Executive Summary

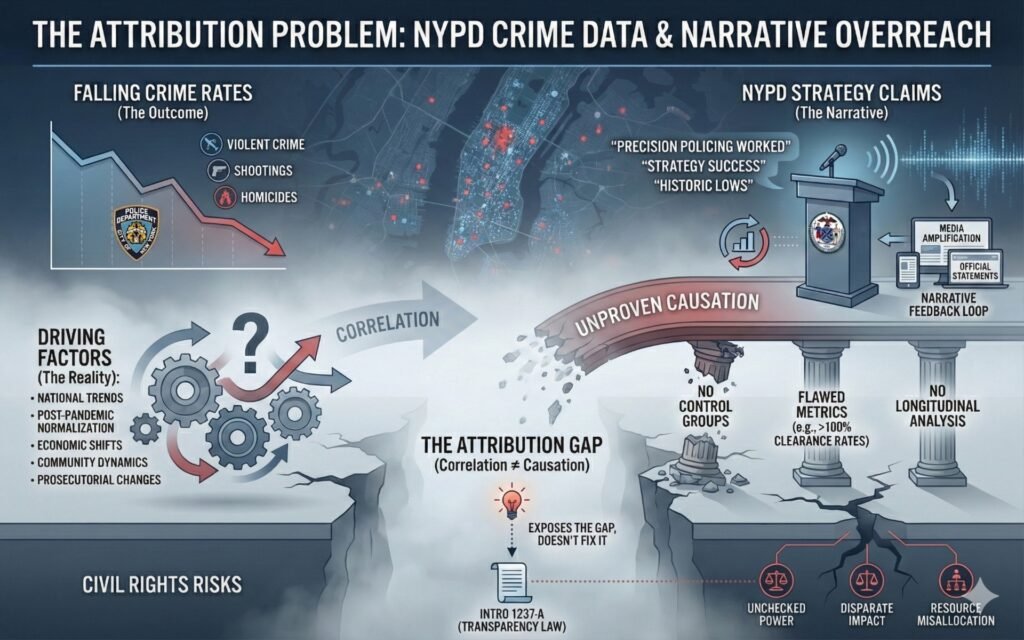

Crime has declined across the United States and in New York City in the post-pandemic period. That empirical fact is not in serious dispute. What is in dispute—and what this essay squarely confronts—is how those declines have been explained, credited, and politically deployed. The central thesis of this piece is that the New York City Police Department, assisted by legacy media institutions, has converted correlation into causation—asserting the success of specific “crime strategies” without short-term or longitudinal evidence capable of sustaining that claim.

That narrative now collides with the City’s own legislative record. In December 2025, the New York City Council released a formal analysis of NYPD clearance-rate reporting practices in connection with the passage of Introduction 1237-A, a bill requiring comprehensive, incident-level disclosure of crime and arrest data. The Council’s findings were stark: NYPD’s existing practices omitted entire categories of crime, excluded demographic and geographic detail, and historically calculated clearance rates in ways that inflated apparent performance—at times producing rates exceeding 100 percent. Those deficiencies were not cosmetic. They materially impaired transparency, accountability, and the City’s ability to evaluate what policing policies actually work.

National data published by the Federal Bureau of Investigation further underscore the problem. FBI figures show broad crime reductions across jurisdictions with radically different policing models, leadership structures, and enforcement philosophies. New York City’s experience fits squarely within that national pattern. Yet NYPD leadership and media coverage have repeatedly framed local declines as proof of departmental strategy, competence, or tactical innovation—without control groups, without multi-year analysis, and without independent evaluation. Effectiveness has been asserted, not demonstrated.

The key finding developed throughout this essay is straightforward: neither the NYPD nor the legacy media can demonstrate that the Department’s touted strategies caused the observed reductions in crime, as opposed to broader structural, demographic, and national forces such as post-pandemic normalization, economic shifts, prosecutorial practices, or nationwide trend effects. Short-term drops are treated as validation; alignment with national declines is ignored; and the methodological limits of NYPD data—now formally identified by the City Council—are left unexplained.

This failure is not merely analytical. It is institutional. When a powerful public agency claims success without proof, and when those claims are repeated uncritically despite legislative findings documenting flawed data practices, the result is a closed feedback loop that insulates policy from scrutiny. Clearance-rate inflation, selective metrics, and press-release policing do not simply misinform the public; they shape resource allocation, justify enforcement intensity, and foreclose democratic debate about what actually makes communities safer.

Accordingly, this essay frames crime-data manipulation not as a public-relations problem, but as a governance and civil-rights failure. In a system where policing authority is justified through numbers, the integrity of those numbers is inseparable from constitutional accountability. Public safety cannot be meaningfully evaluated—let alone equitably administered—when correlation is sold as causation and when the City’s own legislative findings are treated as background noise rather than a warning.

