The more important the criticism, the greater the incentive to blur the line.

Clarity, therefore, is itself a form of accountability.

Once the distinctions are restored, the analysis becomes straightforward. Independent organizations are not employees. Their speech is not job performance. Suppressing that speech is not management; it is state action directed at a private speaker. When the suppression is motivated by disagreement with the message, it is viewpoint discrimination. When it is enforced through pressure on members, it is retaliation by proxy. When it chills association, it violates the First Amendment’s core protections.

None of this depends on sympathy for the speaker. The First Amendment does not protect speech because it is virtuous. It protects speech because unchecked power is dangerous.

If the NYPD could silence independent organizations whenever their members overlap with public employment, the principle would not stop at policing. It would become a general doctrine of control: speak carefully, associate quietly, or risk your livelihood. That is not democratic governance. It is managed dissent.

The Constitution draws a different line. It allows the state to govern, but not to insulate itself from criticism. It allows agencies to function, but not to silence civil society. And it insists on a rule that is simple, even if institutions find it inconvenient: authority ends where accountability begins.

That rule is not anti-police. It is pro-constitutional. And in a system committed to the rule of law, that distinction matters more than comfort, optics, or control.

Reader Supplement

To support this analysis, I have added two companion resources below.

First, a Slide Deck that distills the core legal framework, case law, and institutional patterns discussed in this piece. It is designed for readers who prefer a structured, visual walkthrough of the argument and for those who wish to reference or share the material in presentations or discussion.

Second, a Deep-Dive Podcast that expands on the analysis in conversational form. The podcast explores the historical context, legal doctrine, and real-world consequences in greater depth, including areas that benefit from narrative explanation rather than footnotes.

These materials are intended to supplement—not replace—the written analysis. Each offers a different way to engage with the same underlying record, depending on how you prefer to read, listen, or review complex legal issues.

Related