I. Crime Is Falling—But Attribution Is the Real Question

Crime has declined in the United States over the last several years, and New York City is no exception. Nationally, data reported by the Federal Bureau of Investigation reflect sustained reductions in violent crime across multiple categories, continuing a post-pandemic normalization trend observed in jurisdictions with widely divergent policing models, political leadership, and enforcement priorities. Locally, New York City has experienced parallel declines in major index crimes, including homicides and shootings, trends that have been widely reported and frequently characterized as evidence of renewed public safety.

At the level of description, these facts are uncontested. Crime, measured by standard indicators, has gone down. The more difficult—and far more consequential—question is why. That question is often skipped entirely in public discourse, replaced by a reflexive assumption that local policing strategies deserve primary credit for local outcomes. This assumption is analytically convenient, politically useful, and methodologically unsound.

The central analytical problem this essay addresses is not whether crime declined, but who gets credit for that decline—and on what evidence. When a city experiences falling crime during a period in which crime is also falling nationally, attribution cannot be presumed. The existence of a positive outcome does not, by itself, establish the cause of that outcome. Yet public commentary, official statements, and media reporting routinely collapse this distinction, treating temporal overlap as proof of effectiveness.

This conflation reflects a basic failure to distinguish between descriptive statistics and causal inference. Descriptive statistics answer a narrow question: what happened? They tell us that reported crime counts decreased over a given period. Causal inference answers a fundamentally different and far more demanding question: what produced that change? Answering the latter requires isolating variables, accounting for external forces, and testing whether the claimed intervention actually altered outcomes relative to what would have occurred in its absence.

In the context of policing, this distinction is critical. Crime rates are influenced by a complex web of factors that extend well beyond any single department’s strategies: demographic shifts, economic conditions, post-pandemic behavioral normalization, changes in prosecution and sentencing practices, social-service availability, and broader national trends all play a role. When those forces move in the same direction across the country, local declines may reflect participation in a national pattern rather than the success of a particular local initiative.

Nonetheless, public narratives in New York City have largely proceeded as if attribution were self-evident. Crime went down; therefore, the New York City Police Department must have done something right. That logic substitutes assertion for analysis. It treats correlation as causation and rewards confidence over proof. Before examining the specific strategies claimed, the metrics used to validate them, or the media narratives that amplify them, it is necessary to pause at this threshold question: what standard of evidence should be required before credit is assigned?

This section establishes that threshold. Without it, any discussion of strategy, reform, or accountability rests on an unexamined premise—that observed outcomes necessarily flow from official action. The remainder of this essay proceeds from the opposite assumption: that attribution is a claim to be proven, not a conclusion to be presumed.

II. The FBI Baseline: National Declines Without NYPD Strategies

Any serious effort to assess the effectiveness of local crime strategies must begin with an external benchmark. In the United States, that benchmark is the nationwide crime data compiled and published by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Whatever their limitations, these data sets serve a critical analytical function: they allow observers to determine whether changes in a single jurisdiction are exceptional or simply reflective of broader national movement.

Recent FBI data show sustained declines in violent crime across the country, including reductions in homicide and other serious offenses, extending beyond a single city, administration, or policing philosophy. These declines appear in jurisdictions with markedly different enforcement models—large urban departments, smaller municipal agencies, reform-oriented cities, and traditional “tough on crime” jurisdictions alike. The commonality of the trend is the point. When crime moves in the same direction across heterogeneous systems, claims of uniquely local causation require far more than temporal coincidence.

This national baseline substantially undercuts the narrative of singular local success. If New York City were experiencing crime reductions while peer cities or the nation as a whole were trending upward or remaining flat, the argument for local strategy effectiveness would at least be plausible. That is not the current landscape. Instead, New York City’s declines track closely with national patterns, suggesting participation in a widespread post-pandemic normalization rather than the demonstrable impact of any specific NYPD initiative.

The analytical consequence is straightforward: alignment with a national trend is not proof of local effectiveness. At most, it establishes that New York City did not diverge from the broader trajectory. Yet public discourse routinely treats this alignment as validation—crediting NYPD leadership and strategy for outcomes that occurred contemporaneously across the country, including in places where NYPD policies had no conceivable influence.

This is where counterfactual analysis becomes indispensable. The relevant question is not whether crime declined after certain NYPD strategies were announced or implemented, but whether crime declined more than it otherwise would have absent those strategies. That counterfactual—what would have happened in New York City if NYPD had done nothing different while national forces continued to operate—is almost never addressed. Without it, claims of causation rest on assumption rather than evidence.

Establishing a counterfactual requires comparison: to prior periods, to peer jurisdictions, or to control groups unaffected by the intervention. It also requires time. Short-term fluctuations tell us little about whether an intervention altered the underlying trajectory or merely coincided with it. In the absence of such analysis, national crime declines function as an uncontrolled variable—one that overwhelms any attempt to isolate the effect of local strategy.

The key point, therefore, is not that NYPD strategies played no role, but that their role has not been demonstrated. When the same decline occurs everywhere, assertions of unique local success demand extraordinary proof. That proof has not been offered. Instead, the national baseline has been quietly ignored, allowing correlation to masquerade as causation and narrative to substitute for analysis.